Working Class Defence Organization, Anti-Fascist Resistance and the Arditi Del Popolo in Turin, 1919–22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

Lista Location English.Xlsx

LOCATIONS LIST Postal City Name Address Code ABANO TERME 35031 DIBRA KLODIANA VIA GASPARE GOZZI 3 ABBADIA SAN SALVATORE 53021 FABBRINI CARLO PIAZZA GRAMSCI 15 ABBIATEGRASSO 20081 BANCA DI LEGNANO VIA MENTANA ACCADIA 71021 NIGRO MADDALENA VIA ROMA 54 ACI CATENA 95022 PRINTEL DI STIMOLO PRINCIPATO VIA NIZZETI 43 ACIREALE 95024 LANZAFAME ALESSANDRA PIAZZA MARCONI 12 ACIREALE 95024 POLITI WALTER VIA DAFNICA 104 102 ACIREALE 95024 CERRA DONATELLA VIA VITTORIO EMANUELE 143 ACIREALE 95004 RIV 6 DI RIGANO ANGELA MARIA VIA VITTORIO EMANUELE II 69 ACQUAPENDENTE 01021 BONAMICI MANUELA VIA CESARE BATTISTI 1 ACQUASPARTA 05021 LAURETI ELISA VIA MARCONI 40 ACQUEDOLCI 98076 MAGGIORE VINCENZO VIA RICCA SALERNO 43 ACQUI TERME 15011 DOC SYSTEM VIA CARDINAL RAIMONDI 3 ACQUI TERME 15011 RATTO CLAUDIA VIA GARIBALDI 37 ACQUI TERME 15011 CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI ALESSAND CORSO BAGNI 102 106 ACQUI TERME 15011 CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI ALESSAND VIA AMENDOLA 31 ACRI 87041 MARCHESE GIUSEPPE ALDO MORO 284 ADRANO 95031 LA NAIA NICOLA VIA A SPAMPINATO 13 ADRANO 95031 SANTANGELO GIUSEPPA PIAZZA UMBERTO 8 ADRANO 95031 GIULIANO CARMELA PIAZZA SANT AGOSTINO 31 ADRIA 45011 ATTICA S R L RIVIERA GIACOMO MATTEOTTI 5 ADRIA 45011 SANTINI DAVIDE VIA CHIEPPARA 67 ADRIA 45011 FRANZOSO ENRICO CORSO GIUSEPPE MAZZINI 73 AFFI 37010 NIBANI DI PAVONE GIULIO AND C VIA DANZIA 1 D AGEROLA 80051 CUOMO SABATO VIA PRINCIPE DI PIEMONTE 11 AGIRA 94011 BIONDI ANTONINO PIAZZA F FEDELE 19 AGLIANO TERME 14041 TABACCHERIA DELLA VALLE VIA PRINCIPE AMEDEO 27 29 AGNA 35021 RIVENDITA N 7 VIA MURE 35 AGRIGENTO -

Chapter One: Introduction

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF IL DUCE TRACING POLITICAL TRENDS IN THE ITALIAN-AMERICAN MEDIA DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF FASCISM by Ryan J. Antonucci Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2013 Changing Perceptions of il Duce Tracing Political Trends in the Italian-American Media during the Early Years of Fascism Ryan J. Antonucci I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Ryan J. Antonucci, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Brian Bonhomme, Committee Member Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Carla Simonini, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Associate Dean of Graduate Studies Date Ryan J. Antonucci © 2013 iii ABSTRACT Scholars of Italian-American history have traditionally asserted that the ethnic community’s media during the 1920s and 1930s was pro-Fascist leaning. This thesis challenges that narrative by proving that moderate, and often ambivalent, opinions existed at one time, and the shift to a philo-Fascist position was an active process. Using a survey of six Italian-language sources from diverse cities during the inauguration of Benito Mussolini’s regime, research shows that interpretations varied significantly. One of the newspapers, Il Cittadino Italo-Americano (Youngstown, Ohio) is then used as a case study to better understand why events in Italy were interpreted in certain ways. -

Redalyc.Antonio Gramsci a Torino (1911-1922)

Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana ISSN: 1315-5216 [email protected] Universidad del Zulia Venezuela Maffia, Gesualdo Antonio Gramsci a Torino (1911-1922) Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, vol. 16, núm. 53, abril-junio, 2011, pp. 95-105 Universidad del Zulia Maracaibo, Venezuela Disponibile in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=27919220009 Come citare l'articolo Numero completo Sistema d'Informazione Scientifica Altro articolo Rete di Riviste Scientifiche dell'America Latina, i Caraibi, la Spagna e il Portogallo Home di rivista in redalyc.org Progetto accademico senza scopo di lucro, sviluppato sotto l'open acces initiative Antonio Gramsci in Turin (1911-1922) Gesualdo MAFFIA ipartimen to di Studi Politici, Universidad de Torino, Italia. La ciudad de Torino le ofrece a Antonio The city of Turin offered Antonio Gramsci un ambiente muy fecundo para su for- Gramsci a very fertile environment for his politi- mación política e intelectual, gracias a la presti- cal and intellectual development, thanks to its giosa tradición universitaria y a su rápido desa- prestigious university tradition and rapid indus- rrollo industrial. Gramsci, abandona sus estudios trial development. Gramsci abandonded his uni- universitarios, se dedica al periodismo político, versity studies and dedicated himself to political renovando la difusión del socialismo, ofrece un journalism, renewing the diffusion of socialism, ejemplo de periodismo crítico, atento a los he- offering an example of critical journalism, aware chos y a las contradicciones de la sociedad liberal -

Tra Fascismo Ed Antifascismo Nel Salernitano

TRA FASCISMO E ANTIFASCISMO NEL SALERNITANO di Ubaldo Baldi Dopo la “grande paura” della borghesia italiana del biennio rosso e la “grande speranza” per il proletariato della occupazione delle fabbriche del settembre 1920 , gli anni che vanno dal 1920 al 1923 , sono caratterizzati in Italia dalle aggressioni squadristiche fasciste. Queste hanno l’obiettivo di smantellare militarmente le sedi dei partiti e delle organizzazioni sindacali della sinistra e con una strategia del terrore eliminare fisicamente e moralmente le opposizioni. Una essenziale , ma non meno drammatica, esposizione di cifre e fatti di questo clima terroristico si ricava da quanto scritto in forma di denunzia da A. Gramsci nell’ “Ordine Nuovo” del 23.7.21 . Nel salernitano il fascismo si afferma, sia politicamente che militarmente, relativamente più tardi, sicuramente dopo la marcia su Roma. Questo fu solo in parte dovuto alla forza e al consistente radicamento all’interno del proletariato operaio delle sue rappresentanze sindacali e politiche. Di contro gli agrari e il padronato industriale ma anche la piccola borghesia , in linea con il classico trasformismo meridionale, prima di schierarsi apertamente , attesero il consolidamento del fascismo e il delinearsi preciso della sua natura per poi adeguarsi conformisticamente alla realtà politico-istituzionale che andava rappresentandosi come vincente. Anche perché ebbero ampiamente modo di verificare e valutare concretamente i privilegi e i vantaggi economici che il fascismo permetteva loro. Il quadro economico provinciale -

Europe in Crisis: Class 5 – the Rise of Fascism

Lecture Notes Europe in Crisis: Class 5 – The Rise of Fascism Slide 2 Postwar European Economies: • After the war, Europe suffered great economic problems. These problems varied from country to country. All countries had taken out loans to fight the war, and were trying to figure out how to pay those back. o England: Used to be a manufacturing powerhouse. Now, had lost many of its markets to foreign competitors like Japan and the US. Also, in 1914, England had risked falling behind Germany and the US technologically. This problem was exacerbated by a war that left Britain poor and the US rich. Economy falters, during the interwar period, Britain has a steady unemployment rate of about 10%. o France: Had taken out more loans than anyone else. Also, had to rebuild about a quarter of their country. Relied on German reparation payments for all this. Most people have work, though, because of jobs created by rebuilding. In 1923, when Germany defaults on reparations, France invades the Ruhr, and collects the profits from the coal mines here. An agreement is reached in 1924 with the Dawes Plan – American bankers promise to invest in Germany, thus boosting its economy, if France leaves the Ruhr, reduces reparations and agrees to a two-year moratorium. o Germany: Was reeling after the war, and had trouble getting its economy back on track. Problems were exacerbated when France invaded the Ruhr in 1923. Germany responded by encouraging workers to strike. Meanwhile, they kept printing money, trying to come up with a way to pay the French. -

