Comparing the Basque Diaspora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Previous Studies

ABSTRACTS OF THE CONGRESS 1.- PREVIOUS STUDIES 1.1.- Multidisciplinary studies (historical, archaeological, etc.). 30 ANALYSIS AND PROPOSAL OF RENOVATION CRITERIA AT THE BUILDING HEADQUARTER OF THE PUBLIC WORKS REGIONAL MINISTER IN CASTELLÓN (GAY AND JIMÉNEZ, 1962) Martín Pachés, Alba; Serrano Lanzarote, Begoña; Fenollosa Forner, Ernesto ……...... 32 NEW CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE STUDY OF THE HERMITAGES SETTING AROUND CÁCERES Serrano Candela, Francisco ……...... 55 THE ORIENTATION OF THE ROMANESQUE CHURCHES OF VAL D’ARAN IN SPAIN (11TH-13TH CENTURIES) Josep Lluis i Ginovart; Mónica López Piquer ……...... 73 SANTO ANTÔNIO CONVENT IN IGARASSU, PE – REGISTER OF AN INTERVENTION Guzzo, Ana Maria Moraes; Nóbrega, Claudia ……...... 104 DONIBANE N134: HISTORICAL-CONSTRUCTIVE ANALYSIS OF LATE MEDIEVAL VILLAGE MANOR HOUSE IN PASAIA (GIPUZKOA - SPAIN) Luengas-Carreño, Daniel; Crespo de Antonio, Maite; Sánchez-Beitia, Santiago ……...... 126 CONSERVATION OF PREFABRICATED RESIDENTIAL HERITAGE OF THE CENTURY XX. JEAN PROUVÉ’S WORK Bueno-Pozo, Verónica; Ramos-Carranza, Amadeo ……...... 169 COMPARED ANALYSIS AS A CONSERVATION INSTRUMENT.THE CASE OF THE “MASSERIA DEL VETRANO” (ITALY) Pagliuca, Antonello; Trausi, Pier Pasquale ……...... 172 THE INTERRELATION BETWEEN ARCHITECTURAL CONCEPTION AND STRUCTURE OF THE DOM BOSCO SANCTUARY THROUGH THE RECOUPERATION OF ITS DESIGN Oliveira, Iberê P.; Brandão, Jéssica; Pantoja, João C.; Santoro, Aline M. C. ……...... 177 THE SILVER ROAD THROUGH COLONIAL CHRONICLES. TOOLS FOR THE ANALYSIS AND ENHANCEMENT OF HISTORIC LANDSCAPE Malvarez, María Florencia ……...... 202 ANTHROPIC TRANSFORMATIONS AND NATURAL DECAY IN URBAN HISTORIC AGGREGATES: ANALYSIS AND CRITERIA FOR CATANIA (ITALY) Alessandro Lo Faro; Angela Moschella; Angelo Salemi; Giulia Sanfilippo ……...... 216 THE BRICK BUILT FAÇADES OF TIERRA DE PINARES IN SEGOVIA. THE CASE OF PINARNEGRILLO Gustavo Arcones-Pascual; Santiago Bellido-Blanco; David Villanueva-Valentín-Gamazo; Alberto Arcones-Pascual ……..... -

Pais Vasco 2018

The País Vasco Maribel’s Guide to the Spanish Basque Country © Maribel’s Guides for the Sophisticated Traveler ™ August 2018 [email protected] Maribel’s Guides © Page !1 INDEX Planning Your Trip - Page 3 Navarra-Navarre - Page 77 Must Sees in the País Vasco - Page 6 • Dining in Navarra • Wine Touring in Navarra Lodging in the País Vasco - Page 7 The Urdaibai Biosphere Reserve - Page 84 Festivals in the País Vasco - Page 9 • Staying in the Urdaibai Visiting a Txakoli Vineyard - Page 12 • Festivals in the Urdaibai Basque Cider Country - Page 15 Gernika-Lomo - Page 93 San Sebastián-Donostia - Page 17 • Dining in Gernika • Exploring Donostia on your own • Excursions from Gernika • City Tours • The Eastern Coastal Drive • San Sebastián’s Beaches • Inland from Lekeitio • Cooking Schools and Classes • Your Western Coastal Excursion • Donostia’s Markets Bilbao - Page 108 • Sociedad Gastronómica • Sightseeing • Performing Arts • Pintxos Hopping • Doing The “Txikiteo” or “Poteo” • Dining In Bilbao • Dining in San Sebastián • Dining Outside Of Bilbao • Dining on Mondays in Donostia • Shopping Lodging in San Sebastián - Page 51 • Staying in Bilbao • On La Concha Beach • Staying outside Bilbao • Near La Concha Beach Excursions from Bilbao - Page 132 • In the Parte Vieja • A pretty drive inland to Elorrio & Axpe-Atxondo • In the heart of Donostia • Dining in the countryside • Near Zurriola Beach • To the beach • Near Ondarreta Beach • The Switzerland of the País Vasco • Renting an apartment in San Sebastián Vitoria-Gasteiz - Page 135 Coastal -

Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Center welcomes Gloria Totoricagüena New faculty member Gloria Totoricagüena started to really compare and analyze their FALL began working at the Center last spring, experiences, to look at the similarities and having recently completed her Ph.D. in differences between that Basque Center and 2002 Comparative Politics. Following is an inter- Basque communities in the U.S. So that view with Dr. Totoricagüena by editor Jill really started my academic interest. Al- Berner. though my Master’s degree was in Latin American politics and economic develop- NUMBER 66 JB: How did your interest in the Basque ment, the experience there gave me the idea diaspora originate and develop? GT: I really was born into it, I’ve lived it all my life. My parents are survivors of the In this issue: bombing of Gernika and were refugees to different parts of the Basque Country. And I’ve also lived the whole sheepherder family Gloria Totoricagüena 1 experience that is so common to Basque identity in the U.S. My father came to the Eskerrik asko! 3 U.S. as a sheepherder, and then later went Slavoj Zizek lecture 4 back to Gernika where he met my mother and they married and came here. My parents went Politics after 9/11 5 back and forth actually, and eventually settled Highlights in Boise. So this idea of transnational iden- 6 tity, and multiculturalism, is not new at all to Visiting scholars 7 me. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Dative (First) Complements in Basque

Dative (first) complements in Basque BEATRIZ FERNÁNDEZ JON ORTIZ DE URBINA Abstract This article examines dative complements of unergative verbs in Basque, i.e., dative arguments of morphologically “transitive” verbs, which, unlike ditransitives, do not co-occur with a canonical object complement. We will claim that such arguments fall under two different types, each of which involves a different type of non-structural licensing of the dative case. The presence of two different types of dative case in these constructions is correlated with the two different types of complement case alternations which many of these predicates exhibit, so that alternation patterns will provide us with clues to identify different sources for the dative marking. In particular, we will examine datives alternating with absolutives (i.e., with the regular object structural case in an ergative language) and datives alternating with postpositional phrases. We will first examine an approach to the former which relies on current proposals that identify a low applicative head as case licenser. Such approach, while accounting for the dative case, raises a number of issues with respect to the absolutive variant. As for datives alternating with postpositional phrases, we claim that they are lexically licensed by the lower verbal head V. Keywords Dative, conflation, lexical case, inherent case, case alternations 1. Preliminaries: bivalent unergatives Bivalent unergatives, i.e., unergatives with a dative complement, have remained largely ignored in traditional Basque studies, perhaps due to the Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 11-1 (2012), 83-98 ISSN 1645-4537 84 Beatriz Fernández & Jon Ortiz de Urbina identity of their morphological patterns of case marking and agreement with those of ditransitive configurations. -

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor A Thesis in the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada March 2019 © Kyle McCreanor, 2019 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Kyle McCreanor Entitled: Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _________________________________ Chair Dr. Andrew Ivaska _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Ted McCormick _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Cameron Watson _________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Gavin Foster Approved by _________________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______________ 2019 _________________________________________ Dean of Faculty iii Abstract Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor This thesis examines the relationships between Irish and Basque nationalists and nationalisms from 1895 to 1939—a period of rapid, drastic change in both contexts. In the Basque Country, 1895 marked the birth of the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (Basque Nationalist Party), concurrent with the development of the cultural nationalist movement known as the ‘Gaelic revival’ in pre-revolutionary Ireland. In 1939, the Spanish Civil War ended with the destruction of the Spanish Second Republic, plunging Basque nationalism into decades of intense persecution. Conversely, at this same time, Irish nationalist aspirations were realized to an unprecedented degree during the ‘republicanization’ of the Irish Free State under Irish leader Éamon de Valera. -

