Download Complete [PDF]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISI in Pakistan's Domestic Politics

ISI in Pakistan’s Domestic Politics: An Assessment Jyoti M. Pathania D WA LAN RFA OR RE F S E T Abstract R U T D The articleN showcases a larger-than-life image of Pakistan’s IntelligenceIE agencies Ehighlighting their role in the domestic politics of Pakistan,S C by understanding the Inter-Service Agencies (ISI), objectives and machinations as well as their domestic political role play. This is primarily carried out by subverting the political system through various means, with the larger aim of ensuring an unchallenged Army rule. In the present times, meddling, muddling and messing in, the domestic affairs of the Pakistani Government falls in their charter of duties, under the rubric of maintenance of national security. Its extra constitutional and extraordinary powers have undoubtedlyCLAWS made it the potent symbol of the ‘Deep State’. V IC ON TO ISI RY H V Introduction THROUG The incessant role of the Pakistan’s intelligence agencies, especially the Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI), in domestic politics is a well-known fact and it continues to increase day by day with regime after regime. An in- depth understanding of the subject entails studying the objectives and machinations, and their role play in the domestic politics. Dr. Jyoti M. Pathania is Senior Fellow at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi. She is also the Chairman of CLAWS Outreach Programme. 154 CLAWS Journal l Winter 2020 ISI IN PAKISTAN’S DOMESTIC POLITICS ISI is the main branch of the Intelligence agencies, charged with coordinating intelligence among the -

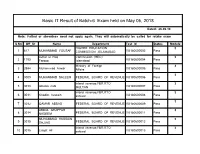

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam Held on May 05, 2018

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam S.No Off_Sr Name Department Test Id Status Module HIGHER EDUCATION 3 1 617 MUHAMMAD YOUSAF COMMISSION ,ISLAMABAD VU180600002 Pass Azhar ul Haq Commission (HEC) 3 2 1795 Farooq Islamabad VU180600004 Pass Ministry of Foreign 3 3 2994 Muhammad Anwar Affairs VU180600005 Pass 3 4 3009 MUHAMMAD SALEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600006 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 5 3010 Ghulan nabi MULTAN VU180600007 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 6 3011 Khadim hussain sahiwal VU180600008 Pass 3 7 3012 QAMAR ABBAS FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600009 Pass ABDUL GHAFFAR 3 8 3014 NADEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600011 Pass MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN 3 9 3015 SAJJAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600012 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 10 3016 Liaqat Ali sahiwal VU180600013 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 11 3017 Tariq javed sahiwal VU180600014 Pass 3 12 3018 AFTAB AHMAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600015 Pass Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Muhammad inam-ul- inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 13 3019 haq MULTAN VU180600016 Pass Ministry of Defense (Defense Division) 3 Rawalpindi. 14 4411 Asif Mehmood VU180600018 Pass 3 15 4631 Rooh ul Amin Pakistan Air Force VU180600022 Pass Finance/Income Tax 3 16 4634 Hammad Qureshi Department VU180600025 Pass Federal Board Of Revenue 3 17 4635 Arshad Ali Regional Tax-II VU180600026 Pass 3 18 4637 Muhammad Usman Federal Board Of Revenue VU180600027 -

Transparency International Pakistan Is Striving for Across the Board Application of Rule of Law, Which Is the Only Way to Stop Corruption

