The Basque Government's Post-Franco Discourses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Between Accommodation and Secession: Explaining the Shifting Territorial Goals of Nationalist Parties in the Basque Country and Catalonia

Between accommodation and secession: Explaining the shifting territorial goals of nationalist parties in the Basque Country and Catalonia Anwen Elias Reader at Department of International Politics, Aberystwyth University Email: [email protected] Ludger Mees Full Professor at Department of Contemporary History, University of the Basque Country Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article examines the shifting territorial goals of two of the most electoral- ly successful and politically relevant nationalist parties in Spain: the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (PNV) and Convergència i Unió (CiU). Whilst both parties have often co-operated to challenge the authority of the Spanish state, their territorial goals have varied over time and from party to party. We map these changes and identify key drivers of territorial preferences; these include party ideology, the impact of the financial crisis, the territorial structure of the state, party competition, public opinion, government versus opposition, the impact of multi-level politics and the particularities of party organisation. These factors interact to shape what nationalist parties say and do on core territorial issues, and contribute to their oscillation between territorial accommodation and secession. However, the way in which these factors play out is highly context-specific, and this accounts for the different territorial preferences of the PNV and CiU. These findings advance our understanding of persistent territorial tensions in Spain, and provide broader theoretical insights into the internal and external dynamics that determine the territorial positioning of stateless nationalist and regionalist parties in plurinational states. KEYWORDS Spain; Basque Country; Catalonia; territorial goals; party strategies; nation- alism; regional autonomy. Article received on 04/10/2016, approved on 17/03/2017. -

Basque Plan for Culture Basque Plan for Culture

Cubierta EN 11/4/05 10:04 Pagina 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Basque Plan for Culture Basque Plan for Culture ISBN 84-457-2264-6 Salneurria / P.V.P.: 8 € Price: 5,57 £ KULTURA SAILA DEPARTAMENTO DE CULTURA Compuesta BASQUE PLAN FOR CULTURE KULTURA SAILA DEPARTAMENTO DE CULTURA Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco Vitoria-Gasteiz, 2005 Basque plan for culture. – 1st ed. – Vitoria-Gasteiz : Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia = Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, 2005 p. ; cm. + 1 CD-ROM ISBN 84-457-2264-6 1. Euskadi-Política cultural. I. Euskadi. Departamento de Cultura. 32(460.15):008 Published: 1st edition, april 2005 Print run: 500 © Euskal Autonomia Erkidegoko Administrazioa Kultura Saila Administración de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco Departamento de Cultura Internet: www.euskadi.net Published by: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco Donostia-San Sebastián, 1 – 01010 Vitoria-Gasteiz Photosetting: Rali, S.A. – Bilbao Printed by: Estudios Gráficos Zure, S.A. – Bilbao ISBN: 84-457-2264-6 L.D.: BI-830-05 Contents PROLOGUE . 7 PRESENTATION . 9 1. CULTURAL AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK . 13 1.1. A broad vision of culture . 15 1.1.1. Culture, heterogeneity and integration . 15 1.1.2. Culture and identity . 15 1.1.3. Culture and institutions . 16 1.1.4. Culture and economy . 16 1.1.5. Basque culture in the broad sense . 17 1.2. The Basque cultural system . 17 1.2.1. Cultural and communicative space . 17 1.2.2. -

The Lehendakari

E.ETXEAK montaje ENG 3/5/01 16:08 P‡gina 1 Issue 49 YEAR 2001 TheThe LehendakariLehendakari callscalls forfor anan electionelection inin thethe BasqueBasque CountryCountry onon MayMay 13th13th E.ETXEAK montaje ENG 4/5/01 08:53 P‡gina 2 Laburpena SUMMARY Laburpena SUMMARY EDITORIALA■EDITORIAL – Supplementary statement to the Decree dissolving Parliament ...................... 3 GAURKO GAIAK■CURRENT EVENTS – Instructions for voting by mail .................................................................................. 5 – Basque election predictions according to surveys................................................ 6 PERTSONALITATEAK■PERSONALITIES – The Sabino Arana Awards for the year 2000........................................................ 8 EUSKAL ETXEAK – The Human Rights Commissioner visited the Basque Country ....................... 8 ISSUE 49 - YEAR 2001 URTEA – Francesco Cossiga received the "Lagun Onari" honor ...................................... 9 EGILEA AUTHOR Eusko Jaurlaritza-Kanpo – The Government of Catalonia receives part of its history Harremanetarako Idazkaritza Nagusia from the Sabino Arana Foundation ....................................................................... 10 Basque Government-Secretary General for Foreign Action – The Secretary of State of Idaho calls for the U.S. C/ Navarra, 2 to mediate in the Basque Country......................................................................... 11 01007 VITORIA-GASTEIZ Phone: 945 01 79 00 ■ [email protected] ERREPORTAIAK ARTICLES ZUZENDARIA DIRECTOR – The -