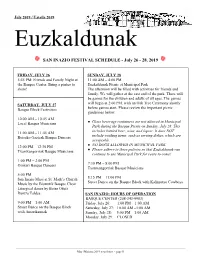

SAN INAZIO FESTIVAL SCHEDULE - July 26 - 28, 2019

1 July 2019 / Uztaila 2019 Euzkaldunak SAN INAZIO FESTIVAL SCHEDULE - July 26 - 28, 2019 FRIDAY, JULY 26 SUNDAY, JULY 28 5:45 PM: Friends and Family Night at 11:00 AM – 4:00 PM the Basque Center. Bring a pintxo to Euzkaldunak Picnic at Municipal Park share! The afternoon will be filled with activities for friends and family. We will gather at the east end of the park. There will be games for the children and adults of all ages. The games SATURDAY, JULY 27 will begin at 2:00 PM, with an Oak Tree Ceremony shortly Basque Block Festivities before games start. Please review the important picnic guidelines below: 10:00 AM – 10:45 AM ● Local Basque Musicians Glass beverage containers are not allowed in Municipal Park during the Basque Picnic on Sunday, July 28. This 11:00 AM – 11:45 AM includes bottled beer, wine, and liquor. It does NOT Boiseko Gazteak Basque Dancers include cooking items, such as serving dishes, which are acceptable. ● 12:00 PM – 12:30 PM NO DOGS ALLOWED IN MUNICIPAL PARK ● Txantxangorriak Basque Musicians Please adhere to these policies so that Euzkaldunak can continue to use Municipal Park for years to come! 1:00 PM – 2:00 PM Oinkari Basque Dancers 7:30 PM – 8:00 PM Txantxangorriak Basque Musicians 5:00 PM San Inazio Mass at St. Mark’s Church 8:15 PM – 11:00 PM Music by the Biotzetik Basque Choir Street Dance on the Basque Block with Kalimotxo Cowboys Liturgical dance by Boise Oñati Dantza Taldea SAN INAZIO: HOURS OF OPERATION BASQUE CENTER (208-343-9983) 9:00 PM – 1:00 AM Friday, July 26: 1:00 PM – 1:00 AM Street Dance on the Basque Block Saturday, July 27: 10:00 AM –1:00 AM with Amerikanuak Sunday, July 28: 5:00 PM – 1:00 AM Monday, July 29: CLOSED May /Maiatza 2019 newsletter - page 1 2 FRIENDS AND FAMILY NIGHT – JULY 26 Please join us as we kick off another great San Inazio Basque Festival Friday, July 26, at 5:45 PM. -

The Basque Experience with the Irish Model

WORKING PAPERS IN CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND SOCIAL JUSTICE ISSN 2053-0129 (Online) From Belfast to Bilbao: The Basque Experience with the Irish Model Eileen Paquette Jack, PhD Candidate School of Politics, International Studies and Philosophy, Queen’s University, Belfast [email protected] Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice CTSJ WP 06-15 April 2015 Page | 1 Abstract This paper examines the izquierda Abertzale (Basque Nationalist Left) experience of the Irish model. Drawing upon conflict transformation scholars, the paper works to determine if the Irish model serves as a tool of conflict transformation. Using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), the paper argues that it is a tool, and focuses on the specific finding that it is one of many learning tools in the international sphere. It suggests that this theme can be generalized and could be found in other case studies. The paper is located within the discipline of peace and conflict studies, but uses a method from psychology. Keywords: Conflict transformation, Basque Country, Irish model, Peace Studies Introduction1 The conflict in the Basque Country remains one of the most intractable conflicts, and until recently was the only conflict within European borders. Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) has waged an open, violent conflict against the Spanish state, with periodic ceasefires and attempts for peace. Despite key differences in contexts, the izquierda Abertzale (‘nationalist left’) has viewed the Irish model – defined in this paper as a process of transformation which encompasses both the Good Friday Agreement (from here on referred to as GFA) and wider peace process in Northern Ireland – with potential. -

Process of Palatalization That Must Be Stated As Two Related

Palatalization in Biscayan Basque and Feature Geometry Item Type Article Authors Hualde, Jose Publisher Department of Linguistics, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Download date 24/09/2021 16:22:26 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/227251 Palatalization in Biscayan Basque and Feature Geometry José Ignacio Hualde University of Southern California 1.Introduction Archangeli (1987) has pointed out thatthe hierarchical model offeaturerepresentationcombinedwiththestatementof phonological rules in terms of conditions and parameters offers the advantage thatit allows the expression as a single rule of unitary processes that must be stated as multiple operations within other frameworks. In this paper Iwill offer an example of this (cf. Hualde, 1987 for another example).Iwill show that a seemingly complex process of palatalization that must be stated as two related but different operations within a linear model, can be straightforwardly captured in the hierarchical /parametrical approach by taking into account the geometrical structures on which the palatalization rule applies; in particular, the branching structures created by a rule of place assimilation. Iwill assume that assimilatory processes have the effect of creating complex structures where features or nodes are shared by several segments. From this assumption we canmake 36 predictions about how other rules may apply to the output of a process ofassimilation. These predictions are very differentin some cases from what one would expect from aformulation of the rulesin a linear, feature -changing framework. In the case to be examined here, the predictions made by taking into account derived geometrical structures receive very strong confirmation. I will consider a rule of palatalizationin two Basque dialects. -

