A History of Russia College Outline Series (1955).Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grandmama of Europe: the Crowned Descendants of Queen Victoria Free Download

GRANDMAMA OF EUROPE: THE CROWNED DESCENDANTS OF QUEEN VICTORIA FREE DOWNLOAD Theo Aronson | 680 pages | 19 Nov 2014 | Thistle Publishing | 9781910198049 | English | United States Grandmama of Europe; the crowned descendants of Queen Victoria A very Grandmama of Europe: The Crowned Descendants of Queen Victoria book by Mr. Louise of Denmark. Paul of Greece [N Grandmama of Europe: The Crowned Descendants of Queen Victoria. A great starting off point as the book gives a very clear picture of those descendants of Queen Victoria who later became European monarchs. A woman of progressive opinions and… More. Seller Inventory Loved reading this piece of non-fic! About this Item: Theo Aronson, Sibylla of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. I must admit, it was difficult trying to keep track of all the whose who, and how they were all connected Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine. The author has used many many letters from Queen Victoria to her children and grandchildren and theirs to her, so there is a lot of pr I enjoyed this book greatly. All orders are dispatched the following working day from our UK warehouse. A re-release of a book originally published inthe coverage ends before the reigns of Juan Carlos of Spain or Carl Gustav of Sweden. Sophia Queen of the Hellenes. However, these two marriages were not the only unions amongst and between descendants of Victoria and Christian IX. Very thoroughly researched and includes many anecdotes. Tamara rated it it was amazing Jul 14, Great insight into the influence that Queen Victoria's progeny had over the world and how even those familial relationships couldn't stop the coming of WWI. -

The Memoirs of General the Baron De Marbot in 2 Volumes

The Memoirs of General the Baron de Marbot in 2 Volumes by the Baron de Marbot THE MEMOIRS OF GENERAL THE BARON DE MARBOT. Table of Contents THE MEMOIRS OF GENERAL THE BARON DE MARBOT......................................1 Volume I....................................................................2 Introduction...........................................................2 Chap. 1................................................................6 Chap. 2...............................................................11 Chap. 3...............................................................17 Chap. 4...............................................................24 Chap. 5...............................................................31 Chap. 6...............................................................39 Chap. 7...............................................................41 Chap. 8...............................................................54 Chap. 9...............................................................67 Chap. 10..............................................................75 Chap. 11..............................................................85 Chap. 12..............................................................96 Chap. 13.............................................................102 Chap. 14.............................................................109 Chap. 15.............................................................112 Chap. 16.............................................................122 Chap. 17.............................................................132 -

{FREE} Napoleon Bonaparte Ebook

NAPOLEON BONAPARTE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gregory Fremont-Barnes,Peter Dennis | 64 pages | 25 May 2010 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781846034589 | English | Oxford, England, United Kingdom Napoleon Bonaparte - Quotes, Death & Facts - Biography They may have presented themselves as continental out of a desire for honor and distinction, but this does not prove they really were as foreign as they themselves often imagined. We might say that they grew all the more attached to their Italian origins as they moved further and further away from them, becoming ever more deeply integrated into Corsican society through marriages. This was as true of the Buonapartes as of anyone else related to the Genoese and Tuscan nobilities by virtue of titles that were, to tell the truth, suspect. The Buonapartes were also the relatives, by marriage and by birth, of the Pietrasentas, Costas, Paraviccinis, and Bonellis, all Corsican families of the interior. Napoleon was born there on 15 August , their fourth child and third son. A boy and girl were born first but died in infancy. Napoleon was baptised as a Catholic. Napoleon was born the same year the Republic of Genoa ceded Corsica to France. His father was an attorney who went on to be named Corsica's representative to the court of Louis XVI in The dominant influence of Napoleon's childhood was his mother, whose firm discipline restrained a rambunctious child. Napoleon's noble, moderately affluent background afforded him greater opportunities to study than were available to a typical Corsican of the time. When he turned 9 years old, [18] [19] he moved to the French mainland and enrolled at a religious school in Autun in January Napoleon was routinely bullied by his peers for his accent, birthplace, short stature, mannerisms and inability to speak French quickly. -

Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906

Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906 Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906 A Century of Restorations Originally published as Das Jahrhundert der Restaurationen, 1814 bis 1906, Munich: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2014. Translated by Volker Sellin An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License, as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-052177-1 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-052453-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-052209-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover Image: Louis-Philippe Crépin (1772–1851): Allégorie du retour des Bourbons le 24 avril 1814: Louis XVIII relevant la France de ses ruines. Musée national du Château de Versailles. bpk / RMN - Grand Palais / Christophe Fouin. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Introduction 1 France1814 8 Poland 1815 26 Germany 1818 –1848 44 Spain 1834 63 Italy 1848 83 Russia 1906 102 Conclusion 122 Bibliography 126 Index 139 Introduction In 1989,the world commemorated the outbreak of the French Revolution two hundred years earlier.The event was celebratedasthe breakthrough of popular sovereignty and modernconstitutionalism. -

The History of World Civilization. 3 Cyclus (1450-2070) New Time ("New Antiquity"), Capitalism ("New Slaveownership"), Upper Mental (Causal) Plan

The history of world civilization. 3 cyclus (1450-2070) New time ("new antiquity"), capitalism ("new slaveownership"), upper mental (causal) plan. 19. 1450-1700 -"neoarchaics". 20. 1700-1790 -"neoclassics". 21. 1790-1830 -"romanticism". 22. 1830-1870 – «liberalism». Modern time (lower intuitive plan) 23. 1870-1910 – «imperialism». 24. 1910-1950 – «militarism». 25.1950-1990 – «social-imperialism». 26.1990-2030 – «neoliberalism». 27. 2030-2070 – «neoromanticism». New history. We understand the new history generally in the same way as the representatives of Marxist history. It is a history of establishment of new social-economic formation – capitalism, which, in difference to the previous formations, uses the economic impelling and the big machine production. The most important classes are bourgeoisie and hired workers, in the last time the number of the employees in the sphere of service increases. The peasants decrease in number, the movement of peasants into towns takes place; the remaining peasants become the independent farmers, who are involved into the ware and money economy. In the political sphere it is an epoch of establishment of the republican system, which is profitable first of all for the bourgeoisie, with the time the political rights and liberties are extended for all the population. In the spiritual plan it is an epoch of the upper mental, or causal (later lower intuitive) plan, the humans discover the laws of development of the world and man, the traditional explanations of religion already do not suffice. The time of the swift development of technique (Satan was loosed out of his prison, according to Revelation 20.7), which causes finally the global ecological problems. -

The Education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov The

Agata Strzelczyk DOI: 10.14746/bhw.2017.36.8 Department of History Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań The education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov Abstract This article concerns two very different ways and methods of upbringing of two Russian tsars – Alexander the First and Nicholas the First. Although they were brothers, one was born nearly twen- ty years before the second and that influenced their future. Alexander, born in 1777 was the first son of the successor to the throne and was raised from the beginning as the future ruler. The person who shaped his education the most was his grandmother, empress Catherine the Second. She appoint- ed the Swiss philosopher La Harpe as his teacher and wanted Alexander to become the enlightened monarch. Nicholas, on the other hand, was never meant to rule and was never prepared for it. He was born is 1796 as the ninth child and third son and by the will of his parents, Tsar Paul I and Tsarina Maria Fyodorovna he received education more suitable for a soldier than a tsar, but he eventually as- cended to the throne after Alexander died. One may ask how these differences influenced them and how they shaped their personalities as people and as rulers. Keywords: Romanov Children, Alexander I and Nicholas I, education, upbringing The education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov Among the ten children of Tsar Paul I and Tsarina Maria Feodorovna, two sons – the oldest Alexander and Nicholas, the second youngest son – took the Russian throne. These two brothers and two rulers differed in many respects, from their characters, through poli- tics, views on Russia’s place in Europe, to circumstances surrounding their reign. -

