Legal Review of the Jordanian Decentralization Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annex C3: Draft Esa and Record of Public Consultation

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT DISI-MUDAWARRA TO AMMAN WATER CONVEYANCE SYSTEM PART C: PROJECT-SPECIFIC ESA ANNEX C3: DRAFT ESA AND RECORD OF PUBLIC CONSULTATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS i LIST OF APPENDICES i 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 SECOND PHASE CONSULTATION METHODOLOGY 1 3 RESULTS OF SECOND PHASE CONSULTATION 3 3.1 Issues Identified at Abu Alanda 3 3.2 Issues Identified at Amman 3 3.3 Issues Identified at Aqaba Session 4 4 QUESTIONS AND COMMENTS AT THE SECOND PHASE CONSULTATION SESSIONS 6 4.1 Questions and Comments at the Abu Alanda Consultation Session 6 4.2 Questions and Comments at Amman Consultation Session 8 4.3 Questions and Comments at Aqaba Consultation Session 13 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix 1: Environmental Scoping Session − Invitation Letters and Scoping Session Agenda − Summary of the Environmental and Social Assessment Study − Handouts Distributed at the Second Phase Consultation Sessions − List of Invitees − List of Attendees Final Report Annex C3-i Consolidated Consultants ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT DISI-MUDAWARRA TO AMMAN WATER CONVEYANCE SYSTEM PART C: PROJECT-SPECIFIC ESA 1 INTRODUCTION The construction of the Disi-Mudawarra water conveyance system will affect all of the current and future population in the project area and to a certain extent the natural and the built up environment as well as the status of water resources in Jordan. Towards the end of the environmental and social assessment study of this project, three public consultation sessions on the findings of the draft ESA (second phase consultation) were implemented in the areas of Abu- Alanda, Amman and Aqaba. -

Amman, Jordan

MINISTRY OF WATER AND IRRIGATION WATER YEAR BOOK “Our Water situation forms a strategic challenge that cannot be ignored.” His Majesty Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein “I assure you that the young people of my generation do not lack the will to take action. On the contrary, they are the most aware of the challenges facing their homelands.” His Royal Highness Hussein bin Abdullah Imprint Water Yearbook Hydrological year 2016-2017 Amman, June 2018 Publisher Ministry of Water and Irrigation Water Authority of Jordan P.O. Box 2412-5012 Laboratories & Quality Affairs Amman 1118 Jordan P.O. Box 2412 T: +962 6 5652265 / +962 6 5652267 Amman 11183 Jordan F: +962 6 5652287 T: +962 6 5864361/2 I: www.mwi.gov.jo F: +962 6 5825275 I: www.waj.gov.jo Photos © Water Authority of Jordan – Labs & Quality Affairs © Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources Authors Thair Almomani, Safa’a Al Shraydeh, Hilda Shakhatreh, Razan Alroud, Ali Brezat, Adel Obayat, Ala’a Atyeh, Mohammad Almasri, Amani Alta’ani, Hiyam Sa’aydeh, Rania Shaaban, Refaat Bani Khalaf, Lama Saleh, Feda Massadeh, Samah Al-Salhi, Rebecca Bahls, Mohammed Alhyari, Mathias Toll, Klaus Holzner The Water Yearbook is available online through the web portal of the Ministry of Water and Irrigation. http://www.mwi.gov.jo Imprint This publication was developed within the German – Jordanian technical cooperation project “Groundwater Resources Management” funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) Implemented by: Foreword It is highly evident and well known that water resources in Jordan are very scarce. -

Annual Progress Report Period 12Th – July 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021

USAID JORDAN WATER INFRASTRUCTURE Annual Progress Report Period 12th – July 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021 Submission Date: Draft July 1, 2021, Final July 15, 2021 USAID Contract Number: AID-OAA-I-15-00047, Order: 72027818F00002 Contract/Agreement Period: July 16, 2018 to September 30, 2022 COR Name: Akram AlQhaiwi Submitted by: Rick Minkwitz, Chief of Party CDM International Inc. 73 Al Mutanabi St, Amman, Jordan Tel: 009626 4642720 Email: [email protected] This document was produced for review and approval by the United States Agency for International Development / Jordan (USAID/Jordan). July 2008 1 CONTENTS Contents .................................................................................................................... 3 Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................ 5 1. Background ...................................................................................................... 8 a. Introduction ......................................................................... 8 b. Report Period ...................................................................... 8 2. Activity Overview .......................................................................................... 8 a. Activity Details ................................................................... 8 b. Executive Summary ............................................................ 10 3. Activity Implementation .............................................................................. 16 a. Progress -

