NOTES on the MUSIC by Robert M. Johnstone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång Till

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång till Lotta, Jan Sandström. Edition Tarrodi: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991. Trombone and piano. Requires modest range (F – g flat1), well-developed lyricism, and musicianship. There are two versions of this piece, this and another that is scored a minor third higher. Written dynamics are minimal. Although phrases and slurs are not indicated, it is a SONG…encourage legato tonguing! Stephan Schulz, bass trombonist of the Berlin Philharmonic, gives a great performance of this work on YouTube - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mn8569oTBg8. A Winter’s Night, Kevin McKee, 2011. Available from the composer, www.kevinmckeemusic.com. Trombone and piano. Explores the relative minor of three keys, easy rhythms, keys, range (A – g1, ossia to b flat1). There is a fine recording of this work on his web site. Trombone Sonata, Gordon Jacob. Emerson Edition: Yorkshire, England, 1979. Trombone and piano. There are no real difficult rhythms or technical considerations in this work, which lasts about 7 minutes. There is tenor clef used throughout the second movement, and it switches between bass and tenor in the last movement. Range is F – b flat1. Recorded by Dr. Ron Babcock on his CD Trombone Treasures, and available at Hickey’s Music, www.hickeys.com. Divertimento, Edward Gregson. Chappell Music: London, 1968. Trombone and piano. Three movements, range is modest (G-g#1, ossia a1), bass clef throughout. Some mixed meter. Requires a mute, glissandi, and ad. lib. flutter tonguing. Recorded by Brett Baker on his CD The World of Trombone, volume 1, and can be purchased at http://www.brettbaker.co.uk/downloads/product=download-world-of-the- trombone-volume-1-brett-baker. -

Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky's Ballets. New Haven: Yale University

Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky’s Ballets. New Haven: Yale University Press. Reviewed by Maeve Sterbenz Charles M. Joseph’s recent monograph explores an important subset of Stravinsky’s complete oeuvre, namely his works for dance. One of the aims of the book is to stress the importance of dance for Stravinsky throughout his career as a source of inspiration that at times significantly shaped his develop- ment as a composer. Joseph offers richly contextualized and detailed pictures of Stravinsky’s ballets, ones that will be extremely useful for both dance and music scholars. While he isolates each work, several themes run through Joseph’s text. Among the most important are Stravinsky’s self–positioning as simultaneously Russian and cosmopolitan; and Stravinsky’s successes in collaboration, through which he was able to create fully integrated ballets that elevated music’s traditionally subservient role in relation to choreography. To begin, Joseph introduces his motivation for the project, arguing for the necessity of an in–depth study of Stravinsky’s works for dance in light of the fact that they comprise a significant fraction of the composer’s output (more so than any other Western classical composer) and that these works, most notably The Rite of Spring, occupy such a prominent place in the Western canon. According to Joseph, owing to Stravinsky’s sensitivity to the “complexly subtle counterpoint between ballet’s interlocking elements” (xv), the ballets stand out in the genre for their highly interdisciplinary nature. In the chapters that follow, Joseph examines each of the ballets, focusing alternately on details of the works, histories of their production and reception, and their biographical contexts. -

A Level Schools Concert November 2014

A level Schools Concert November 2014 An Exploration of Neoclassicism Teachers’ Resource Pack Autumn 2014 2 London Philharmonic Orchestra A level Resources Unauthorised copying of any part of this teachers’ pack is strictly prohibited The copyright of the project pack text is held by: Rachel Leach © 2014 London Philharmonic Orchestra ©2014 Any other copyrights are held by their respective owners. This pack was produced by: London Philharmonic Orchestra Education and Community Department 89 Albert Embankment London SE1 7TP Rachel Leach is a composer, workshop leader and presenter, who has composed and worked for many of the UK’s orchestras and opera companies, including the London Sinfonietta, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Wigmore Hall, Glyndebourne Opera, English National Opera, Opera North, and the London Symphony Orchestra. She studied at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, at Opera Lab and Dartington. Recent commissions include ‘Dope Under Thorncombe’ for Trilith Films and ‘In the belly of a horse’, a children’s opera for English Touring Opera. Rachel’s music has been recorded by NMC and published by Faber. Her community opera ‘One Day, Two Dawns’ written for ETO recently won the RPS award for best education project 2009. As well as creative music-making and composition in the classroom, Rachel is proud to be the lead tutor on the LSO's teacher training scheme for over 8 years she has helped to train 100 teachers across East London. Rachel also works with Turtle Key Arts and ETO writing song cycles with people with dementia and Alzheimer's, an initiative which also trains students from the RCM, and alongside all this, she is increasingly in demand as a concert presenter. -

Wind Ensemble Repertoire

UNCG Wind Ensemble Programming April 29, 2009 Variations on "America" ‐ Charles Ives, arr. William Schuman and William Rhoads Symphonic Dances from West Side Story Leonard Bernstein, arr. Paul Lavender Mark Norman, guest conductor Children's March: "Over the Hills and Far Away” Percy Grainger Kiyoshi Carter, guest conductor American Guernica Adolphus Hailstork Andrea Brown, guest conductor Las Vegas Raga Machine Alejandro Rutty, World Premiere March from Symphonic Metamorphosis Paul Hindemith, arr. Keith Wilson March 27, 2009 at College Band Directors National Association National Conference, Bates Recital Hall, University of Texas at Austin Fireworks, Opus 8 Igor Stravinsky, trans. Mark Rogers It perched for Vespers nine Joel Puckett Theme and Variations, Opus 43a Arnold Schoenberg Shadow Dance David Dzubay Commissioned by UNCG Wind Ensemble Four Factories Carter Pann Commissioned by UNCG Wind Ensemble FuniculiFunicula Rhapsody Luigi Denza, arr. Yo Goto February 20, 2009 Fireworks, Op. 4 Igor Stravinsky, trans. Mark Rogers O Magnum Mysterium Morten Lauridsen H. Robert Reynolds, guest conductor Theme and Variations, Op. 43a ‐ Arnold Schoenberg Symphony No. 2 Frank Ticheli Frank Ticheli, guest conductor December 3, 2008 Raise the Roof ‐ Michael Daugherty John R. Beck, timpani soloist Intermezzo Monte Tubb Andrea Brown, guest conductor Shadow Dance David Dzubay Four Factories Carter Pann FuniculiFunicula Rhapsody Luigi Denza, arr. Yo Goto October 8, 2008 Fireworks, Opus 8 ‐ Igor Stravinsky, trans. Mark Rogers it perched for Vespers nine Joel Puckett Theme and Variations, Op. 43a Arnold Schoenberg Fantasia in G J.S. Bach, arr. R. F. Goldman Equus ‐ Eric Whitacre Andrea Brown, guest conductor Entry March of the Boyars Johan Halvorsen Fanfare Ritmico ‐ Jennifer Higdon May 4, 2008 Early Light Carolyn Bremer Icarus and Daedalus ‐ Keith Gates Emblems Aaron Copland Aegean Festival Overture Andreas Makris Mark A. -

Beyond the Machine Photo by Claudio Papapietro

Beyond The Machine Photo by Claudio Papapietro Juilliard Scholarship Fund The Juilliard School is the vibrant home to more than 800 dancers, actors, and musicians, over 90 percent of whom are eligible for financial aid. With your help, we can offer the scholarship support that makes a world of difference—to them and to the global future of dance, drama, and music. Behind every Juilliard artist is all of Juilliard—including you. For more information please contact Tori Brand at (212) 799-5000, ext. 692, or [email protected]. Give online at giving.juilliard.edu/scholarship. The Juilliard School presents Center for Innovation in the Arts Edward Bilous, Founding Director Beyond the Machine 19.1 InterArts Workshop March 26 and 27, 2019, 7:30pm (Juilliard community only) March 28, 2019, 7pm Conversation with the artists, hosted by William F. Baker 7:30pm Performance Rosemary and Meredith Willson Theater The Man Who Loved the World Treyden Chiaravalloti, Director Eric Swanson, Actor John-Henry Crawford, Composer On film: Jared Brown, Dancer Sean Lammer, Dancer Barry Gans, Dancer Dylan Cory, Dancer Julian Elia, Dancer Javon Jones, Dancer Nicolas Noguera, Dancer Canaries Natasha Warner, Writer, Director, and Choreographer Pablo O'Connell, Composer Esmé Boyce, Choreographer Jasminn Johnson, Actor Gwendolyn Ellis, Actor Victoria Pollack, Actor Jessica Savage, Actor Phoebe Dunn, Actor David Rosenberg, Actor Intermission (Program continues) Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

Royal Fireworks (1685-1759) Symphony No

MUSIC EMOJIS Feelings. Connections. Life. 2018 Sponsored by: S.E. Ainsworth and Family Teachers Guide 1 Music Emojis Feelings. Connections. Life La Rejouissance George Frideric Handel from Royal Fireworks (1685-1759) Symphony No. 1 (excerpt) Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) Music from Spiderman Danny Elfman (1953- ) Galop Dmitry Kabalevsky from The Comedians (1904-1987) Cello Concerto (3rd movement) Èdouard Lalo Ifetayo Ali-Landing, cello (1823-1892) Miller’s Dance Manuel de Falla from Three-Cornered Hat (1876-1946 ) Machine Jennifer Higdon (1962- ) Flying Theme John Williams from E.T. (1932- ) 2 With the increase of texting, email and other electronic communication in the last 20 years, face-to-face conversation or a phone call is often skirted by a quick text. It can be easier and less intrusive, but without any context of feeling behind them the words in these quick communications can be misunderstood. Emojis have the ability to express feelings wordlessly and can take the edge off of any text. They were invented by Shigetaka Kurita, who is a board member at a Tokyo technology company. He was a 25-year-old employee of a Japanese mobile carrier back in 1998 when he had the idea. His challenge was the 250 character limit and the need for some sort of shorthand. “Emoji” combines the Japanese for "picture," or "e'' (pronounced "eh"), and "letters," or "moji" (moh-jee). Apple and Google have made emojis a world sensation. What started as a few digital drawings has now become a gesture to communicate every conceivable emotion. They have been displayed in an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, earning a place in our culture and giving value to the design that has had the power to change lives. -

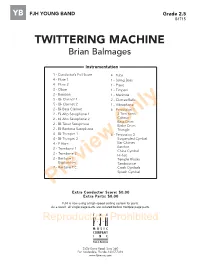

TWITTERING MACHINE Brian Balmages

YB FJH YOUNG BAND Grade 2.5 B1715 TWITTERING MACHINE Brian Balmages Instrumentation 1 - Conductor’s Full Score 4 - Tuba 4 - Flute 1 1 - String Bass 4 - Flute 2 1 - Piano 2 - Oboe 1 - Timpani 2 - Bassoon 1 - Marimba 5 - B≤ Clarinet 1 2 - Chimes/Bells 5 - B≤ Clarinet 2 1 - Vibraphone 2 - B≤ Bass Clarinet 4 - Percussion 1 2 - E≤ Alto Saxophone 1 2 Tom-toms Cabasa 2 - E≤ Alto Saxophone 2 Bass Drum 2 - B Tenor Saxophone ≤ Brake Drum 2 - E≤ Baritone Saxophone Triangle 4 - B≤ Trumpet 1 4 - Percussion 2 4 - B≤ Trumpet 2 Suspended Cymbal 4 - F Horn Bar Chimes 2 - Trombone 1 Ratchet China Cymbal 2 - Trombone 2 Hi-hat 2 - Baritone / Temple Blocks Euphonium Tambourine 2 - Baritone T.C. Crash Cymbals Preview SplashOnly Cymbal Extra Conductor Score: $0.00 Extra Parts: $0.00 FJH is now using a high-speed sorting system for parts. As a result, all single page parts are collated before multiple page parts. Reproduction Prohibited 2525 Davie Road, Suite 360 Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33317-7424 www.fjhmusic.com 2 The Composer Brian Balmages (b. 1975) is an award-winning composer, conductor, producer, and performer. The music he has written for winds, brass, and orchestra has been performed throughout the world with commissions ranging from elementary schools to professional orchestras. World premieres include prestigious venues such as Carnegie Hall, the Kennedy Center, and Meyerhoff Symphony Hall. His music was also performed as part of the 2013 Presidential Inaugural Prayer Service, which was attended by both President Obama and Vice President Biden. -

Burkholder/Grout/Palisca, Eighth Edition, Chapter 32 30 Chapter 32

30 11. SR: After WW I he founded/directed the __________. Between 19__ and 19__ the society gave approximately Chapter 32 ___ performances. He started the twelve-tone method in Modernism and the Classical Tradition 19__. His wife died and a year later he married ______. (He fathered __ children.) The Nazis came into power in 1. (810) What are the criteria established by the classics? 19__. Although Schoenberg had converted to _____, he converted back. From 19__, he taught at _____. He was forced to retire in 1944 because ________. He died on July __, 1951, a triskaidekaphobiac. 2. Modernists sought to challenge our ______ and _____. 12. SR: Make a list of his major works: 3. (811) Were they opposed to the classics? 4. What is the paradox of modern classical music? 5. All six composers in this chapter "began writing ____ music in the late _____ styles, but then found their own voice. 13. (813) SR: What's his position in the first paragraph? 6. What is the meaning of atonality? 14. SR: What's the essence of the second paragraph? 7. What is the twelve-tone method? 15. "The principle of _____ helps explain how Schoenberg's 8. Name the three works in the first paragraph of "Tonal music would evolve." Works" and name the influential composer. 16. (815) Explain "the emancipation of dissonance." 9. What compositional technique did he employ in his first 17. What were the three elements of Schoenberg's musical string quartet, Op. 7, D minor? What is the structure? organization? 10. -

World Premiere of Orpheus Alive with Company Premiere of Chaconne Opens November 15 Principal Casting Announced

World Premiere of Orpheus Alive with Company Premiere of Chaconne Opens November 15 Principal Casting Announced November 4, 2019 … Karen Kain, Artistic Director of The National Ballet of Canada, today announced the principal casting for the world premiere of Orpheus Alive by Choreographic Associate Robert Binet featuring a new commissioned score by acclaimed New York composer Missy Mazzoli. Orpheus Alive is paired with the company premiere of George Balanchine’s Chaconne November 15 – 21, 2019 at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts. #OrpheusAliveNBC #ChaconneNBC Artists have long been fascinated with the Greek myth of Orpheus, the gifted musician who rescues his lover Eurydice from death only to lose her again in a moment of doubt. At its core, theirs is a story about love, trust and the redemptive potential of art. With Orpheus Alive, Mr. Binet brings a fresh perspective to the myth, casting Orpheus as a woman, Eurydice as a man and the audience as gods of the underworld who decide their fate. The opening night cast on November 15 will feature First Soloist Jenna Savella and Second Soloist Spencer Hack as Orpheus and Eurydice along with Principal Dancer Sonia Rodriguez as Eurydice’s Mother. Subsequent performances will feature Principal Dancer Heather Ogden and First Soloist Hannah Fischer in the role of Orpheus, Principal Dancers Harrison James and Brendan Saye as Eurydice and First Soloist Tanya Howard as Eurydice’s Mother. In the music for Orpheus Alive, Ms. Mazzoli quotes Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice, setting the tone for George Balanchine’s Chaconne which features the same Gluck score. -

FMSO COMMISSION Or COMMISSION PARTICIPANT

FMSO COMMISSION or COMMISSION PARTICIPANT MAJOR COLLABORATION WITH OTHER ORGANIZATION/COMMUNITY OUTREACH PROJECT HYBRID PROGRAMMING – POPS/THEMATIC/TRADITIONAL AUDIO-VISUAL ENHANCEMENT LOCAL/YOUTH EMPHASIS MASTERWORKS SERIES PROGRAMMING – 2005 – Present 2018-2019 – EXPERIENCE THE SYMPHONY CHEE-YUN & SERGEY Dvorak – Slavonic Dances No. 2 & 7 Popper – Hungarian Rhapsody – with cellist SERGEY ANTONOV Liszt – Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Saint-Saëns – Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso – with violinist CHEE-YUN Brahms – Double Concert – with CHEE-YUN & SERGEY HIGDON HARP CONCERTO – regional premiere Mozart – Concerto for Flute & Harp, mvt. 2 – with harpist YOLANDA KONDONASSIS & Deb Harris Higdon – Harp Concerto – with harpist YOLANDA KONDONASSIS Nielsen – Symphony No. 4 “The Inextinguishable” MYTHICAL HEROES & WOMEN WARRIORS - with projected images Djawadi/Peterson – Music from “Game of Thrones” Smetana – “Sarka” from Ma Vlast (My Homeland) Shore – Music from “Lord of the Rings” Sibelius – Four Legends from the “Kalevala” (Lemminkainen Suite) THE VIRTUOSO NEXT DOOR – featuring FMSO musicians as soloists Shostakovich – Festive Overture (side by side with FMAYS Sr. High Orchestra) Poulenc – Double Piano Concerto – with pianists Jay Hershberger & Tyler Wottrich Tower – Fanfares for the Uncommon Woman – featuring FMSO brass & percussion Adams – Tromba Lontana – featuring FMSO trumpets Corigliano – Chaconne from “The Red Violin” CLAUSEN WORLD PREMIERE – FMSO COMMISSION Wagner/Clausen – “Elsa’s Procession to the Cathedral” from Lohengrin Copland – Appalachian Spring Clausen – TITLE TBA – FMSO Commission 2017-2018 – JUMP IN ALTERED STATES Hermann – Music from “Psycho” Corigliano – “Three Hallucinations” from Altered States Berlioz – Symphonie Fantastique THE ILLUMINATED SOUL – A COLLABORATION WITH THE ST. JOHN’S BIBLE PROJECT Bruch – Ave Maria (with cellist Inbal Segev) Bloch – Schelomo (with cellist Inbal Segev) Strauss – Death and Transfiguration Theofanidis – Rainbow Body (with projected images from The St. -

Performances from 1974 to 2020

Performances from 1974 to 2020 2019-20 December 1 & 2, 2018 Michael Slon, Conductor September 28 & 29, 2019 Family Holiday Concerts Benjamin Rous, Conductor MOZART Symphony No. 32 February 16 & 17, 2019 ROUSTOM Ramal Benjamin Rous, Conductor BRAHMS Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major RAVEL Pavane pour une infante défunte RAVEL Piano Concerto in G Major November 16 & 17, 2019 MOYA Siempre Lunes, Siempre Marzo Benjamin Rous & Michael Slon, Conductors KODALY Variations on a HunGarian FolksonG MONTGOMERY Caught by the Wind ‘The Peacock’ RICHARD STRAUSS Horn Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major March 23 & 24, 2019 MENDELSSOHN Psalm 42 Benjamin Rous, Conductor BRUCKNER Te Deum in C Major BARTOK Violin Concerto No. 2 MENDELSSOHN Symphony No. 4 in A Major December 6 & 7, 2019 Michael Slon, Conductor April 27 & 28, 2019 Family Holiday Concerts Benjamin Rous, Conductor WAGNER Prelude from Parsifal February 15 & 16, 2020 SCHUMANN Piano Concerto in A minor Benjamin Rous, Conductor SHATIN PipinG the Earth BUTTERWORTH A Shropshire Lad RESPIGHI Pines of Rome BRITTEN Nocturne GRACE WILLIAMS Elegy for String Orchestra June 1, 2019 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS On Wenlock Edge Benjamin Rous, Conductor ARNOLD Tam o’Shanter Overture Pops at the Paramount 2018-19 2017-18 September 29 & 30, 2018 September 23 & 24, 2017 Benjamin Rous, Conductor Benjamin Rous, Conductor BOWEN Concerto in C minor for Viola WALKER Lyric for StrinGs and Orchestra ADAMS Short Ride in a Fast Machine MUSGRAVE SonG of the Enchanter MOZART Clarinet Concerto in A Major SIBELIUS Symphony No. 2 in D Major BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7 in A Major November 17 & 18, 2018 October 6, 2017 Damon Gupton, Conductor Michael Slon, Conductor ROSSINI Overture to Semiramide UVA Bicentennial Celebration BARBER Violin Concerto WALKER Lyric for StrinGs TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No.