Sebeok As a Semiotician Semiotics and Its Masters (Past and Present) Session Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey of Semiotics Textbooks and Primers in the World

A hundred introductionsSign to semiotics, Systems Studies for a million 43(2/3), students 2015, 281–346 281 A hundred introductions to semiotics, for a million students: Survey of semiotics textbooks and primers in the world Kalevi Kull, Olga Bogdanova, Remo Gramigna, Ott Heinapuu, Eva Lepik, Kati Lindström, Riin Magnus, Rauno Thomas Moss, Maarja Ojamaa, Tanel Pern, Priit Põhjala, Katre Pärn, Kristi Raudmäe, Tiit Remm, Silvi Salupere, Ene-Reet Soovik, Renata Sõukand, Morten Tønnessen, Katre Väli Department of Semiotics University of Tartu Jakobi 2, 51014 Tartu, Estonia1 Kalevi Kull et al. Abstract. In order to estimate the current situation of teaching materials available in the fi eld of semiotics, we are providing a comparative overview and a worldwide bibliography of introductions and textbooks on general semiotics published within last 50 years, i.e. since the beginning of institutionalization of semiotics. In this category, we have found over 130 original books in 22 languages. Together with the translations of more than 20 of these titles, our bibliography includes publications in 32 languages. Comparing the authors, their theoretical backgrounds and the general frames of the discipline of semiotics in diff erent decades since the 1960s makes it possible to describe a number of predominant tendencies. In the extensive bibliography thus compiled we also include separate lists for existing lexicons and readers of semiotics as additional material not covered in the main discussion. Th e publication frequency of new titles is growing, with a certain depression having occurred in the 1980s. A leading role of French, Russian and Italian works is demonstrated. Keywords: history of semiotics, semiotics of education, literature on semiotics, teaching of semiotics 1 Correspondence should be sent to [email protected]. -

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja the ZOOSEMIOTICS of SOCIALIZATION

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja THE ZOOSEMIOTICS OF SOCIALIZATION: CASE-STUDY IN SOCIALIZING RED FOX (VULPES VULPES) IN TANGEN ANIMAL PARK, NORWAY Master’s Thesis Supervisors: Timo Maran, Ph.D Nelly Mäekivi, M.A Tartu 2014 CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….4 1. The theoretical aspects of keeping wild animals in captivity ………………………………7 1.1. The main arguments on the ethics of keeping animals in captivity……………….7 1.2. Modern viewpoints on animal welfare……………………………………………9 1.3. Modern viewpoints on animal behaviour………………………………………..13 1.3.1. Behavioural display and animal welfare……………………………….14 1.4. The role of enrichment in animal welfare………………………………………..17 1.4.1. The essence of animal training in zoos………………………………...19 1.5. The importance of human-animal relationships in the zoo………………………21 1.5.1. The importance of Umwelt consideration……………………………...23 1.5.1.1. The functional circle ………………………………………...24 1.5.2. The effect of zoo visitors on animal welfare…………………………..26 1.5.3. The effect of keeper-animal relationships on animal welfare………….28 1.6. Explaining animal communication…………………………………………........30 1.7. Socialization – a method of improving welfare of captive animals……………...36 1.7.1. The need for socialization……………………………………………...37 1.7.2. The basic mechanisms of socialization………………………………...38 2. The research methodology of a zoosemiotic approach to socialization …………………...40 2.1. Thick description of socialization………………………………………………..40 2.2. Actor-orientedness of the research……………………………………………….42 2.3. Participatory observation………………………………………………………...43 2.4. The dimensions of interpretations presented in the thesis ………………………44 3. Case-study of the socialization of Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)………………………………46 3.1. General methods of socialization………………………………………………..46 3.1.1. -

THE PHENOMENON of ABSURDITY in COMIC a Semiotic-Pragmatic Analysis of Tahilalats Comic

THE PHENOMENON OF ABSURDITY IN COMIC A Semiotic-Pragmatic Analysis of Tahilalats Comic Name: Muh. Zakky Al Masykuri Affiliation: Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia Abstract Code: ABS-ICOLLITE-20183 Introduction & Literature Review • Comics as a medium of communication to express attitudes, opinions or ideas. Comics have an extraordinary ability to adapt themselves used for various purposes (McCloud, 1993). • Tahilalats comic has the power to convey information in a popular manner, but it seems absurd to the readers. • Tahilalats comic have many signs which confused the readers, thus encouraging readers to think hard in finding the meaning conveyed. • The absurdity phenomenon portrayed in the Tahilalats comic is related to the philosophical concept of absurdity presented by Camus. • French absurde from Classical Latin absurdus, not to be heard of from ab-, intensive + surdus, dull, deaf, insensible [1]. • Absurd is the state or condition in which human beings exist in an irrational and meaningless universe and in which human life has no ultimate meaning [2]. • Absurd refers to the conflict between humans and their world (Camus, 1999). • Comics is sequential images, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer (McCloud, 1993). 1 YourDictionary. (n.d.). Absurd. In YourDictionary. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://www.yourdictionary.com/absurd 2 Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Absurd. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://www.merriam- webster.com/dictionary/absurd • Everything in human life is seen as a sign and every sign has a meaning (Hoed, 2014). • Semiotics is defined as the study of objects, events, and all cultures as signs (Wahjuwibowo, 2020). -

Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us About Human Language?

Linguistic Frontiers • 1(1) • 14-38 • 2018 DOI: 10.2478/lf-2018-0005 Linguistic Frontiers Representational Systems in Zoosemiotics and Anthroposemiotics Part I: What Have the So- Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us about Human Language? Research Article Vilém Uhlíř* Theoretical and Evolutionary Biology, Department of Philosophy and History of Sciences. Charles University. Viničná 7, 12843 Praha 2, Czech Republic Received ???, 2018; Accepted ???, 2018 Abstract: This paper offers a brief critical review of some of the so-called “Talking Animals” projects. The findings from the projects are compared with linguistic data from Homo sapiens and with newer evidence gleaned from experiments on animal syntactic skills. The question concerning what had the so-called “Talking Animals” really done is broken down into two categories – words and (recursive) syntax. The (relative) failure of the animal projects in both categories points mainly to the fact that the core feature of language – hierarchical recursive syntax – is missing in the pseudo-linguistic feats of the animals. Keywords: language • syntax • representation • meta-representation • zoosemiotics • anthroposemiotics • talking animals • general cognition • representational systems • evolutionary discontinuity • biosemiotics © Sciendo 1. The “Talking Animals” Projects For the sake of brevity, I offer a greatly selective review of some of the more important “Talking Animals” projects. Please note that many omissions were necessary for reasons of space. The “thought climate” of the 1960s and 1970s was formed largely by the Skinnerian zeitgeist, in which it seemed possible to teach any animal to master any, or almost any, skill, including language. Perhaps riding on an ideological wave, following the surprising claims of Fossey [1] and Goodall [2] concerning primates, as well as the claims of Lilly [3] and Batteau and Markey [4] concerning dolphins, many scientists and researchers focussed on the continuities between humans and other species, while largely ignoring the discontinuities and differences. -

Dialogism and Biosemiotics

Dialogism and biosemiotics AUGUSTO PONZIO The notions of ‘modeling’ and ‘interrelation’ play a pivotal role in Sebeok’s biosemiotics. In dialogue with Thomas A. Sebeok’s doctrine of signs, we propose to inquire into the action of modeling and interrelation in biosemiosis over the planet Earth, developing the concept of interrelation in terms of ‘dialogism’. Indeed, in the light of Sebeok’s biosemiotics we believe that the concept of dialogism may be extended beyond the sphere of anthroposemiosis and applied to all communication processes, which may be described as being grounded not only in the concept of modeling, but also in that of dialogism. And remembering that the concept of dialogue is fundamental in Charles S. Peirce’s thought system, we also propose that the approach we are formulating be viewed as an attempt at developing the Peircean matrix of biosemiotics. Modeling systems theory and global semiotics ‘Modeling’ and ‘interrelation’ among species-specific semioses over the entire planet Earth are two issues that Thomas A. Sebeok’s puts at the center of his ‘doctrine of signs’ — the expression he prefers to ‘science of signs’ or ‘theory of signs’. The present paper focuses on these two topics developing them in the light of our own personal perspective. The term ‘dialogism’ in the present paper designates a development with respect to the condition of interrelation in global semiosis, as described by Sebeok. In our opinion modeling and dialogism are the basis of all communication processes. Another pivotal topic in Sebeok’s ‘doctrine of signs’ is his belief that humans alone are capable of ‘semiotics’, that is, of consciousness, of what we may designate as ‘metasemiosis’, the capacity to suspend the immediacy of semiosic activity and deliberate. -

