Journeys and Encounters Religion, Society and the Basel Mission In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Plight of German Missions in Mandate Cameroon: an Historical Analysis

Brazilian Journal of African Studies e-ISSN 2448-3923 | ISSN 2448-3907 | v.2, n.3 | p.111-130 | Jan./Jun. 2017 THE PLIGHT OF GERMAN MISSIONS IN MANDATE CAMEROON: AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS Lang Michael Kpughe1 Introductory Background The German annexation of Cameroon in 1884 marked the beginning of the exploitation and Germanization of the territory. While the exploitative German colonial agenda was motivated by economic exigencies at home, the policy of Germanization emerged within the context of national self- image that was running its course in nineteenth-century Europe. Germany, like other colonial powers, manifested a faulty feeling of what Etim (2014: 197) describes as a “moral and racial superiority” over Africans. Bringing Africans to the same level of civilization with Europeans, according to European colonial philosophy, required that colonialism be given a civilizing perspective. This civilizing agenda, it should be noted, turned out to be a common goal for both missionaries and colonial governments. Indeed the civilization of Africans was central to governments and mission agencies. It was in this context of baseless cultural arrogance that the missionization of Africa unfolded, with funds and security offered by colonial governments. Clearly, missionaries approved and promoted the pseudo-scientific colonial goal of Europeanizing Africa through the imposition of European culture, religion and philosophy. According to Pawlikova-Vilhanova (2007: 258), Christianity provided access to a Western civilization and culture pattern which was bound to subjugate African society. There was complicity between colonial governments and missions in the cultural imperialism that coursed in Africa (Woodberry 2008; Strayer 1976). By 1884 when Germany annexed Cameroon and other territories, the exploitation and civilization of African societies had become a hallmark 1 Department of History, University of Bamenda, Bamenda, Cameroon. -

Dakshin: Vegetarian Cuisine from South India Free

FREE DAKSHIN: VEGETARIAN CUISINE FROM SOUTH INDIA PDF Chandra Padmanabhan | 176 pages | 22 Sep 1999 | Periplus Editions (Hong Kong) Ltd | 9789625935270 | English | Hong Kong, Hong Kong Dakshin : South Indian Bistro Here are some of the most delicious regional south Indian recipes you can try at home. Dosa and chutney are just a brief trailer to a colourful, rich and absolutely fascinating culinary journey that is South India. With its 5 states, 2 union territories, rocky plateau, river valleys and coastal plains, the south of India is extremely different from its Northern counterpart. But before we get into details like ingredients and cooking techniques, let's talk about some aspects that are common to those that live in the South. Firstly, most people eat with their right hand and leave the left one Dakshin: Vegetarian Cuisine from South India for drinking water. Also, licking curry off your finger does taste really good! Rice is their grain of choice and lentils and daals are equally important. Also read: Why people eat with their hands in Kerala? Sambhar is an important dish to South Indians. Photo Credit: iStock Pickles and Pappadams are always served on the side and yogurt makes a frequent appearance as well. Coconut is one of the most important ingredients and is used in various forms: dry, desiccated or as is. Some of the cooking is also done Dakshin: Vegetarian Cuisine from South India coconut oil. The South of India is known as 'the land of spices' and for all the right reasons. Cinnamon, cardamom, cumin, nutmeg, chilli, mustard, curry leaves - the list goes on. -

THE MISSIONARY SPIRIT in the AUGUSTANA CHURCH the American Church Is Made up of Many Varied Groups, Depending on Origin, Divisions, Changing Relationships

Augustana College Augustana Digital Commons Augustana Historical Society Publications Augustana Historical Society 1984 The iM ssionary Spirit in the Augustana Church George F. Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/ahsbooks Part of the History Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation "The iM ssionary Spirit in the Augustana Church" (1984). Augustana Historical Society Publications. https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/ahsbooks/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Augustana Historical Society at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Augustana Historical Society Publications by an authorized administrator of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Missionary Sphit in the Augustana Church George F. Hall \ THE MISSIONARY SPIRIT IN THE AUGUSTANA CHURCH The American church is made up of many varied groups, depending on origin, divisions, changing relationships. One of these was the Augustana Lutheran Church, founded by Swedish Lutheran immigrants and maintain ing an independent existence from 1860 to 1962 when it became a part of a larger Lutheran community, the Lutheran Church of America. The character of the Augustana Church can be studied from different viewpoints. In this volume Dr. George Hall describes it as a missionary church. It was born out of a missionary concern in Sweden for the thousands who had emigrated. As soon as it was formed it began to widen its field. Then its representatives were found in In dia, Puerto Rico, in China. The horizons grew to include Africa and Southwest Asia. Two World Wars created havoc, but also national and international agencies. -

