The Defeat of the Great Bird in Myth and Royal Pageantry: a Mesoamerican Myth in a Comparative Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds Mosley Dianna Wilson University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Wilson, Mosley Dianna, "Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 853. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/853 ANCIENT MAYA AFTERLIFE ICONOGRAPHY: TRAVELING BETWEEN WORLDS by DIANNA WILSON MOSLEY B.A. University of Central Florida, 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Liberal Studies in the College of Graduate Studies at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2006 i ABSTRACT The ancient Maya afterlife is a rich and voluminous topic. Unfortunately, much of the material currently utilized for interpretations about the ancient Maya comes from publications written after contact by the Spanish or from artifacts with no context, likely looted items. Both sources of information can be problematic and can skew interpretations. Cosmological tales documented after the Spanish invasion show evidence of the religious conversion that was underway. Noncontextual artifacts are often altered in order to make them more marketable. An example of an iconographic theme that is incorporated into the surviving media of the ancient Maya, but that is not mentioned in ethnographically-recorded myths or represented in the iconography from most noncontextual objects, are the “travelers”: a group of gods, humans, and animals who occupy a unique niche in the ancient Maya cosmology. -

Introducing Izapa

Ancient Mesoamerica, 29 (2018), 255–264 Copyright © Cambridge University Press, 2018 doi:10.1017/S0956536118000494 INTRODUCING IZAPA Robert M. Rosenswiga and Julia Guernseyb aDepartment of Anthropology, State University of New York at Albany, Albany, New York 12222 bDepartment of Art and Art History, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78705 Abstract This paper introduces the articles that comprise this Special Issue on Izapa. First, we review early reporting and assessments of Izapa’s monuments as well as archaeological investigations undertaken at the site during the twentieth century. Next, we describe more recent developments in interpretation and new archeological excavations and survey data collected during the past two decades. The papers in this Special Issue present new information that contribute to our evolving understanding of Izapa during the millennium that stretches from the Middle Formative period through the Middle Classic period (700 b.c.–a.d. 600). They serve as a status report on our understanding of the still largely enigmatic ancient kingdom, its regional structure, and connections to contemporaneous Isthmian sites. INTRODUCTION Blanca collapsed after a few centuries, and population declined in the immediate region. Its demise was a continuation of a millennium Izapa followed a trajectory of settled life that began at the beginning of political volatility characterized by a succession of polities coa- of the second millennium b.c. in the Soconusco region of Chiapas lescing and collapsing on the coastal plain (Love 2002b, 2007, and neighboring Guatemala (Figure 1). A series of Early Formative 2011). This rise-and-fall sequence provided the context in which (1900–1000 b.c., all dates calibrated) centers characterize the mounded architecture was adopted at Izapa sometime around 800 Mazatán zone of the Soconusco region (Clark and Pye 2000; b.c. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

The Carved Human Femprs from Tomb 1, Chiapa De Corzo, Chiapas, Mexico

PAPERS of the NEW WOR LD ARCHAEOLO G ICAL FOUNDATION NUMBER SIX THE CARVED HUMAN FEMPRS FROM TOMB 1, CHIAPA DE CORZO, CHIAPAS, MEXICO by PIERRE AGRINIER PUBLICATION No. 5 NEW WORLD ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION ORINDA, CALIFORNIA 1960 NEW WORLD ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION 1960 OFFICERS THOMAS STUART FERGUSON, President 1 Irving Lane, Orinda, California ALFRED V. KIDDER, PH.D., First Vice-President MILTON R. HUNTER, PH.D., Vice-President ScoTT H. DUNHAM, Secretary-Treasurer J. ALDEN MASON, PH.D., Editor and Field Advisor GARETH W. LowE, Field Director, 1956-1959 FREDRICK A. PETERSON, Field Director, 1959-1960 DIRECTORS ADVISORY COMMITTEE SCOTT H. DUNHAM, C.P.A. PEDRO ARMILLAS, PH.D. THOMAS STUART FERGUSON, ESQ. GORDON F. EKHOLM, PH.D. M. WELLS JAKEMAN, PH.D. J. POULSON HUNTER, M.D. ALFRED V. KIDDER, PH.D. MILTON R. HUNTER, PH.D. ALFRED V. KIDDER, PH.D. EDITORIAL OFFICE NICHOLAS G. MORGAN, SR. ALDEN MASON LE GRAND RICHARDS J. UNIVERSITY MUSEUM ERNEST A. STRONG UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Philadelphia 4, Pa. J. ALDEN MASON EDITOR Orders for and correspondence regarding the publications of The New World Archaeological Foundation should be sent to SCOTT H. DUNHAM, Secretary 510 Crocker Building San Francisco 4, California Price $2.00 Printed by THE LEGAL INTELLIGENCER Philadelphia 4, Pa. PAPERS of the NEW WOR LD ARCHAEOLO G ICAL FOUNDATION NUMBER SIX THE CARVED HUMAN FEMURS FROM TOMB 1, CHIAP A DE CORZO, CHIAPAS, MEXICO by PIERRE AGRINIER PUB LICATION No. 5 NEW WoRLD ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION ORINDA, CALIFORNIA 1960 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 I. DESCRIPTION ..•...........•......................•... 2 Bone 1 .................................... 2 Bone 2 2 Bone 3 2 Bone 4 3 Technique ................................................ -

