Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE for AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (APO)

E-Book - 22. Checklist - Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (A.P.O) By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 22. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 8th May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 27 Nos. Date/Year Details of Issue 1 2 1971 - 1980 1 01/12/1954 International Control Commission - Indo-China 2 15/01/1962 United Nations Force - Congo 3 15/01/1965 United Nations Emergency Force - Gaza 4 15/01/1965 International Control Commission - Indo-China 5 02/10/1968 International Control Commission - Indo-China 6 15.01.1971 Army Day 7 01.04.1971 Air Force Day 8 01.04.1971 Army Educational Corps 9 04.12.1972 Navy Day 10 15.10.1973 The Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers 11 15.10.1973 Zojila Day, 7th Light Cavalary 12 08.12.1973 Army Service Corps 13 28.01.1974 Institution of Military Engineers, Corps of Engineers Day 14 16.05.1974 Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services 15 15.01.1975 Armed Forces School of Nursing 03.11.1976 Winners of PVC-1 : Maj. Somnath Sharma, PVC (1923-1947), 4th Bn. The Kumaon 16 Regiment 17 18.07.1977 Winners of PVC-2: CHM Piru Singh, PVC (1916 - 1948), 6th Bn, The Rajputana Rifles. 18 20.10.1977 Battle Honours of The Madras Sappers Head Quarters Madras Engineer Group & Centre 19 21.11.1977 The Parachute Regiment 20 06.02.1978 Winners of PVC-3: Nk. -

To All the Craft We've Known Before

400,000 Visitors to Mars…and Counting Liftoff! A Fly’s-Eye View “Spacers”Are Doing it for Themselves September/October/November 2003 $4.95 to all the craft we’ve known before... 23rd International Space Development Conference ISDC 2004 “Settling the Space Frontier” Presented by the National Space Society May 27-31, 2004 Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Location: Clarion Meridian Hotel & Convention Center 737 S. Meridian, Oklahoma City, OK 73108 (405) 942-8511 Room rate: $65 + tax, 1-4 people Planned Programming Tracks Include: Spaceport Issues Symposium • Space Education Symposium • “Space 101” Advanced Propulsion & Technology • Space Health & Biology • Commercial Space/Financing Space Space & National Defense • Frontier America & the Space Frontier • Solar System Resources Space Advocacy & Chapter Projects • Space Law and Policy Planned Tours include: Cosmosphere Space Museum, Hutchinson, KS (all day Thursday, May 27), with Max Ary Oklahoma Spaceport, courtesy of Oklahoma Space Industry Development Authority Oklahoma City National Memorial (Murrah Building bombing memorial) Omniplex Museum Complex (includes planetarium, space & science museums) Look for updates on line at www.nss.org or www.nsschapters.org starting in the fall of 2003. detach here ISDC 2004 Advance Registration Form Return this form with your payment to: National Space Society-ISDC 2004, 600 Pennsylvania Ave. S.E., Suite 201, Washington DC 20003 Adults: #______ x $______.___ Seniors/Students: #______ x $______.___ Voluntary contribution to help fund 2004 awards $______.___ Adult rates (one banquet included): $90 by 12/31/03; $125 by 5/1/04; $150 at the door. Seniors(65+)/Students (one banquet included): $80 by 12/31/03; $100 by 5/1/04; $125 at the door. -