Jordan's Decentralisation Reform

OECD Open Government Review Jordan Towards a New Partnership with Citizens: Jordan’s Decentralisation Reform HIGHLIGHTS 2017 PRELIMINARY VERSION Brochure design by baselinearts.co.uk by design Brochure OECD OPEN GOVERNMENT REVIEW – JORDAN HIGHLIGHTS King Abdullah II speaks during the opening of the first ordinary session of 18th Parliament in Amman, November 7, 2016. WHAT DOES THE OECD STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT The OECD defines Open Government as “a culture of ANALYSE? governance based on innovative and sustainable policies and practices inspired by the principles of transparency, accountability, In the context of its efforts to bring policies and public services and participation that fosters democracy and inclusive growth” closer to citizens, the Government of Jordan asked the OECD Open Government policies are a means to improve to provide an analysis of the ongoing decentralisation reform the quality of a country’s democratic life in order to from the perspective of the principles and practices of open better meet the needs of its people. They yield a great government. In addition to providing analysis of the context, variety of benefits to businesses and citizens as well as to the policy areas covered in the OECD assessment include: implementing governments. l Improving centre-of-government (CoG) capacity to steer Key examples include: and lead decentralisation reform and its implementation. l Increasing trust in government l Strengthening analytical and evaluation capacity for l Ensuring better policy outcomes better policy-making and service delivery. l Enhancing policy efficiency and effectiveness l Enhancing transparency, accountability and citizen l Strengthening policy and regulatory compliance participation through a more open government approach l Promoting inclusive socio-economic development across all levels of Jordan’s public administration. -

Disaster Risk Reduction Assessment Understanding Livelihood Resilience in Jordan

Jordan Cover photo: Arabah, Jordan Rift Valley © Michael Privorotsky, 2009 DISASTER RISK REDUCTION ASSESSMENT UNDERSTANDING LIVELIHOOD RESILIENCE IN JORDAN ASSESSMENT REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 Contents Executive Summary 3 List Of Acronyms 7 Geographical Classifications 8 Introduction: Context And Objectives 9 Methodology 12 Findings 17 Socio-Economic Challenges And Risks 19 Environmental Challenges And Risks 26 Livelihood Resilience: Trends Over Time 32 Challenges Faced In Risk Mitigation And Preparedness 32 Summary 34 Conclusion And Recommendations 36 Annex 1: Focus Group Discussion Question Route 40 Annex 2: Elevation, Landcover, Sloping Maps Used For Zoning Exercise 45 Annex 3: Livelihood Zones In Jordan (Participatory Mapping Exercise) 48 Annex 4: Risk Perceptions Across Jordan 49 2 Executive Summary Context According to the INFORM 2016 risk index,1 which assesses global risk levels based on hazard exposure, fragility of socio- economic systems and insufficient institutional coping capacities, Jordan has a medium risk profile, with increasing socio-economic vulnerability being a particular area of concern.2 Since 1990, Jordan has also experienced human and economic losses due to flash floods, snowstorms, cold waves, and rain which is indicative of the country’s vulnerability to physical hazards.3 Such risk factors are exacerbated by the fact that Jordan is highly resource-constrained; not only is it semi-arid with only 2.6% of arable land,4 but it has also been ranked as the third most water insecure country in the world.5 Resource scarcity aggravates vulnerabilities within the agriculture sector which could have severe implications given that agriculture provides an important means of livelihood for 15% of the country’s population, primarily in rural areas.6 Resilience of agriculture is also closely linked to food and nutrition security. -

USAID Health Service Delivery Quarterly Progress Report

USAID Health Service Delivery Quarterly Progress Report January 1, 2020 to March 31, 2020 Submission Date: April 30, 2020 Agreement Number: AID-278-A-16-00002 Agreement Period: March 15, 2016 to March 14, 2021 Agreement Officer’s Representative: Dr. Nagham Abu Shaqra Submitted by: Dr. Sabry Hamza, Chief of Party Abt Associates 6130 Executive Blvd. Rockville, MD 20852, USA Tel: +1-301-913-0500/Mobile: +962-79-668-4533 Email: [email protected] This document was produced for review and approval by the United States Agency for International Development/Jordan (USAID/Jordan). 1 USAID Health Service Delivery FY 20 Q2 Progress Report Submitted to USAID on April 30, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................. III GLOSSARY ...................................................................................................................... VI 1. ACTIVITY OVERVIEW ................................................................................................. 1 A. ACTIVITY DETAILS .......................................................................................................................... 1 B. VISION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 C. MISSION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 D. IMPLEMENTATION APPROACH ...................................................................................................... -

Subnational Governance in Jordan

THE INSTITUTE FOR MIDDLE EAST STUDIES IMES CAPSTONE PAPER SERIES CENTRALIZED DECENTRALIZATION: SUBNATIONAL GOVERNANCE IN JORDAN GRACE ELLIOTT MATT CIESIELSKI REBECCA BIRKHOLZ MAY 2018 THE INSTITUTE FOR MIDDLE EAST STUDIES THE ELLIOTT SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY © OF GRACE ELLIOTT, MATT CIESIELSKI, REBECCA BIRKHOLZ, 2018 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Literature Review: Decentralization and 3 Authoritarian Upgrading Methodology 7 Local Governance in Jordan 9 Political Economy and Reform 12 Decentralization in Jordan 15 Decentralization as a Development Initiative 20 Political Rhetoric 28 Opportunities and Challenges 31 Conclusion 35 Works Cited 37 Appendix 41 1 Introduction Jordan is one of the last bastions of stability in an otherwise volatile region. However, its stability is threatened by a continuing economic crisis. In a survey conducted across all twelve governorates in 2017, only 22% of citizens view Jordan’s overall economic condition as “good” or “very good” compared to 49% two years ago.1 Against this backdrop of economic frustration, Jordan is embarking on a decentralization process at the local level in an attempt to bring decision-making closer to the citizen. In 2015, Jordan passed its first Decentralization Law, which continued calls from King Abdullah II dating back to 2005 to “enhance our democratic march and to continue the process of political, economic, social and administrative reform” by encouraging local participation in the provision of services and investment priorities.2 This is the latest in a series of small steps taken by the central government intended to improve governance at the local level and secure long-term stability in the Kingdom. -

Women's Political Participation in Jordan

MENA - OECD Governance Programme WOMEN’S Political Participation in JORDAN © OECD 2018 | Women’s Political Participation in Jordan | Page 2 WOMEN’S POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN JORDAN: BARRIERS, OPPORTUNITIES AND GENDER SENSITIVITY OF SELECT POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS MENA - OECD Governance Programme © OECD 2018 | Women’s Political Participation in Jordan | Page 3 OECD The mission of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is to promote policies that will improve the economic and social well-being of people around the world. It is an international organization made up of 37 member countries, headquartered in Paris. The OECD provides a forum in which governments can work together to share experiences and seek solutions to common problems within regular policy dialogue and through 250+ specialized committees, working groups and expert forums. The OECD collaborates with governments to understand what drives economic, social and environmental change and sets international standards on a wide range of things, from corruption to environment to gender equality. Drawing on facts and real-life experience, the OECD recommend policies designed to improve the quality of people’s. MENA - OECD MENA-OCED Governance Programme The MENA-OECD Governance Programme is a strategic partnership between MENA and OECD countries to share knowledge and expertise, with a view of disseminating standards and principles of good governance that support the ongoing process of reform in the MENA region. The Programme strengthens collaboration with the most relevant multilateral initiatives currently underway in the region. In particular, the Programme supports the implementation of the G7 Deauville Partnership and assists governments in meeting the eligibility criteria to become a member of the Open Government Partnership. -

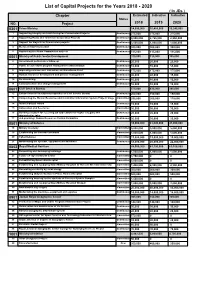

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2018 2019 2020 0301 Prime Ministry 14,090,000 10,455,000 10,240,000 1 Supporting Integrity and Anti-Corruption Commission Projects Continuous 275,000 275,000 275,000 2 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 9,900,000 8,765,000 8,550,000 3 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 4 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 5 Supporting the Media Commission projects Continuous 115,000 115,000 115,000 0501 Ministry of Public Sector Development 310,000 310,000 305,000 6 Government performance follow up Continuous 20,000 20,000 20,000 7 Public sector reform program management administration Continuous 55,000 55,000 55,000 8 Improving services and Innovation and Excellence Fund Continuous 175,000 175,000 175,000 9 Human resources development and policies management Continuous 40,000 40,000 35,000 10 Re-structuring Continuous 10,000 10,000 10,000 11 Communication and change management Continuous 10,000 10,000 10,000 0601 Civil Service Bureau 575,000 435,000 345,000 12 Enhancement of institutional capacities of Civil Service Bureau Continuous 200,000 150,000 150,000 13 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Project/ Stage Committed 290,000 200,000 110,000 2 14 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 15 Automation and E-services Committed 30,000 30,000 30,000 16 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 20,000 20,000 20,000 administrative jobs. -

JICA's Cooperation for Water Sector in Jordan

JICA’s Cooperation for Water Sector in Jordan 30 years history of remarkable achievements 1 | P a g e Message from Chief Representative of JICA Jordan Mr. TANAKA Toshiaki Japanese ODA to Jordan started much earlier than the establishment of JICA office. The first ODA loan to Jordan was provided in 1974, the same year when Embassy of Japan in Jordan was established. The first technical cooperation project started in 1977, though technical cooperation to Jordan may have started earlier, and the first grant aid to Jordan was provided in 1979. Since then, the Government of Japan has provided Jordan with total amount of more than 200 billion Japanese yen as ODA loan, more than 60 billion yen as Grant aid and nearly 30 billion yen as technical cooperation. In 1985, two agreements between the two countries on JICA activities were concluded. One is the technical cooperation agreement and the other is the agreement on Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers. On the basis of the agreement, JICA started JOCV program in Jordan and established JOCV coordination office which was followed by the establishment of JICA Jordan office. For the promotion of South-South Cooperation in the region, Japan-Jordan Partnership Program was agreed in 2004, furthering Jordan’s position as a donor country and entering a new stage of relationship between the two countries. In 2006, Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) inaugurated Amman office, which was integrated with JICA Jordan office in 2008 when new JICA was established as a result of a merger of JICA with ODA loan operation of JBIC. -

THE STARTUP GUIDE Business in Jordan

Your complete guide to registering and licensing a small THE STARTUP GUIDE business in Jordan Find out what to do, where to go and what fees are required to formalize your small business in this simple, step-by-step guide Contents WHY SHOULD I REGISTER AND LICENSE MY BUSINESS? ........................................................................................ 2 WHAT ARE THE STEPS I NEED TO TAKE IN ORDER TO FORMALIZE MY BUSINESS? ............................................... 3 HOW DO I KNOW WHAT TYPE OF BUSINESS TO REGISTER? ................................................................................. 4 HOW DO I CHOOSE A BUSINESS STRUCTURE THAT’S RIGHT FOR ME? ................................................................. 6 I’VE CHOSEN MY BUSINESS STRUCTURE… WHAT NEXT? ...................................................................................... 8 I’VE GOTTEN MY PRE-APPROVALS. HOW DO I REGISTER MY BUSINESS? ............................................................. 9 A) REGISTERING AN INDIVIDUAL ESTABLISHMENT ........................................................................................ 10 B) REGISTERING A GENERAL PARTNERSHIP OR LIMITED PARTNERSHIP COMPANY ...................................... 13 C) REGISTERING A LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY ........................................................................................... 16 D) REGISTERING A PRIVATE SHAREHOLDING COMPANY................................................................................ 20 I’VE REGISTERED MY BUSINESS. HOW CAN I SET -

Development Report 2015

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. JORDAN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2015 REGIONAL DISPARITIES JORDAN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2015 Regional Disparities Jordan Human Development Report 2015: Regional Disparities Project Board Members Mukhallad Omari, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation Zena Ali Ahmad, UNDP-Jordan Mohammad Nabulsi, Economic and Social Council National Reviewers Mukhallad Omari, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation Basem Kanan, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation Diya Elfadel, UNDP-Jordan Zein Soufan, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation Orouba Al-Sabbagh, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation Raedah Frehat, Jordanian National Commission for Women Junnara Murad, Development and Employment Fund Ahmad Al-Qubelat, Department of Statistics Maisoon Amarneh, Jordan Economic and Social Council Osama Al-Salaheen, Ministry of Social Development Reem Al-Zaben, Jordanian Hashemite Fund for Human Development Ali Al-Metleq, The Higher Population Council Laith Al-Qasem Abdelbaset Al-Thamnah, Department of Statistics JORDAN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2015 1 Jordan Human Development Report 2015: Regional Disparities International reviewers Selim Jahan, Director, Human Development Report Ofce Jon Hall, Policy Specialist, National Human Development Reports, UNDP Consultants Core Team of Writers Khalid W. Al-Wazani- Chief Researcher and Team Leader (Issnaad Consulting) Ahmad AL-Shoqran, Report Coordinator (Issnaad Consulting) Ibrahim Aljazy Alaa Bashaireh Other Participating Experts Fawaz Al-Momani Abdallah Ababneh Abdelbaset Al-Thamnah Fairouz Aldahmour Mohammad Bani Salameh Naser Abu Zayton Hani Kurdi Mohammad Nassrat Salma Nims Survey Team Naser Abu Zayton Taqwah Saleh Ebtisam Abdullah Issnaad Consulting Management advisory services Ahmad Hindawi Lara Khozouz Lana Mattar Taqwah Saleh 2 JORDAN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2015 Jordan Human Development Report 2015: Regional Disparities Jordan Human Development Report 2015: Regional Disparities No.