Monitoraggio Gennaio 2021.Pdf

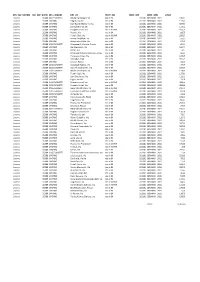

DES_IMP_DISTRIB COD_IMP_DISTRIB DES_COMUNE DES_VIA PARTE_IMP MESE_ISPE MESE_ISPE2 LUNGH Livorno 35389 COLLESALVETTI Alcide De Gasperi, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 108,54 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Fulgidi, Via dei rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 117,83 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Don David Albertario, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 659,93 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Carabinieri, Via dei rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 117,18 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Giorgio La Pira, Via rete in AP/MP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 185,25 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Rossini, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 68,70 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Fratelli Gigli, Via rete in AP/MP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 258,57 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Enrico Bartelloni, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 55,55 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Alessandro Volta, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 67,65 Livorno 35389 COLLESALVETTI Giuseppe Di Vittorio, Piazza rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 81,15 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO San Francesco, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 100,71 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Azzati, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 9,12 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Emanuele Filiberto di Savoia, Largo rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 66,16 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Francesco Crispi, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 127,26 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO D'Azeglio, Scali rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 301,29 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Cavour, Piazza rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 34,07 Livorno 35389 COLLESALVETTI Giuseppe Romita, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 37,79 Livorno 35389 COLLESALVETTI Niccolò Machiavelli, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 -

Amadeo Bordiga and the Myth of Antonio Gramsci

AMADEO BORDIGA AND THE MYTH OF ANTONIO GRAMSCI John Chiaradia PREFACE A fruitful contribution to the renaissance of Marxism requires a purely historical treatment of the twenties as a period of the revolutionary working class movement which is now entirely closed. This is the only way to make its experiences and lessons properly relevant to the essentially new phase of the present. Gyorgy Lukács, 1967 Marxism has been the greatest fantasy of our century. Leszek Kolakowski When I began this commentary, both the USSR and the PCI (the Italian Communist Party) had disappeared. Basing myself on earlier archival work and supplementary readings, I set out to show that the change signified by the rise of Antonio Gramsci to leadership (1924-1926) had, contrary to nearly all extant commentary on that event, a profoundly negative impact on Italian Communism. As a result and in time, the very essence of the party was drained, and it was derailed from its original intent, namely, that of class revolution. As a consequence of these changes, the party would play an altogether different role from the one it had been intended for. By way of evidence, my intention was to establish two points and draw the connecting straight line. They were: one, developments in the Soviet party; two, the tandem echo in the Italian party led by Gramsci, with the connecting line being the ideology and practices associated at the time with Stalin, which I label Center communism. Hence, from the time of Gramsci’s return from the USSR in 1924, there had been a parental relationship between the two parties. -

Dissertation Full Draft 06 01 18

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO “Nothing is Going to be Named After You”: Ethical Citizenship Among Citizen Activists in Bosnia-Herzegovina A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Natasa Garic-Humphrey Committee in charge: Professor Nancy Postero, Chair Professor Joseph Hankins Professor Martha Lampland Professor Patrick Patterson Professor Saiba Varma 2018 Copyright Natasa Garic-Humphrey, 2018 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Natasa Garic-Humphrey is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ Chair University of California San Diego 2018 iii To: My mom and dad, who supported me unselfishly. My Clinton and Alina, who loved me unconditionally. My Bosnian family and friends, who shared with me their knowledge. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ...................................................................................................................... iii Dedication ............................................................................................................................. iv Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................v -

