Neglected Aspects of Peirce's Writings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja the ZOOSEMIOTICS of SOCIALIZATION

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja THE ZOOSEMIOTICS OF SOCIALIZATION: CASE-STUDY IN SOCIALIZING RED FOX (VULPES VULPES) IN TANGEN ANIMAL PARK, NORWAY Master’s Thesis Supervisors: Timo Maran, Ph.D Nelly Mäekivi, M.A Tartu 2014 CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….4 1. The theoretical aspects of keeping wild animals in captivity ………………………………7 1.1. The main arguments on the ethics of keeping animals in captivity……………….7 1.2. Modern viewpoints on animal welfare……………………………………………9 1.3. Modern viewpoints on animal behaviour………………………………………..13 1.3.1. Behavioural display and animal welfare……………………………….14 1.4. The role of enrichment in animal welfare………………………………………..17 1.4.1. The essence of animal training in zoos………………………………...19 1.5. The importance of human-animal relationships in the zoo………………………21 1.5.1. The importance of Umwelt consideration……………………………...23 1.5.1.1. The functional circle ………………………………………...24 1.5.2. The effect of zoo visitors on animal welfare…………………………..26 1.5.3. The effect of keeper-animal relationships on animal welfare………….28 1.6. Explaining animal communication…………………………………………........30 1.7. Socialization – a method of improving welfare of captive animals……………...36 1.7.1. The need for socialization……………………………………………...37 1.7.2. The basic mechanisms of socialization………………………………...38 2. The research methodology of a zoosemiotic approach to socialization …………………...40 2.1. Thick description of socialization………………………………………………..40 2.2. Actor-orientedness of the research……………………………………………….42 2.3. Participatory observation………………………………………………………...43 2.4. The dimensions of interpretations presented in the thesis ………………………44 3. Case-study of the socialization of Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)………………………………46 3.1. General methods of socialization………………………………………………..46 3.1.1. -

Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us About Human Language?

Linguistic Frontiers • 1(1) • 14-38 • 2018 DOI: 10.2478/lf-2018-0005 Linguistic Frontiers Representational Systems in Zoosemiotics and Anthroposemiotics Part I: What Have the So- Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us about Human Language? Research Article Vilém Uhlíř* Theoretical and Evolutionary Biology, Department of Philosophy and History of Sciences. Charles University. Viničná 7, 12843 Praha 2, Czech Republic Received ???, 2018; Accepted ???, 2018 Abstract: This paper offers a brief critical review of some of the so-called “Talking Animals” projects. The findings from the projects are compared with linguistic data from Homo sapiens and with newer evidence gleaned from experiments on animal syntactic skills. The question concerning what had the so-called “Talking Animals” really done is broken down into two categories – words and (recursive) syntax. The (relative) failure of the animal projects in both categories points mainly to the fact that the core feature of language – hierarchical recursive syntax – is missing in the pseudo-linguistic feats of the animals. Keywords: language • syntax • representation • meta-representation • zoosemiotics • anthroposemiotics • talking animals • general cognition • representational systems • evolutionary discontinuity • biosemiotics © Sciendo 1. The “Talking Animals” Projects For the sake of brevity, I offer a greatly selective review of some of the more important “Talking Animals” projects. Please note that many omissions were necessary for reasons of space. The “thought climate” of the 1960s and 1970s was formed largely by the Skinnerian zeitgeist, in which it seemed possible to teach any animal to master any, or almost any, skill, including language. Perhaps riding on an ideological wave, following the surprising claims of Fossey [1] and Goodall [2] concerning primates, as well as the claims of Lilly [3] and Batteau and Markey [4] concerning dolphins, many scientists and researchers focussed on the continuities between humans and other species, while largely ignoring the discontinuities and differences. -

