Stravinsky and Jazz: a Comprehensive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manteca”--Dizzy Gillespie Big Band with Chano Pozo (1947) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Raul Fernandez (Guest Post)*

“Manteca”--Dizzy Gillespie Big Band with Chano Pozo (1947) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Raul Fernandez (guest post)* Chano Pozo and Dizzy Gillespie The jazz standard “Manteca” was the product of a collaboration between Charles Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie and Cuban musician, composer and dancer Luciano (Chano) Pozo González. “Manteca” signified one of the beginning steps on the road from Afro-Cuban rhythms to Latin jazz. In the years leading up to 1940, Cuban rhythms and melodies migrated to the United States, while, simultaneously, the sounds of American jazz traveled across the Caribbean. Musicians and audiences acquainted themselves with each other’s musical idioms as they played and danced to rhumba, conga and big-band swing. Anthropologist, dancer and choreographer Katherine Dunham was instrumental in bringing several Cuban drummers who performed in authentic style with her dance troupe in New York in the mid-1940s. All this laid the groundwork for the fusion of jazz and Afro-Cuban music that was to occur in New York City in the 1940s, which brought in a completely new musical form to enthusiastic audiences of all kinds. This coming fusion was “in the air.” A brash young group of artists looking to push jazz in fresh directions began to experiment with a radical new approach. Often playing at speeds beyond the skills of most performers, the new sound, “bebop,” became the proving ground for young New York jazz musicians. One of them, “Dizzy” Gillespie, was destined to become a major force in the development of Afro-Cuban or Latin jazz. Gillespie was interested in the complex rhythms played by Cuban orchestras in New York, in particular the hot dance mixture of jazz with Afro-Cuban sounds presented in the early 1940s by Mario Bauzá and Machito’s Afrocubans Orchestra which included singer Graciela’s balmy ballads. -

The Connection Between Jazz and Drug Abuse: a Comparative Look at the Effects of Widespread Narcotics Abuse on Jazz Music in the 40’S, 50’S, and 60’S

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship Musicology and Ethnomusicology 11-2019 The Connection Between Jazz and Drug Abuse: A Comparative Look at the Effects of Widespread Narcotics Abuse on Jazz Music in the 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s Aaron Olson University of Denver, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Olson, Aaron, "The Connection Between Jazz and Drug Abuse: A Comparative Look at the Effects of Widespread Narcotics Abuse on Jazz Music in the 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s" (2019). Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship. 52. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/52 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Musicology and Ethnomusicology at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. The Connection Between Jazz and Drug Abuse: A Comparative Look at the Effects of Widespread Narcotics Abuse on Jazz Music in the 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s This bibliography is available at Digital Commons @ DU: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/52 The Connection between Jazz and Drug Abuse: A Comparative Look at the Effects of Widespread Narcotics Abuse on Jazz Music in the 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s. An Annotated Bibliography By: Aaron Olson November, 2019 From the 1940s to the 1960s drug abuse in the jazz community was almost at epidemic proportions. -

Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky's Ballets. New Haven: Yale University

Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky’s Ballets. New Haven: Yale University Press. Reviewed by Maeve Sterbenz Charles M. Joseph’s recent monograph explores an important subset of Stravinsky’s complete oeuvre, namely his works for dance. One of the aims of the book is to stress the importance of dance for Stravinsky throughout his career as a source of inspiration that at times significantly shaped his develop- ment as a composer. Joseph offers richly contextualized and detailed pictures of Stravinsky’s ballets, ones that will be extremely useful for both dance and music scholars. While he isolates each work, several themes run through Joseph’s text. Among the most important are Stravinsky’s self–positioning as simultaneously Russian and cosmopolitan; and Stravinsky’s successes in collaboration, through which he was able to create fully integrated ballets that elevated music’s traditionally subservient role in relation to choreography. To begin, Joseph introduces his motivation for the project, arguing for the necessity of an in–depth study of Stravinsky’s works for dance in light of the fact that they comprise a significant fraction of the composer’s output (more so than any other Western classical composer) and that these works, most notably The Rite of Spring, occupy such a prominent place in the Western canon. According to Joseph, owing to Stravinsky’s sensitivity to the “complexly subtle counterpoint between ballet’s interlocking elements” (xv), the ballets stand out in the genre for their highly interdisciplinary nature. In the chapters that follow, Joseph examines each of the ballets, focusing alternately on details of the works, histories of their production and reception, and their biographical contexts. -

JEWS and JAZZ (Lorry Black and Jeff Janeczko)

UNIT 8 JEWS, JAZZ, AND JEWISH JAZZ PART 1: JEWS AND JAZZ (Lorry Black and Jeff Janeczko) A PROGRAM OF THE LOWELL MILKEN FUND FOR AMERICAN JEWISH MUSIC AT THE UCLA HERB ALPERT SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIT 8: JEWS, JAZZ, AND JEWISH JAZZ, PART 1 1 Since the emergence of jazz in the late 19th century, Jews have helped shape the art form as musicians, bandleaders, songwriters, promoters, record label managers and more. Working alongside African Americans but often with fewer barriers to success, Jews helped jazz gain recognition as a uniquely American art form, symbolic of the melting pot’s potential and a pluralistic society. At the same time that Jews helped establish jazz as America’s art form, they also used it to shape the contours of American Jewish identity. Elements of jazz infiltrated some of America’s earliest secular Jewish music, formed the basis of numerous sacred works, and continue to influence the soundtrack of American Jewish life. As such, jazz has been an important site in which Jews have helped define what it means to be American, as well as Jewish. Enduring Understandings • Jazz has been an important platform through which Jews have helped shape the pluralistic nature of American society, as well as one that has shaped understandings of American Jewish identity. • Jews have played many different roles in the development of jazz, from composers to club owners. • Though Jews have been involved in jazz through virtually all phases of its development, they have only used it to express Jewishness in a relatively small number of circumstances. -

Jazz Arts Program Student 2019-2020

JAZZ ARTS PROGRAM STUDENT 2019-2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome/Introduction 3 Applied Lessons 4 Your Teacher 4 Change of Teacher 4 Dividing Lessons Between Two Teachers 4 Professional Leave 5 Attendance Policy 5 Playing-related Pain 5 Ensemble and Audition Requirements 6 Juries 7 Jury for Non-graduating Students 7 Advanced Standing Jury 7 Jury Requirements for Performance Majors 8 Jury Requirements for Composition Majors 9 Comments 9 Grading 9 Postponement 9 Recitals 10 Scheduling Recitals 10 Non-required Recitals 10 Required Recitals - Undergraduate and Graduate 10 Recording of Recitals 11 Department Policies 12 Attendance 12 Subs 12 Attire 12 Grading System 13 Equipment 13 Jazz Arts Program Communications: E-mail, 13 Student Website Faculty/Student Conferences 14 Contacting the Jazz Arts Program Staff 14 Repertoire Lists 15 2 WELCOME/INTRODUCTION Dear Students, Welcome to the MSM family! We are a community of artists, educators and dreamers located in the thriving mecca and birthplace of modern jazz, Harlem, NY. This is the beginning of a journey that will undoubtedly have a major impact on the rest of your lives. As a former student, I spent the most important and transformative years of my artistic life at MSM. It was during my time here that I acquired the musical skills necessary to articulate my story in organized sound. The success of our MSM family is predicated upon three fundamental core values: Love ( empathy), Trust and Respect Jazz is an art form born from a desire to authentically express one’s individuality. Inherent in its construct is a deep understanding and appreciation for the value of an inclusive culture rich in diverse perspectives. -

Elements of Traditional Folk Music and Serialism in the Piano Music of Cornel Țăranu

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music Music, School of 12-2013 ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU Cristina Vlad University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Commons Vlad, Cristina, "ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU" (2013). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 65. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU by Cristina Ana Vlad A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Mark Clinton Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2013 ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU Cristina Ana Vlad, DMA University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Mark Clinton The socio-political environment in the aftermath of World War II has greatly influenced Romanian music. During the Communist era, the government imposed regulations on musical composition dictating that music should be accessible to all members of society. -

22 by Gretchen Horlacher a Fundamental Issue in the Analysis Of

Sketches and Superimposition in Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms by Gretchen Horlacher A fundamental issue in the analysis of Stravinsky’s music is to describe how the composer juxtaposes and superimposes repeating motivic fragments. Do layered ostinati spin out in opposition to one another or do they interact? Does the progress of one affect the progress of another? Do they create for- mal relationships beyond their own repetitions? Evidence in sketches for works spanning the Russian period through the early serial work Agon (1953–57) suggests that this issue was a primary concern for the composer: many sketches and drafts are dedicated to working out the relationships be- tween and among simultaneously sounding strata so that they jointly shape passages of music. These documents share a common working method. Early in the composi- tional process, Stravinsky seems often to have drafted short “phrases” where the constituent motivic fragments are placed in relationship but repeated only briefly or not at all; subsequent drafts expand the lengths of phrases by in- serting repetitions of existing material into the original phrases.1 Such a pro- cedure allows us to compare the longer (and most often retained) versions with their shorter predecessors, giving us insight both into how Stravinsky develops his material and what might constitute a complete formal unit. In other words, we can trace the expansions of phrases through interpolation in order to identify how later versions have a more continuous formal shape and fit more easily into larger formal units. Consider as an example two sketches for a passage from the third move- ment of the Symphony of Psalms (1929–30); the two sketches are reproduced as Examples 1a and 1b and the final score is reproduced as Example 2.2 A pre- liminary description of the passage might go as follows. -

The Curtis Institute of Music Roberto Díaz, President

The Curtis Institute of Music Roberto Díaz, President This concert will be available online for free streaming 2008–09 Student Recital Series and download on Thursday, February 19. The Edith L. and Robert Prostkoff Memorial Concert Series Visit www.instantencore.com/curtis after 12 noon and enter this download code in the upper-right corner of the webpage: Feb09CTour Forty-Fourth Student Recital: Curtis On Tour Click “Go” and follow the instructions on the screen to save music Wednesday, February 18 at 8 p.m. Field Concert Hall onto your computer. Divertimento for Violin and Piano Igor Stravinsky Next Student Recital Sinfonia (1882–1971) Friday, February 20 at 8 p.m. Danses suisses 20/21: The Curtis Contemporary Music Ensemble— Scherzo Second Viennese School, Program III Pas de deux: Adagio—Variation—Coda Field Concert Hall Josef Špaček, violin Kuok-man Lio, piano Berg Sieben frühe Lieder Amanda Majeski, soprano Three Pieces for Clarinet Solo Stravinsky Mikael Eliasen, piano Yao Guang Zhai, clarinet String Quartet, Op. 3 From the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám David Ludwig Joel Link, violin (world premiere) (b. 1972) Bryan A. Lee, violin Secrets of Creation Milena Pajaro-van de Stadt, viola Turning of Time Camden Shaw, cello Labor of Life Floating Particles Schoenberg Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15 Carpe Diem Charlotte Dobbs, soprano Allison Sanders, mezzo-soprano David Moody, piano Yao Guang Zhai, clarinet William Short, bassoon Phantasy, Op. 47 Christopher Stingle, trumpet Elizabeth Fayette, violin Ryan Seay, trombone Pallavi Mahidhara, piano Benjamin Folk, percussion Josef Špaček, violin Programs are subject to change. Harold Hall Robinson, double bass Call the Recital Hotline, 215-893-5261, for the most up-to-date information. -

David Justin CV 2014 Pennsylvania Ballet

David Justin 4603 Charles Ave Austin TX 787846 Tel: 512-576-2609 Email: [email protected] Web site: http://www.davidjustin.net CURRICULUM VITAE ACADEMIC EDUCATION • University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, Master of Arts in Dance in Education and the Community, May 2000. Thesis: Exploring the collaboration of imagination, creativity, technique and people across art forms, Advisor: Tansin Benn • Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, Edward Kemp, Artistic Director, London, United Kingdom, 2003. Certificate, 285 hours training, ‘Acting Shakespeare.’ • International Dance Course for Professional Choreographers and Composers, Robert Cohen, Director, Bretton College, United Kingdom, 1996, full scholarship DANCE EDUCATION • School of American Ballet, 1987, full scholarship • San Francisco Ballet School, 1986, full scholarship • Ballet West Summer Program, 1985, full scholarship • Dallas Metropolitan Ballet School, 1975 – 1985, full scholarship PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Choreographer, 1991 to present See full list of choreographic works beginning on page 6. Artistic Director, American Repertory Ensemble, Founder and Artistic Director, 2005 to present $125,000 annual budget, 21 contract employees, 9 board members11 principal dancers from the major companies in the US, 7 chamber musicians, 16 performances a year. McCullough Theater, Austin, TX; Florence Gould Hall, New York, NY; Demarco Roxy Art House, Edinburgh, Scotland; Montenegrin National Theatre, Podgorica, Montenegro; Miller Outdoor Theatre, Houston, TX, Long Center for the Performing Arts, -

A Symphonic Psalm, After a Drama by René Morax King David

ELLIOT JONES MUSIC DIRECTOR A Symphonic Psalm, after a drama by René Morax Music by Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) Please silence all cellular phones and other electronic devices King David PART I 1. Introduction (Orchestra & Narrator) 2. The song of David, the shepherd: God shall be my shepherd kind. 3. Psalm: All praise to him, the Lord of glory, the everlasting God my helper. 4. Fanfare and entry of Goliath 5. Song of victory: David is great, the Philistines overthrown. Chosen of God is he. 6. Psalm: In the Lord I put my faith, I put my trust. 7. Psalm: O had I wings like a dove, then I would fly away and be at rest. 8. Song of the prophets: Man that is born of a woman lives but a little while. 9. Psalm: Pity me Lord, for I am weak. 10. Saul’s camp 11. Psalm: God, the Lord shall be my light and my salvation. What cause have I to fear? 12. Incantation of the Witch of Endor 13. March of the Philistines 14. The lament of Gilboa: Ah! Weep for Saul. 1 PART II ORCHESTRA 15. Song of the daughters of Israel: Sister, oh sing thy song! Never has God forsaken us. 16. The dance before the ark: Mighty God be with us, O splendor of the morn. FLUTE and PICCOLO CELLO Alexander Lipay, Paula Redinger Anne Gratz INTERMISSION OBOE and ENGLISH HORN BASS PART III Marquise Demaree Dylan DeRobertis 17. Song: Now my voice in song up-soaring shall loud proclaim my king afar. 18. -

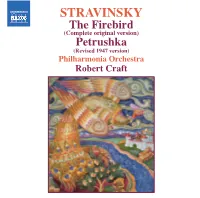

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise. -

Roman Vlad's Reception of Stravinsky

Hermeneutics and Creative Process: Roman Vlad’s Reception of Stravinsky Susanna Pasticci Università degli Studi di Cassino e del Lazio meridionale Roman Vlad’s experience of music was a complex universe, which manifested itself in various forms.1 His research on musical composition went hand in hand with an extraordinary intellectual activity, which resulted in the publication of several studies on the theory and history of music, and a constant activity as a promoter and critic of music. Vlad was capable of switching with great nonchalance from the role of the composer interested in new experimental forms to that of a scholar working with great methodological rigour on the music of the past and of the present. It was inevitable that these two activities would have an impact on his interpretation of music. In an effort to illustrate the complexity of this dialectic, the present article focuses on Vlad’s reception of Stravinsky’s work, analysing in parallel Vlad’s essays on Stravinsky published in the 1950s and his musical compositions written in the same period. In his writings, Vlad repeatedly underlines the centrality of the sacred in Stravinsky’s work, a rather original interpretation, which is unique in the critical debate of the time. During those same years, the sacred acquired great importance also in his musical compositions, a fact that already evidences the close relation between Vlad’s interpretation of Stravinsky’s work and his own 41 ARCHIVAL NOTES Sources and Research from the Institute of Music, No. 2 (2017) © Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venezia ISSN 2499–832X | ISBN 9788896445167 SUSANNA PASTICCI creative activity.