The Role of Ethology in Animal Welfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja the ZOOSEMIOTICS of SOCIALIZATION

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja THE ZOOSEMIOTICS OF SOCIALIZATION: CASE-STUDY IN SOCIALIZING RED FOX (VULPES VULPES) IN TANGEN ANIMAL PARK, NORWAY Master’s Thesis Supervisors: Timo Maran, Ph.D Nelly Mäekivi, M.A Tartu 2014 CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….4 1. The theoretical aspects of keeping wild animals in captivity ………………………………7 1.1. The main arguments on the ethics of keeping animals in captivity……………….7 1.2. Modern viewpoints on animal welfare……………………………………………9 1.3. Modern viewpoints on animal behaviour………………………………………..13 1.3.1. Behavioural display and animal welfare……………………………….14 1.4. The role of enrichment in animal welfare………………………………………..17 1.4.1. The essence of animal training in zoos………………………………...19 1.5. The importance of human-animal relationships in the zoo………………………21 1.5.1. The importance of Umwelt consideration……………………………...23 1.5.1.1. The functional circle ………………………………………...24 1.5.2. The effect of zoo visitors on animal welfare…………………………..26 1.5.3. The effect of keeper-animal relationships on animal welfare………….28 1.6. Explaining animal communication…………………………………………........30 1.7. Socialization – a method of improving welfare of captive animals……………...36 1.7.1. The need for socialization……………………………………………...37 1.7.2. The basic mechanisms of socialization………………………………...38 2. The research methodology of a zoosemiotic approach to socialization …………………...40 2.1. Thick description of socialization………………………………………………..40 2.2. Actor-orientedness of the research……………………………………………….42 2.3. Participatory observation………………………………………………………...43 2.4. The dimensions of interpretations presented in the thesis ………………………44 3. Case-study of the socialization of Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)………………………………46 3.1. General methods of socialization………………………………………………..46 3.1.1. -

Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us About Human Language?

Linguistic Frontiers • 1(1) • 14-38 • 2018 DOI: 10.2478/lf-2018-0005 Linguistic Frontiers Representational Systems in Zoosemiotics and Anthroposemiotics Part I: What Have the So- Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us about Human Language? Research Article Vilém Uhlíř* Theoretical and Evolutionary Biology, Department of Philosophy and History of Sciences. Charles University. Viničná 7, 12843 Praha 2, Czech Republic Received ???, 2018; Accepted ???, 2018 Abstract: This paper offers a brief critical review of some of the so-called “Talking Animals” projects. The findings from the projects are compared with linguistic data from Homo sapiens and with newer evidence gleaned from experiments on animal syntactic skills. The question concerning what had the so-called “Talking Animals” really done is broken down into two categories – words and (recursive) syntax. The (relative) failure of the animal projects in both categories points mainly to the fact that the core feature of language – hierarchical recursive syntax – is missing in the pseudo-linguistic feats of the animals. Keywords: language • syntax • representation • meta-representation • zoosemiotics • anthroposemiotics • talking animals • general cognition • representational systems • evolutionary discontinuity • biosemiotics © Sciendo 1. The “Talking Animals” Projects For the sake of brevity, I offer a greatly selective review of some of the more important “Talking Animals” projects. Please note that many omissions were necessary for reasons of space. The “thought climate” of the 1960s and 1970s was formed largely by the Skinnerian zeitgeist, in which it seemed possible to teach any animal to master any, or almost any, skill, including language. Perhaps riding on an ideological wave, following the surprising claims of Fossey [1] and Goodall [2] concerning primates, as well as the claims of Lilly [3] and Batteau and Markey [4] concerning dolphins, many scientists and researchers focussed on the continuities between humans and other species, while largely ignoring the discontinuities and differences. -

Animal Welfare and the Paradox of Animal Consciousness

ARTICLE IN PRESS Animal Welfare and the Paradox of Animal Consciousness Marian Dawkins1 Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK 1Corresponding author: e-mail address: [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Animal Consciousness: The Heart of the Paradox 2 2.1 Behaviorism Applies to Other People Too 5 3. Human Emotions and Animals Emotions 7 3.1 Physiological Indicators of Emotion 7 3.2 Behavioral Components of Emotion 8 3.2.1 Vacuum Behavior 10 3.2.2 Rebound 10 3.2.3 “Abnormal” Behavior 10 3.2.4 The Animal’s Point of View 11 3.2.5 Cognitive Bias 15 3.2.6 Expressions of the Emotions 15 3.3 The Third Component of Emotion: Consciousness 16 4. Definitions of Animal Welfare 24 5. Conclusions 26 References 27 1. INTRODUCTION Consciousness has always been both central to and a stumbling block for animal welfare. On the one hand, the belief that nonhuman animals suffer and feel pain is what draws many people to want to study animal welfare in the first place. Animal welfare is seen as fundamentally different from plant “welfare” or the welfare of works of art precisely because of the widely held belief that animals have feelings and experience emotions in ways that plants or inanimate objectsdhowever valuableddo not (Midgley, 1983; Regan, 1984; Rollin, 1989; Singer, 1975). On the other hand, consciousness is also the most elusive and difficult to study of any biological phenomenon (Blackmore, 2012; Koch, 2004). Even with our own human consciousness, we are still baffled as to how Advances in the Study of Behavior, Volume 47 ISSN 0065-3454 © 2014 Elsevier Inc. -