Dialogism and Biosemiotics

Dialogism and biosemiotics AUGUSTO PONZIO The notions of ‘modeling’ and ‘interrelation’ play a pivotal role in Sebeok’s biosemiotics. In dialogue with Thomas A. Sebeok’s doctrine of signs, we propose to inquire into the action of modeling and interrelation in biosemiosis over the planet Earth, developing the concept of interrelation in terms of ‘dialogism’. Indeed, in the light of Sebeok’s biosemiotics we believe that the concept of dialogism may be extended beyond the sphere of anthroposemiosis and applied to all communication processes, which may be described as being grounded not only in the concept of modeling, but also in that of dialogism. And remembering that the concept of dialogue is fundamental in Charles S. Peirce’s thought system, we also propose that the approach we are formulating be viewed as an attempt at developing the Peircean matrix of biosemiotics. Modeling systems theory and global semiotics ‘Modeling’ and ‘interrelation’ among species-specific semioses over the entire planet Earth are two issues that Thomas A. Sebeok’s puts at the center of his ‘doctrine of signs’ — the expression he prefers to ‘science of signs’ or ‘theory of signs’. The present paper focuses on these two topics developing them in the light of our own personal perspective. The term ‘dialogism’ in the present paper designates a development with respect to the condition of interrelation in global semiosis, as described by Sebeok. In our opinion modeling and dialogism are the basis of all communication processes. Another pivotal topic in Sebeok’s ‘doctrine of signs’ is his belief that humans alone are capable of ‘semiotics’, that is, of consciousness, of what we may designate as ‘metasemiosis’, the capacity to suspend the immediacy of semiosic activity and deliberate. -

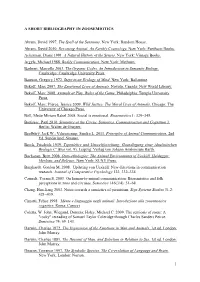

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Politeness in Japanese Sign Language (JSL): Polite JSL Expression as Evidence for Intermodal Language Contact Influence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4jq1v247 Author George, Johnny Publication Date 2011 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Politeness in Japanese Sign Language (JSL): Polite JSL expression as evidence for intermodal language contact influence By Johnny Earl George A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in LINGUISTICS in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve Sweetser, Chair Professor Sharon Inkelas Professor Yoko Hasegawa Fall 2011 Politeness in Japanese Sign Language (JSL): Polite JSL expression as evidence for intermodal language contact influence © 2011 by Johnny Earl George 1 ABSTRACT Politeness in Japanese Sign Language (JSL): Polite JSL expression as evidence for intermodal language contact influence by Johnny Earl George Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve Sweetser, Chair This dissertation shows how signers mark polite register in JSL and uncovers a number of features salient to the linguistic encoding of politeness. My investigation of JSL politeness considers the relationship between Japanese sign and speech and how users of these languages adapt their communicative style based on the social context. This work examines: the Deaf Japanese community as minority language users and the concomitant effects on the development of JSL; politeness in JSL independently and in relation to spoken Japanese, along with the subsequent implications for characterizing polite Japanese communicative interaction; and the results of two studies that provide descriptions of the ways in which JSL users linguistically encode polite register. -

Augusto Ponzio: a Brief Note on the “Italian Bakhtin”

Marcel Danesi AUGUSTO PONZIO: A BRIEF NOTE ON THE “ITALIAN BAKHTIN” 1. Introduction The link between dialogue and knowledge was established in the ancient world by the great teachers and philosophers of that world, from China to the Middle East, from north to south, east to west. It is probably the oldest implicit principle in history of how we gain understanding, and its validity is evidenced by the fact that it is still part of education and most forms of philosophical inquiry in all parts of the world today. Studying what dialogue is, therefore, is no trivial matter, if indeed it constitutes a powerful format for the construction, discovery, and acquisition of knowledge. It was used by Socrates, after all, in the form of a question-and-answer exchange as a means for achieving self-knowledge. Socrates believed in the superiority of dialectic argument over writing, spending hours in the public places of Athens, and engaging in dialogue and argument with anyone who would listen. The so-called “Socratic method” is still as valid today as it was then, betraying the implicit view that it is only through the humility that comes through dialogue that it becomes possible to grasp truths about the world. Through dialogue, in fact, we come to understand our own ignorance, which entices us forward to investigate something further. There really is no other path to understanding than the dialogic one – so it would seem. The modern-day intellectual who certainly understood this like very few others of his era was the late Russian philosopher and literary scholar Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1975). -

