University of Florida Thesis Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

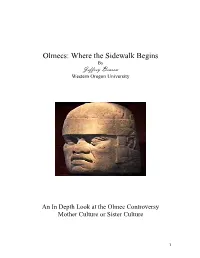

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2005 Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Benson, Jeffrey, "Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins" (2005). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 126. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/126 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. -

Formative Mexican Chiefdoms and the Myth of the "Mother Culture"

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 19, 1–37 (2000) doi:10.1006/jaar.1999.0359, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Formative Mexican Chiefdoms and the Myth of the “Mother Culture” Kent V. Flannery and Joyce Marcus Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1079 Most scholars agree that the urban states of Classic Mexico developed from Formative chiefdoms which preceded them. They disagree over whether that development (1) took place over the whole area from the Basin of Mexico to Chiapas, or (2) emanated entirely from one unique culture on the Gulf Coast. Recently Diehl and Coe (1996) put forth 11 assertions in defense of the second scenario, which assumes an Olmec “Mother Culture.” This paper disputes those assertions. It suggests that a model for rapid evolution, originally presented by biologist Sewall Wright, provides a better explanation for the explosive development of For- mative Mexican society. © 2000 Academic Press INTRODUCTION to be civilized. Five decades of subsequent excavation have shown the situation to be On occasion, archaeologists revive ideas more complex than that, but old ideas die so anachronistic as to have been declared hard. dead. The most recent attempt came when In “Olmec Archaeology” (hereafter ab- Richard Diehl and Michael Coe (1996) breviated OA), Diehl and Coe (1996:11) parted the icy lips of the Olmec “Mother propose that there are two contrasting Culture” and gave it mouth-to-mouth re- “schools of thought” on the relationship 1 suscitation. between the Olmec and the rest of Me- The notion that the Olmec of the Gulf soamerica. -

Diachronic and Synchronic Analyses of Obsidian Procurement in the Mixteca Alta, Oaxaca

FAMSI © 2004: Jeffrey P. Blomster Diachronic and Synchronic Analyses of Obsidian Procurement in the Mixteca Alta, Oaxaca Research Year: 2003 Culture: Mixtec Chronology: Pre-Classic Location: Nochixtlán Valley, Oaxaca, México Site: Etlatongo Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Introduction Background: The Mixteca Alta and Etlatongo Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis of Obsidian Intra- and Interregional Interaction: Diachronic and Synchronic Data Conclusion Acknowledgements List of Figures and Tables Sources Cited Appendix 1. Element Concentrations, Site Names and Source Names for Obsidian Artifacts from Oaxaca Abstract In order to determine the nature and extent of interregional interaction during the Early Formative period at Etlatongo, in the Nochixtlán Valley of Oaxaca, México, 207 obsidian samples have been sourced to determine the origin of each fragment. The results document that the ancient villagers utilized obsidian from nine sources, with the majority (65%) coming from the Parédon source, in Puebla. Differences in types of obsidian and frequencies between different contexts at Etlatongo show selective participation in various networks by the Early Formative villagers. These data contrast with those from Early Formative sites in the Nochixtlán Valley and the Cuicatlán Cañada, where the majority of obsidian comes from Guadalupe Victoria, Puebla. In order to understand changes through time, 106 Late Formative obsidian fragments from Etlatongo were sourced. Seven sources were utilized. While the Paredón source still maintained great importance, other sources comprised a larger portion of the sample than earlier, while several new sources were exploited. Samples from the Valley of Oaxaca and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec provide comparative data on Late Formative obsidian utilization. These data are crucial for understanding interaction and social complexity in the Mixteca Alta and beyond. -

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins by Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. The data collected links the Olmecs to other cultures in several areas such as writing, pottery and art. With this new found data two main theories have evolved. The first is that the Olmecs were the mother culture. This theory states that writing, the calendar and types of art originated under Olmec rule and later were spread to future generational tribes of Mesoamerica. The second main theory proposes that the Olmecs were one of many contemporary cultures all which acted sister cultures. The thought is that it was not the Olmecs who were the first to introduce writing or the calendar to Mesoamerica but that various indigenous surrounding tribes influenced and helped establish forms of writing, a calendar system and common types of art. -