Updated Proposal to Encode Tulu-Tigalari Script in Unicode

Updated proposal to encode Tulu-Tigalari script in Unicode Vaishnavi Murthy Kodipady Yerkadithaya [ [email protected] ] Vinodh Rajan [ [email protected] ] 04/03/2021 Document History & Background Documents : (This document replaces L2/17-378) L2/11-120R Preliminary proposal for encoding the Tulu script in the SMP of the UCS – Michael Everson L2/16-241 Preliminary proposal to encode Tigalari script – Vaishnavi Murthy K Y L2/16-342 Recommendations to UTC #149 November 2016 on Script Proposals – Deborah Anderson, Ken Whistler, Roozbeh Pournader, Andrew Glass and Laurentiu Iancu L2/17-182 Comments on encoding the Tigalari script – Srinidhi and Sridatta L2/18-175 Replies to Script Ad Hoc Recommendations (L2/16-342) and Comments (L2/17-182) on Tigalari proposal (L2/16-241) – Vaishnavi Murthy K Y L2/17-378 Preliminary proposal to encode Tigalari script – Vaishnavi Murthy K Y, Vinodh Rajan L2/17-411 Letter in support of preliminary proposal to encode Tigalari – Guru Prasad (Has withdrawn support. This letter needs to be disregarded.) L2/17-422 Letter to Vaishnavi Murthy in support of Tigalari encoding proposal – A. V. Nagasampige L2/18-039 Recommendations to UTC #154 January 2018 on Script Proposals – Deborah Anderson, Ken Whistler, Roozbeh Pournader, Lisa Moore, Liang Hai, and Richard Cook PROPOSAL TO ENCODE TIGALARI SCRIPT IN UNICODE 2 A note on recent updates : −−−Tigalari Script is renamed Tulu-Tigalari script. The reason for the same is discussed under section 1.1 (pp. 4-5) of this paper & elaborately in the supplementary paper Tulu Language and Tulu-Tigalari script (pp. 5-13). −−−This proposal attempts to harmonize the use of the Tulu-Tigalari script for Tulu, Sanskrit and Kannada languages for archival use. -

Faith-Based Organizations in Development Discourses And

2 From missionaries to ecumenical co-workers A case study from Mission 21 in Kalimantan, Indonesia Claudia Hoffmann Introduction Mission 21, based in Basel, Switzerland, emerged through the union of several missionary organisations – Basel Mission is the best known amongst them – and was officially founded on 1 January 2001. Mission 21 sees its key tasks today in reduction of poverty, health care, agriculture, fair trade, education, the advance ment of peace, the empowerment of women and gender equality. Coincidentally, the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were formulated around the same time, in September 2000, at the United Nations headquarters in New York by world leaders, “committing their nations to a new global partnership to reduce extreme poverty and setting out a series of time-bound targets” (United Nations 2016). The aims and goals of Mission 21 are therefore very similar to the agenda of secular development agencies trying to achieve the MDGs. Despite this simi larity to secular development organisations, Mission 21 is very keen to show the continuity between their work nowadays and their initial history in the early 19th century. Although there have been several considerable frictions, particularly dur ing the second half of the 20th century, their profile did not substantially change. This mission organisation had to come across with changes, not only recently in the early 2000s, but also during the 1950s and in the 1960s Basel Mission had to deal with several frictions that affected their work and self-concept. This interesting time of transition to post-colonialism constitutes an underestimated period in the history of Christianity in the 20th century. -

