The Education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796

Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796 By Thomas Lucius Lowish A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Victoria Frede-Montemayor, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor Kinch Hoekstra Spring 2021 Abstract Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796 by Thomas Lucius Lowish Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Victoria Frede-Montemayor, Chair Historians of Russian monarchy have avoided the concept of sovereignty, choosing instead to describe how monarchs sought power, authority, or legitimacy. This dissertation, which centers on Catherine the Great, the empress of Russia between 1762 and 1796, takes on the concept of sovereignty as the exercise of supreme and untrammeled power, considered legitimate, and shows why sovereignty was itself the major desideratum. Sovereignty expressed parity with Western rulers, but it would allow Russian monarchs to bring order to their vast domain and to meaningfully govern the lives of their multitudinous subjects. This dissertation argues that Catherine the Great was a crucial figure in this process. Perceiving the confusion and disorder in how her predecessors exercised power, she recognized that sovereignty required both strong and consistent procedures as well as substantial collaboration with the broadest possible number of stakeholders. This was a modern conception of sovereignty, designed to regulate the swelling mechanisms of the Russian state. Catherine established her system through careful management of both her own activities and the institutions and servitors that she saw as integral to the system. -

Download Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional

Download Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF Book Download, PDF Download, Read PDF, Download PDF, Kindle Download Download Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF Download PDF File Download Kindle File Download ePub File Our website also provides Download Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF in many format, so don’t worry if readers want to download Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF Online that can’t be open through their device. Go and hurry up to download through our website. We guarantee that e-book in our website is the best and in high quality. Download Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF Bestselling Books Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF Download Free, The Last Mile (Amos Decker series), Memory Man... Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF Free Download The benefit you get by reading this book is actually information inside .. -

Hist Gosp T.Cdr

STUDIA Z HISTORII SPOŁECZNO-GOSPODARCZEJ 2011 Tom IX Lidia Jurek (Florencja) THE COMMUNICATIVE DIMENSION OF VIOLENCE: POLISH LEGIONS IN ITALY AS AN INSTRUMENT OF APPEAL TO “EUROPE” (1848–1849) In the late March 1848 Władysław Zamoyski stopped in Florence to visit the grave of his mother buried in the magnificent church of Santa Croce. Florence was on his half-way from Rome to Turin, two centers of the springing Risorgimento, where after long strivings the prince Czartoryski’s right hand man managed to obtain agreements about the formation of Polish Legions. It must have been soon after when Zamoyski received a letter from the Prince dated 22 nd of March with the words reacting to the outbreak of 1848 revolutions in Europe: “the scene, as you must know by now, has again changed completely. Berlin and Vienna – by far our enemies – suddenly transformed into our allies. Now the Italian Question becomes of secondary importance to us”1. This article intends to interpret this unexpected turnabout and recalling of Zamoyski’s Italian mission through the lens of the broader propaganda game Czartoryski conducted in Europe. By the same token, it will shed a new light on the function of Hôtel Lambert’s legions. Hôtel Lambert’s legionary activities in Italy were conventionally analyzed through their diplomatic character and their military efficiency. However, as Jerzy Skowronek observed, Czartoryski acted “in accordance with his impera- tive to make use of every, even the smallest and indirect, action to evoke the Polish cause, to provoke another manifestation of sympathy with it, to condemn the partitioning powers” 2. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) Russianness in the Works of European Composers Liudmila Kazantseva Department of Theory and History of Music Astrakhan State Concervatoire Astrakhan, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—For the practice of composing a conscious Russianness is seen more as an exotic). As one more reproduction of native or non-native national style is question I’ll name the ways and means of capturing Russian traditional. As the object of attention of European composers origin. are constantly featured national specificity of Russian culture. At the same time the “hit accuracy” ranges here from a Not turning further on the fan of questions that determine maximum of accuracy (as a rule, when finding a composer in the development of the problems of Russian as other- his native national culture) to a very distant resemblance. The national, let’s focus on only one of them: the reasons which out musical and musical reasons for reference to the Russian encourage European composers in one form or another to culture they are considered in the article. Analysis shows that turn to Russian culture and to make it the subject of a Russiannes is quite attractive for a foreign musicians. However creative image. the European masters are rather motivated by a desire to show, to indicate, to declare the Russianness than to comprehend, to II. THE OUT MUSICAL REASONS FOR REFERENCE TO THE go deep and to get used to it. RUSSIAN CULTURE Keywords—Russian music; Russianness; Western European In general, the reasons can be grouped as follows: out composers; style; polystyle; stylization; citation musical and musical. -

