Thomas A. Sebeok and Biology: Building Biosemiotics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja the ZOOSEMIOTICS of SOCIALIZATION

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja THE ZOOSEMIOTICS OF SOCIALIZATION: CASE-STUDY IN SOCIALIZING RED FOX (VULPES VULPES) IN TANGEN ANIMAL PARK, NORWAY Master’s Thesis Supervisors: Timo Maran, Ph.D Nelly Mäekivi, M.A Tartu 2014 CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….4 1. The theoretical aspects of keeping wild animals in captivity ………………………………7 1.1. The main arguments on the ethics of keeping animals in captivity……………….7 1.2. Modern viewpoints on animal welfare……………………………………………9 1.3. Modern viewpoints on animal behaviour………………………………………..13 1.3.1. Behavioural display and animal welfare……………………………….14 1.4. The role of enrichment in animal welfare………………………………………..17 1.4.1. The essence of animal training in zoos………………………………...19 1.5. The importance of human-animal relationships in the zoo………………………21 1.5.1. The importance of Umwelt consideration……………………………...23 1.5.1.1. The functional circle ………………………………………...24 1.5.2. The effect of zoo visitors on animal welfare…………………………..26 1.5.3. The effect of keeper-animal relationships on animal welfare………….28 1.6. Explaining animal communication…………………………………………........30 1.7. Socialization – a method of improving welfare of captive animals……………...36 1.7.1. The need for socialization……………………………………………...37 1.7.2. The basic mechanisms of socialization………………………………...38 2. The research methodology of a zoosemiotic approach to socialization …………………...40 2.1. Thick description of socialization………………………………………………..40 2.2. Actor-orientedness of the research……………………………………………….42 2.3. Participatory observation………………………………………………………...43 2.4. The dimensions of interpretations presented in the thesis ………………………44 3. Case-study of the socialization of Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)………………………………46 3.1. General methods of socialization………………………………………………..46 3.1.1. -

Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us About Human Language?

Linguistic Frontiers • 1(1) • 14-38 • 2018 DOI: 10.2478/lf-2018-0005 Linguistic Frontiers Representational Systems in Zoosemiotics and Anthroposemiotics Part I: What Have the So- Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us about Human Language? Research Article Vilém Uhlíř* Theoretical and Evolutionary Biology, Department of Philosophy and History of Sciences. Charles University. Viničná 7, 12843 Praha 2, Czech Republic Received ???, 2018; Accepted ???, 2018 Abstract: This paper offers a brief critical review of some of the so-called “Talking Animals” projects. The findings from the projects are compared with linguistic data from Homo sapiens and with newer evidence gleaned from experiments on animal syntactic skills. The question concerning what had the so-called “Talking Animals” really done is broken down into two categories – words and (recursive) syntax. The (relative) failure of the animal projects in both categories points mainly to the fact that the core feature of language – hierarchical recursive syntax – is missing in the pseudo-linguistic feats of the animals. Keywords: language • syntax • representation • meta-representation • zoosemiotics • anthroposemiotics • talking animals • general cognition • representational systems • evolutionary discontinuity • biosemiotics © Sciendo 1. The “Talking Animals” Projects For the sake of brevity, I offer a greatly selective review of some of the more important “Talking Animals” projects. Please note that many omissions were necessary for reasons of space. The “thought climate” of the 1960s and 1970s was formed largely by the Skinnerian zeitgeist, in which it seemed possible to teach any animal to master any, or almost any, skill, including language. Perhaps riding on an ideological wave, following the surprising claims of Fossey [1] and Goodall [2] concerning primates, as well as the claims of Lilly [3] and Batteau and Markey [4] concerning dolphins, many scientists and researchers focussed on the continuities between humans and other species, while largely ignoring the discontinuities and differences. -

BIOSEMIOSIS and CAUSATION: DEFENDING BIOSEMIOTICS THROUGH ROSEN’S THEORETICAL BIOLOGY OR INTEGRATING BIOSEMIOTICS and ANTICIPATORY SYSTEMS THEORY1 Arran Gare

Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, vol. 15, no. 1, 2019 BIOSEMIOSIS AND CAUSATION: DEFENDING BIOSEMIOTICS THROUGH ROSEN’S THEORETICAL BIOLOGY OR INTEGRATING BIOSEMIOTICS AND 1 ANTICIPATORY SYSTEMS THEORY Arran Gare ABSTRACT: The fracture in the emerging discipline of biosemiotics when the code biologist Marcello Barbieri claimed that Peircian biosemiotics is not genuine science raises anew the question: What is science? When it comes to radically new approaches in science, there is no simple answer to this question, because if successful, these new approaches change what is understood to be science. This is what Galileo, Darwin and Einstein did to science, and with quantum theory, opposing interpretations are not merely about what theory is right, but what is real science. Peirce’s work, as he acknowledged, is really a continuation of efforts of Schelling to challenge the heritage of Newtonian science for the very good reason that the deep assumptions of Newtonian science had made sentient life, human consciousness and free will unintelligible, the condition for there being science. Pointing out the need for such a revolution in science has not succeeded as a defence of Peircian biosemiotics, however. In this paper, I will defend the scientific credentials of Peircian biosemiotics by relating it to the theoretical biology of the bio-mathematician, Robert Rosen. Rosen’s relational biology, focusing on anticipatory systems and giving a place to final causes, should also be seen as a rigorous development of the Schellingian project to conceive nature in such a way that the emergence of sentient life, mind and science are intelligible. -

Biosemiotic Medicine: from an Effect-Based Medicine to a Process-Based Medicine

Special article Arch Argent Pediatr 2020;118(5):e449-e453 / e449 Biosemiotic medicine: From an effect-based medicine to a process-based medicine Carlos G. Musso, M.D., Ph.D.a,b ABSTRACT Such knowledge evidences the Contemporary medicine is characterized by an existence of a large and intricate increasing subspecialization and the acquisition of a greater knowledge about the interaction among interconnected network among the the different body structures (biosemiotics), different body structures, which both in health and disease. This article proposes accounts for a sort of “communication a new conceptualization of the body based on channel” among its elements, a true considering it as a biological space (cells, tissues, and organs) and a biosemiotic space (exchange of “dialogic or semiotic space” that is signs among them). Its development would lead conceptually abstract but experientially to a new subspecialty focused on the study and real, through which normal and interference of disease biosemiotics (biosemiotic pathological intra- and inter- medicine), which would trigger a process- based medicine centered on early diagnosis and parenchymal dialogs (sign exchange) management of disease. occur. Such dialogs determine a Key words: medicine, biosemiotics, diagnosis, balanced functioning of organ systems therapy. or the onset and establishment of http://dx.doi.org/10.5546/aap.2020.eng.e449 disease, respectively. The investigation and analysis of such phenomenon is the subject of a relative new discipline: To cite: Musso CG. Biosemiotic medicine: From an biosemiotics, which deals with the effect-based medicine to a process-based medicine. 1 Arch Argent Pediatr 2020;118(5):e449-e453. study of the natural world’s language. -

Dialogism and Biosemiotics

Dialogism and biosemiotics AUGUSTO PONZIO The notions of ‘modeling’ and ‘interrelation’ play a pivotal role in Sebeok’s biosemiotics. In dialogue with Thomas A. Sebeok’s doctrine of signs, we propose to inquire into the action of modeling and interrelation in biosemiosis over the planet Earth, developing the concept of interrelation in terms of ‘dialogism’. Indeed, in the light of Sebeok’s biosemiotics we believe that the concept of dialogism may be extended beyond the sphere of anthroposemiosis and applied to all communication processes, which may be described as being grounded not only in the concept of modeling, but also in that of dialogism. And remembering that the concept of dialogue is fundamental in Charles S. Peirce’s thought system, we also propose that the approach we are formulating be viewed as an attempt at developing the Peircean matrix of biosemiotics. Modeling systems theory and global semiotics ‘Modeling’ and ‘interrelation’ among species-specific semioses over the entire planet Earth are two issues that Thomas A. Sebeok’s puts at the center of his ‘doctrine of signs’ — the expression he prefers to ‘science of signs’ or ‘theory of signs’. The present paper focuses on these two topics developing them in the light of our own personal perspective. The term ‘dialogism’ in the present paper designates a development with respect to the condition of interrelation in global semiosis, as described by Sebeok. In our opinion modeling and dialogism are the basis of all communication processes. Another pivotal topic in Sebeok’s ‘doctrine of signs’ is his belief that humans alone are capable of ‘semiotics’, that is, of consciousness, of what we may designate as ‘metasemiosis’, the capacity to suspend the immediacy of semiosic activity and deliberate. -

Roman Jakobson, Parallelism, and Structural Poetics

Chapter 2 Roman Jakobson, Parallelism, and Structural Poetics In the early to mid-twentieth century these very issues regarding the conver- gence of poetics, style, language, and discourse structure were being exten- sively explored by eastern European literary theorists.1 The discipline that eventually emerged from the movement became variously known as, “critical theory, semiotics, structuralism, literary linguistics, cultural studies,”2 and one could add “structural poetics.” The movement was also in many ways a pre- cursor to DA. Structural poetics pioneered the analysis of literature, namely poetry, as discursive linguistic communicative function, or to use their termi- nology, a “semiotic system.” Saussurean structural linguistics functioned as the theoretical bedrock for evaluating literary texts as discourse. It is to Saussure’s theory of language that we now turn. 2.1 Structuralism, Structural Semiotics, Linguistics, and Discursivity French linguist Ferdinand de Saussure innovatively conceptualised language (Fr. langue) as an integrated and organised system of signs (i.e., semiotic sys- tem) whose various parts, or constituents (i.e., signs or signifiers), are only properly understood as a part of the greater structural (i.e., semiotic) system. Saussure conceived of gross constituent units, or “constituents” for short, as ar- bitrary signifiers (signs) that point to something meaningful (signified). There is a distinction, then, between the signified (meaning) and the signifier (form). The sign, or signifier, is the form that that which is meaningful (i.e., signified) takes within the system of forms. Implicit to this concept of the signifier and the signified is the idea that signification is activated precisely through the sign’s place within the greater 1 This movement is most directly associated with various schools of literary linguistic theory including New Criticism, Russian Formalism (or simply “formalism”), the Prague School, Structuralism, and Czech Structuralism. -

Semiowild.Pdf

SEMIOTICS IN THE WILD ESYS A S IN HONOUR OF KALEVI KULL ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 60TH BIRTHDAY Semiotics in the Wild Essays in Honour of Kalevi Kull on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday Edited by Timo Maran, Kati Lindström, Riin Magnus and Morten Tønnessen Illustrations: Aleksei Turovski Cover: Kalle Paalits Layout: Kairi Kullasepp ISBN 978–9949–32–041–7 © Department of Semiotics at the University of Tartu © Tartu University Press © authors Tartu 2012 CONTENTS 7 Kalevi Kull and the rewilding of biosemiotics. Introduction Kati Lindström, Riin Magnus, Timo Maran and Morten Tønnessen 15 Introducing a new scientific term for the study of biosemiosis Donald Favareau 25 Are we cryptos? Anton Markoš 31 Trolling and strolling through ecosemiotic realms Myrdene Anderson 39 Long live the homunculus! Some thoughts on knowing Yair Neuman 47 Introducing semetics Morten Tønnessen 55 Peirce’s ten classes of signs: Modeling biosemiotic processes and systems João Queiroz 36 The origin of mind Alexei A. Sharov 71 Is semiosis one of Darwin’s “several powers”? Terrence W. Deacon 79 Dicent symbols in mimicry João Queiroz, Frederik Stjernfelt and Charbel Niño El-Hani 87 A contribution to theoretical ecology: The biosemiotic perspective Almo Farina 95 Ecological anthropology, Actor Network Theory and the concepts of nature in a biosemiotics based on Jakob von Uexküll’s Umweltlehre Søren Brier 103 Life, lives: Mikhail Bakhtin, Ivan Kanaev, Hans Driesch, Jakob von Uexküll Susan Petrilli and Augusto Ponzio 117 Smiling snails: on semiotics and poetics of academic -

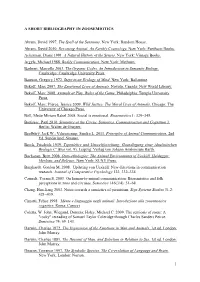

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

A Biosemiotic Framework for Artificial Autonomous Sign Users

A Biosemiotic Framework for Artificial Autonomous Sign Users Erich Prem Austrian Research Institute for Artificial Intelligence Freyung 6/2/2 A-1010 Vienna, Austria [email protected] Abstract It is all the more surprising that recent publications in this In this paper we critically analyse fundamental assumptions area rarely address foundational is-sues concerning the underlying approaches to symbol anchoring and symbol semantics of system-environment interactions or other grounding. A conceptual framework inspired by problems related to biosemiotics (a notable exception is biosemiotics is developed for the study of signs in (Cangelosi 01)). As we will discuss below, the approaches autonomous artificial sign users. Our theory of reference make little or no reference to specifically life-like or even uses an ethological analysis of animal-environment robotic characteristics such as goal-directedness, interaction. We first discuss semiotics with respect to the purposiveness, or the dynamics of system-environment meaning of signals taken up from the environment of an interaction. These features are, however, central to much autonomous agent. We then show how semantic issues arise of robotics and ALife. It is highly questionable, however, in a similar way in the study of adaptive artificial sign us- ers. Anticipation and adaptation play the important role of whether technical approaches to symbol anchoring should defining purpose which is a neces-sary concept in the be developed devoid of any sound theoretical foundation semiotics of learning robots. The proposed focus on sign for concepts such as “meaning” or “reference”. Until now, acts leads to a se-mantics in which meaning and reference simplistic versions of Fregean or Peircean semiotics seem are based on the anticipated outcome of sign-based in- to have motivated existing technical symbol anchoring and teraction. -