Eugene Miakinkov

Russian Military Culture during the Reigns of Catherine II and Paul I, 1762-1801 by Eugene Miakinkov A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta ©Eugene Miakinkov, 2015 Abstract This study explores the shape and development of military culture during the reign of Catherine II. Next to the institutions of the autocracy and the Orthodox Church, the military occupied the most important position in imperial Russia, especially in the eighteenth century. Rather than analyzing the military as an institution or a fighting force, this dissertation uses the tools of cultural history to explore its attitudes, values, aspirations, tensions, and beliefs. Patronage and education served to introduce a generation of young nobles to the world of the military culture, and expose it to its values of respect, hierarchy, subordination, but also the importance of professional knowledge. Merit is a crucial component in any military, and Catherine’s military culture had to resolve the tensions between the idea of meritocracy and seniority. All of the above ideas and dilemmas were expressed in a number of military texts that began to appear during Catherine’s reign. It was during that time that the military culture acquired the cultural, political, and intellectual space to develop – a space I label the “military public sphere”. This development was most clearly evident in the publication, by Russian authors, of a range of military literature for the first time in this era. The military culture was also reflected in the symbolic means used by the senior commanders to convey and reinforce its values in the army. -

Russian Art, Icons + Antiques

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES International auction 872 1401 - 1580 RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including The Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection International auction 872 AUCTION Friday 9 June 2017, 2 pm PREVIEW Wednesday 24 May 3 pm - 6 pm Thursday 25 May Public Holiday Friday 26 May 11 am - 5 pm Saturday 27 May 11 am - 4 pm Sunday 28 May 11 am - 4 pm Monday 29 May 11 am - 5 pm or by appointment Bredgade 33 · DK-1260 Copenhagen K · Tel +45 8818 1111 · Fax +45 8818 1112 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.com 872_russisk_s001-188.indd 1 28/04/17 16.28 Коллекция коммерческого атташе Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена и другие русские шедевры В течение 19 века Россия переживала стремительную трансформацию - бушевала индустриализация, модернизировалось сельское хозяйство, расширялась инфраструктура и создавалась обширная телеграфная система. Это представило новые возможности для международных деловых отношений, и известные компании, такие как датская Бурмэйстер энд Вэйн (В&W), Восточно-Азиатская Компания (EAC) и Компания Грэйт Норсерн Телеграф (GNT) открыли офисы в России и внесли свой вклад в развитие страны. Большое количество скандинавов выехало на Восток в поисках своей удачи в растущей деловой жизни и промышленности России. Среди многочисленных путешественников возникало сильное увлечение культурой страны, что привело к созданию высококачественных коллекций русского искусства. Именно по этой причине сегодня в Скандинавии так много предметов русского антиквариата, некоторые из которых будут выставлены на этом аукционе. Самые значимые из них будут ещё до аукциона выставлены в посольстве Дании в Лондоне во время «Недели Русского Искусства». Для более подробной информации смотри страницу 9. Изюминкой аукциона, без сомнения, станет Русская коллекция Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена, норвежского коммерческого атташе. -