Eugene Miakinkov

Russian Military Culture during the Reigns of Catherine II and Paul I, 1762-1801 by Eugene Miakinkov A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta ©Eugene Miakinkov, 2015 Abstract This study explores the shape and development of military culture during the reign of Catherine II. Next to the institutions of the autocracy and the Orthodox Church, the military occupied the most important position in imperial Russia, especially in the eighteenth century. Rather than analyzing the military as an institution or a fighting force, this dissertation uses the tools of cultural history to explore its attitudes, values, aspirations, tensions, and beliefs. Patronage and education served to introduce a generation of young nobles to the world of the military culture, and expose it to its values of respect, hierarchy, subordination, but also the importance of professional knowledge. Merit is a crucial component in any military, and Catherine’s military culture had to resolve the tensions between the idea of meritocracy and seniority. All of the above ideas and dilemmas were expressed in a number of military texts that began to appear during Catherine’s reign. It was during that time that the military culture acquired the cultural, political, and intellectual space to develop – a space I label the “military public sphere”. This development was most clearly evident in the publication, by Russian authors, of a range of military literature for the first time in this era. The military culture was also reflected in the symbolic means used by the senior commanders to convey and reinforce its values in the army. -

Andrzej Szmyt Russia's Educational Policy Aimed at The

Andrzej Szmyt Russia’s Educational Policy Aimed at the Poles and the Polish Territories Annexed During the Reign of Tsar Alexander I Przegląd Wschodnioeuropejski 7/1, 11-28 2016 PRZEGLĄD WSCHODNIOEUROPEJSKI VII/1 2016: 11-28 A n d r z e j Szm y t University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn RUSSIA’S EDUCATIONAL POLICY AIMED AT THE POLES AND THE POLISH TERRITORIES ANNEXED DURING THE REIGN OF TSAR ALEXANDER I 1 Keywords: Russia, tsar Alexander I, the Russian partition of Poland, the history of education, the Vilnius Scientific District, Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski Abstract: The beginning of the 19th century in Russia marks the establishment of the modern system of education, to much extent based on the standards set by the National Commission of Education. Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski , then a close associate of Alexander I, used the young tsar’s enthusiasm for reforming the country, including the educational system. The already implemented reforms encompassed also the territories of the Russian partition. The unique feature of the Vilnius Scientific District created at that time was the possibility of teaching in the Polish language in all types of schools. It was the school superintendent Prince A. J. Czartoryski who deserved credit for that - due to his considerable influence upon the tsar’s policy towards the Poles. After the change in the position of the superintendent (1824) and the death of Alexander I (1825), the authorities’ policy on the Polish educational system became stricter, and after the fall of the November Uprising Polish educational institutions practically disappeared. The source base of the text is constituted by the archival materials stored in the State Historical Archives in Kiev and Vilnius as well as in the Library of The Vilnius University. -

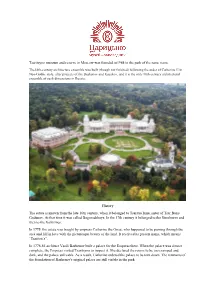

Tsaritsyno Museum and Reserve in Moscow Was Founded In1984 in the Park of the Same Name

