UC Riverside Previously Published Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

Manufactured Light Mirrors in the Mesoamerican Realm

Edited by Emiliano Gallaga M. and Marc G. Blainey MANUFACTURED MIRRORS IN THE LIGHT MESOAMERICAN REALM COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables xiii Chapter 1: Introduction Emiliano Gallaga M. 3 Chapter 2: How to Make a Pyrite Mirror: An Experimental Archaeology Project Emiliano Gallaga M. 25 Chapter 3: Manufacturing Techniques of Pyrite Inlays in Mesoamerica Emiliano Melgar, Emiliano Gallaga M., and Reyna Solis 51 Chapter 4: Domestic Production of Pyrite Mirrors at Cancuén,COPYRIGHTED Guatemala MATERIAL Brigitte KovacevichNOT FOR DISTRIBUTION73 Chapter 5: Identification and Use of Pyrite and Hematite at Teotihuacan Julie Gazzola, Sergio Gómez Chávez, and Thomas Calligaro 107 Chapter 6: On How Mirrors Would Have Been Employed in the Ancient Americas José J. Lunazzi 125 Chapter 7: Iron Pyrite Ornaments from Middle Formative Contexts in the Mascota Valley of Jalisco, Mexico: Description, Mesoamerican Relationships, and Probable Symbolic Significance Joseph B. Mountjoy 143 Chapter 8: Pre-Hispanic Iron-Ore Mirrors and Mosaics from Zacatecas Achim Lelgemann 161 Chapter 9: Techniques of Luminosity: Iron-Ore Mirrors and Entheogenic Shamanism among the Ancient Maya Marc G. Blainey 179 Chapter 10: Stones of Light: The Use of Crystals in Maya Divination John J. McGraw 207 Chapter 11: Reflecting on Exchange: Ancient Maya Mirrors beyond the Southeast Periphery Carrie L. Dennett and Marc G. Blainey 229 Chapter 12: Ritual Uses of Mirrors by the Wixaritari (Huichol Indians): Instruments of Reflexivity in Creative Processes COPYRIGHTEDOlivia Kindl MATERIAL 255 NOTChapter FOR 13: Through DISTRIBUTION a Glass, Brightly: Recent Investigations Concerning Mirrors and Scrying in Ancient and Contemporary Mesoamerica Karl Taube 285 List of Contributors 315 Index 317 vi contents 1 “Here is the Mirror of Galadriel,” she said. -

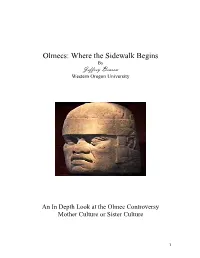

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2005 Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Benson, Jeffrey, "Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins" (2005). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 126. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/126 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. -

Formative Mexican Chiefdoms and the Myth of the "Mother Culture"

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 19, 1–37 (2000) doi:10.1006/jaar.1999.0359, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Formative Mexican Chiefdoms and the Myth of the “Mother Culture” Kent V. Flannery and Joyce Marcus Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1079 Most scholars agree that the urban states of Classic Mexico developed from Formative chiefdoms which preceded them. They disagree over whether that development (1) took place over the whole area from the Basin of Mexico to Chiapas, or (2) emanated entirely from one unique culture on the Gulf Coast. Recently Diehl and Coe (1996) put forth 11 assertions in defense of the second scenario, which assumes an Olmec “Mother Culture.” This paper disputes those assertions. It suggests that a model for rapid evolution, originally presented by biologist Sewall Wright, provides a better explanation for the explosive development of For- mative Mexican society. © 2000 Academic Press INTRODUCTION to be civilized. Five decades of subsequent excavation have shown the situation to be On occasion, archaeologists revive ideas more complex than that, but old ideas die so anachronistic as to have been declared hard. dead. The most recent attempt came when In “Olmec Archaeology” (hereafter ab- Richard Diehl and Michael Coe (1996) breviated OA), Diehl and Coe (1996:11) parted the icy lips of the Olmec “Mother propose that there are two contrasting Culture” and gave it mouth-to-mouth re- “schools of thought” on the relationship 1 suscitation. between the Olmec and the rest of Me- The notion that the Olmec of the Gulf soamerica. -

The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the Cult of Sacred War at Teotihuacan

