60 the Identification of the West Wall Figures at Pinturas Sub-1, San

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds Mosley Dianna Wilson University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Wilson, Mosley Dianna, "Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 853. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/853 ANCIENT MAYA AFTERLIFE ICONOGRAPHY: TRAVELING BETWEEN WORLDS by DIANNA WILSON MOSLEY B.A. University of Central Florida, 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Liberal Studies in the College of Graduate Studies at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2006 i ABSTRACT The ancient Maya afterlife is a rich and voluminous topic. Unfortunately, much of the material currently utilized for interpretations about the ancient Maya comes from publications written after contact by the Spanish or from artifacts with no context, likely looted items. Both sources of information can be problematic and can skew interpretations. Cosmological tales documented after the Spanish invasion show evidence of the religious conversion that was underway. Noncontextual artifacts are often altered in order to make them more marketable. An example of an iconographic theme that is incorporated into the surviving media of the ancient Maya, but that is not mentioned in ethnographically-recorded myths or represented in the iconography from most noncontextual objects, are the “travelers”: a group of gods, humans, and animals who occupy a unique niche in the ancient Maya cosmology. -

Metaphors of Relative Elevation, Position and Ranking in Popol Vuh

METAPHORS OF RELATIVE ELEVATION, POSITION AND RANKING IN POPOL VUH Nathaniel TARN and Martin PRECHTEL Rutgers University This paper is an account of work very much in progress on the textual analysis of Popol V uh, and is one study among others (since this theme is attracting a number of students today) of inter-con nections and mutual illuminations between Popol Vuh and the con temporary ethnographic record in Highland Guatemala and Chiapas. For some considerable time now Popol Vuh has been considered as the major extant text of the Mesoamerican literary traditions, and as one of the most remarkable of all human creation stories, both for its beauty and for the complexity of its cosmological and mythical messages. While it may or may not have had a hieroglyphic original, the present alphabetic version of Po pol V uh wars written down some where between 1545 and 1558 by an anonymous member of the Cavek lineage of the Quiche Maya of Guatemala. This lineage had been a ruling house until it fell to the Spaniards in 1524. The manu script was copied by Francisco de Ximenez, a Spanish priest, some 150 years later. While there are references to Christianity in the text, these are few and it is generally regarded as one of the purest extant accounts of prehispanic Maya world-view. At the end of the hook, what we call mythical history shades into the historical history of the Quiche, so that the hook can serve as an illustration of the extent to which these two kinds of history are not held a,part by Maya generally. -

Panthéon Maya

Liste des divinités et des démons de la mythologie des mayas. Les noms sont tirés du Popol Vuh des Mayas Quichés, des livres de Chilam Balam et de Diego de Landa ainsi que des divers codex. Divinité Dieu Déesse Démon Monstre Animal Humain AB KIN XOC Dieu de poésie. ACAN Dieu des boissons fermentées et de l'ivresse. ACANTUN Quatre démons associés à une couleur et à un point cardinal. Ils sont présents lors du nouvel an maya et lors des cérémonies de sculpture des statues. ACAT Dieu des tatouages. AH CHICUM EK Autre nom de Xamen Ek. AH CHUY KAKA Dieu de la guerre connu sous le nom du "destructeur de feu". AH CUN CAN Dieu de la guerre connu comme le "charmeur de serpents". AH KINCHIL Dieu solaire (voir Kinich Ahau). AHAU CHAMAHEZ Un des deux dieux de la médecine. AHMAKIQ Dieu de l'agriculture qui enferma le vent quand il menaçait de détruire les récoltes. AH MUNCEN CAB Dieu du miel et des abeilles sans dard; il est patron des apiculteurs. AH MUN Dieu du maïs et de la végétation. AH PEKU Dieu du Tonnerre. AH PUCH ou AH CIMI ou AH CIZIN Dieu de la Mort qui régnait sur le Metnal, le neuvième niveau de l'inframonde. AH RAXA LAC DMieu de lYa Terre.THOLOGICA.FR AH RAXA TZEL Dieu du ciel AH TABAI Dieu de la Chasse. AH UUC TICAB Dieu de la Terre. 1 AHAU CHAMAHEZ Dieu de la Médecine et de la Guérison. AHAU KIN voir Kinich Ahau. AHOACATI Dieu de la Fertilité AHTOLTECAT Dieu des orfèvres. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

Sources and Resources/ Fuentes Y Recursos

ST. FRANCIS AND THE AMERICAS/ SAN FRANCISCO Y LAS AMÉRICAS: Sources and Resources/ Fuentes y Recursos Compiled by Gary Francisco Keller 1 Table of Contents Sources and Resources/Fuentes y Recursos .................................................. 6 CONTROLLABLE PRIMARY DIGITAL RESOURCES 6 Multimedia Compilation of Digital and Traditional Resources ........................ 11 PRIMARY RESOURCES 11 Multimedia Digital Resources ..................................................................... 13 AGGREGATORS OF CONTROLLABLE DIGITAL RESOURCES 13 ARCHIVES WORLDWIDE 13 Controllable Primary Digital Resources 15 European 15 Mexicano (Nahuatl) Related 16 Codices 16 Devotional Materials 20 Legal Documents 20 Maps 21 Various 22 Maya Related 22 Codices 22 Miscellanies 23 Mixtec Related 23 Otomi Related 24 Zapotec Related 24 Other Mesoamerican 24 Latin American, Colonial (EUROPEAN LANGUAGES) 25 PRIMARY RESOURCES IN PRINTED FORM 25 European 25 Colonial Latin American (GENERAL) 26 Codices 26 2 Historical Documents 26 Various 37 Mexicano (Nahautl) Related 38 Codices 38 Lienzo de Tlaxcala 44 Other Lienzos, Mapas, Tiras and Related 45 Linguistic Works 46 Literary Documents 46 Maps 47 Maya Related 48 Mixtec Related 56 Otomí Related 58 (SPREAD OUT NORTH OF MEXICO CITY, ALSO HIDALGO CLOSELY ASSOCIATED WITH THE OTOMÍ) Tarasco Related 59 (CLOSELY ASSOCIATED WITH MICHOACÁN. CAPITAL: TZINTZUNRZAN, LANGUAGE: PURÉPECHA) Zapotec Related 61 Other Mesoamerican 61 Latin American, Colonial (EUROPEAN LANGUAGES) 61 FRANCISCAN AND GENERAL CHRISTIAN DISCOURSE IN NATIVE -

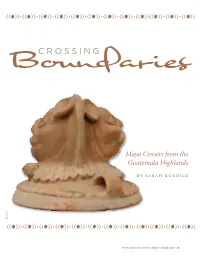

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

The Maya Vase Book

THE MAYA VASE BOOK THE HERO lWINS : MYfH AND IMAGE MICHAEL D. COE BACKGROUND heroes are inextricablywoven with those over his shoulders. After he had been ofgods, but also the charters for the elite duly baptized, and a Christian mass sung, I have been long puzzled by the curious groups which ruled these andent socie the K'ekchf drama began, to the sound of absence of any but the most cursory ties. Even today, throughout the Hindu shell trumpets, turtle carapaces, and other references to the Popol Yuh, the sacred Buddhist world of South and Southeast instruments. This was the Dance of bookoftheQuiche Maya, inEricThompson's Asia, the dynastic struggles of the Ma Hunahpu and Xbalanque, the Hero Twins, greatand encyclopedic Introduction to the habharata and the royal adventures of and theirdefeatofthe Lordsofthe Under Study oJ the Maya Hieroglyphs U950 and the Ramayana come alive in numberless world, