Super-Heroes of the Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional

Download Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF Book Download, PDF Download, Read PDF, Download PDF, Kindle Download Download Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF Download PDF File Download Kindle File Download ePub File Our website also provides Download Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF in many format, so don’t worry if readers want to download Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF Online that can’t be open through their device. Go and hurry up to download through our website. We guarantee that e-book in our website is the best and in high quality. Download Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF Bestselling Books Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF Download Free, The Last Mile (Amos Decker series), Memory Man... Vasily Zhukovsky's Romanticism and the Emotional History of Russia (Northwestern University Press Studies in Russian Literature and Theory) by Ilya Vinitsky (2015-05-31) PDF Free Download The benefit you get by reading this book is actually information inside .. -

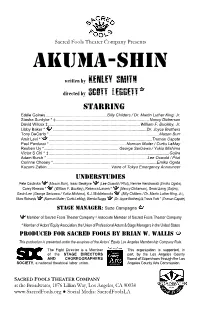

AKUMA-SHIN Is a Rumination on the Shadow, the Lurking Unknown of Nightmare

Sacred Fools Theater Company Presents Akuma- shin written by Kenley Smith directed by Scott Leggett Starring Eddie Goines.......................................................Billy Childers / Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Stasha Surdyke * ‡................................................................................... Nancy Dickerson David Wilcox ‡.................................................................................. William F. Buckley, Jr. Libby Baker * ...................................................................................Dr. Joyce Brothers Tony DeCarlo *.................................................................................................. Mason Burr Amir Levi * ............................................................................................Truman Capote Paul Parducci *.....................................................................Norman Mailer / Curtis LeMay Reuben Uy *.................................................................. George Serizawa / Yukio Mishima Victor S Chi * ‡........................................................................................................... Gojira Adam Burch * ..........................................................................................Lee Oswald / Pilot Corinne Chooey *............................................................................................Emiko Ogata Kazumi Zatkin......................................................... Voice of Tokyo Emergency Announcer Understudies Pete Caslavka (Mason Burr), -

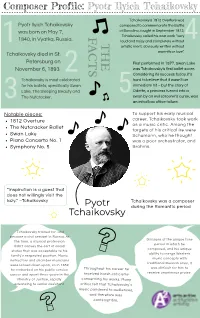

Download This Composer Profile Here

Composer Profile: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed to commemorate the Battle was born on May 7, of Borodino, fought in September 1812, F Tchaikovsky called his own work “very 1840, in Vyatka, Russia. loud and noisy and completely without THE A 4 1 artistic merit, obviously written without Tchaikovsky died in St. CTS warmth or love”. Petersburg on First performed in 1877, Swan Lake November 6, 1893. was Tchaikovsky’s first ballet score. 2 Considering its success today, it's Tchaikovsky is most celebrated hard to believe that it wasn’t an for his ballets, specifically Swan immediate hit – but the story of Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and Odette, a princess turned into a The Nutcracker. 5 swan by an evil sorcerer's curse, was 3 an initial box office failure. Notable pieces: To support his early musical 1812 Overture career, Tchaikovsky took work as a music critic. Among the The Nutcracker Ballet targets of his critical ire were Swan Lake Schumann, who he thought Piano Concerto No. 1 was a poor orchestrator, and Symphony No. 5 Brahms. “Inspiration is a guest that does not willingly visit the lazy.” –Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky was a composer I'mPy oOtrne! during the Romantic period Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky trained for, and became a civil servant in Russia. At Because of the unique time the time, a musical profession period in which he didn’t convey the sort of social composed, and his unique status that was acceptable to his ability to merge Western family’s respected position. Music music concepts with instructors and chamber musicians traditional Russian ones, it were looked down upon, so in 1859 was difficult for him to he embarked on his public service Throughout his career he receive unanimous praise. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Die Flexible Welt Der Simpsons

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Lehmann Die flexible Welt der Simpsons 2012 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die flexible Welt der Simpsons Autor: Herr Benjamin Lehmann Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08w2-B Erstprüfer: Professor Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Christian Maintz (M.A.) Einreichung: Mittweida, 06.01.2012 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The flexible world of the Simpsons author: Mr. Benjamin Lehmann course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08w2-B first examiner: Professor Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Christian Maintz (M.A.) submission: Mittweida, 6th January 2012 Bibliografische Angaben Lehmann, Benjamin: Die flexible Welt der Simpsons The flexible world of the Simpsons 103 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2012 Abstract Die Simpsons sorgen seit mehr als 20 Jahren für subversive Unterhaltung im Zeichentrickformat. Die Serie verbindet realistische Themen mit dem abnormen Witz von Cartoons. Diese Flexibilität ist ein bestimmendes Element in Springfield und erstreckt sich über verschiedene Bereiche der Serie. Die flexible Welt der Simpsons wird in dieser Arbeit unter Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen auf den Wiedersehenswert der Serie untersucht. 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................... 7 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................... -