Semiowild.Pdf

SEMIOTICS IN THE WILD ESYS A S IN HONOUR OF KALEVI KULL ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 60TH BIRTHDAY Semiotics in the Wild Essays in Honour of Kalevi Kull on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday Edited by Timo Maran, Kati Lindström, Riin Magnus and Morten Tønnessen Illustrations: Aleksei Turovski Cover: Kalle Paalits Layout: Kairi Kullasepp ISBN 978–9949–32–041–7 © Department of Semiotics at the University of Tartu © Tartu University Press © authors Tartu 2012 CONTENTS 7 Kalevi Kull and the rewilding of biosemiotics. Introduction Kati Lindström, Riin Magnus, Timo Maran and Morten Tønnessen 15 Introducing a new scientific term for the study of biosemiosis Donald Favareau 25 Are we cryptos? Anton Markoš 31 Trolling and strolling through ecosemiotic realms Myrdene Anderson 39 Long live the homunculus! Some thoughts on knowing Yair Neuman 47 Introducing semetics Morten Tønnessen 55 Peirce’s ten classes of signs: Modeling biosemiotic processes and systems João Queiroz 36 The origin of mind Alexei A. Sharov 71 Is semiosis one of Darwin’s “several powers”? Terrence W. Deacon 79 Dicent symbols in mimicry João Queiroz, Frederik Stjernfelt and Charbel Niño El-Hani 87 A contribution to theoretical ecology: The biosemiotic perspective Almo Farina 95 Ecological anthropology, Actor Network Theory and the concepts of nature in a biosemiotics based on Jakob von Uexküll’s Umweltlehre Søren Brier 103 Life, lives: Mikhail Bakhtin, Ivan Kanaev, Hans Driesch, Jakob von Uexküll Susan Petrilli and Augusto Ponzio 117 Smiling snails: on semiotics and poetics of academic -

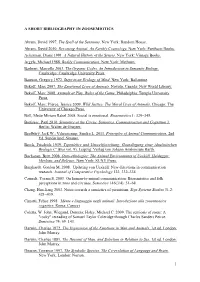

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

Messages, Signs, and Meanings: a Basic Textbook in Semiotics and Communication (Studies in Linguistic and Cultural Anthropology)

Messages, Signs, and Meanings A Basic Textbook in Semiotics and Communication 3rdedition Volume 1 in the series Studies in Linguistic and Cultural Anthropology Series Editor: Marcel Danesi, University of Toronto Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc. Toronto Disclaimer: Some images and text in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Messages, Signs, and Meanings: A Basic Textbook in Semiotics and Communication Theory, 3rdEdition by Marcel Danesi First published in 2004 by Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc. 180 Bloor Street West, Suite 801 Toronto, Ontario M5S 2V6 www.cspi.org Copyright 0 2004 Marcel Danesi and Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be photocopied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, without the written permission of Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc., except for brief passages quoted for review purposes. In the case of photocopying, a licence may be obtained from Access Copyright: One Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario, M5E 1E5, (416) 868-1620, fax (416) 868- 1621, toll-free 1-800-893-5777, www.accesscopyright.ca. Every reasonable effort has been made to identify copyright holders. CSPI would be pleased to have any errors or omissions brought to its attention. CSPl gratefully acknowledges financial support for our publishing activities from the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Danesi, Marcel, 1946- Messages and meanings : an introduction to semiotics /by Marcel Danesi - [3rd ed.] (Studies in linguistic and cultural anthropology) Previously titled: Messages and meanings : sign, thought and culture. -

Download Download

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Journals from University of Tartu 452 Kalevi Kull Sign Systems Studies 46(4), 2018, 452–466 Choosing and learning: Semiosis means choice Kalevi Kull Department of Semiotics University of Tartu, Jakobi 2, 51005 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. We examine the possibility of shift ing the concept of choice to the centre of the semiotic theory of learning. Th us, we defi ne sign process (meaning-making) through the concept of choice: semiosis is the process of making choices between simultaneously provided options. We defi ne semiotic learning as leaving traces by choices, while these traces infl uence further choices. We term such traces of choices memory. Further modifi cation of these traces (constraints) will be called habituation. Organic needs are homeostatic mechanisms coupled with choice-making. Needs and habits result in motivatedness. Semiosis as choice-making can be seen as a complementary description of the Peircean triadic model of semiosis; however, this can fi t also the models of meaning-making worked out in other shools of semiotics. We also provide a sketch for a joint typology of semiosis and learning. Keywords: biosemiotics; decision-making; free choice; general semiotics; homeostasis; need; non-algorithmicity; nowness; post-Darwinism; semiotic quanta; sign typology; types of learning Der Lebensvorgang ist nicht eine Sukzession von Ursache und Wirkung, sondern eine Entscheidung.1 Viktor von Weizsäcker (1940: 126) It would be foolish to claim that one can tackle this topic and expect to be satisfi ed. -