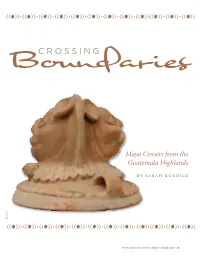

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

A New Artistic Rendering of Izapa Stela 5: a Step Toward Improved Interpretation

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 8 Number 1 Article 6 1-31-1999 A New Artistic Rendering of Izapa Stela 5: A Step toward Improved Interpretation John E. Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Clark, John E. (1999) "A New Artistic Rendering of Izapa Stela 5: A Step toward Improved Interpretation," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol8/iss1/6 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title A New Artistic Rendering of Izapa Stela 5: A Step toward Improved Interpretation Author(s) John E. Clark Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 8/1 (1999): 22–33, 77. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract Aided by creative techniques, Ajáx Moreno carefully prepared more accurate, detailed renderings of the Izapa monuments, including Stela 5, with its com- plex scenes of gods and other supernatural creatures, royalty, animals invested with mythic and value symbolism, and mortals. The author raises relevant questions about reconciling Jakeman’s view with the new drawing: Are there Old World connections? Can Izapa be viewed as a Book of Mormon city? Did the Nephites know of Lehi’s dream? Are there name glyphs on the stela? The scene, if it does not depict Lehi’s dream, fits clearly in Mesoamerican art in theme, style, technical execution, and meaning. -

Sumpit (Blowgun)

Journal of Education, Teaching and Learning Volume 3 Number 1 March 2018. Page 113-120 p-ISSN: 2477-5924 e-ISSN: 2477-4878 Journal of Education, Teaching, and Learning is licensed under A Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. Sumpit (Blowgun) as Traditional Weapons with Dayak High Protection (Study Documentation of Local Wisdom Weak Traditional Weapons of Kalimantan) Hamid Darmadi IKIP PGRI Pontianak, Pontianak, Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The Dayak ancestors who live amid lush forests with towering tree trees and inhabited by a variety of wild animals and wild animals, inspire for the Dayak's ancestors to make weapons that not only protect themselves from the ferocity of forest life but also have been able to sustain the existence of their survival. Such living conditions have motivated the Dayak ancestors to make weapons called "blowgun" Blowgun as weapons equipped with blowgun called damak. Damak made of bamboo, stick and the like are tapered and given sharp-sharp so that after the target is left in the victim's body. In its use damak smeared with poison. Poison blowgun smeared on the damak where the ingredients used are very dangerous, a little scratched it can cause death. Poison blowgun can be made from a combination of various sap of a particular tree and can also be made from animals. Along with the development of blowgun, era began to be abandoned by Dayak young people. To avoid the typical weapons of this high-end Dayak blowgun from extinction, need to be socialized especially to the young generation and to Dayak young generation especially in order, not to extinction. -

