Subnational Governance in Jordan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time Needed to Assess Environmental Impact of Water Shortage. Case Study: Jerash Governorate / Jordan

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 10, Issue 7 Ver. III (July 2016), PP 58-63 www.iosrjournals.org Time needed to assess environmental impact of water shortage. case study: Jerash governorate / Jordan . Eham S. Al-Ajlouni Public Health Department, Health Sciences College, Saudi Electronic University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Abstract:Time needed to measure environmental impact varies according to the field (economic, financial, health, education, social, ..) and to the subject (project, policy, disease, program, ..) . The aim of this work was determining time duration needed to assess environmental impact of water shortage. Water share in Jerash governorate is only 71 litres per day per person, which is very low. So, cluster survey was applied, official records during 2000 – 2011 were reviewed and drinking water samples were analyzed. Water analysis data showed slight or no impact on ammonia, fluoride, and lead levels in water; and on pH and salinity of water; but there was high level of nitrate in water. Furthermore, national reports showed increased level of salinity of soil, however data of Total Dissolved Solids and pH of soil were officially not available. It was concluded that to show the negative impacts of water shortage on water quality and soil, time duration should be beyond 20 years. Moreover, salinity of soil could be indirectly affected by water shortage through over pumping and pollution, but mainly affected by agricultural practices and climate. Keywords:Environmental impact assessment; Falkenmark indicator; Jerash governorate; Time duration ;Water shortage. I. Introduction Duration of time frame to show positive or negative effects of a treatment, a project, a program, or a policy, is varied. -

Jordan Parliamentary Elections, 20 September

European Union Election Observation Mission The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Parliamentary Election 20 September 2016 Final Report European Union Election Observation Mission The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Parliamentary Election 20 September 2016 Final Report European Union Election Observation Mission The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Parliamentary Election, 20 September 2016 Final Report, 13 November 2016 THE HASHEMITE KINGDOM OF JORDAN Parliamentary Election, 20 September 2016 EUROPEAN UNION ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Page 1 Key Abbreviations Page 3 1. Executive Summary Page 4 2. Introduction and Acknowledgements Page 7 3. Political Context Page 8 4. Legal Framework Page 10 4.1 Applicability of International Human Rights Law 4.2 Constitution 4.3 Electoral Legislation 4.4 Right to Vote 4.5 Right to Stand 4.6 Right to Appeal 4.7 Electoral Districts 4.8 Electoral System 5. Election Administration Page 22 5.1 Election Administration Bodies 5.2 Voter Registration 5.3 Candidate Registration 5.4 Voter Education and Information 5.5 Institutional Communication 6 Campaign Page 28 6.1 Campaign 6.2 Campaign Funding 7. Media Page 30 7.1 Media Landscape 7.2 Freedom of the Media 7.3 Legal Framework 7.4 Media Violations 7.5 Coverage of the Election 8. Electoral Offences, Disputes and Appeals Page 35 9. Participation of Women, Minorities and Persons with Disabilities Page 38 __________________________________________________________________________________________ While this Final Report is translated in Arabic, the English version remains the only original Page 1 of 131 European Union Election Observation Mission The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Parliamentary Election, 20 September 2016 Final Report, 13 November 2016 9.1 Participation of Women 9.2 Participation of Minorities 9.3 Participation of Persons with Disabilities 10. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 His Majesty King Abdullah II

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 His Majesty King Abdullah II His Royal Highness Crown Prince of Jordan 6 | Tanmeyah Annual Report 2017 Tanmeyah Annual Report 2017 | 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from the Chairman ........................................................................................................................................ 8 About Tanmeyah – Jordan Microfinance Network .......................................................................................................... 9 Tanmeyah`s Vision, Mission ....................................................................................................................................... 10 Tanmeyah`s Board Members ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Tanmeyah’s Executive Team ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Tanmeyah`s Members ................................................................................................................................................ 13 Members’ Profile ........................................................................................................................................................ 13 Tanmeyah`s Partners ................................................................................................................................................. 16 Tanmeyah’s, Regional, and International Partnerships ................................................................................................ -

Gender Portrayal in the Jordanian Media Content

Gender Portrayal in the Jordanian Media Content An assessment study that aims to fostering gender balance in the media content Analysis of news and current affairs based on UNESCO’s Gender-Sensitive Indicators for Media Supported by findings of a round-table for editors and managers of media organizations, media experts and policy-makers June 2018 1 The designations employed and presentation of material throughout this study do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this study are those of the researchers; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Dates of research: December 2017 – March 2018 Research team: Senior researcher: Sawsan Zaideh Research assistants: Hadil Al-Biss, Mohammad Omar, Dana Al-Sheikh Illustrations and design: Maya Amer Acknowledgement: The assessment study has been produced by 7iber in close collaboration with UNESCO Amman Office and with the support of the International Programme for the Development of Communication (IPDC). The IPDC is the only multilateral forum in the UN system designed to mobilize the international community to discuss and promote media development in developing countries. The Programme not only provides support for media projects but also seeks an accord to secure a healthy environment for the growth of free and pluralistic media in developing countries. Please send comments to the email: [email protected] 2 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 4 2. -

Jordan's Decentralisation Reform

OECD Open Government Review Jordan Towards a New Partnership with Citizens: Jordan’s Decentralisation Reform HIGHLIGHTS 2017 PRELIMINARY VERSION Brochure design by baselinearts.co.uk by design Brochure OECD OPEN GOVERNMENT REVIEW – JORDAN HIGHLIGHTS King Abdullah II speaks during the opening of the first ordinary session of 18th Parliament in Amman, November 7, 2016. WHAT DOES THE OECD STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT The OECD defines Open Government as “a culture of ANALYSE? governance based on innovative and sustainable policies and practices inspired by the principles of transparency, accountability, In the context of its efforts to bring policies and public services and participation that fosters democracy and inclusive growth” closer to citizens, the Government of Jordan asked the OECD Open Government policies are a means to improve to provide an analysis of the ongoing decentralisation reform the quality of a country’s democratic life in order to from the perspective of the principles and practices of open better meet the needs of its people. They yield a great government. In addition to providing analysis of the context, variety of benefits to businesses and citizens as well as to the policy areas covered in the OECD assessment include: implementing governments. l Improving centre-of-government (CoG) capacity to steer Key examples include: and lead decentralisation reform and its implementation. l Increasing trust in government l Strengthening analytical and evaluation capacity for l Ensuring better policy outcomes better policy-making and service delivery. l Enhancing policy efficiency and effectiveness l Enhancing transparency, accountability and citizen l Strengthening policy and regulatory compliance participation through a more open government approach l Promoting inclusive socio-economic development across all levels of Jordan’s public administration. -

Disaster Risk Reduction Assessment Understanding Livelihood Resilience in Jordan

Jordan Cover photo: Arabah, Jordan Rift Valley © Michael Privorotsky, 2009 DISASTER RISK REDUCTION ASSESSMENT UNDERSTANDING LIVELIHOOD RESILIENCE IN JORDAN ASSESSMENT REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 Contents Executive Summary 3 List Of Acronyms 7 Geographical Classifications 8 Introduction: Context And Objectives 9 Methodology 12 Findings 17 Socio-Economic Challenges And Risks 19 Environmental Challenges And Risks 26 Livelihood Resilience: Trends Over Time 32 Challenges Faced In Risk Mitigation And Preparedness 32 Summary 34 Conclusion And Recommendations 36 Annex 1: Focus Group Discussion Question Route 40 Annex 2: Elevation, Landcover, Sloping Maps Used For Zoning Exercise 45 Annex 3: Livelihood Zones In Jordan (Participatory Mapping Exercise) 48 Annex 4: Risk Perceptions Across Jordan 49 2 Executive Summary Context According to the INFORM 2016 risk index,1 which assesses global risk levels based on hazard exposure, fragility of socio- economic systems and insufficient institutional coping capacities, Jordan has a medium risk profile, with increasing socio-economic vulnerability being a particular area of concern.2 Since 1990, Jordan has also experienced human and economic losses due to flash floods, snowstorms, cold waves, and rain which is indicative of the country’s vulnerability to physical hazards.3 Such risk factors are exacerbated by the fact that Jordan is highly resource-constrained; not only is it semi-arid with only 2.6% of arable land,4 but it has also been ranked as the third most water insecure country in the world.5 Resource scarcity aggravates vulnerabilities within the agriculture sector which could have severe implications given that agriculture provides an important means of livelihood for 15% of the country’s population, primarily in rural areas.6 Resilience of agriculture is also closely linked to food and nutrition security. -

Jordan Contents Executive Summary

FEBRUARY 24, 2020 LAND USE MEASURES TO SUSTAIN TRADITIONAL USES OF THE PRODUCTIVE LANDSCAPE IN DIBEEN KBA SITUATION ANALYSIS AND MEASURES IDENTIFICATION AMJAD AND MAJDI SALAMEH COMPANY ENVIROMATICS Amman, Jordan Contents Executive summary ................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1 Present Situation and Trends ................................................................................. 5 Land cover and ecological character of the study area ............................................................... 5 Closed old-growth forests ....................................................................................................... 5 Open old-growth forests ......................................................................................................... 5 Non-forest Mediterranean habitats (also referred to as marginal undeveloped land) .......... 6 Planted (Man-made) forests ................................................................................................... 6 Wadi systems ........................................................................................................................... 6 Zarqa River and King Talal Dam ............................................................................................... 6 Mix-use rural agricultural areas (Orchids) and Farmlands (crop plantations) ........................ 7 Urban areas ............................................................................................................................ -

Women's Political Participation in Jordan

MENA - OECD Governance Programme WOMEN’S Political Participation in JORDAN © OECD 2018 | Women’s Political Participation in Jordan | Page 2 WOMEN’S POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN JORDAN: BARRIERS, OPPORTUNITIES AND GENDER SENSITIVITY OF SELECT POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS MENA - OECD Governance Programme © OECD 2018 | Women’s Political Participation in Jordan | Page 3 OECD The mission of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is to promote policies that will improve the economic and social well-being of people around the world. It is an international organization made up of 37 member countries, headquartered in Paris. The OECD provides a forum in which governments can work together to share experiences and seek solutions to common problems within regular policy dialogue and through 250+ specialized committees, working groups and expert forums. The OECD collaborates with governments to understand what drives economic, social and environmental change and sets international standards on a wide range of things, from corruption to environment to gender equality. Drawing on facts and real-life experience, the OECD recommend policies designed to improve the quality of people’s. MENA - OECD MENA-OCED Governance Programme The MENA-OECD Governance Programme is a strategic partnership between MENA and OECD countries to share knowledge and expertise, with a view of disseminating standards and principles of good governance that support the ongoing process of reform in the MENA region. The Programme strengthens collaboration with the most relevant multilateral initiatives currently underway in the region. In particular, the Programme supports the implementation of the G7 Deauville Partnership and assists governments in meeting the eligibility criteria to become a member of the Open Government Partnership. -

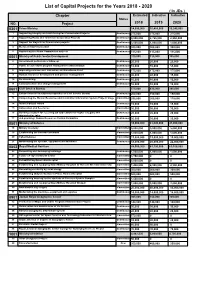

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2018 2019 2020 0301 Prime Ministry 14,090,000 10,455,000 10,240,000 1 Supporting Integrity and Anti-Corruption Commission Projects Continuous 275,000 275,000 275,000 2 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 9,900,000 8,765,000 8,550,000 3 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 4 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 5 Supporting the Media Commission projects Continuous 115,000 115,000 115,000 0501 Ministry of Public Sector Development 310,000 310,000 305,000 6 Government performance follow up Continuous 20,000 20,000 20,000 7 Public sector reform program management administration Continuous 55,000 55,000 55,000 8 Improving services and Innovation and Excellence Fund Continuous 175,000 175,000 175,000 9 Human resources development and policies management Continuous 40,000 40,000 35,000 10 Re-structuring Continuous 10,000 10,000 10,000 11 Communication and change management Continuous 10,000 10,000 10,000 0601 Civil Service Bureau 575,000 435,000 345,000 12 Enhancement of institutional capacities of Civil Service Bureau Continuous 200,000 150,000 150,000 13 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Project/ Stage Committed 290,000 200,000 110,000 2 14 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 15 Automation and E-services Committed 30,000 30,000 30,000 16 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 20,000 20,000 20,000 administrative jobs. -

Development Report 2015

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. JORDAN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2015 REGIONAL DISPARITIES JORDAN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2015 Regional Disparities Jordan Human Development Report 2015: Regional Disparities Project Board Members Mukhallad Omari, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation Zena Ali Ahmad, UNDP-Jordan Mohammad Nabulsi, Economic and Social Council National Reviewers Mukhallad Omari, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation Basem Kanan, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation Diya Elfadel, UNDP-Jordan Zein Soufan, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation Orouba Al-Sabbagh, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation Raedah Frehat, Jordanian National Commission for Women Junnara Murad, Development and Employment Fund Ahmad Al-Qubelat, Department of Statistics Maisoon Amarneh, Jordan Economic and Social Council Osama Al-Salaheen, Ministry of Social Development Reem Al-Zaben, Jordanian Hashemite Fund for Human Development Ali Al-Metleq, The Higher Population Council Laith Al-Qasem Abdelbaset Al-Thamnah, Department of Statistics JORDAN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2015 1 Jordan Human Development Report 2015: Regional Disparities International reviewers Selim Jahan, Director, Human Development Report Ofce Jon Hall, Policy Specialist, National Human Development Reports, UNDP Consultants Core Team of Writers Khalid W. Al-Wazani- Chief Researcher and Team Leader (Issnaad Consulting) Ahmad AL-Shoqran, Report Coordinator (Issnaad Consulting) Ibrahim Aljazy Alaa Bashaireh Other Participating Experts Fawaz Al-Momani Abdallah Ababneh Abdelbaset Al-Thamnah Fairouz Aldahmour Mohammad Bani Salameh Naser Abu Zayton Hani Kurdi Mohammad Nassrat Salma Nims Survey Team Naser Abu Zayton Taqwah Saleh Ebtisam Abdullah Issnaad Consulting Management advisory services Ahmad Hindawi Lara Khozouz Lana Mattar Taqwah Saleh 2 JORDAN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2015 Jordan Human Development Report 2015: Regional Disparities Jordan Human Development Report 2015: Regional Disparities No. -

Jordan 2019 Human Rights Report

JORDAN 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is a constitutional monarchy ruled by King Abdullah II bin Hussein. The constitution grants the king ultimate executive and legislative authority. The multiparty parliament consists of the 65-member Senate (Majlis al-Ayan) appointed by the king and a 130-member popularly elected House of Representatives (Majlis al-Nuwwab). Elections for the House of Representatives occur approximately every four years and last took place in 2016. International observers deemed the elections organized, inclusive, credible, and technically well run. The Public Security Directorate (PSD) has responsibility for law enforcement and reports to the Ministry of Interior. The PSD, General Intelligence Directorate (GID), gendarmerie, and Civil Defense Directorate share responsibility for maintaining internal security. The gendarmerie and Civil Defense Directorate report to the Ministry of Interior, while the GID reports directly to the king. The armed forces report to the Ministry of Defense and are responsible for external security, although they also have a support role for internal security. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Significant human rights issues included: allegations of torture by security officials; arbitrary arrest and detention, including of activists and journalists; infringements on citizens’ privacy rights; restrictions on free expression and the press, including criminalization of libel, censorship, and internet site blocking; restrictions on freedom of association and assembly; incidents of official corruption; “honor” killings of women; violence against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) persons; and conditions amounting to forced labor in some sectors. Impunity remained widespread, although the government took limited, nontransparent steps to investigate, prosecute, and punish officials who committed abuses. -

Jordan 2020 Human Rights Report

JORDAN 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is a constitutional monarchy ruled by King Abdullah II bin Hussein. The constitution grants the king ultimate executive and legislative authority. The multiparty parliament consists of a 130-member popularly elected House of Representatives (Majlis al-Nuwwab) and a Senate (Majlis al-Ayan) appointed by the king. Elections for the House of Representatives occur approximately every four years and last took place on November 10. Local nongovernmental organizations reported some COVID-19- related disruptions during the election process but stated voting was generally free and fair. Jordan’s security services underwent a significant reorganization in December 2019 when the king combined the previously separate Public Security Directorate (police), the Gendarmerie, and the Civil Defense Directorate into one organization named the Public Security Directorate. The reorganized Public Security Directorate has responsibility for law enforcement and reports to the Ministry of Interior. The Public Security Directorate and the General Intelligence Directorate share responsibility for maintaining internal security. The General Intelligence Directorate reports directly to the king. The armed forces report to the Minister of Defense and are responsible for external security, although they also have a support role for internal security. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Members of the security forces committed some abuses. Significant