5-C, 2nd Floor, Khayaban-e-lttehad, Ph3se VII, Defence Housing Authority, Karachi. ~TRANSPARENCY Tel : (92-21)-35390408, 35390409, Fax: 35390410 ~ INTERNATIONAL-PAKISTAN E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.transparency.org.pk 8111 November, 2016 TL16/0811/7A Officer Commanding, Airport Road, Nur Khan Chowk, VIP Guard Room, PAF Base Nur Khan, Chaklala, Rawalpindi Telephone# 051-9525031. Sub: Violation of Public Procurement Rules 2004, Officer Commanding, P AF Base Nur Khan's Tender Notices for Petrol Pumps. Dear Sir, This is with reference to PAF Base Nur Khan's Tender Notices published in daily "The News" on i 11 November, 2016. It is observed that the advertisements are in violation of the Public Procurement Rules 2004. As per the advertisement, the bid receiving date is given as 18-11-2016, while the bid opening date is given as 19-11-2016. Therefore the advertisement is in violation of PPRA Rules 2004, Rule 28(1 ). Stated as under; 28. Opening of bids. - (1) The date for opening of bids and the last date for the submission of bids shall be the same. Bids shall be opened at the time specified in the bidding documents. The bids shall be opened at least thirty minutes after the deadline for submission ofbids. The above infom1ation is forwarded for the purpose of avoiding mis-procurement charge under Rule No 50, and with request to re-invite the tenders under the prescribed procedures or issue a corrigendum and extend date accordingly. Transparency International Pakistan is striving for across the board application of Rule of Law, which is the only way to stop corruption. -

Chinese Policy Towards Pakistan, 1969-1979

CHINESE POLICY TOWARDS PAKISTAN (1969 - 1979) by Samina Yasmeen Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania April 1985 CONTENTS INTHODUCTION 1 PART ONE CHAPTER I 7 CHINESE POLICY TOWARDS PAKISTAN DURING THE 1950s 7 CHAPTER II 31 CHINESE POLICY TOWARDS PAKISTAN DURING THE 1960-68 PERIOD 31 Keeping the Options Open 31 Cautious Move to Friendship 35 Consolidation of a Friendship 38 The Indo-Pakistan War (1965) and China 63 The Post-War Years 70 Conclusion 72 PART TWO CHAPTER III 74 FROM UNQUALIFIED TO QUALIFIED SUP PORT: THE KASJ-IMIIl DISPUTE 75 China and the Kashmir Issue: 1969-1971 76 The Bhutto Regime - The Kashmir Issue and China 85 The Zia Regime - The Kashmir Issue and China 101 CHAPTER IV FROM QUALIFIED TO UNQUALIFIED SUPPORT: EAST PAKISTAN CRISIS (1971) 105 The Crisis - India, Pakistan and China's Initial Reaction 109 Continuation of a Qualified Support 118 A Change in Support: Qualified to Unqualified 129 Conclusion 138 CHAPTER V 140 UNQUALIFIED SUPPORT: CHINA AND THE 'NEW' PAKISTAN'S PROBLEMS DECEMBER 1971-APRIL 1974 140 Pakistan's Problems 141 Chinese Support for Pakistan 149 Significance of Chinese Support 167 Conclusion 17 4 CHAPTER VI 175 CAUTION AMIDST CONTINUITY: CHINA, THE INDIAN NUCLEAR TEST AND A PROPOSED NUCLEAR FREE SOUTH ASIA 175 Indian Nuclear Explosion 176 Nuclear-Free Zone in South Asia 190 Conclusion 199 CHAPTER VII 201 PAKISTAN AND THE SAUR REVOLUTION IN AFGHANISTAN (1978): CHINESE RESPONSES 201 The Saur Revolution and Pakistan's Threat Perceptions -