Tsaritsyno museum and reserve in Moscow was founded in1984 in the park of the same name. The18th-century architecture ensemble was built (though not finished) following the order of Catherine II in Neo-Gothic style, after projects of the Bazhenov and Kazakov, and it is the only 18th-century architectural ensemble of such dimensions in Russia. History The estate is known from the late 16th century, when it belonged to Tsaritsa Irina, sister of Tsar Boris Godunov. At that time it was called Bogorodskoye. In the 17th century it belonged to the Streshnevs and then to the Galitzines. In 1775, the estate was bought by empress Catherine the Great, who happened to be passing through the area and fell in love with the picturesque beauty of the land. It received its present name, which means “Tsaritsa’s”. In 1776-85 architect Vasili Bazhenov built a palace for the Empress there. When the palace was almost complete, the Empress visited Tsaritsyno to inspect it. She declared the rooms to be too cramped and dark, and the palace unlivable. As a result, Catherine ordered the palace to be torn down. The remnants of the foundation of Bazhenov's original palace are still visible in the park. In 1786, Matvey Kazakov presented new architectural plans, which were approved by Catherine. Kazakov supervised the construction project until 1796 when the construction was interrupted by Catherine's death. Her successor, Emperor Paul I of Russia showed no interest in the palace and the massive structure remained unfinished and abandoned for more than 200 years, until it was completed and extensively reworked in 2005-07. -

Note on Transliteration I Am Using the Library of Congress System Without

2 Note on Transliteration I am using the Library of Congress system without diacritics, with the following exceptions: - In the main text I have chosen to spell names ending in “skii” as “sky” (as in Zhukovsky) - I will use the common spelling of the names of noted Russian authors, such as Tolstoy 3 Introduction This dissertation focuses on three Russian poets—Aleksandr Pushkin, Mikhail Lermontov, and Vasily Zhukovsky, and on the handling of rusalka figures in their work. I claim that all three poets used the rusalka characters in their works as a means of expressing their innermost fantasies, desires, hopes, and fears about females and that there is a direct correlation between the poets’ personal lives and their experiences with women and the rusalka characters in their works. Aleksandr Pushkin used the rusalka figure in two of his poems¾the short whimsical poem “Rusalka” written in 1819, and the longer more serious poetic drama “Rusalka” that he started in 1829 and never finished. The ways in which Pushkin uses the rusalka characters in these works represent his growth and development in terms of experiencing and understanding women’s complex internal worlds and women’s role in his personal and professional life. I claim that the 1819 poem “Rusalka” represents the ideas that Pushkin had early on in his life associated with a power struggle between men and women and his fears related to women, whom he viewed as simplistic, unpredictable, and irrational, with the potential of assuming control over men through their beauty and sexuality and potentially using that control to lead men to their downfall. -

Russia's Empress-Navigator

Russia’s Empress-Navigator: Transforming Modes of Monarchy During the Reign of Anna Ivanovna, 1730-1740 Jacob Bell University of Illinois 2019 Winner of the James Madison Award for Excellence in Historical Scholarship The eighteenth century was a markedly volatile period in the history of Russia, seeing its development and international emergence as a European-styled empire. In narratives of this time of change, historians tend to view the century in two parts: the reign of Peter I (r. 1682-1725), who purportedly spurred Russia into modernization, and Catherine II (r. 1762-96), the German princess-turned-empress who presided over the culmination of Russia’s transformation. Yet, dismissal of nearly forty years of Russia’s history does a severe disservice to the sovereigns and governments that formed the process of change. Recently, Catherine Evtuhov turned her attention to investigating Russia under the rule of Elizabeth Petrovna (r. 1741-62), bolstering the conversation with a greater perspective of one of these “forgotten reigns,” but Elizabeth owed much to her post-Petrine predecessors. Specifically, Empress Anna Ivanovna (r. 1730-40) remains one of the most overlooked and underappreciated sovereigns of the interim between the “Greats.”1 Anna Ivanovna was born on February 7, 1693, the daughter of Praskovia Saltykova and Ivan V Alekseyvich (r. 1682-96), the son of Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich (r. 1645-1676). When Anna was 1 Anna’s patronymic is also transliterated as Anna Ioannovna. I elected to use “Ivanovna” to closer resemble modern Russian. Lindsey Hughes, Russia in the Age of Peter the Great (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998); Catherine Evtuhov’s upcoming book is Russia in the Age of Elizabeth (1741-61). -

