Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Angel Cried out (1887) | Angel Vopiyashe 2:57

PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840–1893) All-Night Vigil, Op. 52 (1881) An Essay in Harmonizing liturgical chants Vsenoshchnoye bdeniye Opït garmonizatsiy bogosluzehbnïh pesnopeniy 1. Bless the Lord, O My Soul | Blagoslovi, dushe moya, Ghospoda 6:48 2. Kathisma: Blessed is the Man | Kafizma: Blazhen muzh 3:20 3. Lord, I Call | Ghospodi, vozzvah 0:58 4. Gladsome Light | Svete tihiy 2:25 5. Rejoice, O Virgin | Bogoroditse Devo 0:44 6. The Lord is God | Bog Ghospod 1:02 7. Praise the Name of the Lord | Hvalite imia Ghospodne 4:00 8. Blessed Art Thou, O Lord | Blagosloven yesi, Ghospodi 4:29 9. From My Youth | Ot yunosti moyeya 1:42 10. Having Beheld the Resurrection of Christ | Voskreseniye Hristovo videvshe 2:14 11. Common Katavasia: I Shall Open My Lips | Katavasiya raidovaya: Otverzu usta moya 5:17 12. Theotokion: Thou Art Most Blessed | Bogorodichen: Preblagoslovenna yesi 1:21 13. The Great Doxology | Velikoye slavosloviye 6:40 14. To Thee, the Victorious Leader | Vzbrannoy voyevode 0:55 15. Hymn in Honour of Saints Cyril and Methodius (1885) | Gimn v chest Sv. Kirilla i Mefodiya 2:44 16. A Legend, Op. 54 No. 5 (1883) | Legenda 3:12 17. Jurists’ Song (1885) | Pravovedcheskaya pesn 2:02 18. The Angel Cried Out (1887) | Angel vopiyashe 2:57 Latvian Radio Choir SIGVARDS KĻAVA, conductor he Latvian Radio Choir, led by Sigvards Kļava, presents a second album of sacred works by TPeter Tchaikovsky for choir. As with the first, its centrepiece is an extensive multi-movement composition – in this case, the All-Night Vigil. -

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

Leevi Madetoja (1887–1947) Symphony No

Leevi Madetoja (1887–1947) Symphony No. 2 / Kullervo / Elegy 1. Kullervo, Symphonic Poem, Op. 15 14:13 Symphony No. 2, Op. 35 2. I. Allegro moderato – 13:23 LEEVI MADETOJA II. Andante 13:36 SYMPHONY NO. 2 III. Allegro non troppo – 9:39 KULLERVO IV. Andantino 4:53 ELEGY 3. Elegy, Op. 4/1 (First movement from the Symphonic Suite, Op. 4) 5:53 –2– Leevi Madetoja To be an orchestral composer in Finland as a contemporary of Sibelius and nevertheless create an independent composer profile was no mean feat, but Leevi Madetoja managed it. Though even he was not LEEVI MADETOJA completely immune to the influence of SYMPHONY NO. 2 his great colleague, he did find a voice for KULLERVO ELEGY himself where the elegiac nature of the landscape and folk songs of his native province of Ostrobothnia merged with a French elegance. Madetoja’s three symphonies did not follow the trail blazed by Sibelius, and another mark of his independence as a composer is that his principal works include two operas, Pohjalaisia (The Ostrobothnians, 1924) and Juha (1935), a genre that Sibelius never embraced. Madetoja emerged as a composer while still a student at the Helsinki Music Institute, when Robert Kajanus conducted his first orchestral work, elegy (1909) for strings, in January 1910. The work was favourably received and was given four further performances in Helsinki that spring. It is a melodically charming and harmonically nuanced miniature that betrays the influence of Tchaikovsky in its achingly tender tones. Later, Madetoja incorporated Elegia into his four-movement Sinfoninen sarja (Symphonic Suite, 1910), but even so it is better known as a separate number. -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

