University of Tartu Sign Systems Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja the ZOOSEMIOTICS of SOCIALIZATION

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja THE ZOOSEMIOTICS OF SOCIALIZATION: CASE-STUDY IN SOCIALIZING RED FOX (VULPES VULPES) IN TANGEN ANIMAL PARK, NORWAY Master’s Thesis Supervisors: Timo Maran, Ph.D Nelly Mäekivi, M.A Tartu 2014 CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….4 1. The theoretical aspects of keeping wild animals in captivity ………………………………7 1.1. The main arguments on the ethics of keeping animals in captivity……………….7 1.2. Modern viewpoints on animal welfare……………………………………………9 1.3. Modern viewpoints on animal behaviour………………………………………..13 1.3.1. Behavioural display and animal welfare……………………………….14 1.4. The role of enrichment in animal welfare………………………………………..17 1.4.1. The essence of animal training in zoos………………………………...19 1.5. The importance of human-animal relationships in the zoo………………………21 1.5.1. The importance of Umwelt consideration……………………………...23 1.5.1.1. The functional circle ………………………………………...24 1.5.2. The effect of zoo visitors on animal welfare…………………………..26 1.5.3. The effect of keeper-animal relationships on animal welfare………….28 1.6. Explaining animal communication…………………………………………........30 1.7. Socialization – a method of improving welfare of captive animals……………...36 1.7.1. The need for socialization……………………………………………...37 1.7.2. The basic mechanisms of socialization………………………………...38 2. The research methodology of a zoosemiotic approach to socialization …………………...40 2.1. Thick description of socialization………………………………………………..40 2.2. Actor-orientedness of the research……………………………………………….42 2.3. Participatory observation………………………………………………………...43 2.4. The dimensions of interpretations presented in the thesis ………………………44 3. Case-study of the socialization of Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)………………………………46 3.1. General methods of socialization………………………………………………..46 3.1.1. -

Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us About Human Language?

Linguistic Frontiers • 1(1) • 14-38 • 2018 DOI: 10.2478/lf-2018-0005 Linguistic Frontiers Representational Systems in Zoosemiotics and Anthroposemiotics Part I: What Have the So- Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us about Human Language? Research Article Vilém Uhlíř* Theoretical and Evolutionary Biology, Department of Philosophy and History of Sciences. Charles University. Viničná 7, 12843 Praha 2, Czech Republic Received ???, 2018; Accepted ???, 2018 Abstract: This paper offers a brief critical review of some of the so-called “Talking Animals” projects. The findings from the projects are compared with linguistic data from Homo sapiens and with newer evidence gleaned from experiments on animal syntactic skills. The question concerning what had the so-called “Talking Animals” really done is broken down into two categories – words and (recursive) syntax. The (relative) failure of the animal projects in both categories points mainly to the fact that the core feature of language – hierarchical recursive syntax – is missing in the pseudo-linguistic feats of the animals. Keywords: language • syntax • representation • meta-representation • zoosemiotics • anthroposemiotics • talking animals • general cognition • representational systems • evolutionary discontinuity • biosemiotics © Sciendo 1. The “Talking Animals” Projects For the sake of brevity, I offer a greatly selective review of some of the more important “Talking Animals” projects. Please note that many omissions were necessary for reasons of space. The “thought climate” of the 1960s and 1970s was formed largely by the Skinnerian zeitgeist, in which it seemed possible to teach any animal to master any, or almost any, skill, including language. Perhaps riding on an ideological wave, following the surprising claims of Fossey [1] and Goodall [2] concerning primates, as well as the claims of Lilly [3] and Batteau and Markey [4] concerning dolphins, many scientists and researchers focussed on the continuities between humans and other species, while largely ignoring the discontinuities and differences. -

