Archaeological Reconnaissance in the Upper Río El Tambor, Guatemala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROSARIO & HUNTER (ACARINA: TRIGYNASPIDA: Klinckowstroemildae)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Entomology Papers from Other Sources Entomology Collections, Miscellaneous 1994 KLINCKOWSTROEMIA MULTISETILLOSA ROSARIO & HUNTER (ACARINA: TRIGYNASPIDA: KLiNCKOWSTROEMIlDAE) ASSOCIATED WITH THREE SPECIES OF PROCULUS KUWERT(COLEOPTERA: PASSALIDAE) Elcidia Emely Padilla Universidad de Valle de Guatemala Jack C. Schuster Universidad del Valle de Guatemala, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entomologyother Padilla, Elcidia Emely and Schuster, Jack C., "KLINCKOWSTROEMIA MULTISETILLOSA ROSARIO & HUNTER (ACARINA: TRIGYNASPIDA: KLiNCKOWSTROEMIlDAE) ASSOCIATED WITH THREE SPECIES OF PROCULUS KUWERT(COLEOPTERA: PASSALIDAE)" (1994). Entomology Papers from Other Sources. 153. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entomologyother/153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology Collections, Miscellaneous at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Entomology Papers from Other Sources by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ACli1 ZO(l/. Ml!x. /n ..~.) 61: 1·5 (799-11 KLINCKOWSTROEMIA MUL TISETILLOSA ROSARIO & HUNTER (ACARINA: TRIGYNASPIDA: KLiNCKOWSTROEMIlDAE) ASSOCIATED WITH THREE SPECIES OF PROCULUS KUWERT (COLEOPTERA: PASSALIDAE) Elcidia Emely Padilla and Jack Schuster Systematic Entomology Laboratory Research Institute 1-310 Universidad del Valle de Guatemala Apartado Postal /I 82 Guatemala 01901. GUATEMALA. C. A. ABSTRACT KJinckowstroemia rnti/ltSelll/osa Rosario Be Hunter was known to be asociated with Proeu/IJs mfl/s.-cclll Kaup In Guatemala. We have found K. fTI[lltiseril/osa associated wilh illiopatric populations of P. burmOlsteriKuwert and P. opacipennis (Thompsonl. K. mlJ/rlsertl/f)sa is now known from 4 regions of Guatemala alld 1 of Honduras. At prosent. Ihere appears 10 be no gene flow between thesn 5 ilreas. -

List of Rivers of Honduras

Sl.No River Name Draining Into Comments 1 Negro River Caribbean Sea Borders Nicaragua. (Central America) 2 Coco River (Segovia River) Caribbean Sea Borders Nicaragua. 3 Cruta River Caribbean Sea 4 Nakunta River Caribbean Sea 5 Mocorón River Caribbean Sea 6 Warunta River Caribbean Sea 7 Patuca River Caribbean Sea is the largest in Honduras and the second largest in Central America. 8 Wampú River Caribbean Sea 9 Río Gualcarque Caribbean Sea 10 Guayambre River Caribbean Sea 11 Guayape River Caribbean Sea 12 Tinto River Caribbean Sea 13 Talgua River Caribbean Sea 14 Telica River Caribbean Sea 15 Jalan River Caribbean Sea 16 Sigre River Caribbean Sea 17 Plátano River Caribbean Sea 18 Río Sico Tinto Negro (Tinto River) Caribbean Sea 19 Sico River Caribbean Sea 20 Paulaya River Caribbean Sea 21 Aguán River Caribbean Sea 22 Yaguala River (Mangulile River) Caribbean Sea 23 Papaloteca River Caribbean Sea 24 Cangrejal River Caribbean Sea 25 Danto River Caribbean Sea 26 Cuero River Caribbean Sea 27 Leán River Caribbean Sea 28 Tela River Caribbean Sea 29 Ulúa River Caribbean Sea Is the most important river economically. 30 Humuya River Caribbean Sea 31 Sulaco River Caribbean Sea 32 Blanco River Caribbean Sea 33 Otoro River (Río Grande de Otoro) Caribbean Sea 34 Jicatuyo River Caribbean Sea 35 Higuito River Caribbean Sea 36 Chamelecón River Caribbean Sea 37 Motagua River Caribbean Sea 38 Choluteca River Pacific Ocean 39 Goascorán River Pacific Ocean Divides El Salvador from Honduras. 40 Guarajambala River Pacific Ocean 41 Lempa River Pacific Ocean 42 Mocal River Pacific Ocean 43 Nacaome River Pacific Ocean 44 Petacon River Pacific Ocean 45 Azacualpa River Pacific Ocean 46 De la Sonta River Pacific Ocean 47 Negro River Pacific Ocean 48 Sumpul River Pacific Ocean 49 Torola River Pacific Ocean For more information kindly visit : www.downloadexcelfiles.com www.downloadexcelfiles.com. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