Paf Celebrates Golden Jubilee of Defence Day

PAF CELEBRATES GOLDEN JUBILEE OF DEFENCE DAY Islamabad 06 September, 2015:- Defence Day of Pakistan was celebrated at all PAF Bases in a befitting manner. The year has been marked as the Golden Jubilee of 1965 war, when PAF vanquished a three times large Indian Air Force and wrote an epic of unmatched valor and sacrifice. The auspicious day was observed with a renewed pledge and determination to make “Fizaia” even more stronger and potent force to face any challenge. The day started with special Du’a and Quran Khawani for the Shahuda at all PAF Bases. A special feature of the day was the change of guards ceremony at the Mazar of Quaid-e-Azam in Karachi. Aviation Cadets from Pakistan Air Force Academy, Risalpur assumed guard duties at the Mazar to honour the Father of the Nation. On the occasion of Defence Day Air Chief Marshal Sohail Aman, Chief of the Air Staff, Pakistan Air Force said in his message, “We are a resilient nation, which has always proved its worth in difficult times, whether those were natural calamities or an imposed armed conflict, as in 1965. Though, we are a peace loving nation, but we know how to thwart the heinous attempts that disrupt our peaceful way of life and certainly, our strength is in this resolve. Today, let us re- pledge to make Pakistan a truly dynamic and prosperous country by firmly following the great Quaid’s golden principles of Unity, Faith and Discipline as our national ideals. On this occasion, I would like to assure you that Pakistan Air Force, with state-of-the-art equipment on its inventory and a highly capable workforce, is fully prepared to defend the aerial frontiers of its motherland”. -

Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE for AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi

AIR POWER Journal of Air Power and Space Studies Vol. 3, No. 3, Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE FOR AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi AIR POWER is published quarterly by the Centre for Air Power Studies, New Delhi, established under an independent trust titled Forum for National Security Studies registered in 2002 in New Delhi. Board of Trustees Shri M.K. Rasgotra, former Foreign Secretary and former High Commissioner to the UK Chairman Air Chief Marshal O.P. Mehra, former Chief of the Air Staff and former Governor Maharashtra and Rajasthan Smt. H.K. Pannu, IDAS, FA (DS), Ministry of Defence (Finance) Shri K. Subrahmanyam, former Secretary Defence Production and former Director IDSA Dr. Sanjaya Baru, Media Advisor to the Prime Minister (former Chief Editor Financial Express) Captain Ajay Singh, Jet Airways, former Deputy Director Air Defence, Air HQ Air Commodore Jasjit Singh, former Director IDSA Managing Trustee AIR POWER Journal welcomes research articles on defence, military affairs and strategy (especially air power and space issues) of contemporary and historical interest. Articles in the Journal reflect the views and conclusions of the authors and not necessarily the opinions or policy of the Centre or any other institution. Editor-in-Chief Air Commodore Jasjit Singh AVSM VrC VM (Retd) Managing Editor Group Captain D.C. Bakshi VSM (Retd) Publications Advisor Anoop Kamath Distributor KW Publishers Pvt. Ltd. All correspondence may be addressed to Managing Editor AIR POWER P-284, Arjan Path, Subroto Park, New Delhi 110 010 Telephone: (91.11) 25699131-32 Fax: (91.11) 25682533 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.aerospaceindia.org © Centre for Air Power Studies All rights reserved. -

Ladakh Travels Far and Fast

LADAKH TRAVELS FAR AND FAST Sat Paul Sahni In half a century, Ladakh has transformed itself from the medieval era to as modern a life as any in the mountainous regions of India. Surely, this is an incredible achievement, unprecedented and even unimagin- able in the earlier circumstances of this landlocked trans-Himalayan region of India. In this paper, I will try and encapsulate what has happened in Ladakh since Indian independence in August 1947. Independence and partition When India became independent in 1947, the Ladakh region was cut off not only physically from the rest of India but also in every other field of human activity except religion and culture. There was not even an inch of proper road, although there were bridle paths and trade routes that had been in existence for centuries. Caravans of donkeys, horses, camels and yaks laden with precious goods and commodities had traversed the routes year after year for over two millennia. Thousands of Muslims from Central Asia had passed through to undertake the annual Hajj pilgrimage; and Buddhist lamas and scholars had travelled south to Kashmir and beyond, as well as towards Central Tibet in pursuit of knowledge and religious study and also for pilgrimage. The means of communication were old, slow and outmoded. The postal service was still through runners and there was a single telegraph line operated through Morse signals. There were no telephones, no newspapers, no bus service, no electricity, no hospitals except one Moravian Mission doctor, not many schools, no college and no water taps. In the 1940s, Leh was the entrepôt of this part of the world. -

Comparative Constitutional Law SPRING 2012

Comparative Constitutional Law SPRING 2012 PROFESSOR STEPHEN J. SCHNABLY Office: G472 http://osaka.law.miami.edu/~schnably/courses.html Tel.: 305-284-4817 E-mail: [email protected] SUPPLEMENTARY READINGS: TABLE OF CONTENTS Reference re Secession of Quebec, [1998] 2 S.C.R. 217 .................................................................1 Supreme Court Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. S-26. An Act respecting the Supreme Court of Canada................................................................................................................................11 INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983) .............................................................................................12 Kenya Timeline..............................................................................................................................20 Laurence Juma, Ethnic Politics and the Constitutional Review Process in Kenya, 9 Tulsa J. Comp. & Int’l L. 471 (2002) ..........................................................................................23 Mary L. Dudziak, Working Toward Democracy: Thurgood Marshall and the Constitution of Kenya, 56 Duke L.J. 721 (2006)....................................................................................26 Laurence Juma, Ethnic Politics and the Constitutional Review Process in Kenya, 9 Tulsa J. Comp. & Int’l L. 471 (2002) .......................................................................................34 Migai Akech, Abuse of Power and Corruption in Kenya: Will the New Constitution Enhance Government -

Aircraft Collection

A, AIR & SPA ID SE CE MU REP SEU INT M AIRCRAFT COLLECTION From the Avenger torpedo bomber, a stalwart from Intrepid’s World War II service, to the A-12, the spy plane from the Cold War, this collection reflects some of the GREATEST ACHIEVEMENTS IN MILITARY AVIATION. Photo: Liam Marshall TABLE OF CONTENTS Bombers / Attack Fighters Multirole Helicopters Reconnaissance / Surveillance Trainers OV-101 Enterprise Concorde Aircraft Restoration Hangar Photo: Liam Marshall BOMBERS/ATTACK The basic mission of the aircraft carrier is to project the U.S. Navy’s military strength far beyond our shores. These warships are primarily deployed to deter aggression and protect American strategic interests. Should deterrence fail, the carrier’s bombers and attack aircraft engage in vital operations to support other forces. The collection includes the 1940-designed Grumman TBM Avenger of World War II. Also on display is the Douglas A-1 Skyraider, a true workhorse of the 1950s and ‘60s, as well as the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and Grumman A-6 Intruder, stalwarts of the Vietnam War. Photo: Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum GRUMMAN / EASTERNGRUMMAN AIRCRAFT AVENGER TBM-3E GRUMMAN/EASTERN AIRCRAFT TBM-3E AVENGER TORPEDO BOMBER First flown in 1941 and introduced operationally in June 1942, the Avenger became the U.S. Navy’s standard torpedo bomber throughout World War II, with more than 9,836 constructed. Originally built as the TBF by Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, they were affectionately nicknamed “Turkeys” for their somewhat ungainly appearance. Bomber Torpedo In 1943 Grumman was tasked to build the F6F Hellcat fighter for the Navy. -

Gwadar: China's Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons CMSI China Maritime Reports China Maritime Studies Institute 8-2020 China Maritime Report No. 7: Gwadar: China's Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan Isaac B. Kardon Conor M. Kennedy Peter A. Dutton Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports Recommended Citation Kardon, Isaac B.; Kennedy, Conor M.; and Dutton, Peter A., "China Maritime Report No. 7: Gwadar: China's Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan" (2020). CMSI China Maritime Reports. 7. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the China Maritime Studies Institute at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in CMSI China Maritime Reports by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. August 2020 iftChina Maritime 00 Studies ffij$i)f Institute �ffl China Maritime Report No. 7 Gwadar China's Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan Isaac B. Kardon, Conor M. Kennedy, and Peter A. Dutton Series Overview This China Maritime Report on Gwadar is the second in a series of case studies on China’s Indian Ocean “strategic strongpoints” (战略支点). People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials, military officers, and civilian analysts use the strategic strongpoint concept to describe certain strategically valuable foreign ports with terminals and commercial zones owned and operated by Chinese firms.1 Each case study analyzes a different port on the Indian Ocean, selected to capture geographic, commercial, and strategic variation.2 Each employs the same analytic method, drawing on Chinese official sources, scholarship, and industry reporting to present a descriptive account of the port, its transport infrastructure, the markets and resources it accesses, and its naval and military utility. -

F—18 Navy Air Combat Fighter

74 /2 >Af ^y - Senate H e a r tn ^ f^ n 12]$ Before the Committee on Appro priations (,() \ ER WIIA Storage ime nts F EB 1 2 « T H e -,M<rUN‘U«sni KAN S A S S F—18 Na vy Air Com bat Fighter Fiscal Year 1976 th CONGRESS, FIRS T SES SION H .R . 986 1 SPECIAL HEARING F - 1 8 NA VY AIR CO MBA T FIG H TER HEARING BEFORE A SUBC OMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE NIN ETY-FOURTH CONGRESS FIR ST SE SS IO N ON H .R . 9 8 6 1 AN ACT MAKIN G APP ROPR IA TIO NS FO R THE DEP ARTM EN T OF D EFEN SE FO R T H E FI SC AL YEA R EN DI NG JU N E 30, 1976, AND TH E PE RIO D BE GIN NIN G JU LY 1, 1976, AN D EN DI NG SEPT EM BER 30, 1976, AND FO R OTH ER PU RP OSE S P ri nte d fo r th e use of th e Com mittee on App ro pr ia tio ns SPECIAL HEARING U.S. GOVERNM ENT PRINT ING OFF ICE 60-913 O WASHINGTON : 1976 SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS JOHN L. MCCLELLAN, Ark ans as, Chairman JOH N C. ST ENN IS, Mississippi MILTON R. YOUNG, No rth D ako ta JOH N O. P ASTORE, Rhode Island ROMAN L. HRUSKA, N ebraska WARREN G. MAGNUSON, Washin gton CLIFFORD I’. CASE, New Je rse y MIK E MANSFIEL D, Montana HIRAM L. -

Company Profile

Shaheen Medical Services, Opposite Benazir Bhutto Airport Chaklala, Rawalpindi Phone: +92-51-5405270,5780328, PAF: 3993 http://shaheenmedicalservices.com / Email: [email protected] Page 1 MISSION Gain trust of our valuable clients, with most efficient and ethical services, by providing quality pharmaceutical products with maximum shelf life procured from authentic sources. VISION SMS is continuously striving to be recognized as a leading distributor of pharmaceutical products by focusing on efficient and ethical delivery of services. GOAL To work in collaboration with our worthy partners, to provide high value and premium quality pharmaceutical products to our clients, in order to sustain long-term business relationship. Shaheen Medical Services, Opposite Benazir Bhutto Airport Chaklala, Rawalpindi Phone: +92-51-5405270,5780328, PAF: 3993 http://shaheenmedicalservices.com / Email: [email protected] Page 2 INTRODUCTION Shaheen Foundation, Pakistan Air Force (PAF), was established in 1977 under the Charitable Endowment Act, 1890, essentially to promote welfare for the benefit of serving and retired PAF personnel including its civilian’s employees and their dependents, and to this end generates funds through industrial and commercial enterprises. Since then, it has launched a number of profitable ventures to generate funds necessary for financing the Foundation’s welfare activities. Shaheen Medical Services (SMS) was established to fulfill the pharmaceutical and surgical requirement of Armed forces and public/private sector. Since it’s founding in Rawalpindi in 1996, Shaheen Medical Services, Shaheen Foundation, PAF has become the leading distributor of Pharmaceuticals & Surgical products in Pakistan Air Force Hospitals, with offices in 22 cities nationwide. SMS is a registered member of Rawalpindi Chamber of Commerce and Industries (RCC&I), Export Promotion Bureau (EPB) of Pakistan and Director General Defense Purchase (DGDP).