Basel German Evangelical Mission

THE SIXTY-FIRST REPORT OF TH E BASEL GERMAN EVANGELICAL MISSION IN SOUTH-WESTERN INDIA FOR THE YEAR 1900 MANGALORE PRINTED AT THE BASEL MISSION PRESS 1901 European missionaries o f tixe B a s e l G-erias-aaa. ZO-^ra-ia-g-elical S cission .. Corrected up to the ist May 1 901. [The letter (m) after the names signifies “married”, and the letter (w) “widower”. The names of unordained missionaries are marked with an asterisk.] N ative D ate of Name A ctiv e Station. Country Service 1. W. Stokes (m) India 1860 Kaity (Coonoor) 2. S. Walter (m) Switzerland 1865 Vaniyankulamlj B. G. Ritter (m) Germany 1869 Mulki (S. Cañara) 4. J. A. Brasehe (m) do. 1869 Udipi do. 5. W. Sikemeier (m) Holland 1870 Mercara (Coorg) 6. J. Hermelink (m) Germany 1872 Mangalore 7. G. Grossmann (m) Switzerland 1874 Kotagiri (Nilgiri) 8. J. Baumann (m)* do. 1874 Mangalore 9. W. Lütze (m) Germany 1875 Kaity (Niigiri) 10. J. B. Veil (m)* do. 1875 Mercara (Coorg) : 11. L. J. Frohnmeyer (m) do. 1876 Tellicherry (Nettur) 12. J. G. Kiihnle (m) do. 1878 Palghat 13. H. Altenmüller (m)* do. 1878 Mangalore 14. C. D. Warth (m) do. 1878 Bettigeri 15. Chr. Keppler (m) do. 1879 Udipi 16. J. J. Jaus (m) do. 1879 Calicut 17. F. Stierlin (m)* do. 1880 Mangalore 18. K. Ernst (m) do. 1881 Dharwar 19. F. Eisfelder (m) do. 1882 Summadi-Guledgudd 20. M. Schaible (m) do. 1883 Mangalore 21. B. Liithi (m) Switzerland 1884 do. 22. K. Hole (m) Germany 1884 Cannanore 23. -

The Impact of Basel Mission Ideology on the Thought of Carl Christian Reindorf Heinz Hauser-Renner

“Obstinate” Pastor and Pioneer Historian: The Impact of Basel Mission Ideology on the Thought of Carl Christian Reindorf Heinz Hauser-Renner n 1895, after twenty-five years of historical and ethnological Reindorf’s Western Education Iresearch, Carl Christian Reindorf, a Ghanaian pastor of the Basel Mission, produced a massive and systematic work about Reindorf’s Western education consisted of five years’ attendance the people of modern southern Ghana, The History of the Gold at the Danish castle school at Fort Christiansborg (1842–47), close Coast and Asante (1895).1 Reindorf, “the first African to publish to Osu in the greater Accra area, and another six years’ training at a full-length Western-style history of a region of Africa,”2 was the newly founded Basel Mission school at Osu (1847–55), minus a born in 1834 at Prampram/Gbugblã, Ghana, and he died in 1917 two-year break working as a trader for one of his uncles (1850–52). at Osu, Ghana.3 He was in the service of the Basel Mission as a At the Danish castle school Reindorf was taught the catechism and catechist and teacher, and later as a pastor until his retirement in arithmetic in Danish. Basel missionary Elias Schrenk later noted 1893; but he was also known as an herbalist, farmer, and medi- that the boys did not understand much Danish and therefore did cal officer as well as an intellectual and a pioneer historian. The not learn much, and he also observed that Christian principles intellectual history of the Gold Coast, like that of much of Africa, were not strictly followed, as the children were even allowed to is yet to be thoroughly studied. -

Mohr on Grant, 'Healing and Power in Ghana: Early Indigenous Expressions of Christianity'