Workers' Demonstrations and Liberals

Workers’ Demonstrations and Liberals’ Condemnations: the Italian Liberal Press’s Coverage of General Strikes, Factory Occupations, and Workers’ Self-Defense Groups during the Rise of Fascism, 1919-1922 By Ararat Gocmen, Princeton University Workers occupying a Turin factory in September 1920. “Torino - Comizio festivo in una officina metallurgica occupata.” L’Illustrazione italiana, 26 September 1920, p. 393 This paper outlines the evolution of the Italian liberal press’s in the liberal press in this way, it illustrates how working-class coverage of workers’ demonstrations from 1919 to 1922. The goal radicalism contributed to the rise of fascism in Italy.1 is to show that the Italian liberal middle classes became increas- ingly philofascistic in response to the persistency of workers’ dem- onstrations during this period. The paper analyzes articles from 1 I would like to thank Professor Joseph Fronczak for his guidance the Italian newspapers La Stampa and L’Illustrazione italiana, in writing this paper, especially for his recommended selections treating their coverage of general strikes, factory occupations, and from the existing historiography of Italian fascism that I cite workers’ self-defense groups as proxies for middle-class liberals’ throughout. I am also grateful to Professors Pietro Frassica and interpretations of workers’ demonstrations. By tracking changes Fiorenza Weinapple for instructing me in the Italian language 29 Historians of Italian fascism often divide the years lead- workers’ demonstrations took place during the working-class ing up to the fascists’ rise to power—from the immediate mobilization of 1919-1920, strikes—sometimes even large aftermath of the First World War at the beginning of 1919 to ones—remained a persistent phenomenon in the two years Benito Mussolini’s March on Rome in October 1922—into of violent fascist reaction that followed.7 Additionally, while two periods. -

Reclaiming Their Shadow: Ethnopolitical Mobilization in Consolidated Democracies

Reclaiming their Shadow: Ethnopolitical Mobilization in Consolidated Democracies Ph. D. Dissertation by Britt Cartrite Department of Political Science University of Colorado at Boulder May 1, 2003 Dissertation Committee: Professor William Safran, Chair; Professor James Scarritt; Professor Sven Steinmo; Associate Professor David Leblang; Professor Luis Moreno. Abstract: In recent decades Western Europe has seen a dramatic increase in the political activity of ethnic groups demanding special institutional provisions to preserve their distinct identity. This mobilization represents the relative failure of centuries of assimilationist policies among some of the oldest nation-states and an unexpected outcome for scholars of modernization and nation-building. In its wake, the phenomenon generated a significant scholarship attempting to account for this activity, much of which focused on differences in economic growth as the root cause of ethnic activism. However, some scholars find these models to be based on too short a timeframe for a rich understanding of the phenomenon or too narrowly focused on material interests at the expense of considering institutions, culture, and psychology. In response to this broader debate, this study explores fifteen ethnic groups in three countries (France, Spain, and the United Kingdom) over the last two centuries as well as factoring in changes in Western European thought and institutions more broadly, all in an attempt to build a richer understanding of ethnic mobilization. Furthermore, by including all “national -

Fascism Rises in Europe

3 Fascism Rises in Europe MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES POWER AND AUTHORITY In These dictators changed the •fascism •Nazism response to political turmoil and course of history, and the world • Benito • Mein Kampf economic crises, Italy and is still recovering from their Mussolini • lebensraum Germany turned to totalitarian abuse of power. • Adolf Hitler dictators. SETTING THE STAGE Many democracies, including the United States, Britain, and France, remained strong despite the economic crisis caused by the Great Depression. However, millions of people lost faith in democratic govern- ment. In response, they turned to an extreme system of government called fas- cism. Fascists promised to revive the economy, punish those responsible for hard times, and restore order and national pride. Their message attracted many people who felt frustrated and angered by the peace treaties that followed World War I and by the Great Depression. TAKING NOTES Fascism’s Rise in Italy Comparing and Contrasting Use a chart Fascism (FASH•IHZ•uhm) was a new, militant political movement that empha- to compare Mussolini's sized loyalty to the state and obedience to its leader. Unlike communism, fascism rise to power and his had no clearly defined theory or program. Nevertheless, most Fascists shared goals with Hitler's. several ideas. They preached an extreme form of nationalism, or loyalty to one’s country. Fascists believed that nations must struggle—peaceful states were Hitler Mussolini doomed to be conquered. They pledged loyalty to an authoritarian leader who Rise: Rise: guided and brought order to the state. In each nation, Fascists wore uniforms of a certain color, used special salutes, and held mass rallies.