The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the cult of sacred war at Teotihuacan KARLA. TAUBE The Temple of Quetzalcoatl at Teotihuacan has been warrior elements found in the Maya region also appear the source of startling archaeological discoveries since among the Classic Zapotee of Oaxaca. Finally, using the early portion of this century. Beginning in 1918, ethnohistoric data pertaining to the Aztec, Iwill discuss excavations by Manuel Gamio revealed an elaborate the possible ethos surrounding the Teotihuacan cult and beautifully preserved facade underlying later of war. construction. Although excavations were performed intermittently during the subsequent decades, some of The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the Tezcacoac the most important discoveries have occurred during the last several years. Recent investigations have Located in the rear center of the great Ciudadela revealed mass dedicatory burials in the foundations of compound, the Temple of Quetzalcoatl is one of the the Temple of Quetzalcoatl (Sugiyama 1989; Cabrera, largest pyramidal structures at Teotihuacan. In volume, Sugiyama, and Cowgill 1988); at the time of this it ranks only third after the Pyramid of the Moon and writing, more than eighty individuals have been the Pyramid of the Sun (Cowgill 1983: 322). As a result discovered interred in the foundations of the pyramid. of the Teotihuacan Mapping Project, it is now known Sugiyama (1989) persuasively argues that many of the that the Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the enclosing individuals appear to be either warriors or dressed in Ciudadela are located in the center of the ancient city the office of war. (Mill?n 1976: 236). The Ciudadela iswidely considered The archaeological investigations by Cabrera, to have been the seat of Teotihuacan rulership, and Sugiyama, and Cowgill are ongoing, and to comment held the palaces of the principal Teotihuacan lords extensively on the implications of their work would be (e.g., Armillas 1964: 307; Mill?n 1973: 55; Coe 1981: both premature and presumptuous. -

Breaking the Maya Code : Michael D. Coe Interview (Night Fire Films)

BREAKING THE MAYA CODE Transcript of filmed interview Complete interview transcripts at www.nightfirefilms.org MICHAEL D. COE Interviewed April 6 and 7, 2005 at his home in New Haven, Connecticut In the 1950s archaeologist Michael Coe was one of the pioneering investigators of the Olmec Civilization. He later made major contributions to Maya epigraphy and iconography. In more recent years he has studied the Khmer civilization of Cambodia. He is the Charles J. MacCurdy Professor of Anthropology, Emeritus at Yale University, and Curator Emeritus of the Anthropology collection of Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. He is the author of Breaking the Maya Code and numerous other books including The Maya Scribe and His World, The Maya and Angkor and the Khmer Civilization. In this interview he discusses: The nature of writing systems The origin of Maya writing The role of writing and scribes in Maya culture The status of Maya writing at the time of the Spanish conquest The impact for good and ill of Bishop Landa The persistence of scribal activity in the books of Chilam Balam and the Caste War Letters Early exploration in the Maya region and early publication of Maya texts The work of Constantine Rafinesque, Stephens and Catherwood, de Bourbourg, Ernst Förstemann, and Alfred Maudslay The Maya Corpus Project Cyrus Thomas Sylvanus Morley and the Carnegie Projects Eric Thompson Hermann Beyer Yuri Knorosov Tania Proskouriakoff His own early involvement with study of the Maya and the Olmec His personal relationship with Yuri -

Reassessing Shamanism and Animism in the Art and Archaeology of Ancient Mesoamerica

religions Article Reassessing Shamanism and Animism in the Art and Archaeology of Ancient Mesoamerica Eleanor Harrison-Buck 1,* and David A. Freidel 2 1 Department of Anthropology, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03824, USA 2 Department of Anthropology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63105, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Shamanism and animism have proven to be useful cross-cultural analytical tools for anthropology, particularly in religious studies. However, both concepts root in reductionist, social evolutionary theory and have been criticized for their vague and homogenizing rubric, an overly romanticized idealism, and the tendency to ‘other’ nonwestern peoples as ahistorical, apolitical, and irrational. The alternative has been a largely secular view of religion, favoring materialist processes of rationalization and “disenchantment.” Like any cross-cultural frame of reference, such terms are only informative when explicitly defined in local contexts using specific case studies. Here, we consider shamanism and animism in terms of ethnographic and archaeological evidence from Mesoamerica. We trace the intellectual history of these concepts and reassess shamanism and animism from a relational or ontological perspective, concluding that these terms are best understood as distinct ways of knowing the world and acquiring knowledge. We examine specific archaeological examples of masked spirit impersonations, as well as mirrors and other reflective materials used in divination. We consider not only the productive and affective energies of these enchanted materials, but also the Citation: Harrison-Buck, Eleanor, potentially dangerous, negative, or contested aspects of vital matter wielded in divinatory practices. and David A. Freidel. 2021. Reassessing Shamanism and Keywords: Mesoamerica; art and archaeology; shamanism; animism; Indigenous ontology; relational Animism in the Art and Archaeology theory; divination; spirit impersonation; material agency of Ancient Mesoamerica. -

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins by Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. The data collected links the Olmecs to other cultures in several areas such as writing, pottery and art. With this new found data two main theories have evolved. The first is that the Olmecs were the mother culture. This theory states that writing, the calendar and types of art originated under Olmec rule and later were spread to future generational tribes of Mesoamerica. The second main theory proposes that the Olmecs were one of many contemporary cultures all which acted sister cultures. The thought is that it was not the Olmecs who were the first to introduce writing or the calendar to Mesoamerica but that various indigenous surrounding tribes influenced and helped establish forms of writing, a calendar system and common types of art. -

