Modeling, Dialogue, and Globality: Biosemiotics and Semiotics of Self. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja the ZOOSEMIOTICS of SOCIALIZATION

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja THE ZOOSEMIOTICS OF SOCIALIZATION: CASE-STUDY IN SOCIALIZING RED FOX (VULPES VULPES) IN TANGEN ANIMAL PARK, NORWAY Master’s Thesis Supervisors: Timo Maran, Ph.D Nelly Mäekivi, M.A Tartu 2014 CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….4 1. The theoretical aspects of keeping wild animals in captivity ………………………………7 1.1. The main arguments on the ethics of keeping animals in captivity……………….7 1.2. Modern viewpoints on animal welfare……………………………………………9 1.3. Modern viewpoints on animal behaviour………………………………………..13 1.3.1. Behavioural display and animal welfare……………………………….14 1.4. The role of enrichment in animal welfare………………………………………..17 1.4.1. The essence of animal training in zoos………………………………...19 1.5. The importance of human-animal relationships in the zoo………………………21 1.5.1. The importance of Umwelt consideration……………………………...23 1.5.1.1. The functional circle ………………………………………...24 1.5.2. The effect of zoo visitors on animal welfare…………………………..26 1.5.3. The effect of keeper-animal relationships on animal welfare………….28 1.6. Explaining animal communication…………………………………………........30 1.7. Socialization – a method of improving welfare of captive animals……………...36 1.7.1. The need for socialization……………………………………………...37 1.7.2. The basic mechanisms of socialization………………………………...38 2. The research methodology of a zoosemiotic approach to socialization …………………...40 2.1. Thick description of socialization………………………………………………..40 2.2. Actor-orientedness of the research……………………………………………….42 2.3. Participatory observation………………………………………………………...43 2.4. The dimensions of interpretations presented in the thesis ………………………44 3. Case-study of the socialization of Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)………………………………46 3.1. General methods of socialization………………………………………………..46 3.1.1. -

Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us About Human Language?

Linguistic Frontiers • 1(1) • 14-38 • 2018 DOI: 10.2478/lf-2018-0005 Linguistic Frontiers Representational Systems in Zoosemiotics and Anthroposemiotics Part I: What Have the So- Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us about Human Language? Research Article Vilém Uhlíř* Theoretical and Evolutionary Biology, Department of Philosophy and History of Sciences. Charles University. Viničná 7, 12843 Praha 2, Czech Republic Received ???, 2018; Accepted ???, 2018 Abstract: This paper offers a brief critical review of some of the so-called “Talking Animals” projects. The findings from the projects are compared with linguistic data from Homo sapiens and with newer evidence gleaned from experiments on animal syntactic skills. The question concerning what had the so-called “Talking Animals” really done is broken down into two categories – words and (recursive) syntax. The (relative) failure of the animal projects in both categories points mainly to the fact that the core feature of language – hierarchical recursive syntax – is missing in the pseudo-linguistic feats of the animals. Keywords: language • syntax • representation • meta-representation • zoosemiotics • anthroposemiotics • talking animals • general cognition • representational systems • evolutionary discontinuity • biosemiotics © Sciendo 1. The “Talking Animals” Projects For the sake of brevity, I offer a greatly selective review of some of the more important “Talking Animals” projects. Please note that many omissions were necessary for reasons of space. The “thought climate” of the 1960s and 1970s was formed largely by the Skinnerian zeitgeist, in which it seemed possible to teach any animal to master any, or almost any, skill, including language. Perhaps riding on an ideological wave, following the surprising claims of Fossey [1] and Goodall [2] concerning primates, as well as the claims of Lilly [3] and Batteau and Markey [4] concerning dolphins, many scientists and researchers focussed on the continuities between humans and other species, while largely ignoring the discontinuities and differences. -

Encoding/Decoding, the Transmission Model and a Court of Law

Final Revision: Title: Encoding/Decoding, the Transmission Model and a Court of Law Keyan G. Tomaselli Abstract: Stuart Hall’s encoding/decoding model is discussed in terms of CS Peirce’s theory of the interpreter and interpretant. This historical semiotic window frames an example to which the Hall model was applied in South Africa to oppose a military dirty tricks campaign that involved a Supreme Court case brought against the Minister of Defence by the End Conscription Campaign (ECC) requiring him to cease his disinformation against the ECC. The Minister’s own expert had proposed a transmission model of communication that was defeated by the Peirce-Hall combination. The author argues that the model can be massively strengthened when combined with Peirceian semiotics. Keywords: Stuart Hall, encoding/decoding, CS Peirce, Phaneroscopy, semiotics, reception Media-society relations are best studied within the broader conceptual environment facilitated by the circuit of culture model (Du Gay et al., 1997) that mimics Karl Marx’s circle of capitalist production, distribution and exchange. The model implicitly incorporated Stuart Hall’s (1981) ground-breaking encoding-decoding relationship. My argument will be that Charles Sanders Peirce’s (Hartshorne and Weiss, 1931-5) idea of the ‘interpretant’ – the idea to which the sign gives rise - was a crucial, if unspoken, progenitor of Hall’s model. Working at the same time as Hall, Umberto Eco (1972) had proposed “aberrant decoding” on which Hall must have drawn, as his chapter refers to a semiological article on encoding. The early Stencilled Occasional Paper and Hutchinson book series’ that mapped out the early Birmingham University Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) project under Stuart Hall’s leadership identified the following semiological/semiotic sources also: Roland Barthes, Jonathan Culler and V.I. -

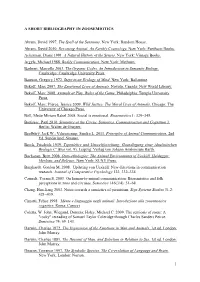

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

Hypertext Semiotics in the Commercialized Internet

Hypertext Semiotics in the Commercialized Internet Moritz Neumüller Wien, Oktober 2001 DOKTORAT DER SOZIAL- UND WIRTSCHAFTSWISSENSCHAFTEN 1. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Wolfgang Panny, Institut für Informationsver- arbeitung und Informationswirtschaft der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien, Abteilung für Angewandte Informatik. 2. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dr. Herbert Hrachovec, Institut für Philosophie der Universität Wien. Betreuer: Gastprofessor Univ. Doz. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Veith Risak Eingereicht am: Hypertext Semiotics in the Commercialized Internet Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Sozial- und Wirtschaftswissenschaften an der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien eingereicht bei 1. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Panny, Institut für Informationsverarbeitung und Informationswirtschaft der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien, Abteilung für Angewandte Informatik 2. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dr. Herbert Hrachovec, Institut für Philosophie der Universität Wien Betreuer: Gastprofessor Univ. Doz. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Veith Risak Fachgebiet: Informationswirtschaft von MMag. Moritz Neumüller Wien, im Oktober 2001 Ich versichere: 1. daß ich die Dissertation selbständig verfaßt, andere als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel nicht benutzt und mich auch sonst keiner unerlaubten Hilfe bedient habe. 2. daß ich diese Dissertation bisher weder im In- noch im Ausland (einer Beurteilerin / einem Beurteiler zur Begutachtung) in irgendeiner Form als Prüfungsarbeit vorgelegt habe. 3. daß dieses Exemplar mit der beurteilten Arbeit überein -

Augusto Ponzio the Dialogic Nature of Signs “Semiotics Institute on Line” 8 Lectures for the “Semiotics Institute on Line” (Prof

Augusto Ponzio The Dialogic Nature of Signs “Semiotics Institute on Line” 8 lectures for the “Semiotics Institute on Line” (Prof. Paul Bouissac, Toronto) Translation from Italian by Susan Petrilli --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7. Dialogism and Biosemiosis Bakhtinian dialogism and biosemiosis In light of the Bakhtinian notion of ‘dialogism,’ we have observed (see first lecture) that dialogue is neither the communication of messages, nor an initiative taken by self. On the contrary, self is always in dialogue with the other, that is to say, with the world and with others, whether it knows it or not; self is always in dialogue with the word of the other. Identity is dialogic. Dialogism is at the very heart of the self. The self, ‘the semiotic self’ (see Sebeok, Petrilli, Ponzio 2001), is dialogic in the sense of a species-specifically modeled involvement with the world and with others. The self is implied dialogically in otherness, just as the ‘grotesque body’ (Bakhtin 1965) is implied in the body of other living beings. In fact, in a Bakhtinian perspective dialogue and intercorporeity are closely interconnected: there cannot be dialogue among disembodied minds, nor can dialogism be understood separately from the biosemiotic conception of sign. As we have already observed (see Ponzio 2003), we believe that Bakhtin’s main interpreters such as Holquist, Todorov, Krysinsky, and Wellek have all fundamentally misunderstood Bakhtin and his concept of dialogue. This is confirmed by their interpretation of Bakhtinian dialogue as being similar to dialogue in the terms theorized by such authors as Plato, Buber, Mukarovsky. According to Bakhtin dialogue is the embodied, intercorporeal, expression of the involvement of one’s body (which is only illusorily an individual, separate, and autonomous body) with the body of the other. -

