The Plight of German Missions in Mandate Cameroon: an Historical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE MISSIONARY SPIRIT in the AUGUSTANA CHURCH the American Church Is Made up of Many Varied Groups, Depending on Origin, Divisions, Changing Relationships

Augustana College Augustana Digital Commons Augustana Historical Society Publications Augustana Historical Society 1984 The iM ssionary Spirit in the Augustana Church George F. Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/ahsbooks Part of the History Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation "The iM ssionary Spirit in the Augustana Church" (1984). Augustana Historical Society Publications. https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/ahsbooks/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Augustana Historical Society at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Augustana Historical Society Publications by an authorized administrator of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Missionary Sphit in the Augustana Church George F. Hall \ THE MISSIONARY SPIRIT IN THE AUGUSTANA CHURCH The American church is made up of many varied groups, depending on origin, divisions, changing relationships. One of these was the Augustana Lutheran Church, founded by Swedish Lutheran immigrants and maintain ing an independent existence from 1860 to 1962 when it became a part of a larger Lutheran community, the Lutheran Church of America. The character of the Augustana Church can be studied from different viewpoints. In this volume Dr. George Hall describes it as a missionary church. It was born out of a missionary concern in Sweden for the thousands who had emigrated. As soon as it was formed it began to widen its field. Then its representatives were found in In dia, Puerto Rico, in China. The horizons grew to include Africa and Southwest Asia. Two World Wars created havoc, but also national and international agencies. -

Journeys and Encounters Religion, Society and the Basel Mission In

Documents on the Basel Mission in North Karnataka, Page 5. 1 Missions-Magazin 1846-1849: Translations P. & J.M. Jenkins, October 2007, revised July 2013 Journeys and Encounters Religion, Society and the Basel Mission in Northern Karnataka 1837-1852 Section Five: 1845-1849 General Survey, mission among the "Canarese and in Tulu-Land" 1846 pp. 5.2-4 BM Annual Report [1845-] 1846 pp.5.4-17 Frontispiece & key: Betgeri mission station in its landscape pp.5.16-17 BM Annual Report [1846-] 1847 pp. 5.18-34 Frontispiece & key: Malasamudra mission station in its landscape p.25 Appx. C Gottlob Wirth in the Highlands of Karnataka pp. 5.26-34 BM Annual Report [1847-] 1848 pp. 5.34-44 BM Annual Report [1848-] 1849 pp. 5.45-51 Documents on the Basel Mission in North Karnataka, Page 5. 2 Missions-Magazin 1846-1849: Translations P. & J.M. Jenkins, October 2007, revised July 2013 Mission among the Canarese and in Tulu-Land1 [This was one of the long essays that the Magazin für die neueste Geschichte published in the 1840s about the progress of all the protestant missions working in different parts of India (part of the Magazin's campaign to inform its readers about mission everywhere.2 In 1846 the third quarterly number was devoted to the area that is now Karnataka. The following summarises some of the information relevant to Northern Karnataka and the Basel Mission (sometimes referred to as the German Mission). Quotations are marked with inverted commas.] [The author of the essay is not named, and the report does not usually specify from which missionary society the named missionaries came. -

Were German Colonies Profitable?

Were German colonies profitable? Marco Cokić BSc Economics 3rd year University College London Explore Econ Undergraduate Research Conference February 2020 Introduction In the era of colonialization, several, mainly European, powers tried to conquer areas very far away from their mainland, thereby creating multicontinental empires. One of these European powers was the German Empire which entered the game for colonies in the 1880s and was forced to leave it after World War I. Still, these involvements had a significant impact on several aspects of the German Empire. This essay discusses the question if the colonial policy of the German Empire until 1914 was an economic success. The reason for this approach is twofold. Firstly, economics can be seen as one of the main motivations of colonial policy (Blackbourn, 2003). Hence, looking at the economic results of this undertaking as a measure of success seems reasonable. Secondly, economic development can be measured relatively accurately and is a good proxy for defining success of the German colonial policy. Therefore, economic data will be used and tested against the economic hopes of advocates of colonialism during that period. The essay is split up into three main parts. In the first part, the historical background behind German colonialization and the colonies is introduced. After a brief explanation of the empirical strategy for this paper, data will be used to show if the German hopes were fulfilled. Theoretical background The German economy of the 1880s and German aims in the colonies In the 1880s, Germany was an economic leader. Several branches such as the chemical industry were worldwide leaders in their sectors and economic growth was, compared to other countries, very high (Tilly, 2010). -