Sentence Negation in Basque

".' ; Sentence negation in Basque ITZIAR LAKA (M.I.T.) This paper presents an analysis of sentence negation in Basque!. Basque negative sentences show a differentpattern from non-negative ones with respect to the placement of the inflected verb. This particular pattern displays an interesting asymmetry depending on the clause type. The phenomena are explained in terms of head movement. The negative particle ez 'not' is analyzed as a head, in the spirit of Pollock (1989). This head takes IP as its complement and projects a Neg Phrase. At S-struc ture, INFL adjoins to negation; the fact that negation is initial unlike the rest of the heads in Basque creates the 'dislocated' pattern of matrix sentence negation. In embedded clauses, the complex [NEGATION/INFL] adjoins to CaMP, which is final. This latter movement is the source of the asymmetry between matrix and embedded sentence negation. The paper also explores grammatical constraints on sentence negation in natural languages. It is argued that Negative Polarity ltems(NPI) are licensed by negation under c-command at S-structure, and that sentence negation must be c-commanded by Tense also at S-structure. The first condition is shown to account for NPI licensing by negation in Basque and English. The second condition which is named the Tense C-command Condition (TCC) is proposed based mainly on evidence from Basque. Some cross-lin guistic evidence is shown to support the hypothesis as universal. The paper is organized as follows: The first section presents some general properties of Basque grammar relevant for the analysis. The second section describes the phenomena induced by negation both in matrix and embedded clauses. -

Iglesia De San Martín (Arrieta)

PATRIMONIO HISTÓRICO DE BIZKAIA Iglesia de San Martín (Arrieta) Edificio Mobiliario Descripción El Retablo Mayor ocupa la testera del presbiterio y es una sencilla estructura en casillero, de madera repintada, que se Presidiendo la plaza de la anteiglesia se levanta el templo organiza en cinco calles, banco y dos pisos más cimal escalonado parroquial de Arrieta, un edificio planteado en una larga nave, recercado por guardapolvo. Definen las calles y casas pilaretes distribuida en cinco tramos marcados por columnas toscanas góticos y frisillos lisos, pero en el bancal hay columnas que adosadas a pilas, lo que crea unas reducidas pero funcionales llevan decoración de grutescos. capillas altas a los flancos. Sobre las columnas cargan los arcos generatrices de la bóveda, que es baída y de albañilería. Una Es un retablo viñeta que recoge mucha información capilla mayor, más estrecha y cuadrada, remata la nave. Su historiada; así, en el banco hay tallas de un apostolado bóveda es del mismo tipo, si bien al centro se perfora una incompleto, y en las casas, relieves narrativos de la vida de San pequeña media naranja para tragaluz. La capilla que se abre Martín de Tours, titular, cuyo bulto aparece en el centro. a la izquierda, en el segundo tramo, es un añadido moderno. También es de bulto el Calvario. Aparte de lo descrito, existe un pórtico que afecta al flanco Relieves y tallas son del mismo estilo que la mazonería, de mediodía y a los pies. Tiene mucho protagonismo, incluso hispanoflamencos de hacia el año 1520. Aparte del repintado urbanístico, en la parte orientada a la plaza. -

Dative Overmarking in Basque: Evidence of Spanish-Basque Convergence

Dative Overmarking in Basque: Evidence of Spanish-Basque Convergence Jennifer Austin University of New Jersey, Rutgers. [email protected] Abstract This paper investigates a recent change in the grammar of spoken Basque which results in the substitution of dative case and agreement for absolutive case and agreement in marking animate, specific direct objects. I argue that this pattern of use is due to convergence between the feature matrix of the functional category AGR in Spanish and Basque. In contrast to previous studies which point to interface areas as the locus of syntactic convergence, I argue that this is a change affecting the core grammar of Basque. Furthermore, I suggest that the appearance of this case marking pattern in spoken Basque is probably attributable to recent changes in the demographics of Basque speakers and that its use is related to the degree of proficiency in each language of adult bilingual speakers. Laburpena Lan honetan euskara mintzatuaren gramatikan gertatu berri den aldaketa bat ikertzen da, hain zuzen ere, kasu datiboa eta aditz komunztaduraren ordezkapena kasu absolutiboa eta aditz komunztaduraren ordez objektu zuzenak --animatuak eta zehatzak—markatzen direnean. Nire iritziz, erabilera hori gazteleraz eta euskaraz dagoen AGR delako kategori funtzionalaren ezaugarri taulen bateratzeari zor zaio. Aurreko ikerketa batzuetan hizkuntza arteko ukipen eremuak bateratze sintaktikoaren gunetzat jotzen badira ere, nire iritziz aldaketa horrek euskararen gramatika oinarrizkoari eragiten dio. Areago, esango nuke kasu marka erabilera hori, ziurrenik, euskal hiztunen artean gertatu berri diren aldaketa demografikoen ondorioz agertzen dela euskara mintzatuan eta hiztun elebidun helduek hizkuntza bakoitzean daukaten gaitasun mailari lotuta dagoela. Keywods: Bilingualism, syntactic convergence, language contact.