Postmodern Test Theory

Postmodern Test Theory ____________ Robert J. Mislevy Educational Testing Service ____________ (Reprinted with permission from Transitions in Work and Learning: Implications for Assessment, 1997, by the National Academy of Sciences, Courtesy of the National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.) Postmodern Test Theory Robert J. Mislevy Good heavens! For more than forty years I have been speaking prose without knowing it. Molière, Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme INTRODUCTION Molière’s Monsieur Jourdan was astonished to learn that he had been speaking prose all his life. I know how he felt. For years I have just been doing my job— trying to improve educational assessment by applying ideas from statistics and psychology. Come to find out, I’ve been advancing “neopragmatic postmodernist test theory” without ever intending to do so. This paper tries to convey some sense of what this rather unwieldy phrase means and offers some thoughts about what it implies for educational assessment, present and future. The goods news is that we can foresee some real improvements: assessments that are more open and flexible, better connected with students’ learning, and more educationally useful. The bad news is that we must stop expecting drop-in-from-the-sky assessment to tell us, in 2 hours and for $10, the truth, plus or minus two standard errors. Gary Minda’s (1995) Postmodern Legal Movements inspired the structure of what follows. Almost every page of his book evokes parallels between issues and new directions in jurisprudence on the one hand and the debates and new developments in educational assessment on the other. Excerpts from Minda’s book frame the sections of this paper. -

Poststructuralism, Cultural Studies, and the Composition Classroom: Postmodern Theory in Practice Author(S): James A

Poststructuralism, Cultural Studies, and the Composition Classroom: Postmodern Theory in Practice Author(s): James A. Berlin Source: Rhetoric Review, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Autumn, 1992), pp. 16-33 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/465877 Accessed: 13-02-2019 19:20 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/465877?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Rhetoric Review This content downloaded from 146.111.138.234 on Wed, 13 Feb 2019 19:20:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JAMES A. BERLIN - ~~~~~~~~~~~~~Purdue University Poststructuralism, Cultural Studies, and the Composition Classroom: Postmodern Theory in Practice The uses of postmodern theory in rhetoric and composition studies have been the object of considerable abuse of late. Figures of some repute in the field-the likes of Maxine Hairston and Peter Elbow-as well as anonymous voices from the Burkean Parlor section of Rhetoric Review-most recently, TS, a graduate student, and KF, a voice speaking for "a general English teacher audience" (192)-have joined the chorus of protest. -

Media Theory and Semiotics: Key Terms and Concepts Binary

Media Theory and Semiotics: Key Terms and Concepts Binary structures and semiotic square of oppositions Many systems of meaning are based on binary structures (masculine/ feminine; black/white; natural/artificial), two contrary conceptual categories that also entail or presuppose each other. Semiotic interpretation involves exposing the culturally arbitrary nature of this binary opposition and describing the deeper consequences of this structure throughout a culture. On the semiotic square and logical square of oppositions. Code A code is a learned rule for linking signs to their meanings. The term is used in various ways in media studies and semiotics. In communication studies, a message is often described as being "encoded" from the sender and then "decoded" by the receiver. The encoding process works on multiple levels. For semiotics, a code is the framework, a learned a shared conceptual connection at work in all uses of signs (language, visual). An easy example is seeing the kinds and levels of language use in anyone's language group. "English" is a convenient fiction for all the kinds of actual versions of the language. We have formal, edited, written English (which no one speaks), colloquial, everyday, regional English (regions in the US, UK, and around the world); social contexts for styles and specialized vocabularies (work, office, sports, home); ethnic group usage hybrids, and various kinds of slang (in-group, class-based, group-based, etc.). Moving among all these is called "code-switching." We know what they mean if we belong to the learned, rule-governed, shared-code group using one of these kinds and styles of language. -

Mental Arithmetic Processes: Testing the Independence of Encoding and Calculation

