CC-130 Art 77.Pdf (832.8Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja the ZOOSEMIOTICS of SOCIALIZATION

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja THE ZOOSEMIOTICS OF SOCIALIZATION: CASE-STUDY IN SOCIALIZING RED FOX (VULPES VULPES) IN TANGEN ANIMAL PARK, NORWAY Master’s Thesis Supervisors: Timo Maran, Ph.D Nelly Mäekivi, M.A Tartu 2014 CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….4 1. The theoretical aspects of keeping wild animals in captivity ………………………………7 1.1. The main arguments on the ethics of keeping animals in captivity……………….7 1.2. Modern viewpoints on animal welfare……………………………………………9 1.3. Modern viewpoints on animal behaviour………………………………………..13 1.3.1. Behavioural display and animal welfare……………………………….14 1.4. The role of enrichment in animal welfare………………………………………..17 1.4.1. The essence of animal training in zoos………………………………...19 1.5. The importance of human-animal relationships in the zoo………………………21 1.5.1. The importance of Umwelt consideration……………………………...23 1.5.1.1. The functional circle ………………………………………...24 1.5.2. The effect of zoo visitors on animal welfare…………………………..26 1.5.3. The effect of keeper-animal relationships on animal welfare………….28 1.6. Explaining animal communication…………………………………………........30 1.7. Socialization – a method of improving welfare of captive animals……………...36 1.7.1. The need for socialization……………………………………………...37 1.7.2. The basic mechanisms of socialization………………………………...38 2. The research methodology of a zoosemiotic approach to socialization …………………...40 2.1. Thick description of socialization………………………………………………..40 2.2. Actor-orientedness of the research……………………………………………….42 2.3. Participatory observation………………………………………………………...43 2.4. The dimensions of interpretations presented in the thesis ………………………44 3. Case-study of the socialization of Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)………………………………46 3.1. General methods of socialization………………………………………………..46 3.1.1. -

Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us About Human Language?

Linguistic Frontiers • 1(1) • 14-38 • 2018 DOI: 10.2478/lf-2018-0005 Linguistic Frontiers Representational Systems in Zoosemiotics and Anthroposemiotics Part I: What Have the So- Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us about Human Language? Research Article Vilém Uhlíř* Theoretical and Evolutionary Biology, Department of Philosophy and History of Sciences. Charles University. Viničná 7, 12843 Praha 2, Czech Republic Received ???, 2018; Accepted ???, 2018 Abstract: This paper offers a brief critical review of some of the so-called “Talking Animals” projects. The findings from the projects are compared with linguistic data from Homo sapiens and with newer evidence gleaned from experiments on animal syntactic skills. The question concerning what had the so-called “Talking Animals” really done is broken down into two categories – words and (recursive) syntax. The (relative) failure of the animal projects in both categories points mainly to the fact that the core feature of language – hierarchical recursive syntax – is missing in the pseudo-linguistic feats of the animals. Keywords: language • syntax • representation • meta-representation • zoosemiotics • anthroposemiotics • talking animals • general cognition • representational systems • evolutionary discontinuity • biosemiotics © Sciendo 1. The “Talking Animals” Projects For the sake of brevity, I offer a greatly selective review of some of the more important “Talking Animals” projects. Please note that many omissions were necessary for reasons of space. The “thought climate” of the 1960s and 1970s was formed largely by the Skinnerian zeitgeist, in which it seemed possible to teach any animal to master any, or almost any, skill, including language. Perhaps riding on an ideological wave, following the surprising claims of Fossey [1] and Goodall [2] concerning primates, as well as the claims of Lilly [3] and Batteau and Markey [4] concerning dolphins, many scientists and researchers focussed on the continuities between humans and other species, while largely ignoring the discontinuities and differences. -

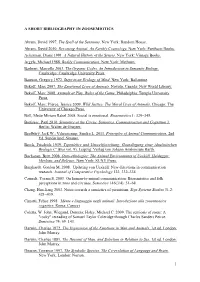

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

Thomas A. Sebeok and Biology: Building Biosemiotics

Cybernetics And Human Knowing. Vol. 10, no. 1, pp. xx-xx Thomas A. Sebeok and biology: Building biosemiotics Kalevi Kull1 Abstract: The paper attempts to review the impact of Thomas A. Sebeok (1920–2001) on biosemiotics, or semiotic biology, including both his work as a theoretician in the field and his activity in organising, publishing, and communicating. The major points of his work in the field of biosemiotics concern the establishing of zoosemiotics, interpretation and development of Jakob v. Uexküll’s and Heini Hediger’s ideas, typological and comparative study of semiotic phenomena in living organisms, evolution of semiosis, the coincidence of semiosphere and biosphere, research on the history of biosemiotics. Keywords: semiotic biology, zoosemiotics, endosemiotics, biosemiotic paradigm, semiosphere, biocommunication, theoretical biology “Culture,” so-called, is implanted in nature; the environment, or Umwelt, is a model generated by the organism. Semiosis links them. T. A. Sebeok (2001c, p. vii) When an organic body is dead, it does not carry images any more. This is a general feature that distinguishes complex forms of life from non-life. The images of the organism and of its images, however, can be carried then by other, living bodies. The images are singular categories, which means that they are individual in principle. The identity of organic images cannot be of mathematical type, because it is based on the recognition of similar forms and not on the sameness. The organic identity is, therefore, again categorical, i.e., singular. Thus, in order to understand the nature of images, we need to know what life is, we need biology — a biology that can deal with phenomena of representation, recognition, categorisation, communication, and meaning. -

Sebeok As a Semiotician Semiotics and Its Masters (Past and Present) Session Prof

Southeast European Center for Semiotic Studies. Sofia 2014, 16–20 September, New Bulgarian University, Montevideo 21, Sofia 1618, Bulgaria http://semio2014.org/en/home; http://semio2014.org/en/sebeok-as-a-semiotician Thursday, 16 September 2014, 14:00–19:00 h Sebeok as a semiotician Semiotics and its Masters (past and present) session prof. emeritus VILMOS VOIGT ([email protected]) Thomas A. Sebeok (Budapest 9 November 1920 – Bloomington 21 December 2001) There should be a discussion on the major topic and results of Sebeok’s semiotic activity. He started as a Finno-Ugrist linguist, and then moved to general linguistics and communication theory and non-verbal communication. Then he became an outliner and historiographer of semiotics, the founding father of “zoosemiotics”, and of a classical style “biosemiotics”. He did more than anybody else for international congresses, teaching and publication of worldwide semiotics. He was a central knot of the “semiotic web”. There are still many persons who have known and remember him. Abstracts: 1) EERO TARASTI , University of Helsinki, President of the IASS/AIS (([email protected]) The Sebeokian Vision of Semiotics. From Finno-Ugrian Studies via Zoosemiotics to Bio- and Global Semiotics 2) Hongbing Yu, Nanjing Normal Univeristy, Nanjing, China ([email protected]) The Sebeokian Synthesis of Two Seemingly Contrary Traditions—Viewed from China The prevailing dominance of Peircean studies of signs in the West, the witness of which is manifestly borne by a 1988 paper entitled “Why we prefer Peirce to Saussure” written by one of the major contemporary scholars on Peirce, T.L. Short, has been well-acknowledged in the domain Chinese semiotics. -

Modeling, Dialogue, and Globality: Biosemiotics and Semiotics of Self. 2

Sign Systems Studies 31.1, 2003 Modeling, dialogue, and globality: Biosemiotics and semiotics of self. 2. Biosemiotics, semiotics of self, and semioethics Susan Petrilli Dept. of Linguistic Practices and Text Analysis, University of Bari Via Garruba 6, 70100 Bari, Italy e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The main approaches to semiotic inquiry today contradict the idea of the individual as a separate and self-sufficient entity. The body of an organism in the micro- and macrocosm is not an isolated biological entity, it does not belong to the individual, it is not a separate and self-sufficient sphere in itself. The body is an organism that lives in relation to other bodies, it is intercorporeal and interdependent. This concept of the body finds confir- mation in cultural practices and worldviews based on intercorporeity, inter- dependency, exposition and opening, though nowadays such practices are almost extinct. An approach to semiotics that is global and at once capable of surpassing the illusory idea of definitive and ultimate boundaries to identity presupposes dialogue and otherness. Otherness obliges identity to question the tendency to totalizing closure and to reorganize itself always anew in a process related to ‘infinity’, as Emmanuel Levinas teaches us, or to ‘infinite semiosis’, to say it with Charles Sanders Peirce. Another topic of this paper is the interrelation in anthroposemiosis between man and machine and the implications involved for the future of humanity. Our overall purpose is to develop global semiotics in the direction of “semioethics”, as proposed by S. Petrilli and A. Ponzio and their ongoing research. -