Olmec Bloodletting: an Iconographic Study

Olmec Bloodletting: An Iconographic Study ROSEMARY A. JOYCE Peabody Museum, Harvard University RICHARD EDGING and KARL LORENZ University of Illinois, Urbana SUSAN D. GILLESPIE Illinois State University One of the most important of all Maya rituals was ceremonial bloodletting, either by drawing a cord through a hole in the tongue or by passing a stingray spine, pointed bone, or maguey thorn through the penis. Stingray spines used in the rite have often been found in Maya caches; in fact, so significant was this act among the Classic Maya that the perforator itself was worshipped as a god. This ritual must also have been frequently practiced among the earlier Olmec... Michael D. Coe in The Origins of Maya Civilization The iconography of bloodletting in the Early iconographic elements indicating autosacrifice, and Middle Formative (ca. 1200-500 B.C.) Olmec and glyphs referring to bloodletting. Most scenes symbol system is the focus of the present study.1 shown take place after the act of bloodletting and We have identified a series of symbols in large- include holding paraphernalia of autosacrifice, and small-scale stone objects and ceramics repre- visions of blood serpents enclosing ancestors, and senting perforators and a zoomorphic supernatural scattering blood in a ritual gesture. The parapher- associated with bloodletting. While aspects of nalia of bloodletting may also be held, not simply this iconography are comparable to later Classic as indications that an act of autosacrifice has Lowland Maya iconography of bloodletting, its taken place, but as royal regalia. Two elements deployment in public and private contexts dif- are common both in scenes of bloodletting and as fers, suggesting fundamental variation in the way royal regalia: the personified bloodletter, which bloodletting was related to political legitimation Coe (1977a:188) referred to as a god, and bands in the Formative Olmec and Classic Maya cases. -

Interpreting Olmec Style Symbolism at the Formative

THE DAWNING OF CREATION IN THE CENTRAL MEXICAN HIGHLANDS: INTERPRETING OLMEC STYLE SYMBOLISM AT THE FORMATIVE PERIOD SITES OF CHALCATZINGO, OXTOTITLÁN, AND JUXTLAHUACA by Brendan C. Stanley, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Anthropology August 2020 Committee Members F. Kent Reilly III, Chair David A. Freidel Jim F. Garber COPYRIGHT by Brendan C. Stanley 2020 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-533, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Brendan C. Stanley, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for education or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDEGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude towards my committee members, David A. Freidel and Jim F. Garber, for their guidance and support throughout the writing process. I would especially like to thank my committee chair, long time mentor, and friend, F. Kent Reilly III, for all the support and assistance throughout the past years. This thesis would not have been possible without all your help. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. -

Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks

Pre-Columbian Art at Dumbarton Oaks, No. 2 OLMEC ART AT DUMBARTON OAKS OLMEC ART AT DUMBARTON OAKS Karl A. Taube Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. Copyright © 2004 by Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C. Library of Congress Cataloging-in Publication Data to come To the memory of Carol Callaway, Alba Guadalupe Mastache, Linda Schele, and my sister, Marianna Taube—four who fought the good fight CONTENTS PREFACE Jeffrey Quilter ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi List of Plates xii List of Figures xiii Chronological Chart of Mesoamerica xv Maps xvi INTRODUCTION: THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF OLMEC RESEARCH 1 THE DUMBARTON OAKS COLLECTION 49 BIBLIOGRAPHY 185 APPENDIX 203 INDEX 221 Preface lmec art held a special place in the heart of Robert Woods Bliss, who built the collection now housed at Dumbarton Oaks and who, with his wife, Mildred, conveyed the gar- Odens, grounds, buildings, library, and collections to Harvard University. The first object he purchased, in 1912, was an Olmec statuette (Pl. 8); he commonly carried a carved jade in his pocket; and, during his final illness, it was an Olmec mask (Pl. 30) that he asked to be hung on the wall of his sick room. It is easy to understand Bliss’s predilection for Olmec art. With his strong preference for metals and polished stone, the Olmec jades were particularly appealing to him. Although the finest Olmec ceramics are masterpieces in their own right, he preferred to concen- trate his collecting on jades. As Karl Taube discusses in detail in this volume of Pre-Columbian Art at Dumbarton Oaks, Olmec jades are the most beautiful stones worked in Mesoamerica. -