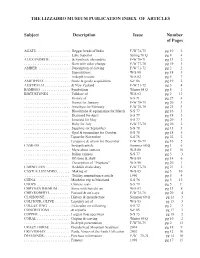

List of Articles

THE LIZZADRO MUSEUM PUBLICATION INDEX OF ARTICLES Subject Description Issue Number of Pages AGATE. .. Beggar beads of India F-W 74-75 pg 10 2 . Lake Superior Spring 70 Q pg 8 4 ALEXANDRITE . & Synthetic alexandrite F-W 70-71 pg 13 2 . Gem with color change F-W 77-78 pg 19 1 AMBER . Description of carving F-W 71-72 pg 2 2 . Superstitions W-S 80 pg 18 5 . in depth treatise W-S 82 pg 5 7 AMETHYST . Stone & geode acquisitions S-F 86 pg 19 2 AUSTRALIA . & New Zealand F-W 71-72 pg 3 4 BAMBOO . Symbolism Winter 68 Q pg 8 1 BIRTHSTONES . Folklore of W-S 93 pg 2 13 . History of S-S 71 pg 27 4 . Garnet for January F-W 78-79 pg 20 3 . Amethyst for February F-W 78-79 pg 22 3 . Bloodstone & aquamarine for March S-S 77 pg 16 3 . Diamond for April S-S 77 pg 18 3 . Emerald for May S-S 77 pg 20 3 . Ruby for July F-W 77-78 pg 20 2 . Sapphire for September S-S 78 pg 15 3 . Opal & tourmaline for October S-S 78 pg 18 5 . Topaz for November S-S 78 pg 22 2 . Turquoise & zircon for December F-W 78-79 pg 16 5 CAMEOS . In-depth article Summer 68 Q pg 1 6 . More about cameos W-S 80 pg 5 10 . Italian cameos S-S 77 pg 3 3 . Of stone & shell W-S 89 pg 14 6 . Description of “Neptune” W-S 90 pg 20 1 CARNELIAN . -

DECISION TIME for CLOUD FORESTS No

WATER-RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS OF THE HUMID TROPICS AND OTHER WARM HUMID REGIONS IHP HUMID TROPICS PROGRAMME SERIES NO. 13 IHP Humid Tropics Programme Series No. 1 The Disappearing Tropical Forests DECISION TIME FOR CLOUD FORESTS No. 2 Small Tropical Islands No. 3 Water and Health No. 4 Tropical Cities: Managing their Water No. 5: Integrated Water Resource Management No. 6 Women in the Humid Tropics No. 7 Environmental Impacts of Logging Moist Tropical Forests No. 8 Groundwater No. 9 Reservoirs in the Tropics – A Matter of Balance No.10 Environmental Impacts of Converting Moist Tropical Forest to Agriculture and Plantations No.11 Helping Children in the Humid Tropics: Water Education No.12 Wetlands in the Humid Tropics No.13 Decision Time for Cloud Forests For further information on this Series, contact: UNESCO Division of Water Sciences International Hydrological Programme 1, Rue Miollis 75352 Paris 07 SP France tel. (+33) 1 45 68 40 02 fax (+33) 1 45 67 58 69 PREFACE At a Tropical Montane Cloud Forest workshop held at Cambridge, U.K. in July 1998, 30 scientists, professional managers, and NGO conservation group members representing more than 14 countries and all global regions, concluded that there is insufficient public and political awareness of the status and values of Tropical Montane Cloud Forests (TMCF). The group suggested that a science-based “pop-doc” would be an effective initial action to remedy this. What follows is a response to that recommendation. It documents some of the scientific information that will be of interest to other scientists and managers of TMCF, but not over- whelming for a lay reader who is seeking to become more informed about these remarkable ecosystems. -