Animal Umwelten in a Changing World

Tartu Semiotics Library 18 Tartu Tartu Semiotics Library 18 Animal umwelten in a changing world: Zoosemiotic perspectives represents a clear and concise review of zoosemiotics, present- ing theories, models and methods, and providing interesting examples of human–animal interactions. The reader is invited to explore the umwelten of animals in a successful attempt to retrieve the relationship of people with animals: a cornerstone of the past common evolutionary processes. The twelve chapters, which cover recent developments in zoosemiotics and much more, inspire the reader to think about the human condition and about ways to recover our lost contact with the animal world. Written in a clear, concise style, this collection of articles creates a wonderful bridge between Timo Maran, Morten Tønnessen, human and animal worlds. It represents a holistic approach Kristin Armstrong Oma, rich with suggestions for how to educate people to face the dynamic relationships with nature within the conceptual Laura Kiiroja, Riin Magnus, framework of the umwelt, providing stimulus and opportuni- Nelly Mäekivi, Silver Rattasepp, ties to develop new studies in zoosemiotics. Professor Almo Farina, CHANGING WORLD A IN UMWELTEN ANIMAL Paul Thibault, Kadri Tüür University of Urbino “Carlo Bo” This important book offers the first coherent gathering of perspectives on the way animals are communicating with each ANIMAL UMWELTEN other and with us as environmental change requires increasing adaptation. Produced by a young generation of zoosemiotics scholars engaged in international research programs at Tartu, IN A CHANGING this work introduces an exciting research field linking the biological sciences with the humanities. Its key premises are that all animals participate in a dynamic web of meanings WORLD: and signs in their own distinctive styles, and all animal spe- cies have distinctive cultures. -

Handbook-Of-Semiotics.Pdf

Page i Handbook of Semiotics Page ii Advances in Semiotics THOMAS A. SEBEOK, GENERAL EDITOR Page iii Handbook of Semiotics Winfried Nöth Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis Page iv First Paperback Edition 1995 This Englishlanguage edition is the enlarged and completely revised version of a work by Winfried Nöth originally published as Handbuch der Semiotik in 1985 by J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart. ©1990 by Winfried Nöth All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Nöth, Winfried. [Handbuch der Semiotik. English] Handbook of semiotics / Winfried Nöth. p. cm.—(Advances in semiotics) Enlarged translation of: Handbuch der Semiotik. Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. ISBN 0253341205 1. Semiotics—handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Communication —Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title. II. Series. P99.N6513 1990 302.2—dc20 8945199 ISBN 0253209595 (pbk.) CIP 4 5 6 00 99 98 Page v CONTENTS Preface ix Introduction 3 I. History and Classics of Modern Semiotics History of Semiotics 11 Peirce 39 Morris 48 Saussure 56 Hjelmslev 64 Jakobson 74 II. Sign and Meaning Sign 79 Meaning, Sense, and Reference 92 Semantics and Semiotics 103 Typology of Signs: Sign, Signal, Index 107 Symbol 115 Icon and Iconicity 121 Metaphor 128 Information 134 Page vi III. -

Bio 314 Animal Behv Bio314new

NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA SCHOOL OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COURSE CODE: BIO 314: COURSE TITLE: ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR xii i BIO 314: ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR Course Writers/Developers Miss Olakolu Fisayo Christie Nigerian Institute for Oceanography and Marine Research, No 3 Wilmot Point Road, Bar-beach Bus-stop, Victoria Island, Lagos, Nigeria. Course Editor: Dr. Adesina Adefunke Ministry of Health, Alausa. Lagos NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA xii i BIO 314 COURSE GUIDE Introduction Animal Behaviour (314) is a second semester course. It is a two credit units compustory course which all students offering Bachelor of Science (BSc) in Biology must take. This course deals with the theories and principles of adaptive behaviour and evolution of animals. The course contents are history of ethology. Reflex and complex behaviour. Orientation and taxes. Fixed action patterns, releasers, motivation and driver. Displays, displacement activities and conflict behaviour. Learning communication and social behaviour. The social behaviour of primates. Hierarchical organization. The physiology of behaviour. Habitat selection, homing and navigation. Courtship and parenthood. Biological clocks. What you will learn in this course In this course, you have the course units and a course guide. The course guide will tell you briefly what the course is all about. It is a general overview of the course materials you will be using and how to use those materials. It also helps you to allocate the appropriate time to each unit so that you can successfully complete the course within the stipulated time limit. The course guide also helps you to know how to go about your Tutor-Marked-Assignment which will form part of your overall assessment at the end of the course. -