Anuario Del Seminario De Filología Vasca «Julio De Urquijo» International Journal of Basque Linguistics and Philology

ANUARIO DEL SEMINARIO DE FILOLOGÍA VASCA «Julio DE URQUIJo» International Journal of Basque Linguistics and Philology LIII (1-2) 2019 [2021] ASJU, 2019, 53 (1-2), 1-38 https://doi.org/10.1387/asju.22410 ISSN 0582-6152 – eISSN 2444-2992 Luis Michelena (Koldo Mitxelena) y la creación del Seminario de Filología Vasca «Julio de Urquijo» 1 (1947-1956)1 Luis Michelena (Koldo Mitxelena) and the founding of the «Julio de Urquijo» Basque Philology Seminar (1947-1956) Antón Ugarte Muñoz* ABSTRACT: We are presenting below the history of the founding of the «Julio de Urquijo» Basque Philology Seminar, created by the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa in 1953, whose tech- nical adviser and unofficial director was the eminent linguist Luis Michelena. KEYWORDS: Luis Michelena, Koldo Mitxelena, Basque studies, intellectual history. RESUMEN: Presentamos a continuación la historia de la fundación del Seminario de Filología Vasca «Julio de Urquijo», creado por la Diputación Provincial de Gipuzkoa en 1953, cuyo asesor téc- nico y director oficioso fue el eminente lingüista Luis Michelena. PALABRAS CLAVE: Luis Michelena, Koldo Mitxelena, estudios vascos, historia intelectual. 1 Una versión de este artículo fue presentada en las jornadas celebradas en Vitoria-Gasteiz (2019- 12-13) por el grupo Monumenta Linguae Vasconum de la UPV/EHU que dirigen los profesores Blanca Urgell y Joseba A. Lakarra, a quienes agradezco su invitación. El significado de las abreviaturas emplea- das se encuentra al final del texto. * Correspondencia a / Corresponding author: Antón Ugarte Muñoz. Etxague Jenerala, 14 (20003 Donostia/San Sebastián) – ugarte. [email protected] – https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0102-4472 Cómo citar / How to cite: Ugarte Muñoz, Antón (2021). -

El Caso Bildu: Un Supuesto De Extralimitación De

EL CASO BILDU: UN SUPUESTO DE EXTRALIMITACIÓN DE FUNCIONES DEL TRIBUNAL CONSTITUCIONAL Comentario de la Sentencia de la Sala Especial del Tribunal Supremo de 1 de mayo de 2011 y de la Sentencia del Tribunal Constitucional de 5 de mayo de 2011 JAVIER Tajadura Tejada I. Introducción.—II. LA SENTENCIA DE LA SALA ESPECIAL DEL Tribunal SUPREMO DE 1 DE MAYO DE 2011: 1. Las demandas de la Abogacía del Estado y del Ministerio Fiscal. 2. Las alegaciones de Bildu. 3. La fundamentación del fallo mayoritario de la Sala Especial: 3.1. Nor- mativa aplicable. 3.2. Análisis y valoración de la prueba. 3.3. Conclusiones. 3.4. El «contraindi- cio». 3.5. El principio de proporcionalidad. 4. Análisis del Voto particular.—III. LA SENTENCIA DEL Tribunal Constitucional DE 5 DE MAYO DE 2011: 1. La fundamentación del recurso de amparo. 2. Las alegaciones de la Abogacía del Estado y del Ministerio Fiscal. 3. Los Fundamen- tos Jurídicos de la sentencia. 4. El Voto particular del profesor Manuel Aragón.—IV. CONSIDE- raciones finales. I. Introducción El día 5 de mayo de 2011, por una exigua mayoría de seis votos frente a cinco, el Pleno del Tribunal Constitucional, tras una deliberación de urgencia de menos de cuatro horas, dictó una de las sentencias más importantes de toda su historia. En ella estimó el recurso de amparo de la coalición electoral Bildu contra la sentencia de la Sala Especial del Tribunal Supremo que cuatro días atrás había anulado todas las candidaturas presentadas a los comicios del 22 de mayo. Desde el punto de vista jurídico, la principal objeción que cabe formular a esta sentencia es la de haberse extralimitado en sus funciones y haber invadido, de forma clara y notoria, el ámbito competencial propio del Tribunal Supremo. -

Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Center welcomes Gloria Totoricagüena New faculty member Gloria Totoricagüena started to really compare and analyze their FALL began working at the Center last spring, experiences, to look at the similarities and having recently completed her Ph.D. in differences between that Basque Center and 2002 Comparative Politics. Following is an inter- Basque communities in the U.S. So that view with Dr. Totoricagüena by editor Jill really started my academic interest. Al- Berner. though my Master’s degree was in Latin American politics and economic develop- NUMBER 66 JB: How did your interest in the Basque ment, the experience there gave me the idea diaspora originate and develop? GT: I really was born into it, I’ve lived it all my life. My parents are survivors of the In this issue: bombing of Gernika and were refugees to different parts of the Basque Country. And I’ve also lived the whole sheepherder family Gloria Totoricagüena 1 experience that is so common to Basque identity in the U.S. My father came to the Eskerrik asko! 3 U.S. as a sheepherder, and then later went Slavoj Zizek lecture 4 back to Gernika where he met my mother and they married and came here. My parents went Politics after 9/11 5 back and forth actually, and eventually settled Highlights in Boise. So this idea of transnational iden- 6 tity, and multiculturalism, is not new at all to Visiting scholars 7 me. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Basque Studies

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Basque Literature Series launched at Frankfurt Book Fair FALL Reported by Mari Jose Olaziregi director of Literature across Frontiers, an 2004 organization that promotes literature written An Anthology of Basque Short Stories, the in minority languages in Europe. first publication in the Basque Literature Series published by the Center for NUMBER 70 Basque Studies, was presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair October 19–23. The Basque Editors’ Association / Euskal Editoreen Elkartea invited the In this issue: book’s compiler, Mari Jose Olaziregi, and two contributors, Iban Zaldua and Lourdes Oñederra, to launch the Basque Literature Series 1 book in Frankfurt. The Basque Government’s Minister of Culture, Boise Basques 2 Miren Azkarate, was also present to Kepa Junkera at UNR 3 give an introductory talk, followed by Olatz Osa of the Basque Editors’ Jauregui Archive 4 Association, who praised the project. Kirmen Uribe performs Euskal Telebista (Basque Television) 5 was present to record the event and Highlights 6 interview the participants for their evening news program. (from left) Lourdes Oñederra, Iban Zaldua, and Basque Country Tour 7 Mari Jose Olaziregi at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Research awards 9 Prof. Olaziregi explained to the [photo courtesy of I. Zaldua] group that the aim of the series, Ikasi 2005 10 consisting of literary works translated The following day the group attended the Studies Abroad in directly from Basque to English, is “to Fair, where Ms. Olaziregi met with editors promote Basque literature abroad and to and distributors to present the anthology and the Basque Country 11 cross linguistic and cultural borders in order discuss the series. -

Elko Jaietan 51 Urte Celebrating 51 Years of Basque Tradition Schedule of Events

2014 Elko Jaietan 51 Urte Celebrating 51 Years of Basque Tradition Schedule of Events 2014 Elko Jaietan 51 Urte 2014 Elko Basque Festival Celebrating 51 Years Friday July 4th/Ostirala 4an Uztaila 6:00 p.m. – Kickoff/Txupinazua- Elko Basque Clubhouse Enjoy the evening with your family and friends with a taste of what is to come during the weekend. There will be dancing by the Elko Ariñak dancers, a Paella contest, Basque sport exhibitions of weight lifting and wood chopping, and handball games. Stay for exceptional food, drink, bounce house, and a special performance by this year’s Udaleku group. Saturday July 5th/Larunbata 5an Uztaila 7:00 a.m. – 5K Run/Walk – Eusko Etxtea – Elko Basque Club- house $20 participation fee and you get a t-shirt Registration is at 6:15 a.m. Race starts at 7:00 a.m. For more information contact Cody Krenka at 738-6479 11:00 a.m. – Parade – Downtown Elko 1:00 p.m. - Games & Dancing – Elko County Fairgrounds $10 Adults $5 Children 12 & Under Featuring the following dance groups: Elko Ariñak, Utah’ko Triskalariak, Reno Zazpiak Bat, and Ardi Baltza. Watch traditional Basque rural sports featuring weightlifting, wood chopping, weight carrying, relay, tug o war, and more! 2 9 p.m. Dance - Eusko Etxea - Elko Basque Clubhouse $12 Admission Dance - featuring Boise’s Amuma Says No; come enjoy a fun filled evening of dancing, catching up with old friends and making new ones Sunday July 6th /Igandea 6an Uztaila Eusko Etxea - Elko Basque Clubhouse Please NO outside Food or Beverage 10:30 a.m. -

