The Decipherment of Ancient Maya Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

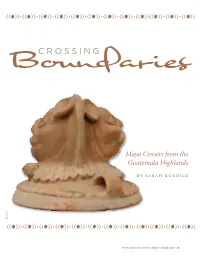

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

Manufactured Light Mirrors in the Mesoamerican Realm

Edited by Emiliano Gallaga M. and Marc G. Blainey MANUFACTURED MIRRORS IN THE LIGHT MESOAMERICAN REALM COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables xiii Chapter 1: Introduction Emiliano Gallaga M. 3 Chapter 2: How to Make a Pyrite Mirror: An Experimental Archaeology Project Emiliano Gallaga M. 25 Chapter 3: Manufacturing Techniques of Pyrite Inlays in Mesoamerica Emiliano Melgar, Emiliano Gallaga M., and Reyna Solis 51 Chapter 4: Domestic Production of Pyrite Mirrors at Cancuén,COPYRIGHTED Guatemala MATERIAL Brigitte KovacevichNOT FOR DISTRIBUTION73 Chapter 5: Identification and Use of Pyrite and Hematite at Teotihuacan Julie Gazzola, Sergio Gómez Chávez, and Thomas Calligaro 107 Chapter 6: On How Mirrors Would Have Been Employed in the Ancient Americas José J. Lunazzi 125 Chapter 7: Iron Pyrite Ornaments from Middle Formative Contexts in the Mascota Valley of Jalisco, Mexico: Description, Mesoamerican Relationships, and Probable Symbolic Significance Joseph B. Mountjoy 143 Chapter 8: Pre-Hispanic Iron-Ore Mirrors and Mosaics from Zacatecas Achim Lelgemann 161 Chapter 9: Techniques of Luminosity: Iron-Ore Mirrors and Entheogenic Shamanism among the Ancient Maya Marc G. Blainey 179 Chapter 10: Stones of Light: The Use of Crystals in Maya Divination John J. McGraw 207 Chapter 11: Reflecting on Exchange: Ancient Maya Mirrors beyond the Southeast Periphery Carrie L. Dennett and Marc G. Blainey 229 Chapter 12: Ritual Uses of Mirrors by the Wixaritari (Huichol Indians): Instruments of Reflexivity in Creative Processes COPYRIGHTEDOlivia Kindl MATERIAL 255 NOTChapter FOR 13: Through DISTRIBUTION a Glass, Brightly: Recent Investigations Concerning Mirrors and Scrying in Ancient and Contemporary Mesoamerica Karl Taube 285 List of Contributors 315 Index 317 vi contents 1 “Here is the Mirror of Galadriel,” she said. -

The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the Cult of Sacred War at Teotihuacan

The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the cult of sacred war at Teotihuacan KARLA. TAUBE The Temple of Quetzalcoatl at Teotihuacan has been warrior elements found in the Maya region also appear the source of startling archaeological discoveries since among the Classic Zapotee of Oaxaca. Finally, using the early portion of this century. Beginning in 1918, ethnohistoric data pertaining to the Aztec, Iwill discuss excavations by Manuel Gamio revealed an elaborate the possible ethos surrounding the Teotihuacan cult and beautifully preserved facade underlying later of war. construction. Although excavations were performed intermittently during the subsequent decades, some of The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the Tezcacoac the most important discoveries have occurred during the last several years. Recent investigations have Located in the rear center of the great Ciudadela revealed mass dedicatory burials in the foundations of compound, the Temple of Quetzalcoatl is one of the the Temple of Quetzalcoatl (Sugiyama 1989; Cabrera, largest pyramidal structures at Teotihuacan. In volume, Sugiyama, and Cowgill 1988); at the time of this it ranks only third after the Pyramid of the Moon and writing, more than eighty individuals have been the Pyramid of the Sun (Cowgill 1983: 322). As a result discovered interred in the foundations of the pyramid. of the Teotihuacan Mapping Project, it is now known Sugiyama (1989) persuasively argues that many of the that the Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the enclosing individuals appear to be either warriors or dressed in Ciudadela are located in the center of the ancient city the office of war. (Mill?n 1976: 236). The Ciudadela iswidely considered The archaeological investigations by Cabrera, to have been the seat of Teotihuacan rulership, and Sugiyama, and Cowgill are ongoing, and to comment held the palaces of the principal Teotihuacan lords extensively on the implications of their work would be (e.g., Armillas 1964: 307; Mill?n 1973: 55; Coe 1981: both premature and presumptuous. -

Breaking the Maya Code : Michael D. Coe Interview (Night Fire Films)

BREAKING THE MAYA CODE Transcript of filmed interview Complete interview transcripts at www.nightfirefilms.org MICHAEL D. COE Interviewed April 6 and 7, 2005 at his home in New Haven, Connecticut In the 1950s archaeologist Michael Coe was one of the pioneering investigators of the Olmec Civilization. He later made major contributions to Maya epigraphy and iconography. In more recent years he has studied the Khmer civilization of Cambodia. He is the Charles J. MacCurdy Professor of Anthropology, Emeritus at Yale University, and Curator Emeritus of the Anthropology collection of Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. He is the author of Breaking the Maya Code and numerous other books including The Maya Scribe and His World, The Maya and Angkor and the Khmer Civilization. In this interview he discusses: The nature of writing systems The origin of Maya writing The role of writing and scribes in Maya culture The status of Maya writing at the time of the Spanish conquest The impact for good and ill of Bishop Landa The persistence of scribal activity in the books of Chilam Balam and the Caste War Letters Early exploration in the Maya region and early publication of Maya texts The work of Constantine Rafinesque, Stephens and Catherwood, de Bourbourg, Ernst Förstemann, and Alfred Maudslay The Maya Corpus Project Cyrus Thomas Sylvanus Morley and the Carnegie Projects Eric Thompson Hermann Beyer Yuri Knorosov Tania Proskouriakoff His own early involvement with study of the Maya and the Olmec His personal relationship with Yuri -

Reassessing Shamanism and Animism in the Art and Archaeology of Ancient Mesoamerica

religions Article Reassessing Shamanism and Animism in the Art and Archaeology of Ancient Mesoamerica Eleanor Harrison-Buck 1,* and David A. Freidel 2 1 Department of Anthropology, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03824, USA 2 Department of Anthropology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63105, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Shamanism and animism have proven to be useful cross-cultural analytical tools for anthropology, particularly in religious studies. However, both concepts root in reductionist, social evolutionary theory and have been criticized for their vague and homogenizing rubric, an overly romanticized idealism, and the tendency to ‘other’ nonwestern peoples as ahistorical, apolitical, and irrational. The alternative has been a largely secular view of religion, favoring materialist processes of rationalization and “disenchantment.” Like any cross-cultural frame of reference, such terms are only informative when explicitly defined in local contexts using specific case studies. Here, we consider shamanism and animism in terms of ethnographic and archaeological evidence from Mesoamerica. We trace the intellectual history of these concepts and reassess shamanism and animism from a relational or ontological perspective, concluding that these terms are best understood as distinct ways of knowing the world and acquiring knowledge. We examine specific archaeological examples of masked spirit impersonations, as well as mirrors and other reflective materials used in divination. We consider not only the productive and affective energies of these enchanted materials, but also the Citation: Harrison-Buck, Eleanor, potentially dangerous, negative, or contested aspects of vital matter wielded in divinatory practices. and David A. Freidel. 2021. Reassessing Shamanism and Keywords: Mesoamerica; art and archaeology; shamanism; animism; Indigenous ontology; relational Animism in the Art and Archaeology theory; divination; spirit impersonation; material agency of Ancient Mesoamerica. -

Evenings for Educators 2017–18

^ Education Department Evenings for Educators Los Angeles County Museum of Art 5905 Wilshire Boulevard 2017–18 Los Angeles, California 90036 Resources Books for Students Online Resources Corn Is Maize: The Gift of the Indians Art of the Ancient Americas at LACMA Aliki Browse LACMA’s diverse collection of artwork from This book tells the story of how Native American the ancient Americas by time period or object type. farmers thousands of years ago found and nourished collections.lacma.org (Curatorial area/Art of the a wild grass plant and made corn an important part Ancient Americas) of their lives. Grades K–3 Digital Stories—Teotihuacan: City of Water, Descifrar el Cielo: La Astronomía en City of Fire Mesoamérica The de Young Museum in San Francisco created Federico Guzmán an online introduction to Teotihuacan that includes This Spanish-language book describes how the numerous images and maps of the city. Native communities of Mexico and Central America https://digitalstories.famsf.org/teo#start used their observations of the sky to develop agriculture, a precise calendar system, and advanced Related Curriculum Materials civilizations. Grades 6–12 Evenings for Educators resources include illustrated Here Is My Kingdom: Hispanic-American essays, discussion prompts for the classroom, Literature and Art for Young People and lesson plans for art-making activities. Browse Edited by Charles Sullivan selected online curriculum at lacma.org/students- Explore the multifaceted Hispanic-American/Latino teachers/teacher-resources. experience in this colorful anthology of poems, prose, and visual art. Grades K–12 Relevant curriculum materials include: Books for Teachers • Ancient Mexico: The Legacy of the Plumed Serpent • Olmec: Masterworks of Ancient Mexico An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya Mary Ellen Miller and Karl Taube Containing nearly 300 entries, this illustrated dictionary describes the mythology and religion of Mesoamerican cultures. -