Olmec Bloodletting: an Iconographic Study

Olmec Bloodletting: An Iconographic Study ROSEMARY A. JOYCE Peabody Museum, Harvard University RICHARD EDGING and KARL LORENZ University of Illinois, Urbana SUSAN D. GILLESPIE Illinois State University One of the most important of all Maya rituals was ceremonial bloodletting, either by drawing a cord through a hole in the tongue or by passing a stingray spine, pointed bone, or maguey thorn through the penis. Stingray spines used in the rite have often been found in Maya caches; in fact, so significant was this act among the Classic Maya that the perforator itself was worshipped as a god. This ritual must also have been frequently practiced among the earlier Olmec... Michael D. Coe in The Origins of Maya Civilization The iconography of bloodletting in the Early iconographic elements indicating autosacrifice, and Middle Formative (ca. 1200-500 B.C.) Olmec and glyphs referring to bloodletting. Most scenes symbol system is the focus of the present study.1 shown take place after the act of bloodletting and We have identified a series of symbols in large- include holding paraphernalia of autosacrifice, and small-scale stone objects and ceramics repre- visions of blood serpents enclosing ancestors, and senting perforators and a zoomorphic supernatural scattering blood in a ritual gesture. The parapher- associated with bloodletting. While aspects of nalia of bloodletting may also be held, not simply this iconography are comparable to later Classic as indications that an act of autosacrifice has Lowland Maya iconography of bloodletting, its taken place, but as royal regalia. Two elements deployment in public and private contexts dif- are common both in scenes of bloodletting and as fers, suggesting fundamental variation in the way royal regalia: the personified bloodletter, which bloodletting was related to political legitimation Coe (1977a:188) referred to as a god, and bands in the Formative Olmec and Classic Maya cases. -

Evenings for Educators 2017–18

^ Education Department Evenings for Educators Los Angeles County Museum of Art 5905 Wilshire Boulevard 2017–18 Los Angeles, California 90036 Resources Books for Students Online Resources Corn Is Maize: The Gift of the Indians Art of the Ancient Americas at LACMA Aliki Browse LACMA’s diverse collection of artwork from This book tells the story of how Native American the ancient Americas by time period or object type. farmers thousands of years ago found and nourished collections.lacma.org (Curatorial area/Art of the a wild grass plant and made corn an important part Ancient Americas) of their lives. Grades K–3 Digital Stories—Teotihuacan: City of Water, Descifrar el Cielo: La Astronomía en City of Fire Mesoamérica The de Young Museum in San Francisco created Federico Guzmán an online introduction to Teotihuacan that includes This Spanish-language book describes how the numerous images and maps of the city. Native communities of Mexico and Central America https://digitalstories.famsf.org/teo#start used their observations of the sky to develop agriculture, a precise calendar system, and advanced Related Curriculum Materials civilizations. Grades 6–12 Evenings for Educators resources include illustrated Here Is My Kingdom: Hispanic-American essays, discussion prompts for the classroom, Literature and Art for Young People and lesson plans for art-making activities. Browse Edited by Charles Sullivan selected online curriculum at lacma.org/students- Explore the multifaceted Hispanic-American/Latino teachers/teacher-resources. experience in this colorful anthology of poems, prose, and visual art. Grades K–12 Relevant curriculum materials include: Books for Teachers • Ancient Mexico: The Legacy of the Plumed Serpent • Olmec: Masterworks of Ancient Mexico An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya Mary Ellen Miller and Karl Taube Containing nearly 300 entries, this illustrated dictionary describes the mythology and religion of Mesoamerican cultures. -

University of Florida Thesis Or

SOCIAL COMPLEXITY IN FORMATIVE MESOAMERICA: A HOUSE-CENTERED APPROACH By CHIKAOMI TAKAHASHI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Chikaomi Takahashi 2 To my parents 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people. In particular, I would like to thank the members of my doctoral committee for their advice and guidance throughout this process of learning. I am very grateful to my advisor, Dr. Susan Gillespie, for all of her valuable guidance and encouragement to complete my study. She profoundly shaped my development as an anthropologist and an archaeologist, and reflective discussions with her influenced the directions I took in this research project. Dr. David Grove has been a fundamental influence in my intellectual development during my graduate study, especially in relation to my understanding of Formative Mesoamerica. Without his encouragement, ideas, and suggestions this dissertation would certainly not be what it is. The thoughtful reviews, comments and encouragements of Dr. Kenneth Sassaman and Dr. Mark Brenner are greatly appreciated. I am also very grateful to Dr. Andrew Balkansky who allowed me to join his Santa Cruz Tayata project and use necessary data for my dissertation. Without his generous support and thoughtful advice in the filed and the lab, I could not complete my research. I’m grateful to my friends in the Mixteca Alta whose support made my fieldwork enriching. Among the people of Tlaxiaco, I would like to specifically thank Mr.