Open NEJ Dissertation.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School OBSIDIAN EXCHANGE AND PIONEER FARMING IN THE FORMATIVE PERIOD TEOTIHUACAN VALLEY A Dissertation in Anthropology by Nadia E. Johnson ©2020 Nadia E. Johnson Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2020 The dissertation of Nadia E. Johnson was reviewed and approved by the following: Kenneth G. Hirth Professor of Anthropology Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee José Capriles Assistant Professor of Anthropology Kirk French Associate Teaching Professor of Anthropology Larry Gorenflo Professor of Landscape Architecture, Eleanor P. Stuckeman Chair in Design Timothy Ryan Program Head and Professor of Anthropology ii ABSTRACT: The Formative Period marked a period of rapid social change and population growth in the Central Highlands of Mexico, culminating in the emergence of the Teotihuacan state in the Terminal Formative. This dissertation explores several aspects of economic life among the people who occupied the Teotihuacan Valley prior to the development of the state, focusing on the Early and Middle Formative Periods (ca. 1500 – 500 B.C.) as seen from Altica (1200 – 850 B.C.), the earliest known site in the Teotihuacan Valley. Early Formative populations in the Teotihuacan Valley, and northern Basin of Mexico more broadly, were sparse during this period, likely because it is cool, arid climate was less agriculturally hospitable than the southern basin. Altica was located in an especially agriculturally marginal section of the Teotihuacan Valley’s piedmont. While this location is suboptimal for subsistence agriculturalists, Altica’s proximity to the economically important Otumba obsidian source suggests that other economic factors influenced settlement choice. -

Une 30, 2018: National Endowment for the Humanities Collaborati E Research Grant

)ORULGD6WDWH8QLYHUVLW\/LEUDULHV 2018 Final Performance Report, November 1, 2012 June 30, 2018: National Endowment for the Humanities Collaborative Research Grant Christopher L. von Nagy and Mary D. Pohl Title of Project: Origins of the Mesoamerican City: Ritual and Polity Name of Project Directors: Mary D. Pohl (FSU), with project co-directors Christopher L. von Nagy (UNR and FSU) and Paul Schmidt Schoenberg (UNAM). Follow this and additional works at DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] Cover Page Type of Report: National Endowment for the Humanities Collaborative Research Grant Final Performance Report, November 1, 2012 – June 30, 2018 Grant Number: RZ-51497-12 Title of Project: Origins of the Mesoamerican City: Ritual and Polity Name of Project Directors: Mary D. Pohl (FSU), with project co-directors Christopher L. von Nagy (UNR and FSU) and Paul Schmidt Schoenberg (UNAM). Name of Grantee Institution: Florida State University Date: September 30, 2018 Report authored by Christopher L. von Nagy and Mary D. Pohl Pohl, von Nagy, Schmidt Schoenberg Accomplishments Major goals The National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) awarded Florida State University (FSU) a collaborative research grant for the period November 1, 2012 through June 30, 2018. The Origins of the Mesoamerican City: Ritual and Polity at La Venta, Tabasco, Mexico grant co-directed by Mary D. Pohl (FSU), Christopher L. von Nagy (FSU/UNR), and Paul Schmidt Schoenberg (UNAM) has several primary goals: 1) to promote close -

An Analysis of Olmec Iconography

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2014 NATURALISM AND SUPERNATURALISM IN ANCIENT MESOAMERICA: AN ANALYSIS OF OLMEC ICONOGRAPHY Sarah Silberberg Melville The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Melville, Sarah Silberberg, "NATURALISM AND SUPERNATURALISM IN ANCIENT MESOAMERICA: AN ANALYSIS OF OLMEC ICONOGRAPHY" (2014). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4198. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4198 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATURALISM AND SUPERNATURALISM IN ANCIENT MESOAMERICA: AN ANALYSIS OF OLMEC ICONOGRAPHY By SARAH SILBERBERG MELVILLE Bachelor of Fine Arts, California State University East Bay, Hayward, California, 2006 Bachelor of Science, California Maritime Academy, Vallejo, California 1983 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art in Art with a concentration in Art History The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2014 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Julia Galloway, Director School of Art H. Rafael Chacón, Professor School of Art Valerie Hedquist, Professor School of Art Mary Ann Bonjorni, Professor School of Art Kelly J. Dixon, Professor Anthropology Department © COPYRIGHT by Sarah Silberberg Melville 2014 All Rights Reserved. Melville, Sarah, M.A., Spring 2014 Art History Naturalism and Supernaturalism in Ancient Mesoamerica: An Analysis of Olmec Iconography H. -