Semiotics of Food

Semiotica 2016; 211: 19–26 Simona Stano* Introduction: Semiotics of food DOI 10.1515/sem-2016-0095 From an anthropological point of view, food is certainly a primary need: our organism needs to be nourished in order to survive, grow, move, and develop. Nonetheless, this need is highly structured, and it involves substances, prac- tices, habits, and techniques of preparation and consumption that are part of a system of differences in signification (Barthes 1997 [1961]). Let us consider, for example, the definition of what is edible and what is not. In Cambodia, Vietnam, and many Asian countries people eat larvae, locusts, and other insects. In Peru it is usual to cook hamster and llama’s meat. In Africa and Australia it is not uncommon to eat snakes. By contrast, these same habits would probably seem odd, or at least unfamiliar, to European or North American inhabitants. Human beings eat, first of all, to survive. But in the social sphere, food assumes meanings that transcend its basic function and affect perceptions of edibility (Danesi 2004). Every culture selects, within a wide range of products with nutritional capacity, a more or less large quantity destined to become, for such a culture, “food.” And even though cultural materialism has explained these processes through functionalist and materialis- tic theories conceiving them in terms of beneficial adaptions (Harris 1985; Sahlins 1976), most scholars claim that the transformation of natural nutrients into food cannot be reduced to simple utilitarian rationality or availability logics (cf. Fischler 1980, 1990). In fact, this process is part of a classification system (Douglas 1972), so it should be rather referred to a different type of rationality, which is strictly related to symbolic representations. -

Accomplishing Identity in Participant-Denoting Discourse Stanton Wortham University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarlyCommons@Penn University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons GSE Publications Graduate School of Education January 2003 Accomplishing Identity in Participant-Denoting Discourse Stanton Wortham University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs Recommended Citation Wortham, S. (2003). Accomplishing Identity in Participant-Denoting Discourse. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/ gse_pubs/50 Published as Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, Volume 13, Issue 2, 2003, pages 189-210. © 2003 by the Regents of the University of California/ American Anthropological Association. Copying and permissions notice: Authorization to copy this content beyond fair use (as specified in Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law) for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by the Regents of the University of California/on behalf of the American Anthropological Association for libraries and other users, provided that they are registered with and pay the specified fee via Rightslink® on Caliber (http://caliber.ucpress.net/)/AnthroSource (http://www.anthrosource.net) or directly with the Copyright Clearance Center, (http://www.copyright.com ). This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/50 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Accomplishing Identity in Participant-Denoting Discourse Abstract Individuals become socially identified when categories of identity are used repeatedly to characterize them. Speech that denotes participants and involves parallelism between descriptions of participants and the events that they enact in the event of speaking can be a powerful mechanism for accomplishing consistent social identification. -

Umberto Eco on the Biosemiotics of Giorgio Prodi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Journals from University of Tartu 352 Kalevi Kull Sign Systems Studies 46(2/3), 2018, 352–364 Umberto Eco on the biosemiotics of Giorgio Prodi Kalevi Kull Department of Semiotics University of Tartu Jakobi 2, Tartu 51005, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The article provides a commentary on Umberto Eco’s text “Giorgio Prodi and the lower threshold of semiotics”. An annotated list of Prodi’s English-language publications on semiotics is included. Keywords: history of biosemiotics; lower semiotic threshold; medical semiotics Biology is pure natural semiotics. Prodi 1986b: 122 Is it by law or by nature that the image of Mickey Mouse reminds us of a mouse? Eco 1999: 339 “When I discovered the research of Giorgio Prodi on biosemiotics I was the person to publish his book that maybe I was not in total agreement with, but I found it was absolutely important to speak about those things”, Umberto Eco said during our conversation in Milan in 2012. Indeed, two books by Prodi – Orizzonti della genetica (Prodi 1979; series Espresso Strumenti) and La storia naturale della logica (Prodi 1982; series Studi Bompiani: Il campo semiotico) – appeared in series edited by Eco. Giorgio Prodi was a biologist whom Eco highly valued, an expert and an encyclopedia for him in the fields of biology and medicine, a scholar whose work in biosemiotics Eco took very seriously. Eco spoke about this in a talk from 1988 (Eco 2018), saying that he had been suspicious of semiotic approaches to cells until he met Prodi in 1974.