By ROBERT L. RANDS

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology BuUetin 157 Anthropological Papers, No. 48 Some ManifestatioDs of Water in Mesoamerican Art By ROBERT L. RANDS 265 1 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 27 The better established occurrences of water 273 Types of associations 273 The Maya codices 277 The Mexican codices 280 Aztec and Teotihuacdn murals, sculptures, and ceramics 285 Summary 291 The proposed identifications of water 292 Artistic approach to the identifications 292 Non-Maya murals, sculptures, and ceramics 293 Maya murals, sculptures, and ceramics 298 General considerations 298 Highest probability (A) 302 Probability B : paraphernalia and secondary associations 315 Probability B : fang, tongue, or water (?) 320 Artistic typology and miscellany 322 Water and the water lily 330 Conclusions 333 Appendix A. Nonartistic data and current reconstructions 342 Direct water associations : physiological data 342 Water from container 344 Water from mouth 348 Water from eye 348 Water from breast 350 Water from between legs 350 Water from body (pores ?) 350 Water from hand 352 Water from other object held in hand 354 Waterlike design from head 355 Glyph in water 365 Object in water 359 Tlaloc 359 Anthropomorphic Long-nosed God 359 Female water deity 369 Black god (M, B) 360 Miscellaneous anthropomorphic figures 360 Frog 360 Serpent 361 Jaguar (ocelot) 361 Bird 363 Miscellaneous animal 363 Serpentine-saurian monster 364 Detached rear head of monster 364 Other grotesque head, face 365 267 268 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY [Bull. 157 Appendix A. Nonartistic data and current reconstructions—Con. page Death, misfortune, destruction _. 365 Water descending on surface water 365 Water descending on figure 366 The bending-over rainmaker 366 The sky monster and its affiliates 366 Balanced water and vegetation 367 Summary 367 Appendix B. -

Manufactured Light Mirrors in the Mesoamerican Realm

Edited by Emiliano Gallaga M. and Marc G. Blainey MANUFACTURED MIRRORS IN THE LIGHT MESOAMERICAN REALM COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables xiii Chapter 1: Introduction Emiliano Gallaga M. 3 Chapter 2: How to Make a Pyrite Mirror: An Experimental Archaeology Project Emiliano Gallaga M. 25 Chapter 3: Manufacturing Techniques of Pyrite Inlays in Mesoamerica Emiliano Melgar, Emiliano Gallaga M., and Reyna Solis 51 Chapter 4: Domestic Production of Pyrite Mirrors at Cancuén,COPYRIGHTED Guatemala MATERIAL Brigitte KovacevichNOT FOR DISTRIBUTION73 Chapter 5: Identification and Use of Pyrite and Hematite at Teotihuacan Julie Gazzola, Sergio Gómez Chávez, and Thomas Calligaro 107 Chapter 6: On How Mirrors Would Have Been Employed in the Ancient Americas José J. Lunazzi 125 Chapter 7: Iron Pyrite Ornaments from Middle Formative Contexts in the Mascota Valley of Jalisco, Mexico: Description, Mesoamerican Relationships, and Probable Symbolic Significance Joseph B. Mountjoy 143 Chapter 8: Pre-Hispanic Iron-Ore Mirrors and Mosaics from Zacatecas Achim Lelgemann 161 Chapter 9: Techniques of Luminosity: Iron-Ore Mirrors and Entheogenic Shamanism among the Ancient Maya Marc G. Blainey 179 Chapter 10: Stones of Light: The Use of Crystals in Maya Divination John J. McGraw 207 Chapter 11: Reflecting on Exchange: Ancient Maya Mirrors beyond the Southeast Periphery Carrie L. Dennett and Marc G. Blainey 229 Chapter 12: Ritual Uses of Mirrors by the Wixaritari (Huichol Indians): Instruments of Reflexivity in Creative Processes COPYRIGHTEDOlivia Kindl MATERIAL 255 NOTChapter FOR 13: Through DISTRIBUTION a Glass, Brightly: Recent Investigations Concerning Mirrors and Scrying in Ancient and Contemporary Mesoamerica Karl Taube 285 List of Contributors 315 Index 317 vi contents 1 “Here is the Mirror of Galadriel,” she said. -

