22 by Gretchen Horlacher a Fundamental Issue in the Analysis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky's Ballets. New Haven: Yale University

Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky’s Ballets. New Haven: Yale University Press. Reviewed by Maeve Sterbenz Charles M. Joseph’s recent monograph explores an important subset of Stravinsky’s complete oeuvre, namely his works for dance. One of the aims of the book is to stress the importance of dance for Stravinsky throughout his career as a source of inspiration that at times significantly shaped his develop- ment as a composer. Joseph offers richly contextualized and detailed pictures of Stravinsky’s ballets, ones that will be extremely useful for both dance and music scholars. While he isolates each work, several themes run through Joseph’s text. Among the most important are Stravinsky’s self–positioning as simultaneously Russian and cosmopolitan; and Stravinsky’s successes in collaboration, through which he was able to create fully integrated ballets that elevated music’s traditionally subservient role in relation to choreography. To begin, Joseph introduces his motivation for the project, arguing for the necessity of an in–depth study of Stravinsky’s works for dance in light of the fact that they comprise a significant fraction of the composer’s output (more so than any other Western classical composer) and that these works, most notably The Rite of Spring, occupy such a prominent place in the Western canon. According to Joseph, owing to Stravinsky’s sensitivity to the “complexly subtle counterpoint between ballet’s interlocking elements” (xv), the ballets stand out in the genre for their highly interdisciplinary nature. In the chapters that follow, Joseph examines each of the ballets, focusing alternately on details of the works, histories of their production and reception, and their biographical contexts. -

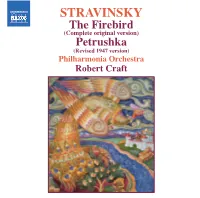

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise. -

The University of Chicago an Experience-Oriented

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO AN EXPERIENCE-ORIENTED APPROACH TO ANALYZING STRAVINSKY’S NEOCLASSICISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY SARAH MARIE IKER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 CONTENTS List of Figures ...................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ..................................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................... ix Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. x Introduction: Analysis, Experience, and Experience-Oriented Analysis ..................................... 1 1 Neoclassicism, Analysis, and Experience ................................................................................ 10 1.1 Neoclassicism After the Great War ................................................................................. 10 1.2 Analyzing Neoclassicism: Problems and Solutions ....................................................... 18 1.3 Whence Listener Experience? ........................................................................................... 37 1.4 The Problem of Historicism ............................................................................................ -

The Firebird

EDUCATION Education RESOURCE THE WITH PAQUITA SUPPORTED BY NATIONAL TOURING SUPPORTING EDUCATION CHOREOGRAPHER VAL CANIPAROLI PARTNER rnzb.org.nz facebook.com/nzballet CONTENTS Curriculum links 3 The Firebird 4 The characters 4 The story 5 The creatives 7 Q&A with Loughlan Prior 12 The history of The Firebird 14 Dance activities 16 Crafts and puzzles 18 What to do at a ballet 22 Ballet timeline 23 THE FIREBIRD 29 JULY – 2 SEPTEMBER 2021 2 CURRICULUM LINKS In this unit you and your students will: WORKSHOP LEARNING • Learn about the elements that come OBJECTIVES FOR together to create a theatrical ballet LEVELS 3 & 4 experience. Level 3 students will learn how to: • Identify the processes involved in Develop practical knowledge making a theatre production. • Use the dance elements to develop and share their personal movement vocabulary. CURRICULUM LINKS IN Develop ideas THIS UNIT • Select and combine dance elements in response to a variety of stimuli. Values Communicate and interpret Students will be encouraged to value: • Prepare and share dance movement • Innovation, inquiry and curiosity, individually and in pairs or groups. by thinking critically, creatively and • Use the elements of dance to describe dance reflectively. movements and respond to dances from a • Diversity, as found in our different cultures variety of cultures. and heritages. • Community and participation for the Level 4 students will learn how to: common good. Develop practical knowledge • Apply the dance elements to extend personal KEY COMPETENCIES movement skills and vocabularies and to explore the vocabularies of others. • Using language, symbols and text – Develop ideas Students will recognise how choices of • Combine and contrast the dance elements to language and symbols in live theatre affect express images, ideas, and feelings in dance, people’s understanding and the ways in using a variety of choreographic processes. -

Mengjiao Yan Phd Thesis.Pdf

The University of Sheffield Stravinsky’s piano works from three distinct periods: aspects of performance and latitude of interpretation Mengjiao Yan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music The University of Sheffield Jessop Building, Sheffield, S3 7RD, UK September 2019 1 Abstract This research project focuses on the piano works of Igor Stravinsky. This performance- orientated approach and analysis aims to offer useful insights into how to interpret and make informed decisions regarding his piano music. The focus is on three piano works: Piano Sonata in F-Sharp Minor (1904), Serenade in A (1925), Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1958–59). It identifies the key factors which influenced his works and his compositional process. The aims are to provide an informed approach to his piano works, which are generally considered difficult and challenging pieces to perform convincingly. In this way, it is possible to offer insights which could help performers fully understand his works and apply this knowledge to performance. The study also explores aspects of latitude in interpreting his works and how to approach the notated scores. The methods used in the study include document analysis, analysis of music score, recording and interview data. The interview participants were carefully selected professional pianists who are considered experts in their field and, therefore, authorities on Stravinsky's piano works. The findings of the results reveal the complex and multi-faceted nature of Stravinsky’s piano music. The research highlights both the intrinsic differences in the stylistic features of the three pieces, as well as similarities and differences regarding Stravinsky’s compositional approach. -

The Late Choral Works of Igor Stravinsky

THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY _________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ by RUSTY DALE ELDER Dr. Michael Budds, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, as appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY presented by Rusty Dale Elder, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________________ Professor Michael Budds ________________________________________ Professor Judith Mabary _______________________________________ Professor Timothy Langen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to each member of the faculty who participated in the creation of this thesis. First and foremost, I wish to recognize the ex- traordinary contribution of Dr. Michael Budds: without his expertise, patience, and en- couragement this study would not have been possible. Also critical to this thesis was Dr. Judith Mabary, whose insightful questions and keen editorial skills greatly improved my text. I also wish to thank Professor Timothy Langen for his thoughtful observations and support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………...ii ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: THE PROBLEM OF STRAVINSKY’S LATE WORKS…....1 Methodology The Nature of Relevant Literature 2. “A BAD BOY ALL THE WAY”: STRAVINSKY’S SECOND COMPOSITIONAL CRISIS……………………………………………………....31 3. AFTER THE BOMB: IN MEMORIAM DYLAN THOMAS………………………45 4. “MURDER IN THE CATHEDRAL”: CANTICUM SACRUM AD HONOREM SANCTI MARCI NOMINIS………………………………………………………...60 5. -

Mitsuko Uchida Conductor and Piano Stravinsky Concerto in D Major for String Orchestra Mozart Piano Concerto No. 18 in B-Flat Ma

Program ONE huNDRED TwENTy-FiRST SEASON Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music Director Pierre Boulez helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, March 29, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, March 30, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, March 31, 2012, at 8:00 Sunday, April 1, 2012, at 3:00 mitsuko Uchida Conductor and Piano Stravinsky Concerto in D Major for String Orchestra Vivace— Arioso: Andantino— Rondo: Allegro mozart Piano Concerto No. 18 in B-flat Major, K. 456 Allegro vivace Andante un poco sostenuto Allegro vivace MiTSuKO uChiDA IntermISSIon mozart Adagio and Fugue in C Minor, K. 546 mozart Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-flat Major, K. 271 (Jeunehomme) Allegro Andantino Rondo: Presto MiTSuKO uChiDA Saturday’s concert is sponsored by Walgreens. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommentS By PhilliP huSChER Igor Stravinsky Born June 18, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia. Died April 6, 1971, New York City. Concerto in D major for String orchestra hortly after Stravinsky con- (and her husband, Franz Werfel), Sducted the world premiere of Rubinstein, and Aldous Huxley, his Symphony in C in Chicago who hooked him up with W. H. in November 1940, he and his Auden to work on The Rake’s new wife Vera bought a house at Progress. Mann later said that 1260 North Wetherly in West “Hollywood during the war was Hollywood. In the spring of 1941, a more intellectually stimulat- they moved in. -

An Explanation of Anomalous Hexachords in Four Serial Works by Igor Stravinsky

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2011 An Explanation of Anomalous Hexachords in Four Serial Works by Igor Stravinsky Robert Sivy [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert, "An Explanation of Anomalous Hexachords in Four Serial Works by Igor Stravinsky. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2011. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1025 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Robert Sivy entitled "An Explanation of Anomalous Hexachords in Four Serial Works by Igor Stravinsky." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Brendan P. McConville, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Barbara Murphy, Donald Pederson Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) An Explanation of Anomalous Hexachords in Four Serial Works by Igor Stravinsky A Thesis Presented for the Master of Music Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Robert Jacob Sivy August 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Robert Jacob Sivy All rights reserved. -

For Immediate Release NEW WORLD SYMPHONY and MIAMI CITY

For Immediate Release NEW WORLD SYMPHONY AND MIAMI CITY BALLET TO CELEBRATE LEGACY OF IGOR STRAVINSKY AND GEORGE BALANCHINE WITH LIVE-STREAMED WALLCAST® EVENT AT NEW WORLD CENTER, SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 1 AT 7:30 P.M. ET Collaboration inspired by NWS Artistic Director Michael Tilson Thomas’s and MCB Artistic Director Lourdes Lopez’s personal connections to Stravinsky and Balanchine WALLCAST® event to be projected live for audience attending free of charge at SoundScape Park; free webcast to be available on Medici.tv Left: New World Symphony, conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas. Right: Miami City Ballet performance. MIAMI BEACH, FLORIDA (November 25, 2019) — On Saturday, February 1, at 7:30 p.m. ET, the New World Symphony, America’s Orchestral Academy (NWS), and Miami City Ballet (MCB) come together for a special live-streamed WALLCAST® event celebrating Igor Stravinsky and George Balanchine, two icons of the 20th century whose decades-long friendship proved to be one of the most prolific artistic pairings of their time. Led by NWS Co-Founder and Artistic Director Michael Tilson Thomas (MTT), this performance at the New World Center is projected live on the 7,000-sq.-ft. eastern façade of the building and may be experienced for free in adjacent SoundScape Park. Additionally, a free live- stream is available to viewers around the world via Medici.tv. Curated by MTT and MCB Artistic Director Lourdes Lopez, who as young artists worked with Stravinsky and Balanchine respectively, the program on both evenings comprises Stravinsky- Balanchine’s Apollon musagète; Balanchine’s Stravinsky Violin Concerto, featuring violinist James Ehnes; and Stravinsky’s Circus Polka: For a Young Elephant, originally choreographed for circus elephants and ballerinas by Balanchine on commission from Ringling Bros. -

—John Lahr Cussion

1 figure, or what Duchamp termed “retinal art”? The answer is all of the above. This beautifully installed, CRITIC’S NOTEBOOK whip-smart exhibition features works such as a cracked and cloudy crystal ball that was rolled from AW NE DAWN its place of purchase to the gallery, a collaboration between Nina Beier and Marie Lund; a series of paintings by Pavel Büchler, composed of fragments When it was first produced, from found flea-market canvases; Nina Canell’s al- in 1946, Garson Kanin’s chemical assemblage, in which a bowl of water dis- solving into mist hardens a nearby bag of cement; “Born Yesterday” made a and Monica Bonvicini’s fractured safety-glass cube, star of Judy Holliday, who which gives the finger to minimalism. Destroy away: art rises, ever phoenixlike, from the ashes. Through played Billie Dawn, the May 8. (Swiss Institute, 495 Broadway, at Broome bimbo turned bookworm. 1St. 212-925-2035.) The splendid new revival, directed by Doug Hughes DANCE at the Cort, makes a star NEW YORK CITY BALLET The company goes back to basics, with seven days of Balanchine’s “black-and-white” dances, modern- ist masterpieces that have come to define the style and look of twentieth-century American ballet. In “Apollo” (1928)—set, like many of these works, to music by Igor Stravinsky—a “wild, untamed youth,” the dancer Jacques d’Amboise says, “learns nobility through art.” “Episodes,” from 1959, began as a double bill shared by Martha Graham and George Balanchine, and hasn’t been performed here in four years. And “Concerto Barocco” (1941), for two violins and two ballerinas, comes as close to revealing the essence of Bach as any dance ever will. -

Kirstein and Balanchine's New York City Ballet Four Modern Works

23 Kirstein and Balanchine’s New York City Ballet Four Modern Works 1 Mar 16–18, 2019, Presented in conjunction with the exhibition Lincoln The Four Music by Paul Hindemith 12:00 and 3:00 p.m., Kirstein’s Modern (March 17–June 15, 2019), this three- Temperaments (1946) Choreography by George Balanchine* The Donald B. and day event features eighteen dancers from New York [excerpts] Catherine C. Marron City Ballet performing excerpts from four landmark Original costume and scenic designs by Kurt Seligmann Atrium works created by George Balanchine, the legendary (performed in practice clothes and without scenery from choreographer who cofounded the company with 1951) Lincoln Kirstein in 1948. The program, organized by NYCB Artistic Director Jonathan Stafford, will be “First Theme” performed by Meaghan Dutton-O’Hara moderated by NYCB corps de ballet member Silas Farley and Andrew Scordato and accompanied by NYCB solo pianist Elaine Chelton. “Second Theme” performed by Sara Adams and Devin Alberda In 1933, Kirstein—a writer, curator, editor, impresario, “Third Theme” performed by Miriam Miller and Peter tastemaker, and patron—invited the Russian-born Walker Balanchine to New York from Paris, in the hopes of creating a uniquely American ballet. They established First Variation: Melancholic the School of American Ballet (1934), and in the ensuing Performed by Anthony Huxley with Laine Habony and years, founded—together or separately—the precursor Olivia MacKinnon, and Eliza Blutt, Meaghan Dutton- companies American Ballet (1935), Ballet Caravan O’Hara, Mary Thomas MacKinnon, and Miriam Miller (1936), American Ballet Caravan (1941), and Ballet Society (1946). The score for The Four Temperaments is based on the Kirstein, who also played a key role in MoMA’s early ancient medical notion that human personalities are history, believed in the central place of dance in the determined by four humors—Melancholic, Sanguine, museum. -

Igor Stravinsky, One of the Greatest Masters of Modern Music, Was Born in Oranienbaum, Near St

FROM: AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE 890 Broadway New York, New York 10003 (212) 477-3030 Kelly Ryan IGOR (FEDOROVITCH) STRAVINSKY Igor Stravinsky, one of the greatest masters of modern music, was born in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, on June 17, 1882. The son of a famous bass singer at the Imperial Opera, Feodor Stravinsky, he was raised in an artistic atmosphere. He studied law until age nineteen, when Rimsky- Korsakov in Heidelberg encouraged him to study composition seriously and he studied theory with Kalafati. In 1907, Stravinsky studied with Rimsky-Korsakov in St. Petersburg and on January 22, 1908, his first symphony, which showed a mastery of technique, was performed in St. Petersburg. This was followed on February 29, by his critically successful set of songs for mezzo-soprano and orchestra, Le Faune et la Bergere. In celebration of Maxmillian Steinberg's marriage to Rimsky-Korsakov's daughter (June 17, 1908), Stravinsky wrote an orchestral fantasy, Feu d'artifice, and when Rimsky-Korsakov died a few days later, he wrote a threnody as a tribute. Stravinsky's next orchestral work, Scherzo fantastique, was performed in St. Petersburg (February 6, 1909) and the famous impresario, Diaghilev, heard it and commissioned Stravinsky to write a work on a Russian subject. The result was the production of the first of Stravinsky's ballet masterpieces, L'Oiseau de feu (Paris, June 15, 1910) and the beginning of the successful collaboration between the composer and producer. Stravinsky’s association with Diaghilev concentrated his activities in Paris and he moved there in 1911. His second ballet for the impresario, Petrouchka, (Paris, June 13, 1911), was a great success and was so new and original that it marked a turning point in 20th century modernism.