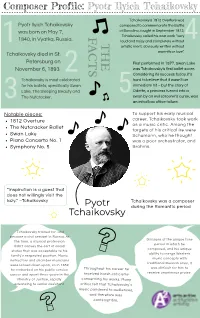

Download This Composer Profile Here

Composer Profile: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed to commemorate the Battle was born on May 7, of Borodino, fought in September 1812, F Tchaikovsky called his own work “very 1840, in Vyatka, Russia. loud and noisy and completely without THE A 4 1 artistic merit, obviously written without Tchaikovsky died in St. CTS warmth or love”. Petersburg on First performed in 1877, Swan Lake November 6, 1893. was Tchaikovsky’s first ballet score. 2 Considering its success today, it's Tchaikovsky is most celebrated hard to believe that it wasn’t an for his ballets, specifically Swan immediate hit – but the story of Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and Odette, a princess turned into a The Nutcracker. 5 swan by an evil sorcerer's curse, was 3 an initial box office failure. Notable pieces: To support his early musical 1812 Overture career, Tchaikovsky took work as a music critic. Among the The Nutcracker Ballet targets of his critical ire were Swan Lake Schumann, who he thought Piano Concerto No. 1 was a poor orchestrator, and Symphony No. 5 Brahms. “Inspiration is a guest that does not willingly visit the lazy.” –Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky was a composer I'mPy oOtrne! during the Romantic period Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky trained for, and became a civil servant in Russia. At Because of the unique time the time, a musical profession period in which he didn’t convey the sort of social composed, and his unique status that was acceptable to his ability to merge Western family’s respected position. Music music concepts with instructors and chamber musicians traditional Russian ones, it were looked down upon, so in 1859 was difficult for him to he embarked on his public service Throughout his career he receive unanimous praise. -

Edition 3 | 2019-2020

A Message from the Chair of the Board of Trustees 4 2020 Musician Roster 5 JANUARY 10-12 9 Russian Winter Festival I: Natasha Returns JANUARY 24-25 17 Russian Winter Festival II: Masterpieces FEBRUARY 21-22 25 Saint-Saëns Organ Symphony With Cameron Carpenter FEBRUARY 28-29 33 Chihuly Festival: Bluebeard’s Castle Spotlight on Education 42 Board of Trustees/Staff 43 Friends of the Columbus Symphony 45 Columbus Symphony League 46 Future Inspired 47 Partners in Excellence 49 Corporate and Foundation Partners 49 Individual Partners 50 In Kind 53 Tribute Gifts 53 Legacy Society 56 Concert Hall & Ticket Information 58 ADVERTISING Onstage Publications 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 e-mail: [email protected] www.onstagepublications.com The Columbus Symphony program is published in association with Onstage Publications, 1612 Prosser Avenue, Dayton, Ohio 45409. The Columbus Symphony program may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher. Onstage Publications is a division of Just Business!, Inc. Contents © 2020. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Dear Columbus Symphony Supporter, As the wonderful performances of our 2019-20 season continue, we again thank you for your support of quality, live performances of orchestral music in our community! We start the new year by putting the star in Columbus with Russian Winter Festival I: Natasha Returns (January 10–12, Ohio Theatre). Natasha Paremski performs Rachmaninoff’s first piano concerto, and the concert concludes with the dramatic genius of Tchaikovsky in his powerful Manfred symphony. -

03 May 2021.Pdf

3 May 2021 12:01 AM Francesco Geminiani (1687-1762) Concerto grosso in D minor, Op 7 No 2 La Petite Bande, Sigiswald Kuijken (conductor) DEWDR 12:10 AM Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) Prelude for guitar no.1 in E minor Norbert Kraft (guitar) CACBC 12:15 AM Sergey Rachmaninov (1873-1943) 2 Songs: When Night Descends in silence; Oh stop thy singing maiden fair Fredrik Zetterstrom (baritone), Tobias Ringborg (violin), Anders Kilstrom (piano) SESR 12:24 AM Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) Serenade no 2 in G minor for violin & orchestra, Op 69b Judy Kang (violin), Orchestre Symphonique de Laval CACBC 12:33 AM Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Polonaise No.2 in E major from (S.223) Ferruccio Busoni (piano) SESR 12:43 AM Giovanni Gabrieli (1557-1612) Exaudi me, for 12 part triple chorus, continuo and 4 trombones Danish National Radio Chorus, Copenhagen Cornetts & Sackbutts, Lars Baunkilde (violone), Soren Christian Vestergaard (organ), Bo Holten (conductor) DKDR 12:50 AM Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Symphony no 104 in D major "London" (H.1.104) Tamas Vasary (conductor), Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra HUMR 01:15 AM Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957) Piano Quintet in E major, Op 15 Daniel Bard (violin), Tim Crawford (violin), Mark Holloway (viola), Chiara Enderle (cello), Paolo Giacometti (piano) CHSRF 01:47 AM Barbara Strozzi (1619-1677) "Hor che Apollo" - Serenade for Soprano, 2 violins & continuo Susanne Ryden (soprano), Musica Fiorita, Daniela Dolci (director) DEWDR 02:01 AM Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Ma mère l'oye (suite) WDR Radio Orchestra, Cologne, Christoph Eschenbach (conductor) DEWDR 02:18 AM Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) Concerto for Two Pianos in D minor, FP 61 Lucas Jussen (piano), Arthur Jussen (piano), WDR Radio Orchestra, Cologne, Christoph Eschenbach (conductor) DEWDR 02:38 AM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Symphony No. -

