Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky's Ballets. New Haven: Yale University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 355 H-France Review Vol. 9 (June 2009), No. 86 Peter Read, Picasso and Apollinaire

H-France Review Volume 9 (2009) Page 355 H-France Review Vol. 9 (June 2009), No. 86 Peter Read, Picasso and Apollinaire: The Persistence of Memory (Ahmanson-Murphy Fine Arts Books). University of California Press: Berkeley, 2008. 334 pp. + illustrations. $49.95 (hb). ISBN 052-0243- 617. Review by John Finlay, Independent Scholar. Peter Read’s Picasso et Apollinaire: Métamorphoses de la memoire 1905/1973 was first published in France in 1995 and is now translated into English, revised, updated and developed incorporating the author’s most recent publications on both Picasso and Apollinaire. Picasso & Apollinaire: The Persistence of Memory also uses indispensable material drawn from pioneering studies on Picasso’s sculptures, sketchbooks and recent publications by eminent scholars such as Elizabeth Cowling, Anne Baldassari, Michael Fitzgerald, Christina Lichtenstern, William Rubin, John Richardson and Werner Spies as well as a number of other seminal texts for both art historian and student.[1] Although much of Apollinaire’s poetic and literary work has now been published in French it remains largely untranslated, and Read’s scholarly deciphering using the original texts is astonishing, daring and enlightening to the Picasso scholar and reader of the French language.[2] Divided into three parts and progressing chronologically through Picasso’s art and friendship with Apollinaire, the first section astutely analyses the early years from first encounters, Picasso’s portraits of Apollinaire, shared literary and artistic interests, the birth of Cubism, the poet’s writings on the artist, sketches, poems and “primitive art,” World War I, through to the final months before Apollinaire’s death from influenza on 9 November 1918. -

22 by Gretchen Horlacher a Fundamental Issue in the Analysis Of

Sketches and Superimposition in Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms by Gretchen Horlacher A fundamental issue in the analysis of Stravinsky’s music is to describe how the composer juxtaposes and superimposes repeating motivic fragments. Do layered ostinati spin out in opposition to one another or do they interact? Does the progress of one affect the progress of another? Do they create for- mal relationships beyond their own repetitions? Evidence in sketches for works spanning the Russian period through the early serial work Agon (1953–57) suggests that this issue was a primary concern for the composer: many sketches and drafts are dedicated to working out the relationships be- tween and among simultaneously sounding strata so that they jointly shape passages of music. These documents share a common working method. Early in the composi- tional process, Stravinsky seems often to have drafted short “phrases” where the constituent motivic fragments are placed in relationship but repeated only briefly or not at all; subsequent drafts expand the lengths of phrases by in- serting repetitions of existing material into the original phrases.1 Such a pro- cedure allows us to compare the longer (and most often retained) versions with their shorter predecessors, giving us insight both into how Stravinsky develops his material and what might constitute a complete formal unit. In other words, we can trace the expansions of phrases through interpolation in order to identify how later versions have a more continuous formal shape and fit more easily into larger formal units. Consider as an example two sketches for a passage from the third move- ment of the Symphony of Psalms (1929–30); the two sketches are reproduced as Examples 1a and 1b and the final score is reproduced as Example 2.2 A pre- liminary description of the passage might go as follows. -

PICASSO Les Livres D’Artiste E T Tis R a D’ S Vre Li S Le PICASSO

PICASSO LES LIVRES d’ARTISTE The collection of Mr. A*** collection ofThe Mr. d’artiste livres Les PICASSO PICASSO Les livres d’artiste The collection of Mr. A*** Author’s note Years ago, at the University of Washington, I had the opportunity to teach a class on the ”Late Picasso.” For a specialist in nineteenth-century art, this was a particularly exciting and daunting opportunity, and one that would prove formative to my thinking about art’s history. Picasso does not allow for temporalization the way many other artists do: his late works harken back to old masterpieces just as his early works are themselves masterpieces before their time, and the many years of his long career comprise a host of “periods” overlapping and quoting one another in a form of historico-cubist play that is particularly Picassian itself. Picasso’s ability to engage the art-historical canon in new and complex ways was in no small part influenced by his collaborative projects. It is thus with great joy that I return to the varied treasures that constitute the artist’s immense creative output, this time from the perspective of his livres d’artiste, works singularly able to point up his transcendence across time, media, and culture. It is a joy and a privilege to be able to work with such an incredible collection, and I am very grateful to Mr. A***, and to Umberto Pregliasco and Filippo Rotundo for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating project. The writing of this catalogue is indebted to the work of Sebastian Goeppert, Herma Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer, whose Pablo Picasso. -

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism" Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)! Biographical sketch:! §" Born in St. Petersburg, Russia.! §" Studied composition with “Mighty Russian Five” composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov.! §" Emigrated to Switzerland (1910) and France (1920) before settling in the United States during WW II (1939). ! §" Along with Arnold Schönberg, generally considered the most important composer of the first half or the 20th century.! §" Works generally divided into three style periods:! •" “Russian” Period (c.1907-1918), including “primitivist” works! •" Neoclassical Period (c.1922-1952)! •" Serialist Period (c.1952-1971)! §" Died in New York City in 1971.! Pablo Picasso: Portrait of Igor Stravinsky (1920)! Ballets Russes" History:! §" Founded in 1909 by impresario Serge Diaghilev.! §" The original company was active until Diaghilev’s death in 1929.! §" In addition to choreographing works by established composers (Tschaikowsky, Rimsky- Korsakov, Borodin, Schumann), commissioned important new works by Debussy, Satie, Ravel, Prokofiev, Poulenc, and Stravinsky.! §" Stravinsky composed three of his most famous and important works for the Ballets Russes: L’Oiseau de Feu (Firebird, 1910), Petrouchka (1911), and Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913).! §" Flamboyant dancer/choreographer Vaclav Nijinsky was an important collaborator during the early years of the troupe.! ! Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929) ! Ballets Russes" Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky.! Stravinsky with Vaclav Nijinsky as Petrouchka (Paris, 1911).! Ballets -

A Level Schools Concert November 2014

A level Schools Concert November 2014 An Exploration of Neoclassicism Teachers’ Resource Pack Autumn 2014 2 London Philharmonic Orchestra A level Resources Unauthorised copying of any part of this teachers’ pack is strictly prohibited The copyright of the project pack text is held by: Rachel Leach © 2014 London Philharmonic Orchestra ©2014 Any other copyrights are held by their respective owners. This pack was produced by: London Philharmonic Orchestra Education and Community Department 89 Albert Embankment London SE1 7TP Rachel Leach is a composer, workshop leader and presenter, who has composed and worked for many of the UK’s orchestras and opera companies, including the London Sinfonietta, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Wigmore Hall, Glyndebourne Opera, English National Opera, Opera North, and the London Symphony Orchestra. She studied at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, at Opera Lab and Dartington. Recent commissions include ‘Dope Under Thorncombe’ for Trilith Films and ‘In the belly of a horse’, a children’s opera for English Touring Opera. Rachel’s music has been recorded by NMC and published by Faber. Her community opera ‘One Day, Two Dawns’ written for ETO recently won the RPS award for best education project 2009. As well as creative music-making and composition in the classroom, Rachel is proud to be the lead tutor on the LSO's teacher training scheme for over 8 years she has helped to train 100 teachers across East London. Rachel also works with Turtle Key Arts and ETO writing song cycles with people with dementia and Alzheimer's, an initiative which also trains students from the RCM, and alongside all this, she is increasingly in demand as a concert presenter. -

STRAVINSKY's NEO-CLASSICISM and HIS WRITING for the VIOLIN in SUITE ITALIENNE and DUO CONCERTANT by ©2016 Olivia Needham Subm

STRAVINSKY’S NEO-CLASSICISM AND HIS WRITING FOR THE VIOLIN IN SUITE ITALIENNE AND DUO CONCERTANT By ©2016 Olivia Needham Submitted to the graduate degree program in School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________________ Chairperson: Paul Laird ________________________________________ Véronique Mathieu ________________________________________ Bryan Haaheim ________________________________________ Philip Kramp ________________________________________ Jerel Hilding Date Defended: 04/15/2016 The Dissertation Committee for Olivia Needham certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: STRAVINSKY’S NEO-CLASSICISM AND HIS WRITING FOR THE VIOLIN IN SUITE ITALIENNE AND DUO CONCERTANT ________________________________________ Chairperson: Paul Laird Date Approved: 04/15/2016 ii ABSTRACT This document is about Stravinsky and his violin writing during his neoclassical period, 1920-1951. Stravinsky is one of the most important neo-classical composers of the twentieth century. The purpose of this document is to examine how Stravinsky upholds his neoclassical aesthetic in his violin writing through his two pieces, Suite italienne and Duo Concertant. In these works, Stravinsky’s use of neoclassicism is revealed in two opposite ways. In Suite Italienne, Stravinsky based the composition upon actual music from the eighteenth century. In Duo Concertant, Stravinsky followed the stylistic features of the eighteenth century without parodying actual music from that era. Important types of violin writing are described in these two works by Stravinsky, which are then compared with examples of eighteenth-century violin writing. iii Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was born in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov) in Russia near St. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

Influence of Commedia Dell‟Arte on Stravinsky‟S Suite Italienne D.M.A

Influence of Commedia dell‟Arte on Stravinsky‟s Suite Italienne D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sachiho Cynthia Murasugi, B.M., M.A., M.B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Kia-Hui Tan, Advisor Paul Robinson Mark Rudoff Copyright by Sachiho Cynthia Murasugi 2009 Abstract Suite Italienne for violin and piano (1934) by Stravinsky is a compelling and dynamic work that is heard in recitals and on recordings. It is based on Stravinsky‟s music for Pulcinella (1920), a ballet named after a 16th century Neapolitan stock character. The purpose of this document is to examine, through the discussion of the history and characteristics of Commedia dell‟Arte ways in which this theatre genre influenced Stravinsky‟s choice of music and compositional techniques when writing Pulcinella and Suite Italienne. In conclusion the document proposes ways in which the violinist can incorporate the elements of Commedia dell‟Arte that Stravinsky utilizes in order to give a convincing and stylistic performance. ii Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Kia-Hui Tan and my committee members, Dr. Paul Robinson, Prof. Mark Rudoff, and Dr. Jon Woods. I also would like to acknowledge the generous assistance of my first advisor, the late Prof. Michael Davis. iii Vita 1986………………………………………….B.M., Manhattan School of Music 1988-1989……………………………….…..Visiting International Student, Utrecht Conservatorium 1994………………………………………….M.A., CUNY, Queens College 1994-1995……………………………………NEA Rural Residency Grant 1995-1996……………………………………Section violin, Louisiana Philharmonic 1998………………………………………….M.B.A., Tulane University 1998-2008……………………………………Part-time instructor, freelance violinist 2001………………………………………….Nebraska Arts Council Touring Artists Roster 2008 to present………………………………Lecturer in Music, Salisbury University Publications “Stravinsky‟s Suite Italienne Unmasked.” Stringendo 25.4 (2009):19. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

Burkholder/Grout/Palisca, Eighth Edition, Chapter 32 30 Chapter 32

30 11. SR: After WW I he founded/directed the __________. Between 19__ and 19__ the society gave approximately Chapter 32 ___ performances. He started the twelve-tone method in Modernism and the Classical Tradition 19__. His wife died and a year later he married ______. (He fathered __ children.) The Nazis came into power in 1. (810) What are the criteria established by the classics? 19__. Although Schoenberg had converted to _____, he converted back. From 19__, he taught at _____. He was forced to retire in 1944 because ________. He died on July __, 1951, a triskaidekaphobiac. 2. Modernists sought to challenge our ______ and _____. 12. SR: Make a list of his major works: 3. (811) Were they opposed to the classics? 4. What is the paradox of modern classical music? 5. All six composers in this chapter "began writing ____ music in the late _____ styles, but then found their own voice. 13. (813) SR: What's his position in the first paragraph? 6. What is the meaning of atonality? 14. SR: What's the essence of the second paragraph? 7. What is the twelve-tone method? 15. "The principle of _____ helps explain how Schoenberg's 8. Name the three works in the first paragraph of "Tonal music would evolve." Works" and name the influential composer. 16. (815) Explain "the emancipation of dissonance." 9. What compositional technique did he employ in his first 17. What were the three elements of Schoenberg's musical string quartet, Op. 7, D minor? What is the structure? organization? 10. -

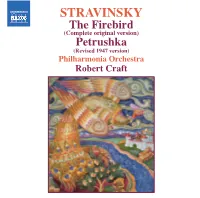

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise. -

World Premiere of Orpheus Alive with Company Premiere of Chaconne Opens November 15 Principal Casting Announced

World Premiere of Orpheus Alive with Company Premiere of Chaconne Opens November 15 Principal Casting Announced November 4, 2019 … Karen Kain, Artistic Director of The National Ballet of Canada, today announced the principal casting for the world premiere of Orpheus Alive by Choreographic Associate Robert Binet featuring a new commissioned score by acclaimed New York composer Missy Mazzoli. Orpheus Alive is paired with the company premiere of George Balanchine’s Chaconne November 15 – 21, 2019 at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts. #OrpheusAliveNBC #ChaconneNBC Artists have long been fascinated with the Greek myth of Orpheus, the gifted musician who rescues his lover Eurydice from death only to lose her again in a moment of doubt. At its core, theirs is a story about love, trust and the redemptive potential of art. With Orpheus Alive, Mr. Binet brings a fresh perspective to the myth, casting Orpheus as a woman, Eurydice as a man and the audience as gods of the underworld who decide their fate. The opening night cast on November 15 will feature First Soloist Jenna Savella and Second Soloist Spencer Hack as Orpheus and Eurydice along with Principal Dancer Sonia Rodriguez as Eurydice’s Mother. Subsequent performances will feature Principal Dancer Heather Ogden and First Soloist Hannah Fischer in the role of Orpheus, Principal Dancers Harrison James and Brendan Saye as Eurydice and First Soloist Tanya Howard as Eurydice’s Mother. In the music for Orpheus Alive, Ms. Mazzoli quotes Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice, setting the tone for George Balanchine’s Chaconne which features the same Gluck score.