How Welfare Biology and Commonsense May Help to Reduce Animal Suffering

Ng, Yew-Kwang (2016) How welfare biology and commonsense may help to reduce animal suffering. Animal Sentience 7(1) DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1012 This article has appeared in the journal Animal Sentience, a peer-reviewed journal on animal cognition and feeling. It has been made open access, free for all, by WellBeing International and deposited in the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ng, Yew-Kwang (2016) How welfare biology and commonsense may help to reduce animal suffering. Animal Sentience 7(1) DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1012 Cover Page Footnote I am grateful to Dr. Timothy D. Hau of the University of Hong Kong for assistance. This article is available in Animal Sentience: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/ animsent/vol1/iss7/1 Animal Sentience 2016.007: Ng on Animal Suffering Call for Commentary: Animal Sentience publishes Open Peer Commentary on all accepted target articles. Target articles are peer-reviewed. Commentaries are editorially reviewed. There are submitted commentaries as well as invited commentaries. Commentaries appear as soon as they have been revised and accepted. Target article authors may respond to their commentaries individually or in a joint response to multiple commentaries. Instructions: http://animalstudiesrepository.org/animsent/guidelines.html How welfare biology and commonsense may help to reduce animal suffering Yew-Kwang Ng Division of Economics Nanyang Technological University Singapore Abstract: Welfare biology is the study of the welfare of living things. Welfare is net happiness (enjoyment minus suffering). Since this necessarily involves feelings, Dawkins (2014) has suggested that animal welfare science may face a paradox, because feelings are very difficult to study. -

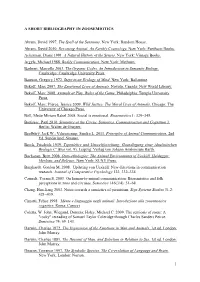

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

Mental States in Animals: Cognitive Ethology Jacques Vauclair

Mental states in animals: cognitive ethology Jacques Vauclair This artHe addresses the quegtion of mentaJ states in animak as viewed in ‘cognitive ethology”. In effect, thk field of research aims at studying naturally occurring behaviours such as food caching, individual recognition, imitation, tool use and communication in wild animals, in order to seek for evidence of mental experiences, self-aw&&reness and intentional@. Cognitive ethologists use some philosophical cencepts (e.g., the ‘intentional stance’) to carry out their programme of the investigation of natural behaviours. A comparison between cognitive ethology and other approaches to the investigation of cognitive processes in animals (e.g., experimental animal psychology) helps to point out the strengths and weaknesses of cognitive ethology. Moreover, laboratory attempts to analyse experimentally Mentional behaviours such as deception, the relationship between seeing and knowing, as well as the ability of animals to monitor their own states of knowing, suggest that cognitive ethology could benefit significantly from the conceptual frameworks and methods of animal cognitive psychology. Both disciplines could, in fact, co&ribute to the understanding of which cognitive abilities are evolutionary adaptations. T he term ‘cognirive ethology’ (CE) was comed by that it advances a purposive or Intentional interpretation Griffin in The Question ofAnimd Au~aarmess’ and later de- for activities which are a mixture of some fixed genetically veloped in other publications’ ‘_ Although Griffin‘s IS’6 transmitred elements with more hexible behaviour?. book was first a strong (and certainly salutary) reacrion (Cognitive ethologists USC conceptual frameworks against the inhibitions imposed by strict behaviourism in provided by philosophers (such as rhe ‘intentional stance’)“. -