Tchaikovsky.Pdf

Tchaikovsky CD 1 1 Orchestrion It wasn’t unusual, in the middle of the 19th century, to hear sounds like that coming from the drawing rooms of comfortable, middle-class families. The Orchestrion, one of the first and grandest of mass-produced mechanical music-makers, was one of the precursors of the 20th century gramophone. It brought music into homes where otherwise it might never have been heard, except through the stumbling fingers of children, enduring, or in some cases actually enjoying, their obligatory half-hour of practice time. In most families the Orchestrion was a source of pleasure. But in one Russian household, it seems to have been rather more. It afforded a small boy named Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky some of his earliest glimpses into a world, and a language, which was to become (in more senses then one), his lifeline. One evening his French governess, Fanny Dürbach, went into the nursery and found the tiny child sitting up in bed, crying. ‘What’s the matter?’ she asked – and his answer surprised her. ‘This music’ he wailed, ‘this music!’ She listened. The house was quiet. ‘No. It’s here,’ cried the boy – he pointed to his head. ‘It’s here, and I can’t make it go away. It won’t leave me.’ And of course it never did. ‘His sensitivity knew no bounds and so one had to deal with him very carefully. Every little trifle could upset or wound him. He was a child of glass. As for reproofs and admonitions (with him there could be no question of punishments), what would have been water off a duck’s back to other children affected him deeply, and if the degree of severity was increased only the slightest, it would upset him alarmingly.’ Despite his outwardly happy appearance, peace of mind is something Tchaikovsky rarely knew, from childhood to his dying day. -

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER the CANOPY of MY LIFE Artistic, Creative, Musical Pedagogy, Public and Private

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER THE CANOPY OF MY LIFE Artistic, creative, musical pedagogy, public and private Translated by John Ranck But1 you are getting old, pick Flowers, growing on the graves And with them renew your heart. Nekrasov2 And ethereally brightening-within-me Beloved shadows arose in the Argentine mist Balmont3 The Tcherepnins are from the vicinity of Izborsk, an ancient Russian town in the Pskov province. If I remember correctly, my aged aunts lived on an estate there which had been passed down to them by their fathers and grandfathers. Our lineage is not of the old aristocracy, and judging by excerpts from the book of Records of the Nobility of the Pskov province, the first mention of the family appears only in the early 19th century. I was born on May 3, 1873 in St. Petersburg. My father, a doctor, was lively and very gifted. His large practice drew from all social strata and included literary luminaries with whom he collaborated as medical consultant for the gazette, “The Voice” that was published by Kraevsky.4 Some of the leading writers and poets of the day were among its editors. It was my father’s sorrowful duty to serve as Dostoevsky’s doctor during the writer’s last illness. Social activities also played a large role in my father’s life. He was an active participant in various medical societies and frequently served as chairman. He also counted among his patients several leading musical and theatrical figures. My father was introduced to the “Mussorgsky cult” at the hospitable “Tuesdays” that were hosted by his colleague, Dr. -