Faith-Based Organizations in Development Discourses And

2 From missionaries to ecumenical co-workers A case study from Mission 21 in Kalimantan, Indonesia Claudia Hoffmann Introduction Mission 21, based in Basel, Switzerland, emerged through the union of several missionary organisations – Basel Mission is the best known amongst them – and was officially founded on 1 January 2001. Mission 21 sees its key tasks today in reduction of poverty, health care, agriculture, fair trade, education, the advance ment of peace, the empowerment of women and gender equality. Coincidentally, the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were formulated around the same time, in September 2000, at the United Nations headquarters in New York by world leaders, “committing their nations to a new global partnership to reduce extreme poverty and setting out a series of time-bound targets” (United Nations 2016). The aims and goals of Mission 21 are therefore very similar to the agenda of secular development agencies trying to achieve the MDGs. Despite this simi larity to secular development organisations, Mission 21 is very keen to show the continuity between their work nowadays and their initial history in the early 19th century. Although there have been several considerable frictions, particularly dur ing the second half of the 20th century, their profile did not substantially change. This mission organisation had to come across with changes, not only recently in the early 2000s, but also during the 1950s and in the 1960s Basel Mission had to deal with several frictions that affected their work and self-concept. This interesting time of transition to post-colonialism constitutes an underestimated period in the history of Christianity in the 20th century. -

Basel German Evangelical Mission

THE SIXTY-FIRST REPORT OF TH E BASEL GERMAN EVANGELICAL MISSION IN SOUTH-WESTERN INDIA FOR THE YEAR 1900 MANGALORE PRINTED AT THE BASEL MISSION PRESS 1901 European missionaries o f tixe B a s e l G-erias-aaa. ZO-^ra-ia-g-elical S cission .. Corrected up to the ist May 1 901. [The letter (m) after the names signifies “married”, and the letter (w) “widower”. The names of unordained missionaries are marked with an asterisk.] N ative D ate of Name A ctiv e Station. Country Service 1. W. Stokes (m) India 1860 Kaity (Coonoor) 2. S. Walter (m) Switzerland 1865 Vaniyankulamlj B. G. Ritter (m) Germany 1869 Mulki (S. Cañara) 4. J. A. Brasehe (m) do. 1869 Udipi do. 5. W. Sikemeier (m) Holland 1870 Mercara (Coorg) 6. J. Hermelink (m) Germany 1872 Mangalore 7. G. Grossmann (m) Switzerland 1874 Kotagiri (Nilgiri) 8. J. Baumann (m)* do. 1874 Mangalore 9. W. Lütze (m) Germany 1875 Kaity (Niigiri) 10. J. B. Veil (m)* do. 1875 Mercara (Coorg) : 11. L. J. Frohnmeyer (m) do. 1876 Tellicherry (Nettur) 12. J. G. Kiihnle (m) do. 1878 Palghat 13. H. Altenmüller (m)* do. 1878 Mangalore 14. C. D. Warth (m) do. 1878 Bettigeri 15. Chr. Keppler (m) do. 1879 Udipi 16. J. J. Jaus (m) do. 1879 Calicut 17. F. Stierlin (m)* do. 1880 Mangalore 18. K. Ernst (m) do. 1881 Dharwar 19. F. Eisfelder (m) do. 1882 Summadi-Guledgudd 20. M. Schaible (m) do. 1883 Mangalore 21. B. Liithi (m) Switzerland 1884 do. 22. K. Hole (m) Germany 1884 Cannanore 23. -