A Mat of Serpents: Aztec Strategies of Control from an Empire in Decline

A Mat of Serpents: Aztec Strategies of Control from an Empire in Decline Jerónimo Reyes On my honor, Professors Andrea Lepage and Elliot King mark the only aid to this thesis. “… the ruler sits on the serpent mat, and the crown and the skull in front of him indicate… that if he maintained his place on the mat, the reward was rulership, and if he lost control, the result was death.” - Aztec rulership metaphor1 1 Emily Umberger, " The Metaphorical Underpinnings of Aztec History: The Case of the 1473 Civil War," Ancient Mesoamerica 18, 1 (2007): 18. I dedicate this thesis to my mom, my sister, and my brother for teaching me what family is, to Professor Andrea Lepage for helping me learn about my people, to Professors George Bent, and Melissa Kerin for giving me the words necessary to find my voice, and to everyone and anyone finding their identity within the self and the other. Table of Contents List of Illustrations ………………………………………………………………… page 5 Introduction: Threads Become Tapestry ………………………………………… page 6 Chapter I: The Sum of its Parts ………………………………………………… page 15 Chapter II: Commodification ………………………………………………… page 25 Commodification of History ………………………………………… page 28 Commodification of Religion ………………………………………… page 34 Commodification of the People ………………………………………… page 44 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………... page 53 Illustrations ……………………………………………………………………... page 54 Appendices ……………………………………………………………………... page 58 Bibliography ……………………………………………………………………... page 60 …. List of Illustrations Figure 1: Statue of Coatlicue, Late Period, 1439 (disputed) Figure 2: Peasant Ritual Figurines, Date Unknown Figure 3: Tula Warrior Figure Figure 4: Mexica copy of Tula Warrior Figure, Late Aztec Period Figure 5: Coyolxauhqui Stone, Late Aztec Period, 1473 Figure 6: Male Coyolxauhqui, carving on greenstone pendant, found in cache beneath the Coyolxauhqui Stone, Date Unknown Figure 7: Vessel with Tezcatlipoca Relief, Late Aztec Period, ca. -