History of the German Struggle for Liberty

MAN STRUG "i L UN SAN DIE6O CHARLES S. LANDERS, NEW BRITAIN, CONN. DATE, .203 HOW THE ALLIED TROOPS MARCHED INTO PARIS HISTORY OF THE GERMAN STRUGGLE FOR LIBERTY BY POULTNEY BIGELOW, B.A. ILLUSTRATED WITH DRAWINGS By R. CATON WOODVILLE AND WITH PORTRAITS AND MAPS IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. II. NEW YORK HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS 1896 Copyright, 189G, by HARPER & BROTHERS. All rigJiU rtltntd. CONTENTS OF VOL. II CUAPTEtt PAGB I. FREDERICK WILLIAM DESPAIRS OP nis COUNTRY 1811. 1 II. NAPOLEON ON THE EVE OF Moscow 9 III. THE FRENCH ARMY CONQUERS A WILDERNESS ... 18 IV. NAPOLEON TAKES REFUGE IN PRUSSIA 30 V. GENERAL YORCK, THE GLORIOUS TRAITOR 39 VI. THE PRUSSIAN CONGRESS OF ROYAL REBELS .... 50 VII. THE PRUSSIAN KING CALLS FOR VOLUNTEERS . C2 VIII. A PROFESSOR DECLARES WAR AGAINST NAPOLEON. 69 IX. THE ALTAR OF GERMAN LIBERTY 1813 ..... 80 X. THE GERMAN SOLDIER SINGS OF LIBERTY 87 XI. THE GERMAN FREE CORPS OF LUTZOW 95 XII. How THE PRUSSIAN KING WAS FINALLY FORCED TO DECLARE WAR AGAINST NAPOLEON 110 XIII. PRUSSIA'S FORLORN HOPE IN 1813 THE LANDSTURM . 117 XIV. LUTZEN '.'........"... 130 XV. SOME UNEXPECTED FIGHTS IN THE PEOPLE'S WAR. 140 XVI. NAPOLEON WINS ANOTHER BATTLE, BUT LOSES HIS TEMPER 157 XVII. BLUCHER CUTS A FRENCH ARMY TO PIECES AT THE KATZBACII 168 XVIII. THE PRUSSIANS WIN BACK WHAT THE AUSTRIANS HAD LOST 176 XIX. THE FRENCH TRY TO TAKE BERLIN, BUT ARE PUT TO ROUT BY A GENERAL WHO DISOBEYS ORDERS . 183 XX. How THE BATTLE OF LEIPZIG COMMENCED . 192 v CONTENTS OF VOL. II CHAPTER VAGB XXI. -

Historische Literatur, 5. Band · 2007 · Heft 1 1 © Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden Gmbh, Sitz Stuttgart Redaktion

Band 5 2007 Heft 1 Historische HistLit Literatur Band 5 · 2007 · Heft 1 www.steiner-verlag.de Rezensionszeitschrift von Januar – März Franz Steiner Verlag Franz Steiner Verlag H-Soz-u-Kult ISSN 1611-9509 Historische Literatur Historische Veröffentlichungen von Clio-online, Nr. 1 Umschlag Bd. 4_4.indd 1 06.06.2007 13:14:37 Uhr Historische Literatur Rezensionszeitschrift von H-Soz-u-Kult Band 5 · 2007 · Heft 1 Veröffentlichungen von Clio-online, Nr. 1 Titelseiten Bd. 5_1.indd 1 06.06.2007 13:17:02 Uhr Historische Literatur Rezensionszeitschrift von H-Soz-u-Kult Herausgegeben von der Redaktion H-Soz-u-Kult Geschäftsführende Herausgeber Rüdiger Hohls / Irmgard Zündorf Technische Leitung Daniel Burckhardt / Felix Herrmann Titelseiten Bd. 5_1.indd 2 06.06.2007 13:17:02 Uhr Historische Literatur Rezensionszeitschrift von H-Soz-u-Kult Band 5 · 2007 · Heft 1 Titelseiten Bd. 5_1.indd 3 06.06.2007 13:17:02 Uhr Historische Literatur Rezensionszeitschrift von H-Soz-u-Kult Redaktionsanschrift H-Soz-u-Kult-Redaktion c/o Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Philosophische Fakultät I Institut für Geschichtswissenschaften Unter den Linden 6 D-10099 Berlin Telefon: ++49-(0)30/2093-2492 und -2542 Telefax: ++49-(0)30/2093-2544 E-Mail: [email protected] www: http://hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de ISSN 1611-9509 Titelseiten Bd. 5_1.indd 4 06.06.2007 13:17:02 Uhr Redaktion 1 Alte Geschichte 4 Blum, Hartmut; Wolters, Reinhard: Alte Geschichte studieren. Konstanz 2006. (Stefan Selbmann)......................................... 4 Dulinicz, Marek: Frühe Slawen im Gebiet zwischen unterer Weichsel und Elbe. Eine archäologische Studie. Neumünster 2006. -