A Critical Companion to Zoosemiotics BIOSEMIOTICS

A Critical Companion to Zoosemiotics BIOSEMIOTICS VOLUME 5 Series Editors Marcello Barbieri Professor of Embryology University of Ferrara, Italy President Italian Association for Theoretical Biology Editor-in-Chief Biosemiotics Jesper Hoffmeyer Associate Professor in Biochemistry University of Copenhagen President International Society for Biosemiotic Studies Aims and Scope of the Series Combining research approaches from biology, philosophy and linguistics, the emerging field of biosemi- otics proposes that animals, plants and single cells all engage insemiosis – the conversion of physical signals into conventional signs. This has important implications and applications for issues ranging from natural selection to animal behaviour and human psychology, leaving biosemiotics at the cutting edge of the research on the fundamentals of life. The Springer book series Biosemiotics draws together contributions from leading players in international biosemiotics, producing an unparalleled series that will appeal to all those interested in the origins and evolution of life, including molecular and evolutionary biologists, ecologists, anthropologists, psychol- ogists, philosophers and historians of science, linguists, semioticians and researchers in artificial life, information theory and communication technology. For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/7710 Dario Martinelli A Critical Companion to Zoosemiotics People, Paths, Ideas 123 Dario Martinelli University of Helsinki Institute of Art Research Faculty of Arts PL 35 (Vironkatu 1) -

Neglected Aspects of Peirce's Writings

Neglected Aspects of Peirce’s Writings: Contributions to Ethics and Humanism Susan Petrilli 1. New Perspectives reading Peirce; 2. Otherness in the self. The responsive interpretant, significance and value; 3. From reason to reasonableness; 4. Self between love and logic, reading together Peirce, Welby, Levinas; 5. Cosmology, semiotics and logic; 6. Enter semioethics 1. New perspectives reading Peirce Certain aspects of Charles S. Peirce’s philosophical and semiotic conception have been generally neglected or misunderstood. In particular, my reference is to such aspects as the following: the question of the relation between semiosis, interpretation and quasi-interpreter; the impossibility of separating knowledge from responsible awareness, that is, knowledge from responsibility; the interconnection between body and sign; the dialogic nature of the sign and of the self; the relation to the sign to otherness; the foundation of anthropology and cosmology on agapastic relations; the critique of a monadic and egotistic conception of the social with reference to capitalist society and liberal ideology at the time Peirce was researching and writing; Peircean metaphysics as an instance of transcendence of the actual being of human beings, that is, transcendence of what they know and what they do. In other words, Peirce not only thematizes the actual being of human beings in gnoseological terms, but beyond this also in ethical terms; the idea of inferential procedure by approximation, not only when a question of the cognitive object but also for what concerns a more congruous social system, that is, for a system more 235 Neglected Aspects of Peirce’s Writings responsive to human capacities and aspirations; opposition between “reasonableness” and “reason”, more specifically between “reasonableness” which does not separate logic from ethics, on the one hand, and “reason” when it tends to be absolute and dogmatic, on the other; Peirce’s unconditional refusal of pragmatism founded on the notion of utility and practice thereof. -

Download Article (PDF)

2013 · Volume 196 · NUMBeR 1/4 Semiotica Journal of the International Association for Semiotic Studies / Revue de l’Association Internationale de Sémiotique Special issue On and beyOnd significs: centennial issue fOr VictOria lady Welby (1837–1912) editoR-iN-chief/ Book ReView editors/ RédacteuR-eN-chef compteS ReNduS Marcel Danesi Paul Perron Program in Semiotics and (Coordinator/Coordinateur) Communication Theory E-mail: [email protected] Victoria College Paul Colilli University of Toronto Claudio Guerri Toronto, Ontario M5S 1K7 Frederik Stjernfelt Canada Kim Sung-do Phone (416) 585-4412 E-mail: [email protected] cooRdiNators/ cooRdiNatRiceS Associate editoR/ Caterina Clivio RédacteuR adjoiNt Vanessa Compagnone Stéphanie Walsh-Matthews Stacy Costa E-mail: [email protected] Alison Mann AssiStaNt editoR/ AssiStaNt à la RédactioN Paolo Ammirante E-mail: [email protected] editoRial committee/ comité de RédactioN Myrdene Anderson Prisca Augustyn Paolo Balboni Marcello Barbieri Arthur Asa Berger Mohamed Bernoussi Per Aage Brandt Patrizia Calefato Le Cheng Paul Cobley John Deely Umberto Eco Robbie B. H. Goh André Helbo Anne-Marie Houdebine Kalevi Kull Solomon Marcus Dragana Martinovic Frank Nuessel Jerzy Pelc Susan Petrilli Roland Posner Eddo Rigotti Andrea Rocci Shi-xu Eero Tarasti Bill Thompson Giovanna Zaganelli Yiheng Zhao iNTERNATIONAL aSSOCIATION FOR SEMIOTIC STUDIES Officers Of the assOciatiOn PreSideNt Eero Tarasti, Finland [email protected] hoNoRaRy PreSideNtS Umberto Eco, Italy Jerzy Pelc, Poland Roland