Human Origins

HUMAN ORIGINS Methodology and History in Anthropology Series Editors: David Parkin, Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford David Gellner, Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford Volume 1 Volume 17 Marcel Mauss: A Centenary Tribute Learning Religion: Anthropological Approaches Edited by Wendy James and N.J. Allen Edited by David Berliner and Ramon Sarró Volume 2 Volume 18 Franz Baerman Steiner: Selected Writings Ways of Knowing: New Approaches in the Anthropology of Volume I: Taboo, Truth and Religion. Knowledge and Learning Franz B. Steiner Edited by Mark Harris Edited by Jeremy Adler and Richard Fardon Volume 19 Volume 3 Difficult Folk? A Political History of Social Anthropology Franz Baerman Steiner. Selected Writings By David Mills Volume II: Orientpolitik, Value, and Civilisation. Volume 20 Franz B. Steiner Human Nature as Capacity: Transcending Discourse and Edited by Jeremy Adler and Richard Fardon Classification Volume 4 Edited by Nigel Rapport The Problem of Context Volume 21 Edited by Roy Dilley The Life of Property: House, Family and Inheritance in Volume 5 Béarn, South-West France Religion in English Everyday Life By Timothy Jenkins By Timothy Jenkins Volume 22 Volume 6 Out of the Study and Into the Field: Ethnographic Theory Hunting the Gatherers: Ethnographic Collectors, Agents and Practice in French Anthropology and Agency in Melanesia, 1870s–1930s Edited by Robert Parkin and Anna de Sales Edited by Michael O’Hanlon and Robert L. Welsh Volume 23 Volume 7 The Scope of Anthropology: Maurice Godelier’s Work in Anthropologists in a Wider World: Essays on Field Context Research Edited by Laurent Dousset and Serge Tcherkézoff Edited by Paul Dresch, Wendy James, and David Parkin Volume 24 Volume 8 Anyone: The Cosmopolitan Subject of Anthropology Categories and Classifications: Maussian Reflections on By Nigel Rapport the Social Volume 25 By N.J. -

Scientific Advances in the Study of Animal Welfare

Scientific advances in the study of animal welfare How we can more effectively Why Pain? assess pain… Matt Leach To recognise it, you need to define it… ‘Pain is an unpleasant sensory & emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage’ IASP 1979 As it is the emotional component that is critical for our welfare, the same will be true for animals Therefore we need indices that reflect this component! Q. How do we assess experience? • As it is subjective, direct assessment is difficult.. • Unlike in humans we do not have a gold standard – i.e. Self-report – Animals cannot meaningfully communicate with us… • So we traditionally use proxy indices Derived from inferential reasoning Infer presence of pain in animals from behavioural, anatomical, physiological & biochemical similarity to humans In humans, if pain induces a change & that change is prevented by pain relief, then it is used to assess pain If the same occurs in animals, then we assume that they can be used to assess pain Quantitative sensory testing • Application of standardised noxious stimuli to induce a reflex response – Mechanical, thermal or electrical… – Used to measure nociceptive (i.e. sensory) thresholds • Wide range of methods used – Choice depends on type of pain (acute / chronic) modeled • Elicits specific behavioural response (e.g. withdrawal) – Latency & frequency of response routinely measured – Intensity of stimulus required to elicit a response • Easy to use, but difficult to master… Value? • What do these tests tell us: – Fundamental nociceptive mechanisms & central processing – It measures evoked pain, not spontaneous pain • Tests of hypersensitivity not pain per se (Different mechanisms) • What don’t these tests tell us: – Much about the emotional component of pain • Measures nociceptive (sensory) thresholds based on autonomic responses (e.g. -

Human Social Behavioral Systems:Ethological

Human Ethology Bulletin 29 (2014)1: 39-65 Teoretical Reviews HUMAN SOCIAL BEHAVIORL SYSTEMS: ETHOLOGICAL FRMEWORK FOR A UNIFIED THEORY Liane J. Leedom University of Bridgeport, Psychology Department, CT, US [email protected] ABSTRCT Drive theories of motivation proposed by Lorenz and Tinbergen did not survive experimental scrutiny; however these were replaced by the behavioral systems famework. Unfortunately, political forces within science including the rise of sociobiology and comparative psychology, caused neglect of this important famework. Tis review revives the concept of behavioral systems and demonstrates its utility in the development of a unifed theory of human social behavior and social bonding. Although the term “atachment” has been used to indicate social bonds which motivate afliation, four diferentiable social reward systems mediate social proximity and bond formation: the afliation (atachment), caregiving, dominance and sexual behavioral systems. Ethology is dedicated to integrating inborn capacities with experiential learning as well as the proximal and ultimate causes of behavior. Hence, the behavioral systems famework developed by ethologists nearly 50 years ago, enables discussion of a unifed theory of human social behavior. Key words: atachment, caregiving, dominance, sex, behavioral systems _________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Te last 50 years has seen the waning of ethology in the United States, accompanied by the growth of sociobiology, comparative psychology and evolutionary psychology (Barlow, 1989; Burkhardt, 2005; Greenberg, 2010). Sociobiologists, in particular, proclaimed the death of ethology and promised their nascent discipline and genetic mechanisms would provide an understanding of human social behavior (Barlow, 1989; E. O. Wilson, 2000). It has been 13 years since the sequencing of the human genome (Venter et al., 2001), sociobiology has fallen into “disarray” (D. -

Cognitive Ethology: Theory Or Poetry?