Biosemiotic Medicine: from an Effect-Based Medicine to a Process-Based Medicine

Special article Arch Argent Pediatr 2020;118(5):e449-e453 / e449 Biosemiotic medicine: From an effect-based medicine to a process-based medicine Carlos G. Musso, M.D., Ph.D.a,b ABSTRACT Such knowledge evidences the Contemporary medicine is characterized by an existence of a large and intricate increasing subspecialization and the acquisition of a greater knowledge about the interaction among interconnected network among the the different body structures (biosemiotics), different body structures, which both in health and disease. This article proposes accounts for a sort of “communication a new conceptualization of the body based on channel” among its elements, a true considering it as a biological space (cells, tissues, and organs) and a biosemiotic space (exchange of “dialogic or semiotic space” that is signs among them). Its development would lead conceptually abstract but experientially to a new subspecialty focused on the study and real, through which normal and interference of disease biosemiotics (biosemiotic pathological intra- and inter- medicine), which would trigger a process- based medicine centered on early diagnosis and parenchymal dialogs (sign exchange) management of disease. occur. Such dialogs determine a Key words: medicine, biosemiotics, diagnosis, balanced functioning of organ systems therapy. or the onset and establishment of http://dx.doi.org/10.5546/aap.2020.eng.e449 disease, respectively. The investigation and analysis of such phenomenon is the subject of a relative new discipline: To cite: Musso CG. Biosemiotic medicine: From an biosemiotics, which deals with the effect-based medicine to a process-based medicine. 1 Arch Argent Pediatr 2020;118(5):e449-e453. study of the natural world’s language. -

Peirce's Theory of Communication and Its Contemporary Relevance

Ahti-Veikko Pietarinen Peirce’s Theory of Communication and Its Contemporary Relevance Introduction The mobile era of electronic communication has created a huge semi- otic system, constructed out of triadic components envisaged by the American scientist and philosopher Charles S. Peirce (1839–1914), such as icons, indices and symbols, and signs, objects and interpretants. Iconic signs bear a physical resemblance to what they represent. Indices point at something and say “there!”, and symbols signify objects by conven- tions of a community.1 All signs give rise to interpretants in the minds of the interpreters. It is nonetheless regrettable that the somewhat simplistic triadic ex- posé of Peirce’s theory of signs has persisted in semiotics as the some- how exhaustive and final description of what Peirce intended. The more fascinating and richer structure of signs emerging from their intimate relation to intercommunication and interaction (Peirce’s terms) has been noted much less frequently. Despite this shortcoming, the full Peircean road to inquiry – per- formed by the dynamic community of learning inquirers, or the com- 1 In fact, according to Peirce (2.278 [1895]): “The only way of directly communi- cating an idea is by means of an icon; and every indirect method of communicating an idea must depend for its establishment upon the use of an icon.” Peirce’s chef d’œuvre came shortly after these remarks into being as his diagrammatic system of existential graphs, a thoroughly iconic representation of and a way of reasoning about “moving pictures of thought”, which encompassed not only propositional and predicate logic, but also modalities, higher-order notions, abstraction and category-theoretic notions. -

Semiowild.Pdf

SEMIOTICS IN THE WILD ESYS A S IN HONOUR OF KALEVI KULL ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 60TH BIRTHDAY Semiotics in the Wild Essays in Honour of Kalevi Kull on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday Edited by Timo Maran, Kati Lindström, Riin Magnus and Morten Tønnessen Illustrations: Aleksei Turovski Cover: Kalle Paalits Layout: Kairi Kullasepp ISBN 978–9949–32–041–7 © Department of Semiotics at the University of Tartu © Tartu University Press © authors Tartu 2012 CONTENTS 7 Kalevi Kull and the rewilding of biosemiotics. Introduction Kati Lindström, Riin Magnus, Timo Maran and Morten Tønnessen 15 Introducing a new scientific term for the study of biosemiosis Donald Favareau 25 Are we cryptos? Anton Markoš 31 Trolling and strolling through ecosemiotic realms Myrdene Anderson 39 Long live the homunculus! Some thoughts on knowing Yair Neuman 47 Introducing semetics Morten Tønnessen 55 Peirce’s ten classes of signs: Modeling biosemiotic processes and systems João Queiroz 36 The origin of mind Alexei A. Sharov 71 Is semiosis one of Darwin’s “several powers”? Terrence W. Deacon 79 Dicent symbols in mimicry João Queiroz, Frederik Stjernfelt and Charbel Niño El-Hani 87 A contribution to theoretical ecology: The biosemiotic perspective Almo Farina 95 Ecological anthropology, Actor Network Theory and the concepts of nature in a biosemiotics based on Jakob von Uexküll’s Umweltlehre Søren Brier 103 Life, lives: Mikhail Bakhtin, Ivan Kanaev, Hans Driesch, Jakob von Uexküll Susan Petrilli and Augusto Ponzio 117 Smiling snails: on semiotics and poetics of academic -