The Impact of Basel Mission Ideology on the Thought of Carl Christian Reindorf Heinz Hauser-Renner

“Obstinate” Pastor and Pioneer Historian: The Impact of Basel Mission Ideology on the Thought of Carl Christian Reindorf Heinz Hauser-Renner n 1895, after twenty-five years of historical and ethnological Reindorf’s Western Education Iresearch, Carl Christian Reindorf, a Ghanaian pastor of the Basel Mission, produced a massive and systematic work about Reindorf’s Western education consisted of five years’ attendance the people of modern southern Ghana, The History of the Gold at the Danish castle school at Fort Christiansborg (1842–47), close Coast and Asante (1895).1 Reindorf, “the first African to publish to Osu in the greater Accra area, and another six years’ training at a full-length Western-style history of a region of Africa,”2 was the newly founded Basel Mission school at Osu (1847–55), minus a born in 1834 at Prampram/Gbugblã, Ghana, and he died in 1917 two-year break working as a trader for one of his uncles (1850–52). at Osu, Ghana.3 He was in the service of the Basel Mission as a At the Danish castle school Reindorf was taught the catechism and catechist and teacher, and later as a pastor until his retirement in arithmetic in Danish. Basel missionary Elias Schrenk later noted 1893; but he was also known as an herbalist, farmer, and medi- that the boys did not understand much Danish and therefore did cal officer as well as an intellectual and a pioneer historian. The not learn much, and he also observed that Christian principles intellectual history of the Gold Coast, like that of much of Africa, were not strictly followed, as the children were even allowed to is yet to be thoroughly studied. -

Mohr on Grant, 'Healing and Power in Ghana: Early Indigenous Expressions of Christianity'

H-Africa Mohr on Grant, 'Healing and Power in Ghana: Early Indigenous Expressions of Christianity' Review published on Thursday, January 28, 2021 Paul Glen Grant. Healing and Power in Ghana: Early Indigenous Expressions of Christianity. Waco: Baylor University Press, 2020. 341 pp. $59.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-4813-1267-7. Reviewed by Adam H. Mohr (University of Pennsylvania) Published on H-Africa (January, 2021) Commissioned by David D. Hurlbut (Independent Scholar) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=55363 Scholars of global Christianity like Philip Jenkins inThe Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (2011) argue that a distinguishing feature of African Christianity comparative to other regional Christianities is its focus on healing. It is also an idea I have been trying to develop in my own writing about African Christianity, particularly my first book,Enchanted Calvinism: Labor Migration, Afflicting Spirits, and Christian Therapy in the Presbyterian Church of Ghana (2013) as well as my research and writing on Faith Tabernacle in West Africa. Here, for the first time, Paul Grant has examined the precolonial mission from Basel in Ghana to detail this argument in the earliest days of mission in West Africa. A strong link is made to the recent research on Pentecostalism in Ghana, where Grant argues that there are ontological and epistemological continuities between the type of Christianity established in the Akuapem hills in the nineteenth century and late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century Pentecostalism, even without institutional continuity. The point here echoes Jenkins’s observation about popular Christianity in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: Ghanaian Christianity from its earliest times was primarily about healing, protection, and power in its broad, expansive, African qualities. -

French and British Colonial Legacies in Education: a Natural Experiment in Cameroon