Cognitive ethology: Theory or poetry? Jonathan Bennett from Behavioral and Brain Sciences 6 (1983), pp. 356–358. Comments on Daniel Dennett, ‘Intentional Systems in Cognitive Ethology: the “Panglossian Paradigm” defended’. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 6 (1983), pp. 343–345. Dennett is perhaps the most interesting, fertile, and chal- I take it as uncontroversial that the intentional stance— lenging philosopher of mind on the contemporary scene, and considered as a program for theorizing about behavior—must I count myself among his grateful admirers. But this present be centered on the idea that beliefs are functions from desires paper of his, enjoyable as it is to read, and acceptable as to behavior, and that desires are functions from beliefs to its conclusions are, is likely to do more harm than good. behavior. Down in the foundations, then, we need some Some will object that the intentional stance is a dead end; theory about what behavior must be like to be reasonably but I think, as Dennett does, that it is premature to turn interpreted as manifesting beliefs and desires; and these our backs on explanations of animal behavior in terms of concepts must presumably tail off somehow, being strongly desires and beliefs, and I am in favor of continuing with applicable to men and apes, less strongly to monkeys, and this endeavor; but only if it gets some structure, only if it so on down to animals that do not have beliefs and desires is guided by some firm underlying theory. That is what but can be described in terms of weaker analogues of those the ethologists might get from philosophy, but Dennett has notions. -

Human Ethology Bulletin

Human Ethology Bulletin VOLUME 19, ISSUE 4 ISSN 0739‐2036 December 2004 © 2004 The International Society for Human Ethology ISHE website: http://evolution.anthro.univie.ac.at/ishe.html The 17th Biennial ISHE Conference was held in Ghent, Belgium from July 27‐30. Report on ISHE 2004 The program was published in the June 2004 issue, and the Minutes of the General by Kris Thienpont Assembly appeared in the previous issue. This issue includes additional photographs Ghent is a city with many faces. One of the from the meeting, as well as a report on the better known sides is its annual week of meeting authored by conference host (and exuberant festivities at the end of July, with recently appointed Associate Book Review hundreds of concerts, performances, street Editor), Kris Theinpont. Also in this issue is art exhibits, thousands of people in and a revised version of the tribute to Linda around the city center, and the odd Mealey that Andy Thomson delivered in scientific society that considers that Ghent. particular week as a good occasion for organizing a conference. Additional information on the conference, including photographs and abstracts of ISHE participants arriving in Ghent on papers, can be found at: th Monday 26 were met with the state of www.psw.ugent.be/bevolk/ishe2004 pleasant chaos that accompanies the Ghent Festivities and could enjoy the last day and night of this annual bacchanaal. Fortunately, our meeting began the day after, when the dust had settled, the streets had been cleaned, and the public transport system had gone on strike. -

Syllabus a History of Animals in the Atlantic World

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, El Primer Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno, ed. Rolena Adorno (Copenhagen: Royal Library Digital Facsimile, 2002), 1105. Special topics: A history of animals in the atlantic world History 497, section 001 Abel Alves Spring Semester 2011 Burkhardt Building 216 Monday, 6:30-9:10 PM [email protected]; 285-8729 Burkhardt Building 106 Office Hours: Monday, 5:00-6:30; also by appointment Prospectus The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss once wrote that animals are not only “good to eat,” they are “good to think.” Throughout the course of human history, people have interacted with other animals, not only using them for food, clothing, labor and entertainment, but also associating with them as pets and companions, and even appreciating their behaviors intrinsically. Nonhuman animals have been our symbols and models, and they have even channeled the sacred for us. This course will explore the interaction of humans with other animals in the context of the Atlantic World from prehistoric times to the present. Our case studies will include an exploration of our early hominid heritage as prey as well as predators; our domestication of other animals to fit our cultural needs; how nonhuman animals were used and sometimes respected in early agrarian empires like those of Rome and the Aztecs; how Native American, African and Christian religious traditions have wrestled with the concept of the “animal”; the impact of the Enlightenment and Darwinian thought; and the contemporary mechanization of life and call for animal rights. Throughout the semester, we will be giving other animals “voice,” even as Aristotle in The Politics said they possessed the ability to communicate.