Manufactured Light Mirrors in the Mesoamerican Realm

Edited by Emiliano Gallaga M. and Marc G. Blainey MANUFACTURED MIRRORS IN THE LIGHT MESOAMERICAN REALM COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables xiii Chapter 1: Introduction Emiliano Gallaga M. 3 Chapter 2: How to Make a Pyrite Mirror: An Experimental Archaeology Project Emiliano Gallaga M. 25 Chapter 3: Manufacturing Techniques of Pyrite Inlays in Mesoamerica Emiliano Melgar, Emiliano Gallaga M., and Reyna Solis 51 Chapter 4: Domestic Production of Pyrite Mirrors at Cancuén,COPYRIGHTED Guatemala MATERIAL Brigitte KovacevichNOT FOR DISTRIBUTION73 Chapter 5: Identification and Use of Pyrite and Hematite at Teotihuacan Julie Gazzola, Sergio Gómez Chávez, and Thomas Calligaro 107 Chapter 6: On How Mirrors Would Have Been Employed in the Ancient Americas José J. Lunazzi 125 Chapter 7: Iron Pyrite Ornaments from Middle Formative Contexts in the Mascota Valley of Jalisco, Mexico: Description, Mesoamerican Relationships, and Probable Symbolic Significance Joseph B. Mountjoy 143 Chapter 8: Pre-Hispanic Iron-Ore Mirrors and Mosaics from Zacatecas Achim Lelgemann 161 Chapter 9: Techniques of Luminosity: Iron-Ore Mirrors and Entheogenic Shamanism among the Ancient Maya Marc G. Blainey 179 Chapter 10: Stones of Light: The Use of Crystals in Maya Divination John J. McGraw 207 Chapter 11: Reflecting on Exchange: Ancient Maya Mirrors beyond the Southeast Periphery Carrie L. Dennett and Marc G. Blainey 229 Chapter 12: Ritual Uses of Mirrors by the Wixaritari (Huichol Indians): Instruments of Reflexivity in Creative Processes COPYRIGHTEDOlivia Kindl MATERIAL 255 NOTChapter FOR 13: Through DISTRIBUTION a Glass, Brightly: Recent Investigations Concerning Mirrors and Scrying in Ancient and Contemporary Mesoamerica Karl Taube 285 List of Contributors 315 Index 317 vi contents 1 “Here is the Mirror of Galadriel,” she said. -

The Bilimek Pulque Vessel (From in His Argument for the Tentative Date of 1 Ozomatli, Seler (1902-1923:2:923) Called Atten- Nicholson and Quiñones Keber 1983:No

CHAPTER 9 The BilimekPulqueVessel:Starlore, Calendrics,andCosmologyof LatePostclassicCentralMexico The Bilimek Vessel of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna is a tour de force of Aztec lapidary art (Figure 1). Carved in dark-green phyllite, the vessel is covered with complex iconographic scenes. Eduard Seler (1902, 1902-1923:2:913-952) was the first to interpret its a function and iconographic significance, noting that the imagery concerns the beverage pulque, or octli, the fermented juice of the maguey. In his pioneering analysis, Seler discussed many of the more esoteric aspects of the cult of pulque in ancient highland Mexico. In this study, I address the significance of pulque in Aztec mythology, cosmology, and calendrics and note that the Bilimek Vessel is a powerful period-ending statement pertaining to star gods of the night sky, cosmic battle, and the completion of the Aztec 52-year cycle. The Iconography of the Bilimek Vessel The most prominent element on the Bilimek Vessel is the large head projecting from the side of the vase (Figure 2a). Noting the bone jaw and fringe of malinalli grass hair, Seler (1902-1923:2:916) suggested that the head represents the day sign Malinalli, which for the b Aztec frequently appears as a skeletal head with malinalli hair (Figure 2b). However, because the head is not accompanied by the numeral coefficient required for a completetonalpohualli Figure 2. Comparison of face date, Seler rejected the Malinalli identification. Based on the appearance of the date 8 Flint on front of Bilimek Vessel with Aztec Malinalli sign: (a) face on on the vessel rim, Seler suggested that the face is the day sign Ozomatli, with an inferred Bilimek Vessel, note malinalli tonalpohualli reference to the trecena 1 Ozomatli (1902-1923:2:922-923). -

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Title PRECISE CHARACTERIZATION OF GUATEMALAN OBSIDIAN SOURCES, AND SOURCING OBSIDIAN ARTIFACTS FROM QUIRIGUA Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/78q0n6dc Author Stross, Fred H. Publication Date 1981 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California LBL-12252 Preprin t G.~ Submitted to American Antiquity PRECISE CHARACTERIZATION OF GUATEMALAN OBSIDIAN SOURCES, AND SOURCING OBSIDIAN ARTIFACTS FROM. QUIRIGUA Fred H. Stross, Payson Sheets, Frank Asaro, and Helen V. Michel January 1981 TWO-WEEK lOAN COPY This is a library Circulating Copy which may be borrowed for two weeks. For a personal retention copy, call Tech. Info. Dioision, Ext. 6782 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract W-7405-ENG-48 DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain conect information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor the Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any wananty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or the Regents of the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof or the Regents of the University of California. -

