Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

Agave Beverage

● ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES Agave salmiana Waiting for the sunrise ‘Tequila to wake the living; mezcal to wake the dead’ - old Mexican proverb. Before corn was ever domesticated, agaves (Agave spp.) identifi ed it with a similar plant found at home. Agaves fl ower only once (‘mono- were one of the main carbohydrate sources for humans carpic’), usually after they are between in what is today western and northern Mexico and south- 8-10 years old, and the plant will then die if allowed to set seed. This trait gives western US. Agaves (or magueyes) are perennial, short- rise to their alternative name of ‘century stemmed, monocotyledonous succulents, with a fl eshy leaf plants’. Archaeological evidence indicates base and stem. that agave stems and leaf bases (the ‘heads’, or ‘cores’) and fl owering stems By Ian Hornsey and ’ixcaloa’ (to cook). The name applies have been pit-cooked for eating in Mes- to at least 100 Mexican liquors that oamerica since at least 9,000 BC. When hey belong to the family Agavaceae, have been distilled with alembics or they arrived, the Spaniards noted that Twhich is endemic to America and Asian-type stills. Alcoholic drinks from native peoples produced ‘agave wine’ whose centre of diversity is Mexico. agaves can be divided into two groups, although their writings do not make it Nearly 200 spp. have been described, according to treatment of the plant: ’cut clear whether this referred to ‘ferment- 150 of them from Mexico, and around bud-tip drinks’ and ’baked plant core ed’ or ‘distilled’ beverages. This is partly 75 are used in that country for human drinks’. -

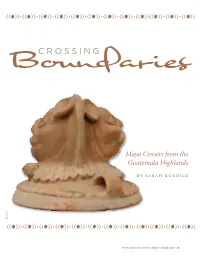

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

Adeuda El Ingenio $300 Millones a Cañeros

( Reducir la Deuda y Créditos Nuevos Requiere México (INFORMACION COLS . 1 Y 8) 'HOTELAMERICA' -1-' . ' &--&-- SUANFITRION.EN COLIMA MORELOS No . 162 /(a TELS. 2 .0366 Y 2 .95 .96 o~ima COLIMA, COL ., MEX . Fundador Director General Año Colima, Col ., Jueves 16 de Marzo de 1989 . Número XXXV Manuel Sánchez Silva Héctor Sánchez de la Madrid 11,467 Adeuda el Ingenio $300 Millones a Cañeros os Costos del Corte de Caña Provocan Cuevas Isáis : pérdidas por 200 Millones de Pesos Pésimas Ventas en Restaurantes • Situación insólita en la vida de la factoría : Romero Velasco . Cayeron en un 40% • Falso que se mejore punto de sacarosa con ese tipo de corte "Las ventas en la in- dustria restaurantera local I Se ha reducido en 20% el ritmo de molienda por el problema son pésimas, pues han Por Héctor Espinosa Flores decaído en un 40 por ciento, pero pensamos que en esta Independientemente de los problemas tema de corte de la caña se tendrá un me- temporada vacacional de que ha ocasionado la disposición de modi- jor aprovechamiento y por lo tanto un me- Semana Santa y Pascua nos ficar la técnica del corte de caña y que ha jor rendimiento de punto de sacarosa arri- nivelaremos con la llegada a provocado pérdidas a los productores por ba del 8.3 por ciento, pero hasta ahora no Colima de muchos turistas 200 millones de pesos, ahora el ingenio de se ha llegado ni al 8 por ciento, por lo que foráneos aunque no abusa- Quesería tiene un adeudo de 300 millones los productores están confirmando que remos, porque los precios de pesos de la primera preliquidación, al- ese sistema beneflcla, sino que perjudica . -

Guerrero En Movimiento

..._------------_..- TRACE Travaux et Recherches dans les Amériques du Centre TRACE est une revue consacrée aux travaux et recherches dans les Amé riques du Centre. Elle est publiée semestriellement par le Centre Français d'Études Mexicaines et Centraméricaines Sierra Leona 330 11000 México DF 'Zr 5405921/5405922 FAX 5405923 [email protected] Conseil de rédaction Claude Baudez, Georges Baudot, Michel Bertrand, Patricia Carot, Georges Couffignal, Olivier Dabène, Danièle Dehouve, Olivier Dollfus, Henri Favre, François-Xavier Guerra, Marc Humbert, Yvon Le Bot, Véronique Gervais, Dominique Michelet, Aurore Monod-Becquelin, Pierre Ragon et Alain Vanneph Comité de lecture Martine Dauzier, Danièle Dehouve, Roberto Diego Quintana, Esther Katz, Jean·Yves Marchal, Guilhem Olivier, Juan M. Pérez Zevallos et Charles-Édouard de Suremain Coordination de la revue Martine Dauzier Maquette de la couverture Stéphen Rostain Coordination du numéro Aline Hémond et Marguerite Bey Composition de la couverture Montage réalisé par Rodolfo Avila à partir des photos de lui-même, d'A. Hémond et Direction éditoriale de S. Villela. Joëlle Gaillac Édition du numéro Impression Concepci6n Asuar Impresi6n y DiselÏo Suiza 23 bis, colonia Portales Composition et mise en page México DF Concepci6n Asuar et Rodolfo Avila Révision des textes Le présent numéro de Trace a été coédité Concepci6n Asuar par l'a RS TOM et par le C E MCA Dessins et photos ISSN 0185-6286. Année 1998. Rodolfo Avila / 80mmaire / Indice PROLOGUE/PRÓLOGO Aline Hémond et Marguerite Bey 3 Guerrero: modelo para armar Armando Bartra 9 Espacios de poder y reproducción social en la Montaña de Guerrero Joaquín Flores y Beatriz Canabal 20 Simbolismo y ritual en la Montaña de Guerrero Samuel L. -

Manufactured Light Mirrors in the Mesoamerican Realm

Edited by Emiliano Gallaga M. and Marc G. Blainey MANUFACTURED MIRRORS IN THE LIGHT MESOAMERICAN REALM COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables xiii Chapter 1: Introduction Emiliano Gallaga M. 3 Chapter 2: How to Make a Pyrite Mirror: An Experimental Archaeology Project Emiliano Gallaga M. 25 Chapter 3: Manufacturing Techniques of Pyrite Inlays in Mesoamerica Emiliano Melgar, Emiliano Gallaga M., and Reyna Solis 51 Chapter 4: Domestic Production of Pyrite Mirrors at Cancuén,COPYRIGHTED Guatemala MATERIAL Brigitte KovacevichNOT FOR DISTRIBUTION73 Chapter 5: Identification and Use of Pyrite and Hematite at Teotihuacan Julie Gazzola, Sergio Gómez Chávez, and Thomas Calligaro 107 Chapter 6: On How Mirrors Would Have Been Employed in the Ancient Americas José J. Lunazzi 125 Chapter 7: Iron Pyrite Ornaments from Middle Formative Contexts in the Mascota Valley of Jalisco, Mexico: Description, Mesoamerican Relationships, and Probable Symbolic Significance Joseph B. Mountjoy 143 Chapter 8: Pre-Hispanic Iron-Ore Mirrors and Mosaics from Zacatecas Achim Lelgemann 161 Chapter 9: Techniques of Luminosity: Iron-Ore Mirrors and Entheogenic Shamanism among the Ancient Maya Marc G. Blainey 179 Chapter 10: Stones of Light: The Use of Crystals in Maya Divination John J. McGraw 207 Chapter 11: Reflecting on Exchange: Ancient Maya Mirrors beyond the Southeast Periphery Carrie L. Dennett and Marc G. Blainey 229 Chapter 12: Ritual Uses of Mirrors by the Wixaritari (Huichol Indians): Instruments of Reflexivity in Creative Processes COPYRIGHTEDOlivia Kindl MATERIAL 255 NOTChapter FOR 13: Through DISTRIBUTION a Glass, Brightly: Recent Investigations Concerning Mirrors and Scrying in Ancient and Contemporary Mesoamerica Karl Taube 285 List of Contributors 315 Index 317 vi contents 1 “Here is the Mirror of Galadriel,” she said. -

