Theory of Music-Stravinsky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

All Strings Considered a Subjective List of Classical Works

All Strings Considered A Subjective List of Classical Works & Recordings All Recordings are available from the Lake Oswego Public Library These are my faves, your mileage may vary. Bill Baars, Director Composer / Title Performer(s) Comments Middle Ages and Renaissance Sequentia We carry a lot of plainsong and chant; HILDEGARD OF BINGEN recordings by the Anonymous 4 are also Antiphons highly recommended. Various, Renaissance vocal and King’s Consort, Folger Consort instrumental collections. or Baltimore Consort Baroque Era Biondi/Europa Galante or Vivaldi wrote several hundred concerti; try VIVALDI Loveday/Marriner. the concerti for multiple instruments, and The Four Seasons the Mandolin concerti. Also, Corelli's op. 6 and Tartini (my fave is his op.96). HANDEL Asch/Scholars Baroque For more Baroque vocal, Bach’s cantatas - Messiah Ensemble, Shaw/Atlanta start with 80 & 140, and his Bach B Minor Symphony Orch. or Mass with John Gardiner conducting. And for Jacobs/Freiberg Baroque fun, Bach's “Coffee” cantata. orch. HANDEL Lamon/Tafelmusik For an encore, Handel's “Music for the Royal Water Music Suites Fireworks.” J.S. BACH Akademie für Alte Musik Also, the Suites for Orchestra; the Violin and Brandenburg Concertos Berlin or Koopman, Pinnock, Harpsicord Concerti are delightful, too. or Tafelmusik J.S. BACH Walter Gerwig More lute - anything by Paul O'Dette, Ronn Works for Lute McFarlane & Jakob Lindberg. Also interesting, the Lute-Harpsichord. J.S. BACH Bylsma on period cellos, Cello Suites Fournier on a modern instrument; Casals' recording was the standard Classical Era DuPre/Barenboim/ECO & HAYDN Barbirolli/LSO Cello Concerti HAYDN Fischer, Davis or Kuijiken "London" Symphonies (93-101) HAYDN Mosaiques or Kodaly quartets Or start with opus 9, and take it from there. -

Children's Concert Series an INTERACTIVE CONCERT WITH

Children’s Concert Series 2020–2021 AN INTERACTIVE CONCERT WITH MUSIC, DANCE, AND NARRATION Saturday, March 13, 2021 | 6:00 pm Virtual Family Concert 1 ver fifty years ago, a brave American man stepped out of a landing craft onto the surface Gerard Schwarz of the moon and made history. With the help of Conductor O the Demetrius Klein Dance Company and four exciting pieces of all-American music, Palm Beach Symphony Brenda Alford brings that indelible moment of Milky Way magic to the Narrator stage through an interactive concert in which students will literally take part in exploring such scientific concepts as Demetrius Klein Dance Company (DKDC) the Earth’s rotation, gravity and telescope viewing. All this choreography and dance while thrilling to a powerful Copland fanfare, the soaring themes of Star Wars and sharing the adventures of a very special resident of Earth’s satellite, Rocky de Luna, an Saturday, March 13, 2021 | 6:00 pm inquisitive moon rock. Virtual Family Concert With a special narrative accompanied by the music of Copland’s Lincoln Portrait, students will meet Rocky as she hitches a ride with two friendly NASA astronauts on the Program Apollo 11 lunar module en route back to Aaron Copland – Fanfare for the Common Man planet Earth. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin show Rocky some out-of-this-world John Williams – Princess Leia’s Theme from Star Wars views of the moon, help define the moon’s John Williams – The Imperial March (Darth Vader’s Theme) from Star Wars place in the solar system, describe how the moon Aaron Copland – Selections from Lincoln Portrait affects all life on Earth .. -

Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: the Success of Arthur Honeggerâ•Žs Antigone in Vichy France

Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 7 2021 Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: The Success of Arthur Honegger’s Antigone in Vichy France Emma K. Schubart University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur Recommended Citation Schubart, Emma K. (2021) "Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: The Success of Arthur Honegger’s Antigone in Vichy France," Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 7 , Article 4. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur/vol7/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH, VOLUME 7 MUSICAL HYBRIDIZATION AND POLITICAL CONTRADICTION: THE SUCCESS OF ARTHUR HONEGGER’S ANTIGONE IN VICHY FRANCE EMMA K. SCHUBART, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL MENTOR: SHARON JAMES Abstract Arthur Honegger’s modernist opera Antigone appeared at the Paris Opéra in 1943, sixteen years after its unremarkable premiere in Brussels. The sudden Parisian success of the opera was extraordinary: the work was enthusiastically received by the French public, the Vichy collaborationist authorities, and the occupying Nazi officials. The improbable wartime triumph of Antigone can be explained by a unique confluence of compositional, political, and cultural realities. Honegger’s compositional hybridization of French and German musical traditions, as well as his opportunistic commercial motivations as a Swiss composer working in German-occupied France, certainly aided the success of the opera. -

Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky's Ballets. New Haven: Yale University

Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky’s Ballets. New Haven: Yale University Press. Reviewed by Maeve Sterbenz Charles M. Joseph’s recent monograph explores an important subset of Stravinsky’s complete oeuvre, namely his works for dance. One of the aims of the book is to stress the importance of dance for Stravinsky throughout his career as a source of inspiration that at times significantly shaped his develop- ment as a composer. Joseph offers richly contextualized and detailed pictures of Stravinsky’s ballets, ones that will be extremely useful for both dance and music scholars. While he isolates each work, several themes run through Joseph’s text. Among the most important are Stravinsky’s self–positioning as simultaneously Russian and cosmopolitan; and Stravinsky’s successes in collaboration, through which he was able to create fully integrated ballets that elevated music’s traditionally subservient role in relation to choreography. To begin, Joseph introduces his motivation for the project, arguing for the necessity of an in–depth study of Stravinsky’s works for dance in light of the fact that they comprise a significant fraction of the composer’s output (more so than any other Western classical composer) and that these works, most notably The Rite of Spring, occupy such a prominent place in the Western canon. According to Joseph, owing to Stravinsky’s sensitivity to the “complexly subtle counterpoint between ballet’s interlocking elements” (xv), the ballets stand out in the genre for their highly interdisciplinary nature. In the chapters that follow, Joseph examines each of the ballets, focusing alternately on details of the works, histories of their production and reception, and their biographical contexts. -

A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music

1 Kristen Masada and Razvan Bunescu: A Segmental CRF Model for Chord Recognition in Symbolic Music A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music minished triads most frequently contain a diminished A chord is a group of notes that form a cohesive har- seventh interval (9 half steps), producing a fully di- monic unit to the listener when sounding simulta- minished seventh chord, or a minor seventh interval, neously (Aldwell et al., 2011). We design our sys- creating a half-diminished seventh chord. tem to handle the following types of chords: triads, augmented 6th chords, suspended chords, and power A.2 Augmented 6th Chords chords. An augmented 6th chord is a type of chromatic chord defined by an augmented sixth interval between the A.1 Triads lowest and highest notes of the chord (Aldwell et al., A triad is the prototypical instance of a chord. It is 2011). The three most common types of augmented based on a root note, which forms the lowest note of a 6th chords are Italian, German, and French sixth chord in standard position. A third and a fifth are then chords, as shown in Figure 8 in the key of A minor. built on top of this root to create a three-note chord. In- In a minor scale, Italian sixth chords can be seen as verted triads also exist, where the third or fifth instead iv chords with a sharpened root, in the first inversion. appears as the lowest note. The chord labels used in Thus, they can be created by stacking the sixth, first, our system do not distinguish among inversions of the and sharpened fourth scale degrees. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

22 by Gretchen Horlacher a Fundamental Issue in the Analysis Of

Sketches and Superimposition in Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms by Gretchen Horlacher A fundamental issue in the analysis of Stravinsky’s music is to describe how the composer juxtaposes and superimposes repeating motivic fragments. Do layered ostinati spin out in opposition to one another or do they interact? Does the progress of one affect the progress of another? Do they create for- mal relationships beyond their own repetitions? Evidence in sketches for works spanning the Russian period through the early serial work Agon (1953–57) suggests that this issue was a primary concern for the composer: many sketches and drafts are dedicated to working out the relationships be- tween and among simultaneously sounding strata so that they jointly shape passages of music. These documents share a common working method. Early in the composi- tional process, Stravinsky seems often to have drafted short “phrases” where the constituent motivic fragments are placed in relationship but repeated only briefly or not at all; subsequent drafts expand the lengths of phrases by in- serting repetitions of existing material into the original phrases.1 Such a pro- cedure allows us to compare the longer (and most often retained) versions with their shorter predecessors, giving us insight both into how Stravinsky develops his material and what might constitute a complete formal unit. In other words, we can trace the expansions of phrases through interpolation in order to identify how later versions have a more continuous formal shape and fit more easily into larger formal units. Consider as an example two sketches for a passage from the third move- ment of the Symphony of Psalms (1929–30); the two sketches are reproduced as Examples 1a and 1b and the final score is reproduced as Example 2.2 A pre- liminary description of the passage might go as follows. -

ESO Highnotes November 2020

HighNotes is brought to you by the Evanston Symphony Orchestra for the senior members of our community who must of necessity isolate more because of COVID-!9. The current pandemic has also affected all of us here at the ESO, and we understand full well the frustration of not being able to visit with family and friends or sing in soul-renewing choirs or do simple, familiar things like choosing this apple instead of that one at the grocery store. We of course miss making music together, which is especially difficult because Musical Notes and Activities for Seniors this fall marks the ESO’s 75th anniversary – our Diamond Jubilee. While we had a fabulous season of programs planned, we haven’t from the Evanston Symphony Orchestra been able to perform in a live concert since February so have had to push the hold button on all live performances for the time being. th However, we’re making plans to celebrate our long, lively, award- Happy 75 Anniversary, ESO! 2 winning history in the spring. Until then, we’ll continue to bring you music and musical activities in these issues of HighNotes – or for Aaron Copland An American Voice 4 as long as the City of Evanston asks us to do so! O’Connor Appalachian Waltz 6 HighNotes always has articles on a specific musical theme plus a variety of puzzles and some really bad jokes and puns. For this issue we’re focusing on “Americana,” which seems appropriate for Gershwin Porgy and Bess 7 November, when we come together as a country to exercise our constitutional right and duty to vote for candidates of our choice Bernstein West Side Story 8 and then to gather with our family and friends for Thanksgiving and completely spoil a magnificent meal by arguing about politics… ☺ Tate Music of Native Americans 9 But no politics here, thank you! “Bygones” features things that were big in our childhoods, but have now all but disappeared. -

Year 11 Music Revision Guide

Year 11 Music Revision Guidance Name the musical instrument In the exam you will be asked to name different instruments that you can hear playing. If you do not play one of these instruments it can sometimes be quite difficult to pick out what each one sounds like. You will need to know what the different instruments of the orchestra sound like, what popular musical instruments sound like and what some world instruments sound like (sitar). It is worth you visiting www.dsokids.com or www.compositionlab.co.uk where you will be able to hear these instruments individually. Describing musical sounds For some questions in the exam you will need to describe what is happening in the music, in detail! If you are asked to comment on what is happening in the music you may need to describe what a particular instrument is doing, for example: ‘The left hand of the piano is playing ascending arpeggios’. The more detail you can provide, the better! Melodic movement You may be asked to describe what is happening in the melody of a song. Remember, this means the main tune. In popular music this is often the vocal line or in instrumental music it can be described as the instrument that has the main tune (the bit that you could whistle). It could move by STEP; this means it moves to the note next to it. It could move by LEAP; this means that the melody jumps from one note to another but misses some notes out in between. This could be a low note jumping to a high note or vice versa. -

A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form

MODERN FORMS OF AN ANCIENT ART: A SELECTION OF CONTEMPORARY FANFARES FOR MULTIPLE TRUMPETS DEMONSTRATING EVOLUTIONARY PROCESSES IN THE FANFARE FORM Paul J. Florek, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2015 APPROVED: Keith Johnson, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Florek, Paul J. Modern Forms of an Ancient Art: A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2015, 73 pp., 1 table, 26 figures, references, 96 titles. The pieces discussed throughout this dissertation provide evidence of the evolution of the fanfare and the ability of the fanfare, as a form, to accept modern compositional techniques. While Britten’s Fanfare for St. Edmundsbury maintains the harmonic series, it does so by choice rather than by the necessity in earlier music played by the baroque trumpet. Stravinsky’s Fanfare from Agon applies set theory, modal harmonies, and open chords to blend modern techniques with medieval sounds. Satie’s Sonnerie makes use of counterpoint and a rather unusual, new characteristic for fanfares, soft dynamics. Ginastera’s Fanfare for Four Trumpets in C utilizes atonality and jazz harmonies while Stravinsky’s Fanfare for a New Theatre strictly coheres to twelve-tone serialism. McTee’s Fanfare for Trumpets applies half-step dissonance and ostinato patterns while Tower’s Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman demonstrates a multi-section work with chromaticism and tritones. -

Academiccatalog 2017.Pdf

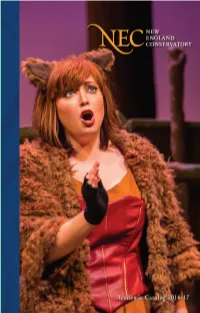

New England Conservatory Founded 1867 290 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 necmusic.edu (617) 585-1100 Office of Admissions (617) 585-1101 Office of the President (617) 585-1200 Office of the Provost (617) 585-1305 Office of Student Services (617) 585-1310 Office of Financial Aid (617) 585-1110 Business Office (617) 585-1220 Fax (617) 262-0500 New England Conservatory is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. New England Conservatory does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, age, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, physical or mental disability, genetic make-up, or veteran status in the administration of its educational policies, admission policies, employment policies, scholarship and loan programs or other Conservatory-sponsored activities. For more information, see the Policy Sections found in the NEC Student Handbook and Employee Handbook. Edited by Suzanne Hegland, June 2016. #e information herein is subject to change and amendment without notice. Table of Contents 2-3 College Administrative Personnel 4-9 College Faculty 10-11 Academic Calendar 13-57 Academic Regulations and Information 59-61 Health Services and Residence Hall Information 63-69 Financial Information 71-85 Undergraduate Programs of Study Bachelor of Music Undergraduate Diploma Undergraduate Minors (Bachelor of Music) 87 Music-in-Education Concentration 89-105 Graduate Programs of Study Master of Music Vocal Pedagogy Concentration Graduate Diploma Professional String Quartet Training Program Professional