Annual Report 2016

BRINGING THE WORLD TO INDIA Annual Report 2016 Observer Research Foundation (ORF) seeks to lead and aid policy thinking towards building a strong and prosperous India in a fair and equitable world. It sees India as a country poised to play a leading role in the knowledge age—a role in which it shall be increasingly called upon to proactively ideate in order to shape global conversations, even as it sets course along its own trajectory of long-term sustainable growth. ORF helps discover and inform India’s choices. It carries Indian voices and ideas to forums shaping global debates. It provides non-partisan, independent, well-researched analyses and inputs to diverse decision-makers in governments, business communities, academia, and to civil society around the world. Our mandate is to conduct in-depth research, provide inclusive platforms and invest in tomorrow’s thought leaders today. Ideas l Forums l Leadership l Impact message from the CHAIRMAN 3 Bharat Goenka message from the DIRECTOR 5 Sunjoy Joshi 9 PROGRAMMES & INITIATIVES 43 FORUMS 51 PUBLICATIONS message from the VICE PRESIDENT 62 Samir Saran Contents 65 FINANCIAL FACTSHEET 68 List of EVENTS 74 List of PUBLICATIONS ANNEX 79 List of FACULTY 67 84 ORF THEMATIC TREE ORF is paying special attention to the intellectual depth of its work and enhancing the ability to deliver products and services efficiently. We are also endeavouring to further extend the reach among the policy makers, academics and business leaders worldwide. —late shri r.k. mishra 1 Message from the Chairman bharat goenka t the end of a journey of over ORF hosted over 240 interactions, a quarter century, even as discussions, roundtables and conferences AI extend my greetings to all on contemporary policy questions. -

समाचार पत्र से चियत अंश Newspapers Clippings

Jan 2021 समाचार पत्र से चियत अंश Newspapers Clippings A Daily service to keep DRDO Fraternity abreast with DRDO Technologies, Defence Technologies, Defence Policies, International Relations and Science & Technology खंड : 46 अंक : 17 23-25 जनवरी 2021 Vol. : 46 Issue : 17 23-25 January 2021 रक्षा िवज्ञान पुतकालय Defence Science Library रक्षा वैरक्षाज्ञािनकिवज्ञानसूचना एवपुतकालयं प्रलेखन क द्र Defence ScientificDefence Information Science & Documentation Library Centre - मेरक्षाटकॉफवैज्ञािनकहाउस,स िदलीूचना एवं 110प्रलेखन 054क द्र Defence ScientificMetcalfe Information House, Delhi & ‐ Documentation110 054 Centre मेटकॉफ हाउस, िदली - 110 054 Metcalfe House, Delhi‐ 110 054 CONTENTS S. No. TITLE Page No. DRDO News 1-17 DRDO Technology News 1-17 1. डीआरडीओ ने �कया �माट� एंट� एयरफ��ड वेपन का सफल उड़ान पर��ण 1 2. Successful flight test of Smart Anti Airfield Weapon 2 3. Visit of Vice Chief of the Air Staff to CAW, DRDO Hyderabad and Air Force 2 Academy 4. वाय ु सेना उप�मुख ने सीएड��य,ू डीआरडीओ हैदराबाद और वाय ु सेना अकादमी का दौरा �कया 3 5. India working on 5th-generation fighter planes: IAF Chief 4 6. DRDO successfully tests smart anti-airfield weapon for 9th time 5 7. भारत ने बनाया एक और खतरनाक और �माट� ह�थयार, द�मनु के हवाई रनवे को पलभर म� कर 6 देगा तबाह 8. Air Marshal HS Arora Param visits DRDO Hyderabad, flies Pilatus PC-7 Trainer 7 Aircraft sortie 9. -