[email protected]

Palacký University, Olomouc Roman O. Jakobson: A Work in Progress edited and with an introduction by Tomáš Kubíček and Andrew Lass Olomouc 2014 Recenzenti: prof. PhDr. Petr A. Bílek, CSc. prof. PhDr. Dagmar Mocná, CSc. Publikace vznikla v rámci projektu Inovace bohemistických studií v mezioborových kontextech. Tento projekt je spolufi nancován Evropským sociálním fondem a státním rozpočtem České republiky. Zpracování a vydání publikace bylo umožněno díky fi nanční podpoře udělené roku 2014 Ministerstvem školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy ČR v rámci Institucionálního rozvojového plánu, programu V. Excelence, Filozofi cké fakultě Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci: Zlepšení publikačních možností akademických pedagogů ve fi lologických a humanitních oborech. Neoprávněné užití tohoto díla je porušením autorských práv a může zakládat občanskoprávní, správněprávní, popř. trestněprávní odpovědnost. Editors © Tomáš Kubíček and Andrew Lass, 2014 © Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, 2014 ISBN 978-80-244-4386-7 Neprodejná publikace Content Introduction .................................................................................................................5 Parallelism in prose ...................................................................................................11 Wolf Schmid Reopening the “Closing statement”: Jakobson’s factors and functions in our Google Galaxy .......................................25 Peter W. Nesselroth Elective Affi nities: Roman Jakobson, Claude Lévi-Strauss and his Antropologie Structurale ..............................................................................37 -

Download Download

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Journals from University of Tartu 452 Kalevi Kull Sign Systems Studies 46(4), 2018, 452–466 Choosing and learning: Semiosis means choice Kalevi Kull Department of Semiotics University of Tartu, Jakobi 2, 51005 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. We examine the possibility of shift ing the concept of choice to the centre of the semiotic theory of learning. Th us, we defi ne sign process (meaning-making) through the concept of choice: semiosis is the process of making choices between simultaneously provided options. We defi ne semiotic learning as leaving traces by choices, while these traces infl uence further choices. We term such traces of choices memory. Further modifi cation of these traces (constraints) will be called habituation. Organic needs are homeostatic mechanisms coupled with choice-making. Needs and habits result in motivatedness. Semiosis as choice-making can be seen as a complementary description of the Peircean triadic model of semiosis; however, this can fi t also the models of meaning-making worked out in other shools of semiotics. We also provide a sketch for a joint typology of semiosis and learning. Keywords: biosemiotics; decision-making; free choice; general semiotics; homeostasis; need; non-algorithmicity; nowness; post-Darwinism; semiotic quanta; sign typology; types of learning Der Lebensvorgang ist nicht eine Sukzession von Ursache und Wirkung, sondern eine Entscheidung.1 Viktor von Weizsäcker (1940: 126) It would be foolish to claim that one can tackle this topic and expect to be satisfi ed. -

Review: Marcello Barbieri (Ed) (2007) Introduction to Biosemiotics. the New Biological Synthesis

tripleC 5(3): 104-109, 2007 ISSN 1726-670X http://tripleC.uti.at Review: Marcello Barbieri (Ed) (2007) Introduction to Biosemiotics. The new biological synthesis. Dordrecht: Springer Günther Witzany telos – Philosophische Praxis Vogelsangstr. 18c A-5111-Buermoos/Salzburg Austria E-mail: [email protected] 1 Thematic background without utterances we act as non-uttering indi- viduals being dependent on the discourse de- Maybe it is no chance that the discovery of the rived meaning processes of a linguistic (e.g. sci- genetic code occurred during the hot phase of entific) community. philosophy of science discourse about the role of This position marks the primary difference to language in generating models of scientific ex- the subject of knowledge of Kantian knowledge planation. The code-metaphor was introduced theories wherein one subject alone in principle parallel to other linguistic terms to denote lan- could be able to generate sentences in which it guage like features of the nucleic acid sequence generates knowledge. This abstractive fallacy molecules such as “code without commas” was ruled out in the early 50s of the last century (Francis Crick). At the same time the 30 years of being replaced by the “community of investiga- trying to establish an exact scientific language to tors” (Peirce) represented by the scientific com- delimit objective sentences from non-objective munity in which every single scientist is able the ones derived one of his peaks in the linguistic place his utterance looking for being integrated turn. in the discourse community in which his utter- ances will be proven whether they are good ar- 1.1 Changing subjects of knowledge guments or not.