H-Africa Mohr on Grant, 'Healing and Power in Ghana: Early Indigenous Expressions of Christianity' Review published on Thursday, January 28, 2021 Paul Glen Grant. Healing and Power in Ghana: Early Indigenous Expressions of Christianity. Waco: Baylor University Press, 2020. 341 pp. $59.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-4813-1267-7. Reviewed by Adam H. Mohr (University of Pennsylvania) Published on H-Africa (January, 2021) Commissioned by David D. Hurlbut (Independent Scholar) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=55363 Scholars of global Christianity like Philip Jenkins inThe Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (2011) argue that a distinguishing feature of African Christianity comparative to other regional Christianities is its focus on healing. It is also an idea I have been trying to develop in my own writing about African Christianity, particularly my first book,Enchanted Calvinism: Labor Migration, Afflicting Spirits, and Christian Therapy in the Presbyterian Church of Ghana (2013) as well as my research and writing on Faith Tabernacle in West Africa. Here, for the first time, Paul Grant has examined the precolonial mission from Basel in Ghana to detail this argument in the earliest days of mission in West Africa. A strong link is made to the recent research on Pentecostalism in Ghana, where Grant argues that there are ontological and epistemological continuities between the type of Christianity established in the Akuapem hills in the nineteenth century and late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century Pentecostalism, even without institutional continuity. The point here echoes Jenkins’s observation about popular Christianity in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: Ghanaian Christianity from its earliest times was primarily about healing, protection, and power in its broad, expansive, African qualities. -

July 2021.Pmd

MANGALORE TODAY - SEPTEMBER 2021 1 2 MANGALORE TODAY - SEPTEMBER 2021 PPPOWER POINT PICTURE OF THE MONTH Hands-on Experience! Union Minister of State for Agriculture and Farmers' Welfare Shobha Karandlaje joins farmers in cultivating a fallow land at Kadekar village in Udupi as part of Hadilu Bhoomi Revival Scheme. ““““““ WWWORDSWORTH ”””””” “We must break the walls of “The musical world has caste, religion, superstitions the immense power to as well as mistrust that attract lakhs of people as create impediments in the music plays a very key role path of our progress” in enlivening our minds Prof Sabeeha B.Gowda, Professor, Dept of and hearts” Kannada Studies of Mangalore University at noted singer Ajay Warrior at the inaurual of a farewell ceremony on the occasion of her “Knowledge of local Karavali Music Camp in Mangaluru. retirement from service. languages will go a long way in assisting the police “Ranga Mandiras need to be “Man can lead a peaceful to efficiently maintain law protected if we have to life when he incorporates and order as well as in preserve and promote the good values and shuns his investigation of crimes” theatrical field” ego” City Police Commissioner N Shashi eminent Kannada movie director Rajendra Prof. P S Yadapadittaya, Vice Chancellor of Kumar at the inaugural of the month Singh Babu while launching the fund raising Mangalore University at the Kanaka lecture long Tulu learning workshop for police drive for the renovation of Don Bosco Hall in series at the University. officers and personnel. Mangaluru. MANGALORE TODAY - SEPTEMBER 2021 3 EEEDITOR’’’SSS EDGE VOL 24 ISSUE 7 SEPTEMBER 2021 Publisher and Editor V. -

Does Medieval Political System of Tulunadu Represents Lower Feudalism…?

DOES MEDIEVAL POLITICAL SYSTEM OF TULUNADU REPRESENTS LOWER FEUDALISM…? Dr. SURESH RAI K. Associate Professor of History Historically, Tulunadu, is the undivided district of Dakshina Kannada in Karnataka and Kasaragod district in Kerala State. The nomenclature ‘Dakshina Kannada’ is used here to refer to the present Dakshina Kannada district together with Udupi district separated in 1998, which were jointly referred to as ‘South Canara’ earlier. ‘South Canara’ was an extensively used term during colonial time, and it has been retained in special circumstances and while mentioning colonial records. The name ‘Kanara’, which was formerly spelt as ‘Canara’ is derived from Kannada, the name of the regional language of the State. It appears that the Portuguese, who, on arrival in this part of India, found the common linguistic medium of the people to be Kannada, and accordingly called the area ‘Canara’; ‘d’ being not much in use in Portuguese. This name applied to the whole coastal belt of Karnataka and was continued to be used as such by the British. It is therefore necessary to deploy Tulunadu to refer to the ‘cultural zone’ that included Dakshina Kannada, Udupi, and Kasaragod districts. The present districts of Karnataka like North Canara, South Canara, Udupi and Kasaragod of Kerala were known as the Canara and Soonda Province, which was under the Madras Presidency. In 1799 AD, after the fall of Tippu Sultan, Tulunadu was brought under the new Canara province. The northern region of Canara province was called North Canara. The same names continued as North and South Kanara after the unification of Karnataka State. -