The 2019 Mesoamerica Meetings Dress Codes

DRESS CODES Regalia and Attire in Ancient Mesoamerica The 2019 Mesoamerica Meetings Dress Codes: Regalia and Attire in Ancient Mesoamerica SYMPOSIUM January 18–19, 2019 Art Building Auditorium (ART 1.102) The University of Texas at Austin SCHEDULE SCHEDULE THURSDAY — KEYNOTE 6:00 The Roots of Attire and Regalia: Fibers, Dyestuffs, SATURDAY and Weaving Techniques in Mesoamerica Alejandro de Ávila 9:00 Ancient Maya Ear, Nose, 1:30 Classic Maya Dress: Wrapping and Lip Decorations in Body, Language and Culture Art and Archaeology Dicey Taylor Nicholas Carter 2:10 Of Solar Rays and FRIDAY 9:40 Emulation is the Sincerest Eagle Feathers: Form of Flattery: Gulf Coast New Understandings of 8:45 Welcome 1:30 The Ecological Logic of Aztec Olmec Costume in the Maya Headdresses in Teotihuacan David Stuart Royal Attire: Dressing to San Bartolo Murals Jesper Nielsen Express Dominion Billie J. A. Follensbee Christophe Helmke 9:00 Logographic Depictions Lois Martin of Mesoamerican Clothing 10:20 Coffee Break 2:50 The Human Part of the Marc Zender 2:10 Costume and the Case of Animal: Reflections on Hybrid Mixtecan Identity 10:40 ‘Men turned into the image of and Anthropomorphic Images 9:40 Beyond Physicality: Dress, Geoffrey G. McCafferty the devil himself!’ (Fray Diego of the Feathered Serpent Agency and Social Becoming Sharisse McCafferty Durán) Aztec Priests’ Attire Ángel González in the Nahua World and Attributes Bertrand Lobjois Justyna Olko 2:50 Regalia and Political Sylvie Peperstraete Communication among the 3:30 Coffee Break 10:20 Coffee Break Classic Maya 11:20 Ancient Maya Courtly Dress Maxime Lamoureux-St-Hilaire Cara G. -

Archaeological Reconnaissance in the Upper Río El Tambor, Guatemala

FAMSI © 2005: Karl Taube, Zachary Hruby and Luis Romero Jadeite Sources and Ancient Workshops: Archaeological Reconnaissance in the Upper Río El Tambor, Guatemala Research Year: 2004 Culture: Maya Chronology: Late Classic Location: Central Motagua Valley, Guatemala Sites: Río El Tambor Region Table of Contents Introduction Sitio Aguilucho Terrace 1 Terrace 2 Terrace 3 Terrace 4 Sitio Cerro Chucunhueso Sitio Carrizal Grande Los Encuentros 1 & 2 Sitio La Ceiba Site Composition and Distribution Obsidian Conclusions Acknowledgments List of Figures Sources Cited Appendix: Jade Samples from the Motagua Region Submitted 01/18/2005 by: Karl Taube Dept. of Anthropology, U.C. Riverside [email protected] Introduction Since the first documentation of jade sources by Robert Leslie at Manzanotal in 1952, it has been known that the Central Motagua Valley of Guatemala is an important jadeite-bearing region (Foshag and Leslie 1955). Today, large amounts of jadeite are being collected from a number of sources on the northern side of the Motagua River, including the lower Río La Palmilla and areas in the vicinity of Río Hondo (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5; and Appendix, Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). Most of this material is transported to the city of Antigua, where it is carved into jewelry and sculpture for the tourist trade. Figure 1. Map of Central Motagua Valley, including Río Blanco and Río El Tambor tributaries (from Seitz et al. 2001). 2 Figure 2. View of Río La Palmilla in foreground and Motagua Valley in distance. 3 Figure 3. Lower Río La Palmilla, many of the boulders visible are of jadeite. -

Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks

Pre-Columbian Art at Dumbarton Oaks, No. 2 OLMEC ART AT DUMBARTON OAKS OLMEC ART AT DUMBARTON OAKS Karl A. Taube Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. Copyright © 2004 by Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C. Library of Congress Cataloging-in Publication Data to come To the memory of Carol Callaway, Alba Guadalupe Mastache, Linda Schele, and my sister, Marianna Taube—four who fought the good fight CONTENTS PREFACE Jeffrey Quilter ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi List of Plates xii List of Figures xiii Chronological Chart of Mesoamerica xv Maps xvi INTRODUCTION: THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF OLMEC RESEARCH 1 THE DUMBARTON OAKS COLLECTION 49 BIBLIOGRAPHY 185 APPENDIX 203 INDEX 221 Preface lmec art held a special place in the heart of Robert Woods Bliss, who built the collection now housed at Dumbarton Oaks and who, with his wife, Mildred, conveyed the gar- Odens, grounds, buildings, library, and collections to Harvard University. The first object he purchased, in 1912, was an Olmec statuette (Pl. 8); he commonly carried a carved jade in his pocket; and, during his final illness, it was an Olmec mask (Pl. 30) that he asked to be hung on the wall of his sick room. It is easy to understand Bliss’s predilection for Olmec art. With his strong preference for metals and polished stone, the Olmec jades were particularly appealing to him. Although the finest Olmec ceramics are masterpieces in their own right, he preferred to concen- trate his collecting on jades. As Karl Taube discusses in detail in this volume of Pre-Columbian Art at Dumbarton Oaks, Olmec jades are the most beautiful stones worked in Mesoamerica. -

Interpreting Tepantitla Patio 2 Mural (Teotihuacan, Mexico)

INTERPRETING TEPANTITLA PATIO 2 MURAL (TEOTIHUACAN, MEXICO) AS AN ANCESTRAL FIGURE ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts In Art History ____________ by © Atalie Tate Halpin Fall 2018 INTERPRETING TEPANTITLA PATIO 2 MURAL (TEOTIHUACAN, MEXICO) AS AN ANCESTRAL FIGURE A Thesis by Atalie Tate Halpin APPROVED BY THE INTERIM DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES: ______________________________ Sharon Barrios, PhD. APPROVED THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: ______________________________ ______________________________ Asa S. Mittman, PhD., Chair Matthew G. Looper, PhD. Graduate Coordinator ______________________________ Rachel Middleman, PhD. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………….. iv CHAPTER PAGE I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 II. Tepantitla Patio 2 Mural: Context and Description .......................................................... 4 III. Previous Interpretations: Literature Review …………………………………………… 14 A. “Tlaloc”……………………………………………………………………………... 14 B. “Great Goddess” …………………………………………………………………… 15 C. “Spider Woman” …………………………………………………………………… 18 D. “Water Goddess” and Other Interpretations ……………………………………….. 19 IV. Methods ………………………………………………………………………………... 24 A. Iconography ………………………………………………………………………... 24 B. Cross-cultural and Trans-historical Comparisons …………………………………. 25 V. Iconographic Analysis …………………………………………………………………… 29 A. World Trees and the Cosmic Center ………………………………………………. -

60 the Identification of the West Wall Figures at Pinturas Sub-1, San

60 THE IDENTIFICATION OF THE WEST WALL FIGURES AT PINTURAS SUB-1, SAN BARTOLO, PETÉN William A. Saturno David Stuart Karl Taube Keywords: Maya archaeology, Guatemala, Petén, San Bartolo, mural painting, iconography, deities, Late Preclassic period The magnificent mural paintings remarkably preserved inside the chamber of Pinturas Sub-1, in Guatemala, show promise to be one of the most significant archaeological findings in the Maya region. The paintings unfold a minute portrait of the Maya mythology of creation, and an exceptional antiquity, as they date to century I BC. During the 2003 field season, the mural on the North Wall of Pinturas Sub-1 was exposed, and the interpretation of the scenes presented (Taube et al. 2004; Saturno and Taube 2004). This study is focused on the results of the 2004 excavations conducted on the West Wall of the chamber in Pinturas Sub-1. Alike the North Wall, a numeric system was used, and the varied images present in the mural from left to right, and from its upper portion to its base, were labeled. Like there are missing areas in the West Wall, as is the case with the characteristics of image 11 which were not fully identified, it was assigned the letter “P” in the sequence, which defines it as being of a provisional nature; consequently, there are other figures in a similar situation. Clearly, a good number of the interpretations could change at the light of subsequent reconstructions. The south half of the West Wall represents the raising of five trees of life in a context of sacrificial offerings which include ritual bloodletting.