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) Russianness in the Works of European Composers Liudmila Kazantseva Department of Theory and History of Music Astrakhan State Concervatoire Astrakhan, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—For the practice of composing a conscious Russianness is seen more as an exotic). As one more reproduction of native or non-native national style is question I’ll name the ways and means of capturing Russian traditional. As the object of attention of European composers origin. are constantly featured national specificity of Russian culture. At the same time the “hit accuracy” ranges here from a Not turning further on the fan of questions that determine maximum of accuracy (as a rule, when finding a composer in the development of the problems of Russian as other- his native national culture) to a very distant resemblance. The national, let’s focus on only one of them: the reasons which out musical and musical reasons for reference to the Russian encourage European composers in one form or another to culture they are considered in the article. Analysis shows that turn to Russian culture and to make it the subject of a Russiannes is quite attractive for a foreign musicians. However creative image. the European masters are rather motivated by a desire to show, to indicate, to declare the Russianness than to comprehend, to II. THE OUT MUSICAL REASONS FOR REFERENCE TO THE go deep and to get used to it. RUSSIAN CULTURE Keywords—Russian music; Russianness; Western European In general, the reasons can be grouped as follows: out composers; style; polystyle; stylization; citation musical and musical. -

African Drumming in Drum Circles by Robert J

African Drumming in Drum Circles By Robert J. Damm Although there is a clear distinction between African drum ensembles that learn a repertoire of traditional dance rhythms of West Africa and a drum circle that plays primarily freestyle, in-the-moment music, there are times when it might be valuable to share African drumming concepts in a drum circle. In his 2011 Percussive Notes article “Interactive Drumming: Using the power of rhythm to unite and inspire,” Kalani defined drum circles, drum ensembles, and drum classes. Drum circles are “improvisational experiences, aimed at having fun in an inclusive setting. They don’t require of the participants any specific musical knowledge or skills, and the music is co-created in the moment. The main idea is that anyone is free to join and express himself or herself in any way that positively contributes to the music.” By contrast, drum classes are “a means to learn musical skills. The goal is to develop one’s drumming skills in order to enhance one’s enjoyment and appreciation of music. Students often start with classes and then move on to join ensembles, thereby further developing their skills.” Drum ensembles are “often organized around specific musical genres, such as contemporary or folkloric music of a specific culture” (Kalani, p. 72). Robert Damm: It may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music for the sake of enhancing the musical skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience of the participants. PERCUSSIVE NOTES 8 JULY 2017 PERCUSSIVE NOTES 9 JULY 2017 cknowledging these distinctions, it may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music (culturally specific rhythms, processes, and concepts) for the sake of enhancing the musi- cal skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience Aof the participants in a drum circle. -

The Education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov The

Agata Strzelczyk DOI: 10.14746/bhw.2017.36.8 Department of History Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań The education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov Abstract This article concerns two very different ways and methods of upbringing of two Russian tsars – Alexander the First and Nicholas the First. Although they were brothers, one was born nearly twen- ty years before the second and that influenced their future. Alexander, born in 1777 was the first son of the successor to the throne and was raised from the beginning as the future ruler. The person who shaped his education the most was his grandmother, empress Catherine the Second. She appoint- ed the Swiss philosopher La Harpe as his teacher and wanted Alexander to become the enlightened monarch. Nicholas, on the other hand, was never meant to rule and was never prepared for it. He was born is 1796 as the ninth child and third son and by the will of his parents, Tsar Paul I and Tsarina Maria Fyodorovna he received education more suitable for a soldier than a tsar, but he eventually as- cended to the throne after Alexander died. One may ask how these differences influenced them and how they shaped their personalities as people and as rulers. Keywords: Romanov Children, Alexander I and Nicholas I, education, upbringing The education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov Among the ten children of Tsar Paul I and Tsarina Maria Feodorovna, two sons – the oldest Alexander and Nicholas, the second youngest son – took the Russian throne. These two brothers and two rulers differed in many respects, from their characters, through poli- tics, views on Russia’s place in Europe, to circumstances surrounding their reign. -