Problems of Language in Welby's Significs

Problems of Language in Welby's Significs Introduction The term "significs" was coined by Victoria Lady Welby (1837-1912) toward the end of the last century to designate the particular bend she wished to confer on her studies on signs and meaning. Significs trascends pure descriptivism and emerges as a method for the analysis of sign activity, beyond logico-gnoseological boundaries, and, therefore, for the evaluation of signs in their ethical, esthetic and pragmatic dimensions. To carry out her work Welby was convinced that the instrument at her disposal, verbal language, should be in perfect working order. Consequently, the problem of reflecting on language and meaning in general immediately took on a double aspect as it also surfaced in her mind as the problem of the condition of the specific language through which she was thinking. After her death Welby was very quickly forgotten as an intellectual and until recent times, if she was ever remembered it was as Charles S. Peirces correspondent and not necessarily in her own right as the ideator of significs. Her influence has gone largely unnoticed having been most often than not unrecognized. In addition to her publications, Welby was in the habit of discussing her ideas in her letters and to this end corresponded with numerous intellectuals, many of whom she knew personally, including a part from Peirce, M. Bréal, B. Russell, H. and W. James, H. Bergson, R. Carnap, A. Lalande, F. Pollock, G.F. Stout, F.C.S. Schiller and C.K. Ogden, G. Vailati, M. Calderoni and many others. Ogden promoted significs as a university student during the years 1910- 1911, and contrihuted to spreading Welby's ideas. -

Review: Marcello Barbieri (Ed) (2007) Introduction to Biosemiotics. the New Biological Synthesis

tripleC 5(3): 104-109, 2007 ISSN 1726-670X http://tripleC.uti.at Review: Marcello Barbieri (Ed) (2007) Introduction to Biosemiotics. The new biological synthesis. Dordrecht: Springer Günther Witzany telos – Philosophische Praxis Vogelsangstr. 18c A-5111-Buermoos/Salzburg Austria E-mail: [email protected] 1 Thematic background without utterances we act as non-uttering indi- viduals being dependent on the discourse de- Maybe it is no chance that the discovery of the rived meaning processes of a linguistic (e.g. sci- genetic code occurred during the hot phase of entific) community. philosophy of science discourse about the role of This position marks the primary difference to language in generating models of scientific ex- the subject of knowledge of Kantian knowledge planation. The code-metaphor was introduced theories wherein one subject alone in principle parallel to other linguistic terms to denote lan- could be able to generate sentences in which it guage like features of the nucleic acid sequence generates knowledge. This abstractive fallacy molecules such as “code without commas” was ruled out in the early 50s of the last century (Francis Crick). At the same time the 30 years of being replaced by the “community of investiga- trying to establish an exact scientific language to tors” (Peirce) represented by the scientific com- delimit objective sentences from non-objective munity in which every single scientist is able the ones derived one of his peaks in the linguistic place his utterance looking for being integrated turn. in the discourse community in which his utter- ances will be proven whether they are good ar- 1.1 Changing subjects of knowledge guments or not. -

Accomplishing Identity in Participant-Denoting Discourse Stanton Wortham University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarlyCommons@Penn University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons GSE Publications Graduate School of Education January 2003 Accomplishing Identity in Participant-Denoting Discourse Stanton Wortham University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs Recommended Citation Wortham, S. (2003). Accomplishing Identity in Participant-Denoting Discourse. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/ gse_pubs/50 Published as Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, Volume 13, Issue 2, 2003, pages 189-210. © 2003 by the Regents of the University of California/ American Anthropological Association. Copying and permissions notice: Authorization to copy this content beyond fair use (as specified in Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law) for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by the Regents of the University of California/on behalf of the American Anthropological Association for libraries and other users, provided that they are registered with and pay the specified fee via Rightslink® on Caliber (http://caliber.ucpress.net/)/AnthroSource (http://www.anthrosource.net) or directly with the Copyright Clearance Center, (http://www.copyright.com ). This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/50 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Accomplishing Identity in Participant-Denoting Discourse Abstract Individuals become socially identified when categories of identity are used repeatedly to characterize them. Speech that denotes participants and involves parallelism between descriptions of participants and the events that they enact in the event of speaking can be a powerful mechanism for accomplishing consistent social identification. -

Semiotics and Contemporary Play Directing: the Example of Ogonna Agu’S Dawn in the Academy