Chopsticks As a Typical Dayak Borneo Weapon

Chopsticks as a Typical Dayak Borneo Weapon Hamid Darmadi {[email protected]} IKIP PGRI Pontianak Abstract: The ancestors of the Dayak tribe who live amid dense forests and inhabited by various wild animals, inspire and motivate the Dayak tribe to make reliable weapons that are not only able to protect themselves from the fierce forest life, but also able to sustain the existence of the Dayak tribe as a whole . The ferocious wilderness of Borneo island has tapered the determination and enthusiasm "Dayak ancestors make" Typical "weapons called" chopsticks. "Chopsticks are made of iron wood (ironwood). Chopsticks have a length of 1.5 to 2cm. The best size for a chopstick Chopsticks consist of three main parts, namely: Chopsticks, chopsticks (damak) and chopsticks (spear made of selected iron tied to the end of the chopsticks). Chopsticks that rely on this blowing power, has a shooting accuracy of up to 200 meters, effective shooting distance of 25 to 30 meters to "typical" which makes the chopstick gun deadly because at the end of the dam is spiked / smeared poison in the form of gum ipuh and a mixture of deadly animals that are said to have no antidote. with the advent of Technology and Knowledge, chopsticks began to be rarely produced as weapons of war, but more at p production as a sports tool to clot and order. Keywords: Typical Dayak Weapon Chopsticks 1 Introduction 1.1 Background for making Chopsticks Weapons Living amidst a dense forest with tree trees that looms high and is inhabited by various wild and wild animals, has inspired Dayaks to make weapons that are not only able to protect them from the fierce forest life, but also able to sustain their lives both materially and moral. -

Creation Cosmos

Creation, Cosmos, and the Imagery of Palenque and Copan Linda Schele and Khristaan D. Villela University of Texas, Austin At the 1992 Texas Meetings, Schele published in Schele (1992) and Freidel, (1992) presented a new interpretation of the Schele, and Parker (1993), we discuss here creation myth and the imagery associated only the main features of the story and its with it, as they are recorded in Classic Period association to astronomical phenomena. inscriptions. There is continuing debate The story of creation on Quirigua about some of the details in this reconstruc- Stela C (fig. 1) gives us the most detailed tion, but various researchers (Schele, Grube, information about the first moment. The text Nahm, R. Johnson, and Quenon) have tested describes the first event as the “appearance some of its patterns and found them to be or manifestation of an image” (halhi productive. This new reconstruction resulted k’ohba). Here the image that appeared was from the decipherment of texts at Quirigua, of three stone-settings (u tz’apwa tun), Palenque, and elsewhere, relating the events described as a jaguar throne stone placed by of creation and associating them with the Paddler Gods at a place called Na-Ho- various constellations, the Milky Way, and Chan, ‘House (or First or Female) Five- their movement through the sky. Since a Sky’; a snake throne stone set up by an detailed discussion of the creation story is unknown god at Kab-Kah,1 ‘Earth-town’; Fig. 1. The Creation Passage from Quirigua Stela C. 1 a. A council of gods aiding in the setting of the jaguar throne. -

The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the Cult of Sacred War at Teotihuacan

The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the cult of sacred war at Teotihuacan KARLA. TAUBE The Temple of Quetzalcoatl at Teotihuacan has been warrior elements found in the Maya region also appear the source of startling archaeological discoveries since among the Classic Zapotee of Oaxaca. Finally, using the early portion of this century. Beginning in 1918, ethnohistoric data pertaining to the Aztec, Iwill discuss excavations by Manuel Gamio revealed an elaborate the possible ethos surrounding the Teotihuacan cult and beautifully preserved facade underlying later of war. construction. Although excavations were performed intermittently during the subsequent decades, some of The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the Tezcacoac the most important discoveries have occurred during the last several years. Recent investigations have Located in the rear center of the great Ciudadela revealed mass dedicatory burials in the foundations of compound, the Temple of Quetzalcoatl is one of the the Temple of Quetzalcoatl (Sugiyama 1989; Cabrera, largest pyramidal structures at Teotihuacan. In volume, Sugiyama, and Cowgill 1988); at the time of this it ranks only third after the Pyramid of the Moon and writing, more than eighty individuals have been the Pyramid of the Sun (Cowgill 1983: 322). As a result discovered interred in the foundations of the pyramid. of the Teotihuacan Mapping Project, it is now known Sugiyama (1989) persuasively argues that many of the that the Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the enclosing individuals appear to be either warriors or dressed in Ciudadela are located in the center of the ancient city the office of war. (Mill?n 1976: 236). The Ciudadela iswidely considered The archaeological investigations by Cabrera, to have been the seat of Teotihuacan rulership, and Sugiyama, and Cowgill are ongoing, and to comment held the palaces of the principal Teotihuacan lords extensively on the implications of their work would be (e.g., Armillas 1964: 307; Mill?n 1973: 55; Coe 1981: both premature and presumptuous.