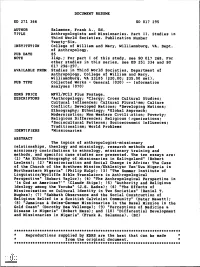

DOCUMENT RESUME AUTHOR Salamone, Frank A., Ed. Anthropologists and Missionaries. Part II. Studies in Third World Societies. Publ

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 271 366 SO 017 295 AUTHOR Salamone, Frank A., Ed. TITLE Anthropologists and Missionaries. Part II. Studies in Third World Societies. Publication Number Twenty-Six. INSTITUTION College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA. Dept. of Anthropology. PUB DATE 85 NOTE 314p.; For part Iof this study, see SO 017 268. For other studies in this series, see ED 251 334 and SO 017 296-297. AVAILABLE FROM Studies in Third World Societies, Department of Anthropology, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA 23185 ($20.00; $35.00 set). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Anthropology; *Clergy; Cross Cultural Studies; Cultural Influences; Cultural Pluralism; Culture Conflict; Developed Nations; *Developing Nations; Ethnography; Ethnology; *Global Aoproach; Modernization; Non Western Civili%ation; Poverty; Religious Differences; Religious (:ganizations; *Sociocultural Patterns; Socioeconomic Influences; Traditionalism; World Problems IDENTIFIERS *Missionaries ABSTRACT The topics of anthropologist-missionary relationships, theology and missiology, research methods and missionary contributions to ethnology, missionary training and methods, and specific case studies are presented. The ten essays are: (1) "An Ethnoethnography of Missionaries in Kalingaland" (Robert Lawless); (2) "Missionization and Social Change in Africa: The Case of the Church of the Brethren Mission/Ekklesiyar Yan'Uwa Nigeria in Northeastern Nigeria" (Philip Kulp); (3) "The Summer Institute -

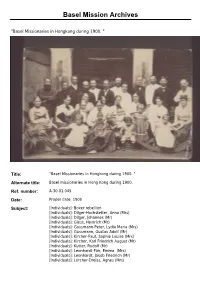

"Basel Missionaries in Hongkong During 1900. "

Basel Mission Archives "Basel Missionaries in Hongkong during 1900. " Title: "Basel Missionaries in Hongkong during 1900. " Alternate title: Basel missionaries in Hong Kong during 1900. Ref. number: A-30.01.045 Date: Proper date: 1900 Subject: [Individuals]: Boxer rebellion [Individuals]: Dilger-Hochstetter, Anna (Mrs) [Individuals]: Dilger, Johannes (Mr) [Individuals]: Giess, Heinrich (Mr) [Individuals]: Gussmann-Peter, Lydia Maria (Mrs) [Individuals]: Gussmann, Gustav Adolf (Mr) [Individuals]: Kircher-Faut, Sophie Louise (Mrs) [Individuals]: Kircher, Karl Friedrich August (Mr) [Individuals]: Kutter, Rudolf (Mr) [Individuals]: Leonhardt-Fäh, Emma (Mrs) [Individuals]: Leonhardt, Jakob Friedrich (Mr) [Individuals]: Lörcher-Dreiss, Agnes (Mrs) Basel Mission Archives [Individuals]: Lörcher, Jakob Gottlob (Mr) [Individuals]: Lutz, Samuel (Mr) [Individuals]: Ott-Walther, Wilhelmine Juliane (Mrs) [Individuals]: Ott, Rudolf (Mr) [Individuals]: Reusch-Keller, Pauline (Mrs) [Individuals]: Reusch, Christian Gottlieb (Mr) [Individuals]: Rohde, Hermann (Mr) [Individuals]: Schultze, Maria Rudolfine Agnes (child) [Individuals]: Schultze, Otto Karl Eduard (Mr) [Individuals]: Ziegler, Johann Georg (Mr) [Individuals]: Schultze-Michel, Sophie (Mrs) [Individuals]: Rohde-Kopp, Rosina Christ. (Mrs) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Dilger, Johannes (Mr) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Giess, Heinrich (Mr) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Lutz, Samuel (Mr) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Reusch, Christian Gottlieb (Mr) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Schultze,