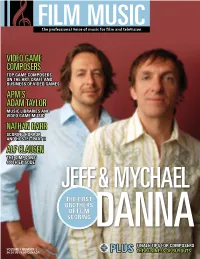

Video Game Composers Apm's Adam Taylor Nathan Barr

FILM MUSIC pdalnkbaooekj]hrke_akbiqoe_bknbehi]j`pahareoekj VIDEO GAME COMPOSERS TOP GAME COMPOSERS ON THE ART, CRAFT AND BUSINESS OF VIDEO GAMES APM’S ADAM TAYLOR MUSIC LIBRARIES AND VIDEO GAME MUSIC NATHAN BARR SCORING HORROR AND HOSTEL: PART II ALF CLAUSEN THE SIMPSONS’ 400TH EPISODE JEFF & MYCHAEL THE FIRST BROTHERS OF FILM SCORING DANNA FINALE TIPS FOR COMPOSERS RKHQIA3JQI>AN/ 2*1,QO 4*1,?=J=@= + PLUS THE BUSINESS OF BUYOUTS RE@AKC=IA?KILKOANO 5GD8NQKCNE (".& $0.104*/( BY PETER LAWRENCE ALEXANDER WITH GREG O’CONNOR-READ 14 ! filmmusicmag.com In a rapidly changing technological environment that’s highly competitive, composers the world over are looking for new opportunities that enable them to score music, and for a livable wage. One of the emerging arenas for this is game scoring. Originally the domain of all synth/sample scores, game music now uses full orchestras, along with synth/sample libraries. To gain a feel for this industry, and to help you, the reader, decide if game scoring is something you want to pursue, Film Music Magazine has established an unprecedented panel in print: six top video game composers with varying styles and musical tastes, plus top game composer agent Bob Rice of Four Bars Intertainment. As you read the interviews, it will become quickly apparent that while there are many Let’s pretend that you’ve started a new music school course just for game composers. Given your experience, similarities between film and TV, and game what would you insist every student learn to master, and scoring, one major difference arises that is why? Rod Abernethy and Jason Graves:E^Zkgrhnklmk^g`mal literally within the mind of the composer. -

Explore Music 7 World Drumming.Pdf (PDF 2.11

Explore Music 7: World Drumming Explore Music 7: World Drumming (Revised 2020) Page 1 Explore Music 7: World Drumming (Revised 2020) Page 2 Contents Explore Music 7: World Drumming Overview ........................................................................................................................................5 Unit 1: The Roots of Drumming (4-5 hours)..................................................................................7 Unit 2: Drum Circles (8-10 hours) .................................................................................................14 Unit 3: Ensemble Playing (11-14 hours) ........................................................................................32 Supporting Materials.......................................................................................................................50 References.................................................. ....................................................................................69 The instructional hours indicated for each unit provide guidelines for planning, rather than strict requirements. The sequence of skill and concept development is to be the focus of concern. Teachers are encouraged to adapt these suggested timelines to meet the needs of their students. To be effective in teaching this module, it is important to use the material contained in Explore Music: Curriculum Framework and Explore Music: Appendices. Therefore, it is recommended that these two components be frequently referenced to support the suggestions for -

Land- En Volkenkunde

Music of the Baduy People of Western Java Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal- , Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte (kitlv, Leiden) Henk Schulte Nordholt (kitlv, Leiden) Editorial Board Michael Laffan (Princeton University) Adrian Vickers (The University of Sydney) Anna Tsing (University of California Santa Cruz) volume 313 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ vki Music of the Baduy People of Western Java Singing is a Medicine By Wim van Zanten LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY- NC- ND 4.0 license, which permits any non- commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https:// creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by- nc- nd/ 4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: Front: angklung players in Kadujangkung, Kanékés village, 15 October 1992. Back: players of gongs and xylophone in keromong ensemble at circumcision festivities in Cicakal Leuwi Buleud, Kanékés, 5 July 2016. Translations from Indonesian, Sundanese, Dutch, French and German were made by the author, unless stated otherwise. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2020045251 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto Friday, January 12, 2018 at 11 am Jayce Ogren, Guest conductor Sibelius Symphony No. 7 in C Major Tchaikovsky Concerto for Violin and Orchestra Gabriel Lefkowitz, violin Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto For Tchaikovsky and The Composers Sibelius, these works were departures from their previ- ous compositions. Both Jean Sibelius were composed in later pe- (1865—1957) riods in these composers’ lives and both were pushing Johan Christian Julius (Jean) Sibelius their comfort levels. was born on December 8, 1865 in Hämeenlinna, Finland. His father (a doctor) died when Jean For Tchaikovsky, the was three. After his father’s death, the family Violin Concerto came on had to live with a variety of relatives and it was Jean’s aunt who taught him to read music and the heels of his “year of play the piano. In his teen years, Jean learned the hell” that included his disas- violin and was a quick study. He formed a trio trous marriage. It was also with his sister older Linda (piano) and his younger brother Christian (cello) and also start- the only concerto he would ed composing, primarily for family. When Jean write for the violin. was ready to attend university, most of his fami- Jean Sibelius ly (Christian stayed behind) moved to Helsinki For Sibelius, his final where Jean enrolled in law symphony became a chal- school but also took classes at the Helsinksi Music In- stitute. Sibelius quickly became known as a skilled vio- lenge to synthesize the tra- linist as well as composer. He then spent the next few ditional symphonic form years in Berlin and Vienna gaining more experience as a composer and upon his return to Helsinki in 1892, he with a tone poem.