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 16, No. 3, 2020, pp. 57-62 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/11746 www.cscanada.org Semiotics and Contemporary Play Directing: The Example of Ogonna Agu’s Dawn in the Academy Affiong Fred Effiom[a],* [a]Department of Theatre, Film and Carnival Studies, University of Effiom, A. F. (2020). Semiotics and Contemporary Play Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria. Directing: The Example of Ogonna Agu’s Dawn in the Academy. *Corresponding author. Cross-Cultural Communication, 16(3), 57-62. Available from: http//www.cscanada.net/index.php/ccc/article/view/11746 Received 3 August 2020; accepted 1 September 2020 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3968/11746 Published online 26 September 2020 Abstract The success of any theatrical performance depends INTRODUCTION largely on how the theatre director understands, A study of the major styles, concepts and approaches experiments and explores the wide array of techniques in theatre reveal a preponderance of techniques and and approaches for creating such theatrical production. diverse method of theatrical presentation. More so, with This inquiry experimented on the semiotic theory, a the preoccupation of the modern theatre practitioner, 21st century postmodern experimental form, as an whose essence consists in varied experimentations approach to creating a theatrical production. The play carried out either by projecting old concepts, question script Dawn in the Academy was semiotically analyzed certain phenomena or tenets of existing movements. This and presented from a directorial perspective on the stage development had no doubt, characterized contemporary of Chinua Achebe Arts Theatre, University of Calabar, theatre and set its dynamism along a transient path. -

Umberto Eco on the Biosemiotics of Giorgio Prodi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Journals from University of Tartu 352 Kalevi Kull Sign Systems Studies 46(2/3), 2018, 352–364 Umberto Eco on the biosemiotics of Giorgio Prodi Kalevi Kull Department of Semiotics University of Tartu Jakobi 2, Tartu 51005, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The article provides a commentary on Umberto Eco’s text “Giorgio Prodi and the lower threshold of semiotics”. An annotated list of Prodi’s English-language publications on semiotics is included. Keywords: history of biosemiotics; lower semiotic threshold; medical semiotics Biology is pure natural semiotics. Prodi 1986b: 122 Is it by law or by nature that the image of Mickey Mouse reminds us of a mouse? Eco 1999: 339 “When I discovered the research of Giorgio Prodi on biosemiotics I was the person to publish his book that maybe I was not in total agreement with, but I found it was absolutely important to speak about those things”, Umberto Eco said during our conversation in Milan in 2012. Indeed, two books by Prodi – Orizzonti della genetica (Prodi 1979; series Espresso Strumenti) and La storia naturale della logica (Prodi 1982; series Studi Bompiani: Il campo semiotico) – appeared in series edited by Eco. Giorgio Prodi was a biologist whom Eco highly valued, an expert and an encyclopedia for him in the fields of biology and medicine, a scholar whose work in biosemiotics Eco took very seriously. Eco spoke about this in a talk from 1988 (Eco 2018), saying that he had been suspicious of semiotic approaches to cells until he met Prodi in 1974. -

Semiosphere As a Model of Human Cognition

494 Aleksei Semenenko Sign Systems Studies 44(4), 2016, 494–510 Homo polyglottus: Semiosphere as a model of human cognition Aleksei Semenenko Department of Slavic and Baltic Languages Stockholm University 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Th e semiosphere is arguably the most infl uential concept developed by Juri Lotman, which has been reinterpreted in a variety of ways. Th is paper returns to Lotman’s original “anthropocentric” understanding of semiosphere as a collective intellect/consciousness and revisits the main arguments of Lotman’s discussion of human vs. nonhuman semiosis in order to position it in the modern context of cognitive semiotics and the question of human uniqueness in particular. In contrast to the majority of works that focus on symbolic consciousness and multimodal communication as specifi cally human traits, Lotman accentuates polyglottism and dialogicity as the unique features of human culture. Formulated in this manner, the concept of semiosphere is used as a conceptual framework for the study of human cognition as well as human cognitive evolution. Keywords: semiosphere; cognition; polyglottism; dialogue; multimodality; Juri Lotman Th e concept of semiosphere is arguably the most infl uential concept developed by the semiotician and literary scholar Juri Lotman (1922–1993), a leader of the Tartu- Moscow School of Semiotics and a founder of semiotics of culture. In a way, it was the pinnacle of Lotman’s lifelong study of culture as an intrinsic component of human individual