Running Head: MENTAL ARITHMETIC PROCESSES 1 Mental Arithmetic Processes: Testing the Independence of Encoding and Calculation Adam R. Frampton and Thomas J. Faulkenberry Tarleton State University Author Note Adam R. Frampton and Thomas J. Faulkenberry, Department of Psychological Sciences, Tarleton State University. This research was supported in part by funding from the Tarleton State University Office of Student Research and Creative Activities. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Thomas J. Faulkenberry, Department of Psychological Sciences, Tarleton State University, Box T-0820, Stephenville, TX 76402. Phone: +1 (254) 968-9816. Email: [email protected] MENTAL ARITHMETIC PROCESSES 2 Abstract Previous work has shown that the cognitive processes involved in mental arithmetic can be decomposed into three stages: encoding, calculation, and production. Models of mental arithmetic hypothesize varying degrees of independence between these processes of encoding and calculation. In the present study, we tested whether encoding and calculation are independent by having participants complete an addition verification task. We manipulated problem size (small, large) as well as problem format, having participants verify equations presented either as Arabic digits (e.g., “3 + 7 = 10”) or using words (e.g., “three + seven = ten”). In addition, we collected trial-by-trial strategy reports. Though we found main effects of both problem size and format on response times, we found no interaction between the two factors, supporting the hypothesis that encoding and calculation function independently. However, strategy reports indicated that manipulating format caused a shift from retrieval based strategies to procedural strategies, particularly on large problems. We discuss these results in light of two competing models of mental arithmetic. -

Reading the Works of Victoria Welby and the Signific Movement

Autor: Petrilli, Susan Titel: PETRILLI: SIGNIFICS SCC HC 2 Medium: International Journal of Semiotic Law Rezensent: Wan, Marco Version: 12.04.2011 Int J Semiot Law (2013) 26:531–533 DOI 10.1007/s11196-011-9226-9 Susan Petrilli (ed): Signifying and Understanding: Reading the Works of Victoria Welby and the Signific Movement De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin, 2009, 1048 pp, ISBN: 978-3-11-021850-3 Marco Wan Published online: 12 April 2011 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 This volume seeks to restore a largely overlooked chapter in the history of semiotics, that of the life and work of Lady Victoria Welby (1837–1912) and of the Signific Movement which she founded. It does so by presenting the reader with a meticulously edited selection of passages from the entire span of Lady Welby’s writings, as well as commentaries which set these passages in their historical, cultural and intellectual contexts. Lady Welby was born into aristocratic circles in England and was a goddaughter of the Duchess of Kent, the Queen Mother. She travelled extensively with her mother, Lady Emmeline Charlotte Elizabeth, until the death of Lady Emmeline in the Syrian Desert in 1855. Together, they visited a number of countries including the United States, Canada, Mexico, Morocco, Turkey, Palestine and Syria. After her mother’s death, Lady Welby spent most of her time with the Queen Mother at her residences, and after the death of the Queen Mother she entered into the court of Queen Victoria. She was extremely well read and had an active intellectual life; amongst her many indicators of distinction were memberships to the Aristotelian Society of London, the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Sociological Society of Great Britain (of which she was a founding member). -

Thomas A. Sebeok and Biology: Building Biosemiotics

Cybernetics And Human Knowing. Vol. 10, no. 1, pp. xx-xx Thomas A. Sebeok and biology: Building biosemiotics Kalevi Kull1 Abstract: The paper attempts to review the impact of Thomas A. Sebeok (1920–2001) on biosemiotics, or semiotic biology, including both his work as a theoretician in the field and his activity in organising, publishing, and communicating. The major points of his work in the field of biosemiotics concern the establishing of zoosemiotics, interpretation and development of Jakob v. Uexküll’s and Heini Hediger’s ideas, typological and comparative study of semiotic phenomena in living organisms, evolution of semiosis, the coincidence of semiosphere and biosphere, research on the history of biosemiotics. Keywords: semiotic biology, zoosemiotics, endosemiotics, biosemiotic paradigm, semiosphere, biocommunication, theoretical biology “Culture,” so-called, is implanted in nature; the environment, or Umwelt, is a model generated by the organism. Semiosis links them. T. A. Sebeok (2001c, p. vii) When an organic body is dead, it does not carry images any more. This is a general feature that distinguishes complex forms of life from non-life. The images of the organism and of its images, however, can be carried then by other, living bodies. The images are singular categories, which means that they are individual in principle. The identity of organic images cannot be of mathematical type, because it is based on the recognition of similar forms and not on the sameness. The organic identity is, therefore, again categorical, i.e., singular. Thus, in order to understand the nature of images, we need to know what life is, we need biology — a biology that can deal with phenomena of representation, recognition, categorisation, communication, and meaning.