French and British Colonial Legacies in Education: A Natural Experiment in Cameroon Yannick Dupraz∗ 2015 most recent version: http://www.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/IMG/pdf/ jobmarket-paper-dupraz-pse.pdf Abstract. | Does colonial history matter for development? In Sub-Saharan Africa, economists have argued that the British colonial legacy was more growth-inducing than others, especially through its effect on education. This paper uses the division of German Kamerun between the British and the French after WWI as a natural experiment to identify the causal effect of colonizer identity on education. Using exhaustive geolocated census data, I estimate a border discontinuity for various cohorts over the 20th century: the British effect on education is positive for individuals of school age in the 1920s and 1930s; it quickly fades away in the late colonial period and eventually becomes negative, favoring the French side. In the most recent cohorts, I find no border discontinuity in primary education, but I do find a positive British effect in secondary school completion | likely explained by a higher rate of grade repetition in the francophone system. I also find a strong, positive British effect on the percentage of Christians for all cohorts. I argue that my results are best explained by supply factors: before WWII, the British colonial government provided incentives for missions to supply formal education and allowed local governments to open public schools, but the British effect was quickly smoothed away by an increase in French education investments in the late colonial period. Though the divergence in human capital did not persist, its effect on religion was highly persistent. -

British Southern Cameroon (Anglophone)

American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) 2021 American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) e-ISSN :2378-703X Volume-5, Issue-4, pp-555-560 www.ajhssr.com Research Paper Open Access British Southern Cameroon (Anglophone) Crisis in Cameroon and British (Western) Togoland Movement in Ghana: Comparing two Post-Independence separatist conflicts in Africa Joseph LonNfi, Christian Pagbe Musah The University of Bamenda, Cameroon ABSTRACT: The UN trust territories of British Togoland and British Southern Cameroons at independence and following UN organised plebiscites, choose to gain independence by joining the Republic of Ghana and the Republic of Cameroon in 1955 and 1961 respectively. Today, some indigenes of the two territories are protesting against the unions and are advocating separation. This study, based on secondary sources, examines the similarities and differences between the two secession movements arguing that their similar colonial history played in favour of today’s conflicts and that the violent, bloody and more advanced conflict in Cameroon is inspiring the movement in favour of an independent Western Togoland in Ghana. It reveals that colonial identities are unfortunately still very strong in Africa and may continue to obstruct political integration on the continent for a long time. Key Words: Anglophones, Cameroon, Ghana, Secession, Togolanders, I. INTRODUCTION In July1884, Germany annexed Togoland and Kamerun (Cameroon). When the First World War started in Europe, Anglo-French forces invaded Togoland and Cameroon and defeated German troops in these colonies. In 1916, Togoland was partitioned into British Togoland and French Togoland while Cameroon was also partitioned like Togoland into two unequal portions of British Cameroons and French Cameroun. -

DOCUMENT RESUME AUTHOR Salamone, Frank A., Ed. Anthropologists and Missionaries. Part II. Studies in Third World Societies. Publ

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 271 366 SO 017 295 AUTHOR Salamone, Frank A., Ed. TITLE Anthropologists and Missionaries. Part II. Studies in Third World Societies. Publication Number Twenty-Six. INSTITUTION College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA. Dept. of Anthropology. PUB DATE 85 NOTE 314p.; For part Iof this study, see SO 017 268. For other studies in this series, see ED 251 334 and SO 017 296-297. AVAILABLE FROM Studies in Third World Societies, Department of Anthropology, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA 23185 ($20.00; $35.00 set). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Anthropology; *Clergy; Cross Cultural Studies; Cultural Influences; Cultural Pluralism; Culture Conflict; Developed Nations; *Developing Nations; Ethnography; Ethnology; *Global Aoproach; Modernization; Non Western Civili%ation; Poverty; Religious Differences; Religious (:ganizations; *Sociocultural Patterns; Socioeconomic Influences; Traditionalism; World Problems IDENTIFIERS *Missionaries ABSTRACT The topics of anthropologist-missionary relationships, theology and missiology, research methods and missionary contributions to ethnology, missionary training and methods, and specific case studies are presented. The ten essays are: (1) "An Ethnoethnography of Missionaries in Kalingaland" (Robert Lawless); (2) "Missionization and Social Change in Africa: The Case of the Church of the Brethren Mission/Ekklesiyar Yan'Uwa Nigeria in Northeastern Nigeria" (Philip Kulp); (3) "The Summer Institute -