An Osteological Analysis of Human Remains From

AN OSTEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF HUMAN REMAINS FROM CUSIRISNA CAVE, NICARAGUA by Kendra L. Philmon A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida December 2012 Copyright by Kendra L. Philmon 2012 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without my thesis advisor Dr. Clifford T. Brown. The idea underlying the project was originally suggested to him by Dr. James Brady, and without this suggestion, we would know nothing about the skeletal remains from Cusirisna Cave. Dr. Brown has provided endless support throughout this process by explaining Mesoamerican archaeology and history, making research and reference suggestions, providing direction, arranging weekly meetings to discuss ideas, offering continuous review and editing, and for instilling confidence in my ability to complete the research. I will be forever grateful to the Department of Anthropology for the opportunity to conduct bioarchaeological research. Thank you to my committee members Drs. Broadfield and Detwiler for their assistance in the research and for reviewing this thesis. Thanks also to Harvard Peabody Museum for their kindness in allowing examination of the Cusirisna Cave collection, for accommodating my research, and especially to Dr. Viva Fisher for approving the radiocarbon sampling and for shipping the specimen, as well as for her support in procuring copies of the documentation and other matters. I also thank Dr. Patricia Kervick who provided access to Earl Flint's reports, and correspondence, made copies of them, and granted us permission to use them. -

Type Localities of Birds Described from Guatemala

PROCEEDINGS OF THE WESTERN FOUNDATION OF VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY VOL. 3 • JULY 1987 • NO. 2 TYPE LOCALITIES OF BIRDS DESCRIBED FROM GUATEMALA BY ROBERT W. DICKERMAN The PROCEEDINGS OF THE WESTERN FOUNDATION OF VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY (ISSN 0511-7550) are published at irregular intervals by the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology, 1100 Glendon Avenue, Los Angeles, California 90024. VOL. 3 JULY 1987 NO. 2 TYPE LOCALITIES OF BIRDS DESCRIBED FROM GUATEMALA BY ROBERT W. DICKERMAN WESTERN FOUNDATION OF VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY 1100 GLENDON AVENUE • (213) 208-8003 • LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90024 BOARD OF TRUSTEES ED N. HARRISON PRESIDENT DR. L. RICHARD MEWALDT VICE PRESIDENT LLOYD F. KIFF VICE PRESIDENT JULIA L. KIFF SECRETARY-TREASURER DR. DEAN AMADON DR. DAVID PARMELEE DR. HERBERT FRIEDMANN DR. ROBERT W. RISEBROUGH A.S. GLIKBARG THOMAS W. SEFTON DR. JOSEPH J. HICKEY DR. F. GARY STILES DR. THOMAS R. HOWELL PROF. J.C. VON BLOEKER, JR DR. JOE T. MARSHALL JOHN G. WILLIAMS DR. ROBERT T. ORR COL. L. R. WOLFE DIRECTOR LLOYD F. KIFF ASSOCIATE CURATOR COLLECTION MANAGER RAYMOND J. QUIGLEY CLARK SUMIDA EDITOR JACK C. VON BLOEKER. JR. A NON-PROFIT CORPORATION DEDICATED TO RESEARCH, EDUCATION, AND PUBLICATION IN ORNITHOLOGY, OOLOGY, MAMMALOGY, AND HERPETOLOGY TYPE LOCALITIES OF BIRDS DESCRIBED FROM GUATEMALA Robert W. Dickerman1 This compilation of the birds described from Guatemala and their type localities was begun in 1968 by preparing file cards on citations in Ludlow Griscom’s major report, “The Distribution of Bird-life in Guatemala” (Griscom 1932, hereinafter cited as LG’32). Interest in the project was renewed a decade later in the course of preparing a manuscript on the avifauna of the Pacific lowlands of southern Guatemala (Dickerman 1987).