15/35/54 Liberal Arts and Sciences Russian & East European Center

15/35/54 Liberal Arts and Sciences Russian & East European Center Paul B. Anderson Papers, 1909-1988 Papers of Paul B. Anderson (1894-1985), including correspondence, maps, notes, reports, photographs, publications and speeches about the YMCA World Service (1919-58), International Committee (1949-78), Russian Service (1917-81), Paris Headquarters (1922-67) and Press (1919-80); American Council of Voluntary Agencies (1941-47); Anglican-Orthodox Documents & Joint Doctrinal Commission (1927-77); China (1913-80); East European Fund & Chekhov Publishing House (1951-79); displaced persons (1940-52); ecumenical movement (1925-82); National Council of Churches (1949-75); prisoners of war (1941-46); Religion in Communist Dominated Areas (1931-81); religion in Russia (1917-82); Russian Correspondence School (1922-41); Russian emigrés (1922-82); Russian Orthodox Church (1916-81) and seminaries (1925-79); Russian Student Christian Movement (1920-77); Tolstoy Foundation (1941-76) and War Prisoners Aid (1916-21). For an autobiographical account, see Donald E. Davis, ed., No East or West: The Memoirs of Paul B. Anderson (Paris: YMCA-Press, 1985). For Paul Anderson's "Reflections on Religion in Russia, 1917-1967" and a bibliography, see Richard H. Marshall Jr., Thomas E. Bird and Andrew Q. Blane, Eds., Aspects of Religion in the Soviet Union 1917-1967 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1971). Provenance Note: The Paul B. Anderson Papers first arrived at the University Archives on May 16, 1983. They were opened on September 11, 1984 and a finding aid completed on December 15, 1984. The cost of shipping the papers and the reproduction of the finding aid was borne by the Russian and East European Center. -

Super-Heroes of the Orchestra

S u p e r - Heroes of the Orchestra TEACHER GUIDE THIS BELONGS TO: _________________________ 1 Dear Teachers: The Arkansas Symphony Orchestra is presenting SUPER-HEROES OF THE SYMPHONY this year to area students. These materials will help you integrate the concert experience into the classroom curriculum. Music communicates meaning just like literature, poetry, drama and works of art. Understanding increases when two or more of these media are combined, such as illustrations in books or poetry set to music ~~ because multiple senses are engaged. ABOUT ARTS INTEGRATION: As we prepare students for college and the workforce, it is critical that students are challenged to interpret a variety of ‘text’ that includes art, music and the written word. By doing so, they acquire a deeper understanding of important information ~~ moving it from short-term to long- term memory. Music and art are important entry points into mathematical and scientific understanding. Much of the math and science we teach in school are innate to art and music. That is why early scientists and mathematicians, such as Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Pythagoras, were also artists and musicians. This Guide has included literacy, math, science and social studies lesson planning guides in these materials that are tied to grade-level specific Arkansas State Curriculum Framework Standards. These lesson planning guides are designed for the regular classroom teacher and will increase student achievement of learning standards across all disciplines. The students become engaged in real-world applications of key knowledge and skills. (These materials are not just for the Music Teacher!) ABOUT THE CONTENT: The title of this concert, SUPER-HEROES OF THE SYMPHONY, suggests a focus on musicians/instruments/real and fictional people who do great deeds to help achieve a common goal.