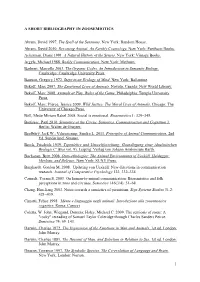

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Politeness in Japanese Sign Language (JSL): Polite JSL Expression as Evidence for Intermodal Language Contact Influence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4jq1v247 Author George, Johnny Publication Date 2011 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Politeness in Japanese Sign Language (JSL): Polite JSL expression as evidence for intermodal language contact influence By Johnny Earl George A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in LINGUISTICS in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve Sweetser, Chair Professor Sharon Inkelas Professor Yoko Hasegawa Fall 2011 Politeness in Japanese Sign Language (JSL): Polite JSL expression as evidence for intermodal language contact influence © 2011 by Johnny Earl George 1 ABSTRACT Politeness in Japanese Sign Language (JSL): Polite JSL expression as evidence for intermodal language contact influence by Johnny Earl George Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve Sweetser, Chair This dissertation shows how signers mark polite register in JSL and uncovers a number of features salient to the linguistic encoding of politeness. My investigation of JSL politeness considers the relationship between Japanese sign and speech and how users of these languages adapt their communicative style based on the social context. This work examines: the Deaf Japanese community as minority language users and the concomitant effects on the development of JSL; politeness in JSL independently and in relation to spoken Japanese, along with the subsequent implications for characterizing polite Japanese communicative interaction; and the results of two studies that provide descriptions of the ways in which JSL users linguistically encode polite register. -

Hypertext Semiotics in the Commercialized Internet

Hypertext Semiotics in the Commercialized Internet Moritz Neumüller Wien, Oktober 2001 DOKTORAT DER SOZIAL- UND WIRTSCHAFTSWISSENSCHAFTEN 1. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Wolfgang Panny, Institut für Informationsver- arbeitung und Informationswirtschaft der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien, Abteilung für Angewandte Informatik. 2. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dr. Herbert Hrachovec, Institut für Philosophie der Universität Wien. Betreuer: Gastprofessor Univ. Doz. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Veith Risak Eingereicht am: Hypertext Semiotics in the Commercialized Internet Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Sozial- und Wirtschaftswissenschaften an der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien eingereicht bei 1. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Panny, Institut für Informationsverarbeitung und Informationswirtschaft der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien, Abteilung für Angewandte Informatik 2. Beurteiler: Univ. Prof. Dr. Herbert Hrachovec, Institut für Philosophie der Universität Wien Betreuer: Gastprofessor Univ. Doz. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Veith Risak Fachgebiet: Informationswirtschaft von MMag. Moritz Neumüller Wien, im Oktober 2001 Ich versichere: 1. daß ich die Dissertation selbständig verfaßt, andere als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel nicht benutzt und mich auch sonst keiner unerlaubten Hilfe bedient habe. 2. daß ich diese Dissertation bisher weder im In- noch im Ausland (einer Beurteilerin / einem Beurteiler zur Begutachtung) in irgendeiner Form als Prüfungsarbeit vorgelegt habe. 3. daß dieses Exemplar mit der beurteilten Arbeit überein -

A Semiotic Theory of Music: According to a Peircean Rationale

A SEMIOTIC THEORY OF MUSIC: ACCORDING TO A PEIRCEAN RATIONALE The Sixth International Conference on Musical Signification University of Helsinki Université de Provence (Aix-Marselle I) Aix-en-Provence, December 1-5, 1998 José Luiz Martinez (Ph.D.) [1] The recent growth of musical applications of Peirce’s general theory of signs, such as in the works of David Lidov (1986), Robert Hatten (1994), William Dougherty (1993, 1994), shows that this approach, once set properly in both musical and semiotic contexts, has great analytical power on questions of musical signification. In this paper I will present the structure of a semiotic theory of music, as demonstrated in my doctoral dissertation, Semiosis in Hindustani Music (Imatra: International Semiotics Institute), submitted and approved by the University of Helsinki in 1997. [2] Peirce, in his studies of semiotics, concluded that thought is only possible by means of signs (vide CP 1.538, 4.551, 5.253). Music is a species of thought; and thus, the idea that music is sign and depends on significative processes, or semiosis, is obviously true. A musical sign can be a system, a composition or its performance, a musical form, a style, a composer, a musician, hers or his instrument, and so on. According to Peirce, signification occurs in a triadic relation of a sign and the object it stands for to an interpretant (CP 6.347), which - in music - is another sign developed in the mind of a listener, musician, composer, analyst or critic. [3] In Peirce’s classification of the sciences, semiotics (or semeiotic) has three branches: Speculative Grammar, Critic and Methodeutic (or Speculative Rhetoric) (CP 1.192). -

