Ladakh Travels Far and Fast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE for AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi

AIR POWER Journal of Air Power and Space Studies Vol. 3, No. 3, Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE FOR AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi AIR POWER is published quarterly by the Centre for Air Power Studies, New Delhi, established under an independent trust titled Forum for National Security Studies registered in 2002 in New Delhi. Board of Trustees Shri M.K. Rasgotra, former Foreign Secretary and former High Commissioner to the UK Chairman Air Chief Marshal O.P. Mehra, former Chief of the Air Staff and former Governor Maharashtra and Rajasthan Smt. H.K. Pannu, IDAS, FA (DS), Ministry of Defence (Finance) Shri K. Subrahmanyam, former Secretary Defence Production and former Director IDSA Dr. Sanjaya Baru, Media Advisor to the Prime Minister (former Chief Editor Financial Express) Captain Ajay Singh, Jet Airways, former Deputy Director Air Defence, Air HQ Air Commodore Jasjit Singh, former Director IDSA Managing Trustee AIR POWER Journal welcomes research articles on defence, military affairs and strategy (especially air power and space issues) of contemporary and historical interest. Articles in the Journal reflect the views and conclusions of the authors and not necessarily the opinions or policy of the Centre or any other institution. Editor-in-Chief Air Commodore Jasjit Singh AVSM VrC VM (Retd) Managing Editor Group Captain D.C. Bakshi VSM (Retd) Publications Advisor Anoop Kamath Distributor KW Publishers Pvt. Ltd. All correspondence may be addressed to Managing Editor AIR POWER P-284, Arjan Path, Subroto Park, New Delhi 110 010 Telephone: (91.11) 25699131-32 Fax: (91.11) 25682533 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.aerospaceindia.org © Centre for Air Power Studies All rights reserved. -

Insights Into the P–T Evolution Path of Tso Morari Eclogites of the North-Western Himalayas: Constraints on the Geodynamic Evolution of the Region

Insights into the P–T evolution path of Tso Morari eclogites of the north-western Himalayas: Constraints on the geodynamic evolution of the region Preeti Singh, Ashima Saikia∗, Naresh Chandra Pant and Pramod Kumar Verma∗∗ Department of Geology, University of Delhi, Delhi 110 007, India. ∗Corresponding author. e-mail: [email protected] The present study is on the Ultra High Pressure Metamorphic rocks of the Tso Morari Crystalline Com- plex of the northwestern Himalayas. Five different mineral associations representative of five stages of P–T (pressure–temperature) evolution of these rocks have been established based on metamorphic tex- tures and mineral chemistry. The pre-UHP metamorphic association 1 of Na-Ca-amphibole + epidote ± paragonite ± rutile ± magnetite with T–P of ∼ 500◦C and 10 kbar. This is followed by UHP metamor- phic regime marked by association 2 and association 3. Association 2 (Fe>Mg>Ca-garnet + omphacite + coesite + phengite + rutile ± ilmenite) marks the peak metamorphic conditions of atleast 33 kbar and ∼ 750◦C. Association 3 (Fe>Mg>Ca-garnet + Na-Ca amphibole + phengite ± paragonite ± calcite ± ilmenite ± titanite) yields a P–T condition of ∼28 kbar and 700◦C. The post-UHP metamorphic regime is defined by associations 4 and 5. Association 4 (Fe>Ca>Mg-garnet + Ca-amphibole + plagioclase (An05) + biotite + epidote ± phengite yields a P–T estimate of ∼14 kbar and 800◦C) and association 5 (Chlorite + plagioclase (An05) + quartz + phengite + Ca-amphibole ± epidote ± biotite ± rutile ± titanite ± ilmenite) yields a P–T value of ∼7 kbar and 350◦C. 1. Introduction (UHPM) and their subsequent exhumation and preservation at surface conditions (e.g., UHPM Reported occurrence of coesite, the high pressure rocks from the Kokchetav massif, Kazakhstan; polymorph of quartz as inclusions in the garnets Dabie-Shan, China and western Gneiss Region, of eclogitic rocks from Norway and the Alps region Norway, Dora Maria Massif, W. -

![Download Complete [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6761/download-complete-pdf-896761.webp)

Download Complete [PDF]

Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi-110010 Journal of Defence Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.idsa.in/journalofdefencestudies Critical Analysis of Pakistani Air Operations in 1965: Weaknesses and Strengths Arjun Subramaniam To cite this article: Arjun Subramaniam (201 5): Critical Analysis of Pakistani Air Op erations in 1965: Weaknesses and Strengths, Journal of Defence Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3 July-September 2015, pp. 95-113 URL http://idsa.in/jds/9_3_2015_CriticalAnalysisofPakistaniAirOperationsin1965.html Please Scroll down for Article Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.idsa.in/termsofuse This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re- distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India. Critical Analysis of Pakistani Air Operations in 1965 Weaknesses and Strengths Arjun Subramaniam* This article tracks the evolution of the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) into a potent fighting force by analysing the broad contours of joint operations and the air war between the Indian Air Force (IAF) and PAF in 1965. Led by aggressive commanders like Asghar Khan and Nur Khan, the PAF seized the initiative in the air on the evening of 6 September 1965 with a coordinated strike from Sargodha, Mauripur and Peshawar against four major Indian airfields, Adampur, Halwara, Pathankot and Jamnagar. -

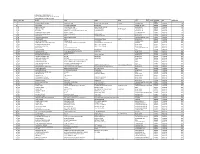

Jamna Auto Industries Ltd List of Shareholders As on 23-03-18 for Tranfer to Iepf Account Sr.No Folio No Name Add1 Add2 Add3

JAMNA AUTO INDUSTRIES LTD LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS AS ON 23-03-18 FOR TRANFER TO IEPF ACCOUNT SR.NO FOLIO_NO NAME ADD1 ADD2 ADD3 CITY STATE COUNTRYPINCODE Type SHR230318 Total 1 7 KULDEEP SINGH BHATIA KOTHI NO 1768 PHASE 3 B-II SAS NAGAR MOHALI CHANDIGARH 000000 PHYSICAL 100 2 8 RAJ KUMAR K R STEEL PRODUCTS BURIA GATE JAGADHRI (HRY) 000000 PHYSICAL 100 3 10 SANTOSH AHUJA C/O COL VK AHUJA NEW BHOPAL TEXTILE BHOPAL (M P) 462001 PHYSICAL 100 4 13 JASWANT KAUR C/O S SURJEET SINGH CHEEMA HOUSE PREM NAGAR PATIALA (P B) 000000 PHYSICAL 100 5 14 G S MANN MANN VILLA 22 NEW OFFICER COLONY STADIUM ROAD PATIALA (P B) 000000 PHYSICAL 100 6 17 HARMINDER PAUL SINGH MODEL TOWN JALANDHAR (P B) 000000 PHYSICAL 100 7 18 HARDEV BAHADUR SINGH AJMAL KHAN ROAD KAROL BAGH NEW DELHI 000000 PHYSICAL 100 8 20 SARLADEVI E-255 GREATER KAILASH NEW DELHI 110048 PHYSICAL 100 9 22 MADHU BHATNAGAR PAPER MILL COLONY YAMUNA NAGAR (HRY.) 135001 PHYSICAL 100 10 26 KANTA SOBTI A-90 GUJRAWALA TOWN PART - I NEW DELHI 000000 PHYSICAL 100 11 121 LAJPAT RAI CHOPRA HOUSE NO 15 SECTOR-8A CHANDIGARH 000000 PHYSICAL 6000 12 155 BHAGWAN DAS L MOLCHANDANI C/O MODERN TRADING CO (BOMBAY) FATCH MANZIL OPERA HOUSE MUMBAI 400001 PHYSICAL 3000 13 180 GURMINDER KAUR DILER 17/9 WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI 110008 PHYSICAL 2000 14 187 RAVINDER KAUR DILER 17/9 WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI 110008 PHYSICAL 2000 15 267 VERA SINGH VILLAGE AMADALPUR JAGADHRI (HARYANA) 000000 PHYSICAL 3000 16 286 ASHOK KUMAR LP 32 A MRURAYA ENCLAVE PITAM PURA DELHI 110034 PHYSICAL 2500 17 308 CHAMAN SINGH C-187 MANSAROVER GARDEN -

TA 7417- IND: Support for the National Action Plan on Climate Change

TA7417-IND Support for the National Action Plan for Climate Change Support to the National Water Mission TA 7417 - IND: Support for the National Action Plan on Climate Change Support to the National Water Mission Final Report September 2011 Appendix 1 India Water Systems PREPARED FOR Government of India Governments of Punjab, Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu Asian Development Bank Support to the National Water Mission NAPCC ii Appendix 1 India Water Systems Appendix 1 India Water Systems Support to the National Water Mission NAPCC ii Appendix 1 India Water Systems Support to the National Water Mission NAPCC iii Appendix 1 India Water Systems SUMMARY OF ABBREVIATIONS A1B IPCC Climate Change Scenario A1 assumes a world of very rapid economic growth, a global population that peaks in mid-century and rapid introduction of new and more efficient technologies. A1 is divided into three groups that describe alternative directions of technological change: fossil intensive (A1FI), non-fossil energy resources (A1T) and a balance across all sources (A1B). A2 IPCC climate change Scenario A2 describes a very heterogeneous world with high population growth, slow economic development and slow technological change. ADB Asian Development Bank AGTC Agriculture Technocrats Action Committee of Punjab AOGCM Atmosphere Ocean Global Circulation Model APHRODITE Asian Precipitation - Highly-Resolved Observational Data Integration Towards Evaluation of Water Resources - a observed gridded rainfall dataset developed in Japan APN Asian Pacific Network for Global Change Research AR Artificial Recharge AR4 IPCC Fourth Assessment Report AR5 IPCC Fifth Assessment Report AWM Adaptive Water Management B1 IPCC climate change Scenario B1 describes a convergent world, with the same global population as A1, but with more rapid changes in economic structures toward a service and information economy. -

Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru Series 2, Volume 60

Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru Series 2, Volume 60 April 15- May 31, 1960 1. Members of the Chinese Delegation1 Jagat Mehta from Kannampilly Chinese Foreign Office handed over following list of Chou En-lai's party. Begins: 1. Chou En-lai Premier of the State Council. 2. Chen Yi Vice Premier of the State Council and Minister for Foreign Affairs. 3. Chang Han-fu Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs. 4. ChangYen Deputy Director of the Office in Charge of Foreign Affairs, State Council. 5. Chiao Kuan-hua Assistant Minister for Foreign Affairs. 6. Lo Ching-chang Deputy Director of the Premier's Secretariat. 7. Chang Wen-chin Director of the First Asian Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 8. Kang Mao-chao Deputy Director of the Indo Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 9. Li Shu-huai Department Deputy Director, Ministry of Public Security. 1 Telegram from K.M. Kannampilly, Charge d' Affaires, Indian Embassy, Peking, to Jagat Mehta, Director, Northern Division, MEA, 7 April 1960. This volume begins on 15 April but three items dated 7, 8 and 14 April have been included here as they pertain to Chou's visit. 10.Huag Shu-tsu Deputy Director of the Health Protection Bureau, Ministry of Public Health. 11. Chou Chia-ting Secretary of the Premier's Secretariat. 12. Pu Shou-chang Secretary of the Premier's Secretariat. 13. HoChien Secretary of the Premier's Secretariat. 14. Han Hsu Assistant Director of the Protocol Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 15. Ma Lieh Secretary of the Premier's Secretariat. 16. Ni Yung Heh Assistant Director of the First Asian Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. -

Magazine1-4 Final.Qxd (Page 2)

Restore Geological ...Page 4 SUNDAY, MAY 17, 2020 INTERNET EDITION : www.dailyexcelsior.com/sunday-magazine Making Spirituality...Page 3 Saint, Scholar from Ladakh Nawang Tsering Shakspo With that, Prime Minister Bakshi inducted Kushok Bakula into his ministry and accordingly Kushok Bakula Rinpoche became Deputy Minister with the portfolio of Ladakh Affairs. According to reliable Soon after Ladakh was granted the UT status, Dr. Karan Singh, the former Sadr-i-Riyasat sources, it was none other than Nehru himself who directed Bakshi Sahib to create the Ladakh Affairs post of Jammu and Kashmir and a close associate of 19th Kushok Bakula Rinpoche, said in a state- in the Government. ment: "All empires invariably come to an end, J&K no exception." On the other hand, Kushok As the celebration of the 2500 Buddha Jayanti was drawing near, the Indian Government Bakula Rinpoche had forecast long ago that "Ladakh would attain the UT status, though there was looking for a Buddhist religious leader who could influence the Buddhist community of could be delay, adding that the destiny lies in its separation from the Jammu and Kashmir India. In 1955, the Indian Government sent Kushok Bakula to Tibet to assess the situation State". there, on account of the massive Chinese build-up in Tibet and the Red Army intrusion in that Padma Bhushan 19th Kushok Bakula Rinpoche (1917-2003), a saint and scholar from country. The Government of India also nominated Kushok Bakula as a member of the Ladakh, remained a pre-eminent religious and political figure in Ladakh for over half a cen- National Committee for Buddha Jayanti celebration in the year 1956, headed by the then tury, marked by great social and political changes. -

Page1final.Qxd (Page 2)

daily Follow us: Daily Excelsior JAMMU, FRIDAY, JULY 2, 2021 REGD. NO. JK-71/21-23 Vol No. 57 12 Pages ` 5.00 ExcelsiorRNI No. 28547/65 No. 181 AC to approve Good, digital governance prime motive of Govt: LG projects above Rs 20 cr Excelsior Correspondent Far-reaching reforms of Modi Govt JAMMU, July 1: The Government today ordered that projects above Rs 20 crore will benefitted J&K, Ladakh: Dr Jitendra be approved by the Administrative Council (AC) now onwards. Fayaz Bukhari An order to this effect was Union Ministers to start visiting UT again issued by Chief Secretary Dr SRINAGAR, July 1: Union Arun Kumar Mehta. Minister of State Develop- cers from 10 States, Dr Jitendra eral governance initiatives He brought forth the trans- As per the order, all propos- ment of North Eastern Region Singh said that Modi undertaken by the Government formational changes pursued by als for administrative approval (DoNER), MoS PMO, Government is committed to for Jammu & Kashmir including Government through the of projects above Rs 20 crore Personnel, Public Grievances, Transparency and "Justice for the long-pending cadre review, Mission Karmayogi, wherein will be placed for consideration Pensions, Atomic Energy and and approval of the Space, Dr Jitendra Singh Sinha urges all to Administrative Council after today said that many far- concurrence by the Finance reaching reforms of Modi participate in Department. Government like Prevention Delimitation meets Expert Panel to visit *Watch video on www.excelsiornews.com Excelsior Correspondent Srinagar Hospitals : DB of Corruption Act, abolition of JAMMU, July 1: Excelsior Correspondent interviews for Group C and D Lieutenant Governor Manoj A view of lightning in the sky during thunderstorm in Jammu on Thursday night which brought SRINAGAR, July 1: The posts and more than 800 Sinha today appealed to all slight relief for Jammuites from scorching heat. -

Byways Tour Packages of 2021

Byways Tour Packages of 2021 Itinerary: Srinagar- Kargil- Leh- Sangam River- Nubra Khardong La Pass - Pangong Lake via Shayok River- Tsomoriri Lake-via Tsaga la. 08 Night /09 Days. Day 01: Arrival in Srinagar After arrival at Srinagar airport, you would be transferred to hotel for check-in. Today you are free for leisure & acclimatization. Some local sightseeing and shikara ride. Dinner and overnight in hotel/houseboat. Day 02: Srinagar-Kargil Today after Breakfast, check out of the Hotel & drive to Kargil. You would be driven through Sonmarg & Drass Valley. Check-in to Hotel upon arrival. Dinner and overnight stay at Hotel. Day 03: Kargil to Leh Post Breakfast, ready to move Towards Leh. Kargil to Lamayuru monastery which is one of the oldest monastery in the region. Riding on Leh Sirnagar Highway. It have a beautiful landscape. Sangam (Indus & Zansker) river confluence, Guruth vara pathar Sahib and magnetic hill. Overnight stay hotel in Leh. Day 04: Leh- Monastery Sightseeing Shay, thiksay, Hemis monastery and Rancho School. After breakfast drive to Ladakh eastern part monastery sightseeing like Shay, thiksay, Hemis monastery. Which is famous in ladakh. Enroute visit Rancho School. Dinner and overnight stay hotel in leh. Day 05: Leh to Nubra Valley via khardong la world highest mortable pass. After early breakfast drive to Nubra valley via Khardongla Pass (18,380ft) the world’s highest motorable road and gateway to Siachen Glacier. Visit Deskit Monastery (118kms) founded by Lama Sherab Zangpo in 1420 A.D. Check in at camp or hotel and in the evening visit Hunder sand dune for camel riding, Cultural show and other activities. -

“Repair, Renovation and Restoration of Water Bodies- Encroachment on Water Bodies and Steps Required to Remove the Encroachment and Restore the Water Bodies”

10 STANDING COMMITTEE ON WATER RESOURCES (2015-16) SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENATION. “Repair, Renovation and Restoration of Water Bodies- Encroachment on Water Bodies and Steps Required to Remove the Encroachment and Restore the Water Bodies”. TENTH REPORT LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2016 / Shravana,1938 (Saka) 1 TENTH REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON WATER RESOURCES (2015-16) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENATION. “Repair, Renovation and Restoration of Water Bodies- Encroachment on Water Bodies and Steps Required to Remove the Encroachment and Restore the Water Bodies”. Presented to Lok Sabha on 02.08.2016 Laid on the Table of Rajya Sabha on 02.08.2016 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2016/ Shravana,1938 (Saka) 2 CONTENTS Part – I REPORT Page No. COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (2015-2016) (iii) INTRODUCTION (v) Chapter – I Introductory 1 Chapter – II - State of Water Bodies in the country 4 - Minor Irrigation Census 4 - Reasons for increase/ decrease in total number of water bodies 5 - Survey of water bodies by the Ministry 7 - Classification of Water Bodies 9 - Measures taken to revive perishing water bodies 12 Chapter – III - Encroachment on Water Bodies 16 - Extent of encroachment 16 - Impact of encroachment on water bodies 21 - Action against encroachers 24 - Monitoring mechanism for prevention and removal of encroachments 26 (a) Monitoring mechanism under Repair, Renovation and Restoration 26 (RRR) Scheme (b) -

Ladakh Kashmir Dossier.Pub

INCREDIBLE INDIAN TOURS Ladakh & Kashmir INCREDIBLE INDIAN TOURS Ladakh & Kashmir 22 days / 21 nights Dossier validity: 2022 - 2023 Welcome to Incredible Indian Tours’ Top of the World - Ladakh & Kashmir Tour. This is a very exotic adventure throughout the Indian Himalayas. First we journey to Ladakh through Himachal Pradesh, visiting Shimla and Manali before driving the spectacular Manali - Leh road. In and around Leh we explore the Nubra Valley, and also experience the Hemis Festival. Heading west we drive through the upper Himalayas along one of the most stunning drives in the world to Kashmir, and Srinagar, holiday mecca of India. Highlights • the splendour and contrast of the 7 cities of Delhi • the historic toy train ride up the mountain to Shimla • witness the remnants of the British Raj in Shimla • see the mountain views from the beautiful green Beas River valley in Manali • experience the spectacular Manali - Leh Highway • drive the highest motorable pass in the world - the Khardong La - at over 5600m • explore the amazing Nubra Valley in Ladakh • be part of the energetic and colourful Hemis Festival • drive the amazingly scenic Leh - Srinagar Highway • discover the monastery villages of Uleytokpo & Basgo • soak up the relaxing ambience of Dal Lake in Srinagar 2/17 www.incredibleindiatours.com E-mail: [email protected] Ph: +91 95490 02876 INCREDIBLE INDIAN TOURS Ladakh & Kashmir Itinerary Days 1-2 Delhi The tour starts at 6pm. After a short tour briefing, we head out for dinner to get to know each other and discuss the journey ahead. On day 2, we visit New Delhi - specifically Humayans Tomb, Rajpath and the Bangla Sahib Gurudwara. -

Answered On:27.07.2000 Gallantary Awards to Fighters of Kargil Conflict Simranjit Singh Mann

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DEFENCE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:667 ANSWERED ON:27.07.2000 GALLANTARY AWARDS TO FIGHTERS OF KARGIL CONFLICT SIMRANJIT SINGH MANN Will the Minister of DEFENCE be pleased to state: the total number of gallantary awards awarded to the fighters of the Kargil Conflict with full particulars of recipients? Answer MINISTER OF DEFENCE (SHRI GEORGE FERNANDES) 300 gallantry awards have so far been awarded. The details are annexed. ANNEXURE - I REFERRED TO IN REPLY GIVEN TO LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION No. 667 FOR 27.07.2000. PARTICULARS OF THE RECIPIENTS OF GALLANTRY AWARDS AWARDED ON 15.08.1999 ONACCOUNT OF KARGIL CONFLICT LIST OF RECOMMENDED CASES OF OP VIJAY : INDEPENDENCE DAY 1999 PARAM VIR CHAKRA 1. IC-57556 LT VIKRAM BATRA, 13 JAK RIF (POSTHUMOUS) 2. IC-56959 LT MANOJ KUMAR PANDEY, 1/11 GR (POSTHUMOUS) 3. 13760533 RFN SANJAY KUMAR, 13 JAK RIF 4. 2690572 GDR YOGENDER SINGH YADAV, 18 GRENADIERS MAHA VIR CHAKRA 1. IC-45952 MAJ SONAM WANGCHUK, LADAKH SCOUTS (IW) 2. IC-51512 MAJ VIVEK GUPTA, 2 RAJ RIF (POSTHUMOUS) 3. IC-52574 MAJ RAJESH SINGH ADHIKARI, 18 GDRS (POSTHUMOUS) 4. IC-55072 MAJ PADMAPANI ACHARYA, 2 RAJ RIF (POSTHUMOUS) 5. IC-57111 CAPT ANUJ NAYYAR, 17 JAT (POSTHUMOUS) 6. IC-58396 CAPT NEIKEZHAKUO KENGURUSE, 2 RAJ RIF (POSTHUMOUS) 7 SS-37111 LT KEISHING CLIFFORD NONGRUM,12 JAK LI(POSTHUMOUS) 8. SS-37691 LT BALWAN SINGH, 18 GRENADIERS 9. 2883178 NK DIGENDRA KUMAR, 2 RAJ RIF VIR CHAKRA 1. IC-35204 COL UMESH SINGH BAWA, 17 JAT 2. IC-37020 COL LALIT RAI, 1/11 GR 3.