Estado De Yucatán

119 CUADRO 9." POBLACION TOTAL SEGUN SU RELIGION, POR SEXO POBLACION PROTESTANTE MUNICIPIO Y SEXO TOTAL CATOLICA 0 ISRAELITA OTRA NINGUNA EVANGELICA MAMA 1 482 1 470 11 1 húKBKES 757 752 4 1 MLJcRES 725 718 7 HANI 2 598 2 401 189 3 5 HCMBRtS 1 2 3ü 1 129 96 1 4 MLJtKcS 1 368 1 2 72 93 2 1 MAXCANL 1C SoC 1C 206 64 3 10 27 7 kCMbRES 5 179 4 988 38 1 5 147 ML JERE 3 i 3ól í 218 26 2 5 130 tlAYAPAN 1 CC4 94C 3 61 HOMJjíl-S 5C2 465 2 35 MUJtRtS 5C2 475 1 26 MtRIDA 241 Sí4 234 213 4 188 76 838 2 649 HÜMBRtS 117 12a 112 996 1 963 35 448 1 684 MUJERES 124 6je 121 215 2 225 41 390 965 PÚCUChA 1 523 1 ¡369 33 21 HJMdRES 1 C21 966 17 16 MLJERtS 902 883 16 3 MGTUL 2C 994 19 788 602 12 24 568 l-OHSKÍS U CLC 5 344 297 9 17 333 MUJERES 1C S94 1C 44* 3C5 7 235 MUÑA 6 k.12 5 709 179 1 123 hJP3KES 2 5u5 2 763 77 65 MUJERES i 1C7 2 946 1C2 1 58 MUXUPIP 1 EJ7 1 8C9 2 26 Hü MdR E S 935 914 1 20 MUJ E Rt S sc¿ 895 ] 6 GPICHEN ¿ Eia 2 538 19 1 HOMtíKtS 949 54 L 9 MUJERES 1 60 9 1 598 10 1 ÍXXUT2CAE 1C 35b 9 529 488 20 318 HOMBRES 4 7 i 1 4 296 251 11 173 MUJERES 5 624 5 233 237 9 145 PANABA 4 216 3 964 192 6 53 HOMüRcS 1 832 1 7C5 92 5 30 MUJERES 2 384 2 259 1C1 1 23 PE Tu 12 lis 11 ¢57 J52 1 12 163 HOMdREi 6 6 016 195 1 6 88 MUJERES 5 i¡79 i 641 157 6 75 PROGRESO 21 352 2C 131 74C 1 61 419 HLMdKE S 1C 1U2 9 482 348 1 30 241 MUJEKES 11 2 50 1C 649 392 31 178 CUINTANA RUO €69 5C2 366 HÚM3RES 477 2 74 20 3 MUJERES 392 229 163 RIC LAGARTOS 1 705 1 669 11 24 HLMdRES 692 87C 1C 12 MUJERES 813 759 1 12 SACALUM 2 457 2 355 54 48 HUMBAtá 1 201 1 244 32 25 1971 MUJERti 1 156 1 111 22 23 SAMAhlL 2 460 2 410 44 2 4 hCHBftES 1 362 1 335 24 1 2 Yucatán. -

Guadalajara Metropolitana Oportunidades Y Propuestas Prosperidad Urbana: D Oportunidades Y Propuestas

G PROSPERIDAD METROPOLITANA URBANA: GUADALAJARA METROPOLITANA OPORTUNIDADES Y PROPUESTAS PROSPERIDAD URBANA: D OPORTUNIDADES Y PROPUESTAS L PROSPERIDAD URBANA: OPORTUNIDADES Y PROPUESTAS GUADALAJARA METROPOLITANA GUADALAJARA Guadalajara Metropolitana Prosperidad urbana: oportunidades y propuestas Introducción 3 Guadalajara Metropolitana Proyecto: Prosperidad urbana: oportunidades y propuestas Acuerdo de Contribución entre el Programa de las Naciones Unidas para los Asentamientos Humanos (ONU-Habitat) y Derechos reservados 2017 el Gobierno del Estado de Jalisco. © Programa de las Naciones Unidas para los Consultores: Asentamientos Humanos, ONU-Habitat Sergio García de Alba, Luis F. Siqueiros, Víctor Ortiz, Av. Paseo de la Reforma 99, PB. Agustín Escobar, Eduardo Santana, Oliver Meza, Adriana Col. Tabacalera, CP. 06030, Ciudad de México. Olivares, Guillermo Woo, Luis Valdivia, Héctor Castañón, Tel. +52 (55) 6820-9700 ext. 40062 Daniel González. HS Number: HS/004/17S Colaboradores: ISBN Number: (Volume) 978-92-1-132726-7 Laura Pedraza, Diego Escobar, Néstor Platero, Rodrigo Flores, Gerardo Bernache, Mauricio Alcocer, Mario García, Se prohíbe la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra, Sergio Graf, Gabriel Corona, Verónica Díaz, Marco Medina, sea cual fuere el medio, sin el consentimiento por escrito Jesús Rodríguez, Carlos Marmolejo. del titular de los derechos. Exención de responsabilidad: Joan Clos Las designaciones empleadas y la presentación del Director Ejecutivo de ONU-Habitat material en el presente informe no implican la expresión de ninguna manera de la Secretaría de las Naciones Elkin Velásquez Unidas con referencia al estatus legal de cualquier país, Director Regional de ONU-Habitat para América Latina y territorio, ciudad o área, o de sus autoridades, o relativas el Caribe a la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites, o en lo que hace a sus sistemas económicos o grado de desarrollo. -

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2005 Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Benson, Jeffrey, "Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins" (2005). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 126. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/126 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. -

Formative Mexican Chiefdoms and the Myth of the "Mother Culture"