Iolanta Bluebeard's Castle

iolantaPETER TCHAIKOVSKY AND bluebeard’sBÉLA BARTÓK castle conductor Iolanta Valery Gergiev Lyric opera in one act production Libretto by Modest Tchaikovsky, Mariusz Treliński based on the play King René’s Daughter set designer by Henrik Hertz Boris Kudlička costume designer Bluebeard’s Castle Marek Adamski Opera in one act lighting designer Marc Heinz Libretto by Béla Balázs, after a fairy tale by Charles Perrault choreographer Tomasz Wygoda Saturday, February 14, 2015 video projection designer 12:30–3:45 PM Bartek Macias sound designer New Production Mark Grey dramaturg The productions of Iolanta and Bluebeard’s Castle Piotr Gruszczyński were made possible by a generous gift from Ambassador and Mrs. Nicholas F. Taubman general manager Peter Gelb Additional funding was received from Mrs. Veronica Atkins; Dr. Magdalena Berenyi, in memory of Dr. Kalman Berenyi; music director and the National Endowment for the Arts James Levine principal conductor Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera and Fabio Luisi Teatr Wielki–Polish National Opera The 5th Metropolitan Opera performance of PETER TCHAIKOVSKY’S This performance iolanta is being broadcast live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera International Radio Network, sponsored conductor by Toll Brothers, Valery Gergiev America’s luxury in order of vocal appearance homebuilder®, with generous long-term marta duke robert support from Mzia Nioradze Aleksei Markov The Annenberg iol anta vaudémont Foundation, The Anna Netrebko Piotr Beczala Neubauer Family Foundation, the brigit te Vincent A. Stabile Katherine Whyte Endowment for Broadcast Media, l aur a and contributions Cassandra Zoé Velasco from listeners bertr and worldwide. Matt Boehler There is no alméric Toll Brothers– Keith Jameson Metropolitan Opera Quiz in List Hall today. -

Chicago Presents Symphony Muti Symphony Center

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI zell music director SYMPHONY CENTER PRESENTS 17 cso.org1 312-294-30008 1 STIRRING welcome I have always believed that the arts embody our civilization’s highest ideals and have the power to change society. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is a leading example of this, for while it is made of the world’s most talented and experienced musicians— PERFORMANCES. each individually skilled in his or her instrument—we achieve the greatest impact working together as one: as an orchestra or, in other words, as a community. Our purpose is to create the utmost form of artistic expression and in so doing, to serve as an example of what we can achieve as a collective when guided by our principles. Your presence is vital to supporting that process as well as building a vibrant future for this great cultural institution. With that in mind, I invite you to deepen your relationship with THE music and with the CSO during the 2017/18 season. SOUL-RENEWING Riccardo Muti POWER table of contents 4 season highlight 36 Symphony Center Presents Series Riccardo Muti & the Chicago Symphony Orchestra OF MUSIC. 36 Chamber Music 8 season highlight 37 Visiting Orchestras Dazzling Stars 38 Piano 44 Jazz 10 season highlight Symphonic Masterworks 40 MusicNOW 20th anniversary season 12 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Series 41 season highlight 34 CSO at Wheaton College John Williams Returns 41 CSO at the Movies Holiday Concerts 42 CSO Family Matinees/Once Upon a Symphony® 43 Special Concerts 13 season highlight 44 Muti Conducts Rossini Stabat mater 47 CSO Media and Sponsors 17 season highlight Bernstein at 100 24 How to Renew Guide center insert 19 season highlight 24 Season Grid & Calendar center fold-out A Tchaikovsky Celebration 23 season highlight Mahler 5 & 9 24 season highlight Symphony Ball NIGHT 27 season highlight Riccardo Muti & Yo-Yo Ma 29 season highlight AFTER The CSO’s Own 35 season highlight NIGHT. -

You Conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in Their Annual Ball at the Musikverein, the Day Before Yesterday

Interview with conductor Semyon Bychkov Tutti-magazine: You conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in their annual ball at the Musikverein, the day before yesterday. What did you take away from the experience ? Semyon Bychkov: It was an extraordinary experience, it is hard to find words to describe it. The women and the debutantes were dressed in sumptuous ball gowns and the atmosphere made it feel as if one were in the 19th century. For someone like me who sometimes wishes they’d lived in the 18th or 19th centuries, the evening reminded me of a style approrpriate to a particularly beautiful past. As I’ve said many times to your colleagues, I would be very happy if this beautiful and joyful spirit could be shared by as many people as possible and offer an alternative to the vulgarity and violence which occur daily in the world today. As I was leaving on tour with the Vienna Philharmonic, I arrived to drop my things off at the Great Hall of the Musikverein in the afternoon – the following day we would be playing in Hamburg at the Elbphilharmonie - the Hall was deserted and the view was so extraordinary that I couldn’t resist taking some photographs : all the stalls seats had been removed and replaced by flowers and tables. Of course I also noticed the wall covered with photographs of conductors who had worked with the orchestra, and thought: «So here is the conductors’ wall of fame»… That evening, immediately after our concert, everything that had been installed was moved to the large empty space under the floor of the Hall.