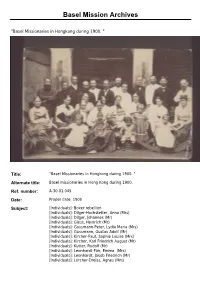

"Basel Missionaries in Hongkong During 1900. "

Basel Mission Archives "Basel Missionaries in Hongkong during 1900. " Title: "Basel Missionaries in Hongkong during 1900. " Alternate title: Basel missionaries in Hong Kong during 1900. Ref. number: A-30.01.045 Date: Proper date: 1900 Subject: [Individuals]: Boxer rebellion [Individuals]: Dilger-Hochstetter, Anna (Mrs) [Individuals]: Dilger, Johannes (Mr) [Individuals]: Giess, Heinrich (Mr) [Individuals]: Gussmann-Peter, Lydia Maria (Mrs) [Individuals]: Gussmann, Gustav Adolf (Mr) [Individuals]: Kircher-Faut, Sophie Louise (Mrs) [Individuals]: Kircher, Karl Friedrich August (Mr) [Individuals]: Kutter, Rudolf (Mr) [Individuals]: Leonhardt-Fäh, Emma (Mrs) [Individuals]: Leonhardt, Jakob Friedrich (Mr) [Individuals]: Lörcher-Dreiss, Agnes (Mrs) Basel Mission Archives [Individuals]: Lörcher, Jakob Gottlob (Mr) [Individuals]: Lutz, Samuel (Mr) [Individuals]: Ott-Walther, Wilhelmine Juliane (Mrs) [Individuals]: Ott, Rudolf (Mr) [Individuals]: Reusch-Keller, Pauline (Mrs) [Individuals]: Reusch, Christian Gottlieb (Mr) [Individuals]: Rohde, Hermann (Mr) [Individuals]: Schultze, Maria Rudolfine Agnes (child) [Individuals]: Schultze, Otto Karl Eduard (Mr) [Individuals]: Ziegler, Johann Georg (Mr) [Individuals]: Schultze-Michel, Sophie (Mrs) [Individuals]: Rohde-Kopp, Rosina Christ. (Mrs) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Dilger, Johannes (Mr) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Giess, Heinrich (Mr) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Lutz, Samuel (Mr) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Reusch, Christian Gottlieb (Mr) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Schultze, -

Encounters in Quest of Christian Womanhood Studies in Christian Mission

Encounters in Quest of Christian Womanhood Studies in Christian Mission General Editors Marc R. Spindler, Leiden University Heleen L. Murre-van den Berg, Leiden University Editorial Board Peggy Brock, Edith Cowan University James Grayson, University of Sheffield David Maxwell, Keele University VOLUME 39 Encounters in Quest of Christian Womanhood The Basel Mission in Pre- and Early Colonial Ghana By Ulrike Sill LEIDEN • BOSTON 2010 Cover illustration: Archive Mission 21/Basel Mission QD-30.016.0009 “Indigenous teachers. In the centre of the front row: Mrs Lieb.” Ghana Taken Between 1.01.1881 and 31.12.1900 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sill, Ulrike. Encounters in quest of Christian womanhood : the Basel Mission in pre- and early colonial Ghana / by Ulrike Sill. p. cm. — (Studies in Christian mission, 0924-9389 ; v. 39) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-18450-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Missions—Ghana—History—19th century. 2. Christian women—Ghana— History—19th century. 3. Evangelische Missionsgesellschaft in Basel—History—19th century. 4. Ghana—Church history—19th century. I. Title. II. Series. BV3625.G6S56 2010 266’.0234940667082—dc22 2010011777 ISSN 0924-9389 ISBN 978 90 04 18888 4 Copyright 2010 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.