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 19, 1–37 (2000) doi:10.1006/jaar.1999.0359, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Formative Mexican Chiefdoms and the Myth of the “Mother Culture” Kent V. Flannery and Joyce Marcus Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1079 Most scholars agree that the urban states of Classic Mexico developed from Formative chiefdoms which preceded them. They disagree over whether that development (1) took place over the whole area from the Basin of Mexico to Chiapas, or (2) emanated entirely from one unique culture on the Gulf Coast. Recently Diehl and Coe (1996) put forth 11 assertions in defense of the second scenario, which assumes an Olmec “Mother Culture.” This paper disputes those assertions. It suggests that a model for rapid evolution, originally presented by biologist Sewall Wright, provides a better explanation for the explosive development of For- mative Mexican society. © 2000 Academic Press INTRODUCTION to be civilized. Five decades of subsequent excavation have shown the situation to be On occasion, archaeologists revive ideas more complex than that, but old ideas die so anachronistic as to have been declared hard. dead. The most recent attempt came when In “Olmec Archaeology” (hereafter ab- Richard Diehl and Michael Coe (1996) breviated OA), Diehl and Coe (1996:11) parted the icy lips of the Olmec “Mother propose that there are two contrasting Culture” and gave it mouth-to-mouth re- “schools of thought” on the relationship 1 suscitation. between the Olmec and the rest of Me- The notion that the Olmec of the Gulf soamerica. -

00-ARQUEOLOGIA 43-INDICE.Pmd

85 LAS CERÁMICAS TEMPRANAS EN EL ÁREA DEL DELTA DEL BALSAS Ma. de Lourdes López Camacho* Salvador Pulido Méndez** Las cerámicas tempranas en el área del delta del Balsas Los trabajos de investigación que hemos llevado a cabo en la desembocadura del río Balsas han dado algunas gratas sorpresas, entre ellas las relacionadas con los materiales cerámicos que atestiguan y son producto de un desarrollo social profundamente enraizado en el devenir de la región. En este escrito deseamos propiciar la reflexión sobre las cerámicas tempranas ubicadas en dicha área y sus relaciones con otras zonas culturales cercanas y lejanas. En este sentido retomamos algunos de los argumentos que desde mediados del siglo pasado se esbo- zaron sobre la conformación de un área cultural primigenia que abarcó regiones más allá de los límites de nuestro país y de lo que se conoce como Mesoamérica. Por otra parte, publicamos los materiales propios de la zona de nuestra investigación, a fin de que contribuyan a la difícil tarea de lograr una visión plausible sobre el desarrollo de los primeros grupos humanos de la América media. Archaeological work conducted at the mouth of the Balsas River have produced pleasant surprises, some of them related to ceramics that attest to and are the product of social process deeply rooted in the region’s development. In this paper we wish to promote reflection on early ceramics located in this zone and their relations with other nearby and distant cultural areas. In this line of thinking, we revive some of the ideas put forth since the mid-twentieth century that outlined the formation of an original cultural area that encompassed zones beyond the current borders of Mexico and what is known as Mesoamerica. -

Cultural Traditions of Ancient Mesoamerica Michael Shaw

FINDLAY Cultural Traditions of Cultural Traditions of Ancient Mesoamerica Ancient Mesoamerica Cultural Traditions of Ancient Mesoamerica describes ancient cultural traditions of the ofCultural Traditions Ancient Mesoamerica Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, and Aztecs, among others, providing students with a survey of EDITION Precontact Mesoamerica. The text features a multidisciplinary approach, including perspectives from archaeology, cultural history, epigraphy, art history, and ethnography. The book is organized into ten chapters and proceeds in roughly chronological order to reflect developmental changes in Mesoamerican culture from around 16kya to A.D. 1492. The opening chapter summarizes the foundational concerns of Mesoamerican studies. Chapters Two and Three explore the cultural development of Mesoamerica from the first migrations into the Americas to the Preclassic period. Chapter Four discusses various theories pertaining to culture change. In Chapters Five and Six, students examine Mesoamerica’s Classic period. Chapter Seven outlines the nature and importance of ancient and post-contact books and pictorial documents to the study of Mesoamerica. In Chapters Eight and Nine, students learn about the Classic Collapse, the Terminal Classic period, and the Post-Classic period. The final chapter describes the Spanish impact on Native Mesoamerican culture. Cultural Traditions of Ancient Mesoamerica is well suited for courses in anthropology, archaeology, ancient civilizations, ancient Mesoamerica, Latin American history, and Latin American studies. Michael Shaw Findlay earned his Ph.D. in curriculum/instruction in the Anthropology of Education Program at the University of Oregon. He has over 30 years of experience teaching at the secondary and post-secondary levels, including his work at California State University, Chico, and Butte College.