Integrating Archaeology and History in Oaxaca, Mexico

Contents Acknowledgments ix 1. From “1-Eye” to Bruce Byland: Literate Societies and Integrative Approaches in Oaxaca Danny Zborover 1 2. The Convergence of History and Archaeology in Mesoamerica Ronald Spores 55 3. Bruce Edward Byland, PhD: 1950–2008 John M.D. Pohl 75 4. Multidisciplinary Fieldwork in Oaxaca Viola König 83 5. Mythstory and Archaeology: Of Earth Goddesses, Weaving Tools, and Buccal Masks Geoffrey G. McCafferty and Sharisse D. McCafferty 97 6. Reconciling Disparate Evidence between the Mixtec Historical Codices and Archaeology: The Case of “Red and White Bundle” and “Hill of the Wasp” Bruce E. Byland 113 vii viii Contents 7. Mixteca-Puebla Polychromes and the Codices Michael D. Lind 131 8. Pluri-Ethnic Coixtlahuaca’s Longue Durée Carlos Rincón Mautner 157 9. The Archaeology and History of Colonialism, Culture Contact, and Indigenous Cultural Development at Teozacoalco, Mixteca Alta Stephen L. Whittington and Andrew Workinger 209 10. Salt Production and Trade in the Mixteca Baja: The Case of the Tonalá- Atoyac-Ihualtepec Salt Works Bas van Doesburg and Ronald Spores 231 11. Integrating Oral Traditions and Archaeological Practice: The Case of San Miguel el Grande Liana I. Jiménez Osorio and Emmanuel Posselt Santoyo 263 12. Decolonizing Historical Archaeology in Southern Oaxaca, and Beyond Danny Zborover 279 13. Prehispanic and Colonial Chontal Communities on the Eastern Oaxaca Coast on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest Peter C. Kroefges 333 14. Locating the Hidden Transcripts of Colonialism: Archaeological and Historical Evidence from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Judith Francis Zeitlin 363 15. Using Nineteenth-Century Data in Contemporary Archaeological Studies: The View from Oaxaca and Germany Viola König and Adam T. -

Early Evidence of the Ballgame in Oaxaca, Mexico

Early evidence of the ballgame in Oaxaca, Mexico Jeffrey P. Blomster1 Department of Anthropology, George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052 Edited* by Michael D. Coe, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and approved April 6, 2012 (received for review February 27, 2012) As a defining characteristic of Mesoamerican civilization, the ball- both the Maya Maize God and its royal impersonators dressed game has a long and poorly understood history. Because the ball- as ballplayers. game is associated with the rise of complex societies, understand- The ballgame did not operate in a vacuum but was tied with ing its origins also illuminates the evolution of socio-politically other social and political practices. The ballgame expressed cos- complex societies. Although initial evidence, in the form of ceramic mological concepts about how the world operated, and political figurines, dates to 1700 BCE, and the oldest known ballcourt dates leaders, responsible for providing life and fertility, were closely to 1600 BCE, the ritual paraphernalia and ideology associated with linked with this social practice. Not coincidentally, the ballgame the game appear around 1400 BCE, the start of the so-called Early appeared around the same time as rank or chieflysocietyandhas Horizon, defined by the spread of Olmec-style symbols across Mes- been implicated as central to the processes of social differentiation oamerica. Early Horizon evidence of ballgame paraphernalia both (4, 5). The earliest depiction in monumental art of public leaders, identical to and different from that of the Gulf Coast Olmec can be the Early Horizon colossal heads of the Olmec, has been inter- seen on figurines from coastal Chiapas and the central highlands preted as sporting headgear related to the ballgame (6).