Download Download

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Journals from University of Tartu 452 Kalevi Kull Sign Systems Studies 46(4), 2018, 452–466 Choosing and learning: Semiosis means choice Kalevi Kull Department of Semiotics University of Tartu, Jakobi 2, 51005 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. We examine the possibility of shift ing the concept of choice to the centre of the semiotic theory of learning. Th us, we defi ne sign process (meaning-making) through the concept of choice: semiosis is the process of making choices between simultaneously provided options. We defi ne semiotic learning as leaving traces by choices, while these traces infl uence further choices. We term such traces of choices memory. Further modifi cation of these traces (constraints) will be called habituation. Organic needs are homeostatic mechanisms coupled with choice-making. Needs and habits result in motivatedness. Semiosis as choice-making can be seen as a complementary description of the Peircean triadic model of semiosis; however, this can fi t also the models of meaning-making worked out in other shools of semiotics. We also provide a sketch for a joint typology of semiosis and learning. Keywords: biosemiotics; decision-making; free choice; general semiotics; homeostasis; need; non-algorithmicity; nowness; post-Darwinism; semiotic quanta; sign typology; types of learning Der Lebensvorgang ist nicht eine Sukzession von Ursache und Wirkung, sondern eine Entscheidung.1 Viktor von Weizsäcker (1940: 126) It would be foolish to claim that one can tackle this topic and expect to be satisfi ed. -

Review: Marcello Barbieri (Ed) (2007) Introduction to Biosemiotics. the New Biological Synthesis

tripleC 5(3): 104-109, 2007 ISSN 1726-670X http://tripleC.uti.at Review: Marcello Barbieri (Ed) (2007) Introduction to Biosemiotics. The new biological synthesis. Dordrecht: Springer Günther Witzany telos – Philosophische Praxis Vogelsangstr. 18c A-5111-Buermoos/Salzburg Austria E-mail: [email protected] 1 Thematic background without utterances we act as non-uttering indi- viduals being dependent on the discourse de- Maybe it is no chance that the discovery of the rived meaning processes of a linguistic (e.g. sci- genetic code occurred during the hot phase of entific) community. philosophy of science discourse about the role of This position marks the primary difference to language in generating models of scientific ex- the subject of knowledge of Kantian knowledge planation. The code-metaphor was introduced theories wherein one subject alone in principle parallel to other linguistic terms to denote lan- could be able to generate sentences in which it guage like features of the nucleic acid sequence generates knowledge. This abstractive fallacy molecules such as “code without commas” was ruled out in the early 50s of the last century (Francis Crick). At the same time the 30 years of being replaced by the “community of investiga- trying to establish an exact scientific language to tors” (Peirce) represented by the scientific com- delimit objective sentences from non-objective munity in which every single scientist is able the ones derived one of his peaks in the linguistic place his utterance looking for being integrated turn. in the discourse community in which his utter- ances will be proven whether they are good ar- 1.1 Changing subjects of knowledge guments or not. -

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA Qualia (singular, quale) are cultural emergents that manifest phenomenally as sensuous features or qualities. The anthropological challenge presented by qualia is to theorize elements of experience that are semiotically generated but apperceived as non-signs. Qualia are not reducible to a psychology of individual perceptions of sensory data, to a cultural ontology of “materiality,” or to philosophical intuitions about the subjective properties of consciousness. The analytical solution to the challenge of qualia is to con- sider tone in relation to the familiar linguistic anthropological categories of token and type. This solution has been made methodologically practical by conceptualizing qualia, in Peircean terms, as “facts of firstness” or firstness “under its form of secondness.” Inthephilosophyofmind,theterm“qualia”hasbeenusedtodescribetheineffable, intrinsic, private, and directly or immediately apprehensible experiences of “the way things seem,” which have been taken to constitute the atomic subjective properties of consciousness. This concept was challenged in an influential paper by Daniel Dennett, who argued that qualia “is a philosophers’ term which fosters nothing but confusion, and refers in the end to no properties or features at all” (Dennett 1988, 387). Dennett concluded, correctly, that these diverse elements of feeling, made sensuously present atvariouslevelsofattention,wereactuallyidiosyncraticresponsestoapperceptions of “public, relational” qualities. Qualia were, in effect,