0 Further Reading

0 Further reading General The best general introduction to the whole period is: Thomson, D., Europe since Napoleon (Penguin, 1966). There are also a number of good series available such as the Fontana History of Europe and Longman 's A General History of Europe. The relevant volumes in these series are as follows: Rude, G., Revolutionary Europe, 1783-1815 (Fontana, 1964). Droz, J., Europe between Revolutions, 1815-1848 (Fontana, 1967). Grenville, J.A.S., Europe Reshaped, 1848-1878 (Fontana, 1976). Stone, N., Europe Transformed, 1878-1919 (Fontana, 1983). Wiskemann, E., Europe of the Dictators, 1919-1945 (Fontana, 1966). Ford, F.L., Europe, 1780-1830 (Longman, 1967). Hearder, H., Europe in the Nineteenth Century, 1830-1880 (Longman, 1966). Roberts, J., Europe, 1880-1945 (Longman, 1967). For more specialist subjects there are various contributions by expert authorities included in: The New Cambridge Modern History, vols. IX-XII (Cambridge, 1957). Cipolla, C.M. (ed.), Fontana Economic History of Europe (Fontana, 1963). Other useful books of a general nature include: Hinsley, F.H., Power and the Pursuit of Peace (Cambridge University Press, 1963). Kennedy, P., Strategy and Diplomacy 1870-1945 (Allen & Unwin, 1983). Seaman, L.C.B., From Vienna to Versailles (Methuen, 1955). Seton-Watson, H., Nations and States (Methuen, 1977). Books of documentary extracts include: Brooks, S., Nineteenth Century Europe (Macmillan, 1983). Brown, R. and Daniels, C., Twentieth Century Europe (Macmillan, 1981). Welch, D., Modern European History, 1871-1975 (Heinemann, 1994). The Longman Seminar Studies in History series provides excellent introductions to debates and docu mentary extracts on a wide variety of subjects. -

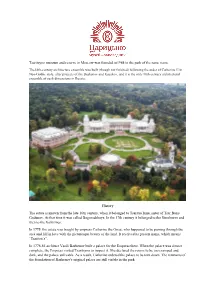

Tsaritsyno Museum and Reserve in Moscow Was Founded In1984 in the Park of the Same Name

Tsaritsyno museum and reserve in Moscow was founded in1984 in the park of the same name. The18th-century architecture ensemble was built (though not finished) following the order of Catherine II in Neo-Gothic style, after projects of the Bazhenov and Kazakov, and it is the only 18th-century architectural ensemble of such dimensions in Russia. History The estate is known from the late 16th century, when it belonged to Tsaritsa Irina, sister of Tsar Boris Godunov. At that time it was called Bogorodskoye. In the 17th century it belonged to the Streshnevs and then to the Galitzines. In 1775, the estate was bought by empress Catherine the Great, who happened to be passing through the area and fell in love with the picturesque beauty of the land. It received its present name, which means “Tsaritsa’s”. In 1776-85 architect Vasili Bazhenov built a palace for the Empress there. When the palace was almost complete, the Empress visited Tsaritsyno to inspect it. She declared the rooms to be too cramped and dark, and the palace unlivable. As a result, Catherine ordered the palace to be torn down. The remnants of the foundation of Bazhenov's original palace are still visible in the park. In 1786, Matvey Kazakov presented new architectural plans, which were approved by Catherine. Kazakov supervised the construction project until 1796 when the construction was interrupted by Catherine's death. Her successor, Emperor Paul I of Russia showed no interest in the palace and the massive structure remained unfinished and abandoned for more than 200 years, until it was completed and extensively reworked in 2005-07.