ABBN-Final.Pdf

RESTRICTED CONTENTS SERIAL 1 Page 1. Introduction 1 - 4 2. Sri Lanka Army a. Commands 5 b. Branches and Advisors 5 c. Directorates 6 - 7 d. Divisions 7 e. Brigades 7 f. Training Centres 7 - 8 g. Regiments 8 - 9 h. Static Units and Establishments 9 - 10 i. Appointments 10 - 15 j. Rank Structure - Officers 15 - 16 k. Rank Structure - Other Ranks 16 l. Courses (Local and Foreign) All Arms 16 - 18 m. Course (Local and Foreign) Specified to Arms 18 - 21 SERIAL 2 3. Reference Points a. Provinces 22 b. Districts 22 c. Important Townships 23 - 25 SERIAL 3 4. General Abbreviations 26 - 70 SERIAL 4 5. Sri Lanka Navy a. Commands 71 i RESTRICTED RESTRICTED b. Classes of Ships/ Craft (Units) 71 - 72 c. Training Centres/ Establishments and Bases 72 d. Branches (Officers) 72 e. Branches (Sailors) 73 f. Branch Identification Prefix 73 - 74 g. Rank Structure - Officers 74 h. Rank Structure - Other Ranks 74 SERIAL 5 6. Sri Lanka Air Force a. Commands 75 b. Directorates 75 c. Branches 75 - 76 d. Air Force Bases 76 e. Air Force Stations 76 f. Technical Support Formation Commands 76 g. Logistical and Administrative Support Formation Commands 77 h. Training Formation Commands 77 i. Rank Structure Officers 77 j. Rank Structure Other Ranks 78 SERIAL 6 7. Joint Services a. Commands 79 b. Training 79 ii RESTRICTED RESTRICTED INTRODUCTION USE OF ABBREVIATIONS, ACRONYMS AND INITIALISMS 1. The word abbreviations originated from Latin word “brevis” which means “short”. Abbreviations, acronyms and initialisms are a shortened form of group of letters taken from a word or phrase which helps to reduce time and space. -

Shalyta Magon Army B.Sc, PGDBA(HR) 10 35 54 Sqn Ldr Simran Kaur Bhasin Air Force B.Sc 10 33 56 Maj Anita Marwah Army B.E

Contents About IIMA 2 From the Director's Desk 3 Profile of Faculty Members who taught us 4 From the Course Coordinators 5 What they say about us 6 Batch Profile 8 Placement Preferences 9 Participants Profile Index 10 Resume 12 Course Curriculum 67 Previous Recruiters 68 Placement Coordination 69 1 About IIM-A IIMA has evolved from being India's premier management institute to a notable international school of management in just five decades. It all started with Dr. Vikram Sarabhai and a few spirited industrialists realising that agriculture, education, health, transportation, population control, energy and public administration were vital elements in a growing society, and that it was necessary to efficiently manage these industries. The result was the creation of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad in 1961 as an autonomous body with the active collaboration of the Government of India, Government of Gujarat and the industrial sectors. It was evident that to have a vision was not enough. Effective governance and quality education were seen as critical aspects. From the very start, the founders introduced the concept of faculty governance: all members of the faculty play an important role in administering the diverse academic and non-academic activities of the Institute. The empowerment of the faculty has been the propelling force behind the high quality of learning experience at IIMA. The Institute had initial collaboration with Harvard Business School. This collaboration greatly influenced the Institute's approach to education. Gradually, it emerged as a confluence of the best of Eastern and Western values. 2 From the Director's Desk Dear Recruiter, It gives me immense pleasure and pride to introduce the Tenth batch of Armed Forces Programme (AFP) participants who are undergoing six month residential course in Business Management at IIM Ahmedabad. -

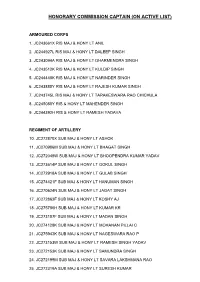

Honorary Commission Captain (On Active List)