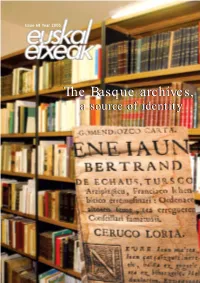

The Basquebasque Archives,Archives, Aa Sourcesource Ofof Identityidentity TABLE of CONTENTS

Issue 68 Year 2005 TheThe BasqueBasque archives,archives, aa sourcesource ofof identityidentity TABLE OF CONTENTS GAURKO GAIAK / CURRENT EVENTS: The Basque archives, a source of identity Issue 68 Year 3 • Josu Legarreta, Basque Director of Relations with Basque Communities. The BasqueThe archives,Basque 4 • An interview with Arantxa Arzamendi, a source of identity Director of the Basque Cultural Heritage Department 5 • The Basque archives can be consulted from any part of the planet 8 • Classification and digitalization of parish archives 9 • Gloria Totoricagüena: «Knowledge of a common historical past is essential to maintaining a people’s signs of identity» 12 • Urazandi, a project shining light on Basque emigration 14 • Basque periodicals published in Venezuela and Mexico Issue 68. Year 2005 ARTICLES 16 • The Basque "Y", a train on the move 18 • Nestor Basterretxea, sculptor. AUTHOR A return traveller Eusko Jaurlaritza-Kanpo Harremanetarako Idazkaritza 20 • Euskaditik: The Bishop of Bilbao, elected Nagusia President of the Spanish Episcopal Conference Basque Government-General 21 • Euskaditik: Election results Secretariat for Foreign Action 22 • Euskal gazteak munduan / Basque youth C/ Navarra, 2 around the world 01007 VITORIA-GASTEIZ Nestor Basterretxea Telephone: 945 01 7900 [email protected] DIRECTOR EUSKAL ETXEAK / ETXEZ ETXE Josu Legarreta Bilbao COORDINATION AND EDITORIAL 24 • Proliferation of programs in the USA OFFICE 26 • Argentina. An exhibition for the memory A. Zugasti (Kazeta5 Komunikazioa) 27 • Impressions of Argentina -

Elko Jaietan 50 Urte Celebrating 50 Years of Basque Tradition

2013 Elko Jaietan 50 Urte Celebrating 50 Years of Basque Tradition 2013 Schedule of Events Elko Basque Festival Celebrating 50 Years Elko Jaietan 50 Urte Friday, July 5th 10:00 a.m. – Parade – Downtown Elko Ostirala 5an Uztaila Starting at the Crystal Theater on Commercial Street, continuing through Downtown Elko down Idaho Street, ending at the Elko County 6:00 p.m. – Kickoff/Txupinazua – Fronton Fairgrounds. come during the weekend. There will be dancing by the Elko Ariñak dancers, 1:00 p.m. – Games & Dancing – Elko County Fairgrounds Basque sport exhibition of weight lifting and wood chopping, and handball $10 Adults, $5 Children 12 & Under games. Stay for exceptional food, drink, bounce house and the North Featuring the following dance groups: Elko Ariñak, Utah’ko Triskalariak, American Basque Organizations Txerriki contest, a celebration of all things Reno Zazpiak Bat, Boise Oinkari, aGauden Bat from Chino, CA, Zazpiak- Bat from San Francisco, CA. Watch traditional Basque rural sports featuring weightlifting, wood chopping, weight carrying, bale toss, tug-o-war, and more! 9:00 p.m. – Dance – Eusko Etxea – Elko Basque Clubhouse Saturday, July 6th $12 Admission Laurnbata 6an Uztaila Dance - featuring Boise’s Amuma Says No; come 7:00 a.m. – 5K Run/Walk – Eusko Etxtea – Elko Basque Clubhouse of dancing, catching up $20 participation fee and you get a t-shirt with old friends and Registration is at 6:15 a.m. Race starts at 7:00 a.m. making new ones. For more information contact Cody Krenka at 738-6479. 8:00 a.m. – Golf Tournament – Ruby View Golf Course $30 per person a $120 per team DOES NOT INCLUDE GREENS FEES OR CART FEE Registration is at 7:00 a.m. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel.