Arxiv:2004.13945V2 [Cs.CL] 17 Aug 2021 Institute of Technology (BHU), India, Varanasi, U.P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Hindi, an Indo-European language, is the official language of India, spoken by about 40% of the more than one billion citizens of India. It is also the official language in certain of the territories where a sizeable diaspora settled such as the Republic of Mauritius1. But the label ‘Hindi’ covers considerably distinct speeches, as evidenced by the number of regional varieties covered by the category Hindi in the various Censuses of India: 91 mother tongues in the 1961 Census, up to 331 languages or speeches according to Srivastava 1994, totalizing to six hundred millions speakers (Bhatia 1987: 9). On the other end, the notion that Standard Hindi, more or less corresponding to the variety used in written literature and media, does not exist as a mother tongue, has gained currency during the seventies and eighties: according to Gumperz & Naim (1960), modern standard Hindi is a second or third speech for most of its speakers, being a native language for a small section of the urban population, which until recently was itself a small minority of the global Indian population. However, due to the rapid increase in this urban population, Hindi native speakers can no longer be considered as a non-significant minority, as noticed by Ohala (1983) and Singh & Agnihotri (1997). Many scholars still consider that the modern colloquial language, used for instance in popular movies, does not differ from modern colloquial Urdu. Similarly, many consider that the higher registers of both languages are still only two styles of one and the same language. According to Abdul Haq (1961), “the language we speak and write and call by the name Urdu today is derived from Hindi and constituted of Hindi”. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Linguistic Survey of India Bihar

LINGUISTIC SURVEY OF INDIA BIHAR 2020 LANGUAGE DIVISION OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA i CONTENTS Pages Foreword iii-iv Preface v-vii Acknowledgements viii List of Abbreviations ix-xi List of Phonetic Symbols xii-xiii List of Maps xiv Introduction R. Nakkeerar 1-61 Languages Hindi S.P. Ahirwal 62-143 Maithili S. Boopathy & 144-222 Sibasis Mukherjee Urdu S.S. Bhattacharya 223-292 Mother Tongues Bhojpuri J. Rajathi & 293-407 P. Perumalsamy Kurmali Thar Tapati Ghosh 408-476 Magadhi/ Magahi Balaram Prasad & 477-575 Sibasis Mukherjee Surjapuri S.P. Srivastava & 576-649 P. Perumalsamy Comparative Lexicon of 3 Languages & 650-674 4 Mother Tongues ii FOREWORD Since Linguistic Survey of India was published in 1930, a lot of changes have taken place with respect to the language situation in India. Though individual language wise surveys have been done in large number, however state wise survey of languages of India has not taken place. The main reason is that such a survey project requires large manpower and financial support. Linguistic Survey of India opens up new avenues for language studies and adds successfully to the linguistic profile of the state. In view of its relevance in academic life, the Office of the Registrar General, India, Language Division, has taken up the Linguistic Survey of India as an ongoing project of Government of India. It gives me immense pleasure in presenting LSI- Bihar volume. The present volume devoted to the state of Bihar has the description of three languages namely Hindi, Maithili, Urdu along with four Mother Tongues namely Bhojpuri, Kurmali Thar, Magadhi/ Magahi, Surjapuri. -

Honorificity, Indexicality and Their Interaction in Magahi

SPEAKER AND ADDRESSEE IN NATURAL LANGUAGE: HONORIFICITY, INDEXICALITY AND THEIR INTERACTION IN MAGAHI BY DEEPAK ALOK A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Linguistics Written under the direction of Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Speaker and Addressee in Natural Language: Honorificity, Indexicality and their Interaction in Magahi By Deepak Alok Dissertation Director: Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal Natural language uses first and second person pronouns to refer to the speaker and addressee. This dissertation takes as its starting point the view that speaker and addressee are also implicated in sentences that do not have such pronouns (Speas and Tenny 2003). It investigates two linguistic phenomena: honorification and indexical shift, and the interactions between them, andshow that these discourse participants have an important role to play. The investigation is based on Magahi, an Eastern Indo-Aryan language spoken mainly in the state of Bihar (India), where these phenomena manifest themselves in ways not previously attested in the literature. The phenomena are analyzed based on the native speaker judgements of the author along with judgements of one more native speaker, and sometimes with others as the occasion has presented itself. Magahi shows a rich honorification system (the encoding of “social status” in grammar) along several interrelated dimensions. Not only 2nd person pronouns but 3rd person pronouns also morphologically mark the honorificity of the referent with respect to the speaker. -

A Language Without a State: Early Histories of Maithili Literature

A LANGUAGE WITHOUT A STATE: EARLY HISTORIES OF MAITHILI LITERATURE Lalit Kumar When we consider the more familiar case of India’s new national language, Hindi, in relation to its so-called dialects such as Awadhi, Brajbhasha, and Maithili, we are confronted with the curious image of a thirty-year-old mother combing the hair of her sixty-year-old daughters. —Sitanshu Yashaschandra The first comprehensive history of Maithili literature was written by Jayakanta Mishra (1922-2009), a professor of English at Allahabad University, in two volumes in 1949 and 1950, respectively. Much before the publication of this history, George Abraham Grierson (1851- 1941), an ICS officer posted in Bihar, had first attempted to compile all the available specimens of Maithili literature in a book titled Maithili Chrestomathy (1882).1 This essay analyses Jayakanta Mishra’s History in dialogue with Grierson’s Chrestomathy, as I argue that the first history of Maithili literature was the culmination of the process of exploration of literary specimens initiated by Grierson, with the stated objective of establishing the identity of Maithili as an independent modern Indian language.This journey from Chrestomathy to History, or from Grierson to Mishra,helps us understand not only the changes Maithili underwent in more than sixty years but also comprehend the centrality of the language-dialect debate in the history of Maithili literature. A rich literary corpus of Maithili created a strong ground for its partial success, not in the form of Mithila getting the status of a separate state, but in the official recognition by the Sahitya Akademi in 1965 and by the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution in 2003. -

Multilingual Education and Nepal Appendix 3

19. Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove and Mohanty, Ajit. Policy and Strategy for MLE in Nepal Report by Tove Skutnabb-Kangas and Ajit Mohanty Consultancy visit 4-14 March 2009i Sanothimi, Bhaktapur: Multilingual Education Program for All Non-Nepali Speaking Students of Primary Schools of Nepal. Ministry of Education, Department of Education, Inclusive Section. See also In Press, for an updated version. List of Contents List of Contents List of Appendices List of Tables List of Figures List of Abbreviations 1. Introduction: placing language in education issues in Nepal in a broader societal, economic and political framework 2. Broader Language Policy and Planning Perspectives and Issues 2.1. STEP 1 in Language Policy and Language Planning: Broad-based political debates about the goals of language 2.2. STEP 2 in Educational Language Policy and Language Planning: Realistic language proficiency goal/aim in relation to the baseline 2.3. STEP 3 in Educational Language Planning: ideal goals and prerequisites compared with characteristics of present schools 2.4. STEP 4 in Educational Language Planning: what has characterized programmes with high versus low success? 2.5. STEP 5 in Educational Language Planning: does it pay off to maintain ITM languages? 3. Scenarios 3.1. Introduction 3.2. Models with often harmful results: dominant-language-medium (subtractive assimilatory submersion) 3.3. Somewhat better but not good enough results: early-exit transitional models 3.4. Even better results: late-exit transitional models 3.5. Strongest form: self-evident mother tongue medium models with no transition 4. Experiences from Nepal: the situation today 5. Specific challenges in Nepal: implementation strategies 5.1. -

Minority Languages in India

Thomas Benedikter Minority Languages in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India ---------------------------- EURASIA-Net Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues 2 Linguistic minorities in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India Bozen/Bolzano, March 2013 This study was originally written for the European Academy of Bolzano/Bozen (EURAC), Institute for Minority Rights, in the frame of the project Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues (EURASIA-Net). The publication is based on extensive research in eight Indian States, with the support of the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano and the Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata. EURASIA-Net Partners Accademia Europea Bolzano/Europäische Akademie Bozen (EURAC) – Bolzano/Bozen (Italy) Brunel University – West London (UK) Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität – Frankfurt am Main (Germany) Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group (India) South Asian Forum for Human Rights (Nepal) Democratic Commission of Human Development (Pakistan), and University of Dhaka (Bangladesh) Edited by © Thomas Benedikter 2013 Rights and permissions Copying and/or transmitting parts of this work without prior permission, may be a violation of applicable law. The publishers encourage dissemination of this publication and would be happy to grant permission. -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

Neo-Vernacularization of South Asian Languages

LLanguageanguage EEndangermentndangerment andand PPreservationreservation inin SSouthouth AAsiasia ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 7 Language Endangerment and Preservation in South Asia ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 7 PUBLISHED AS A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION LANGUAGE ENDANGERMENT AND PRESERVATION IN SOUTH ASIA Special Publication No. 7 (January 2014) ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 USA http:/nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I PRESS 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822-1888 USA © All text and images are copyright to the authors, 2014 Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives License ISBN 978-0-9856211-4-8 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4607 Contents Contributors iii Foreword 1 Hugo C. Cardoso 1 Death by other means: Neo-vernacularization of South Asian 3 languages E. Annamalai 2 Majority language death 19 Liudmila V. Khokhlova 3 Ahom and Tangsa: Case studies of language maintenance and 46 loss in North East India Stephen Morey 4 Script as a potential demarcator and stabilizer of languages in 78 South Asia Carmen Brandt 5 The lifecycle of Sri Lanka Malay 100 Umberto Ansaldo & Lisa Lim LANGUAGE ENDANGERMENT AND PRESERVATION IN SOUTH ASIA iii CONTRIBUTORS E. ANNAMALAI ([email protected]) is director emeritus of the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore (India). He was chair of Terralingua, a non-profit organization to promote bi-cultural diversity and a panel member of the Endangered Languages Documentation Project, London. -

Interference of Bhojpuri Language in Learning English As a Second Language

ELT VOICES – INDIA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR TEACHERS OF ENGLISH FEBRUARY 2014 | VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 | ISSN 2230-9136 (PRINT) 2321-7170 (ONLINE) Interference of Bhojpuri Language in Learning English as a Second Language V. RADHIKA1 ABSTRACT Studying the special features of any language is interesting for exploring many unrevealed facts about that language. The purpose of this paper is to create interest in the mind of readers to identify the special features of Bhojpuri language, which is gaining importance in India in the recent years among the spoken languages and make the readers to get rid of the problem of interference of this language in learning English as a second language. 1. Assistant Professor in English, AVIT, VMU, Paiyanoor, India. ELT VOICES – INDIA February 2014 | Volume 4, Issue 1 1. Introduction The paper proposes to make an in-depth study of Bhojpuri language to enable learners to compare and contrast between two languages, Bhojpuri and English by which communicative skill in English can be properly perceived. Bhojpuri language has its own phonological and morphological pattern. The present study is concerned with tracing the difference between two languages (i.e.) English and Bhojpuri, with reference to their grammatical structure and its relevant information. Aim of the Paper Create interest in the mind of scholars to make the detailed study about the Bhojpuri language with reference to their grammar pattern and to find out possible solution to eliminate the problem of mother tongue interference. 2. Origin of Bhojpuri Language Bhojpuri language gets its name from a place called ‘Bhojpur’ in Bihar. It is believed that Ujjain Rajputs claimed their descent from Raja Bhoj of Malwa in the sixteenth century. -

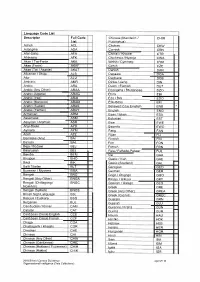

Language Code List Descriptor Full Code List Acholi ACL Adangme

Language Code List Descriptor Full Code Chinese (Mandarin I CHIM List Putonqhua) Acholi ACL Chokwe CKW Adangme ADA Cornish CRN Afar-Saha AFA Chitrali I Khowar CTR Afrikaans AFK Chichewa I Nyanja CWA Akan I Twi-Fante AKA Welsh I Cymraeg CYM Akan (Fante) AKAF Czech CZE Akan (Twi I Asante) AKAT Danish DAN Albanian I Shqip ALB Dagaare DGA Alur ALU Dagbane DGB Amharic AMR Dinka I Jieng DIN Arabic ARA Dutch I Flemish OUT Arabic (Any Other) ARAA Dzongkha I Bhutanese DZO Arabic (Algeria) ARAG Ebira EBI Arabic (Iraq) ARAI Eda I Bini EDO Arabic (Morocco) ARAM Efik-lbibio EFI Arabic (Sudan) ARAS Believed to be English ENB * Arabic (Yemen) ARAY English ENG * Armenian ARM Esan / lshan ESA Assamese ASM Estonian EST Assyrian I Aramaic ASR Ewe EWE Anyi-Baule AYB Ewondo EWO Aymara AYM Fang FAN Azeri AZE Fijian FIJ Bamileke (Any) BAI Finnish FIN Balochi BAL Fon FON Beja I Bedawi BEJ French FRN Belarusian BEL Fula I Fulfulde-Pulaar FUL Bemba BEM Ga GAA Bhojpuri BHO Gaelic / Irish GAE Bikol BIK Gaelic (Scotland) GAL Balti Tibetan BLT Georgian GEO Burmese I Myanma BMA German GER Bengali BNG Gago I Chigogo GGO Bengali (Any Other) BNGA Kikuyu I Gikuyu GKY Bengali (Chittagong I BNGC Galician I Galego GLG Noakhali) Greek GRE Bengali (Sylheti) BNGS Greek (Any Other) GREA British Sign Language BSL Greek (Cyprus) GREC Basque I Euskara BSQ Guarani GRN Bulgarian BUL Gujarati GUJ Cambodian I Khmer CAM Gurenne I Frafra GUN Catalan CAT Gurma GUR Caribbean Creole English CCE Hausa HAU Caribbean Creole French CCF Hindko HOK Chaga CGA Hebrew HEB Chattisgarhi I Khatahi CGR -

![Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2006 [FR191]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2463/nepal-demographic-and-health-survey-2006-fr191-1322463.webp)

Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2006 [FR191]

Nepal Demographic And Health Survey 2006 Population Division Ministry of Health and Population Government of Nepal Kathmandu, Nepal New ERA Kathmandu, Nepal Macro International Inc. Calverton, Maryland, U.S.A. May 2007 New ERA Ministry of Health and Population The 2006 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey (2006 NDHS) is part of the worldwide MEASURE DHS project, which is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under contract GPO-C-00- 03-00002-00. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Additional information about the 2006 NDHS may be obtained from Population Division, Ministry of Health and Population, Government of Nepal, Ramshahpath, Kathmandu, Nepal; Telephone: (977-1) 4262987; New ERA, P.O. Box 722, Kathmandu, Nepal; Telephone: (977-1) 4423176/4413603; Fax: (977-1) 4419562; E-mail: [email protected]. Additional information about the DHS project may be obtained from Macro International Inc., 11785 Beltsville Drive, Calverton, MD 20705 USA; Telephone: 301-572-0200, Fax: 301-572- 0999, E-mail: [email protected], Internet: http://www.measuredhs.com. Recommended citation: Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) [Nepal], New ERA, and Macro International Inc. 2007. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2006. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ministry of Health and Population, New ERA, and Macro International Inc. CONTENTS TABLES AND FIGURES ..........................................................................................................