HONORARY COMMISSION CAPTAIN (ON ACTIVE LIST) ARMOURED CORPS 1. JC243661X RIS MAJ & HONY LT ANIL 2. JC244927L RIS MAJ & HONY LT DALEEP SINGH 3. JC243094A RIS MAJ & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH 4. JC243512K RIS MAJ & HONY LT KULDIP SINGH 5. JC244448K RIS MAJ & HONY LT NARINDER SINGH 6. JC243880Y RIS MAJ & HONY LT RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 7. JC243745L RIS MAJ & HONY LT TARAKESWARA RAO CHICHULA 8. JC245080Y RIS & HONY LT MAHENDER SINGH 9. JC244392H RIS & HONY LT RAMESH YADAVA REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY 10. JC272870X SUB MAJ & HONY LT ASHOK 11. JC270906M SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHAGAT SINGH 12. JC272049W SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHOOPENDRA KUMAR YADAV 13. JC273614P SUB MAJ & HONY LT GOKUL SINGH 14. JC272918A SUB MAJ & HONY LT GULAB SINGH 15. JC274421F SUB MAJ & HONY LT HANUMAN SINGH 16. JC270624N SUB MAJ & HONY LT JAGAT SINGH 17. JC272863F SUB MAJ & HONY LT KOSHY AJ 18. JC275786H SUB MAJ & HONY LT KUMAR KR 19. JC273107F SUB MAJ & HONY LT MADAN SINGH 20. JC274128K SUB MAJ & HONY LT MOHANAN PILLAI C 21. JC275943K SUB MAJ & HONY LT NAGESWARA RAO P 22. JC273153W SUB MAJ & HONY LT RAMESH SINGH YADAV 23. JC272153K SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAMUNDRA SINGH 24. JC272199M SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAVARA LAKSHMANA RAO 25. JC272319A SUB MAJ & HONY LT SURESH KUMAR 26. JC273919P SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 27. JC271942K SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 28. JC279081N SUB & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH RATHORE 29. JC277689K SUB & HONY LT KAMBALA SREENIVASULU 30. JC277386P SUB & HONY LT PURUSHOTTAM PANDEY 31. JC279539M SUB & HONY LT RAMESH KUMAR SUBUDHI 32. -

Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring

SANDIA REPORT SAND2007-5670 Unlimited Release Printed September 2007 Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring Brigadier (ret.) Asad Hakeem Pakistan Army Brigadier (ret.) Gurmeet Kanwal Indian Army with Michael Vannoni and Gaurav Rajen Sandia National Laboratories Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. -

Anuradhapura Air Base Attack: the Full Story

Anuradhapura Air Base attack: The full story • Attack on Air Base makes mockery of govt's propaganda war • The base had no contingency plan The Sri Lankan Government’s propaganda war which used impressive slogans like ‘liberating the eastern province’, ‘sinking floating warehouses’, ‘restricting the Tigers to the Wanni’ and ‘crushing terrorism outside the north and east’ was made a futile exercise by a team of 21 members of the Black Tiger killer Squad of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and two dual engine light aircrafter that changed the entire situation in one night. Coming out of their hideout the Tiger team carried out a devastating attack on the highly fortified air base of the Sri Lanka Air Force at Anuradhapura early morning on Monday. Embarking on the first such attack in the world by a terrorist organisation, the LTTE launched a ‘Commando Style’ operation against a professional force placing the Government in a very embarrassing situation. During this attack, which resulted in the virtual control for over seven hours of the strategically crucial air base, the Black Tigers destroyed more than 80 percent of the assets of the base’s hanger including a multi-million dollar Beechcraft surveillance aircraft. The Anuradhapura Base acts as one of the main bases in forward operations for military activities in the North. This base is located about four kilometers away from the Sacred City of Anuradhapura on the banks of the scenic ‘Nuwarawewa’. In an environment of peace, the airfield and associated infrastructure at SLAF Anuradhapura plays a significant role in facilitating the passage of air traffic in this region. -

Beyond the Paths of Heaven the Emergence of Space Power Thought

Beyond the Paths of Heaven The Emergence of Space Power Thought A Comprehensive Anthology of Space-Related Master’s Research Produced by the School of Advanced Airpower Studies Edited by Bruce M. DeBlois, Colonel, USAF Professor of Air and Space Technology Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama September 1999 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beyond the paths of heaven : the emergence of space power thought : a comprehensive anthology of space-related master’s research / edited by Bruce M. DeBlois. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Astronautics, Military. 2. Astronautics, Military—United States. 3. Space Warfare. 4. Air University (U.S.). Air Command and Staff College. School of Advanced Airpower Studies- -Dissertations. I. Deblois, Bruce M., 1957- UG1520.B48 1999 99-35729 358’ .8—dc21 CIP ISBN 1-58566-067-1 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii OVERVIEW . ix PART I Space Organization, Doctrine, and Architecture 1 An Aerospace Strategy for an Aerospace Nation . 3 Stephen E. Wright 2 After the Gulf War: Balancing Space Power’s Development . 63 Frank Gallegos 3 Blueprints for the Future: Comparing National Security Space Architectures . 103 Christian C. Daehnick PART II Sanctuary/Survivability Perspectives 4 Safe Heavens: Military Strategy and Space Sanctuary . 185 David W. Ziegler PART III Space Control Perspectives 5 Counterspace Operations for Information Dominance . -

23Rd Indian Infantry Division

21 July 2012 [23 INDIAN INFANTRY DIVISION (1943)] rd 23 Indian Infantry Division (1) st 1 Indian Infantry Brigade (2) 1st Bn. The Seaforth Highlanders (Ross-shire Buffs, The Duke of Albany’s) th th 7 Bn. 14 Punjab Regiment (3) 1st Patiala Infantry (Rajindra Sikhs), Indian State Forces st 1 Bn. The Assam Regiment (4) 37th Indian Infantry Brigade 3rd Bn. 3rd Queen Alexandra’s Own Gurkha Rifles 3rd Bn. 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles (Frontier Force) 3rd Bn. 10th Gurkha Rifles 49th Indian Infantry Brigade 4th Bn. 5th Mahratta Light Infantry 5th (Napiers) Bn. 6th Rajputana Rifles nd th 2 (Berar) Bn. 19 Hyderabad Regiment (5) Divisional Troops The Shere Regiment (6) The Kali Badahur Regiment (6) th 158 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (7) 3rd Indian Field Regiment, Indian Artillery 28th Indian Mountain Regiment, Indian Artillery nd 2 Indian Anti-Tank Regiment, Indian Artillery (8) 68th Field Company, King George V’s Own Bengal Sappers and Miners 71st Field Company, King George V’s Own Bengal Sappers and Miners 91st Field Company, Royal Bombay Sappers and Miners 323rd Field Park Company, Queen Victoria’s Own Madras Sappers and Miners 23rd Indian Divisional Signals, Indian Signal Corps 24th Indian Field Ambulance, Indian Army Medical Corps 47th Indian Field Ambulance, Indian Army Medical Corps 49th Indian Field Ambulance, Indian Army Medical Corps © www.britishmilitaryhistory.co.uk Page 1 21 July 2012 [23 INDIAN INFANTRY DIVISION (1943)] NOTES: 1. The division was formed on 1st January 1942 at Jhansi in India. In March, the embryo formation moved to Ranchi where the majority of the units joined it. -

Ladakh Travels Far and Fast

LADAKH TRAVELS FAR AND FAST Sat Paul Sahni In half a century, Ladakh has transformed itself from the medieval era to as modern a life as any in the mountainous regions of India. Surely, this is an incredible achievement, unprecedented and even unimagin- able in the earlier circumstances of this landlocked trans-Himalayan region of India. In this paper, I will try and encapsulate what has happened in Ladakh since Indian independence in August 1947. Independence and partition When India became independent in 1947, the Ladakh region was cut off not only physically from the rest of India but also in every other field of human activity except religion and culture. There was not even an inch of proper road, although there were bridle paths and trade routes that had been in existence for centuries. Caravans of donkeys, horses, camels and yaks laden with precious goods and commodities had traversed the routes year after year for over two millennia. Thousands of Muslims from Central Asia had passed through to undertake the annual Hajj pilgrimage; and Buddhist lamas and scholars had travelled south to Kashmir and beyond, as well as towards Central Tibet in pursuit of knowledge and religious study and also for pilgrimage. The means of communication were old, slow and outmoded. The postal service was still through runners and there was a single telegraph line operated through Morse signals. There were no telephones, no newspapers, no bus service, no electricity, no hospitals except one Moravian Mission doctor, not many schools, no college and no water taps. In the 1940s, Leh was the entrepôt of this part of the world.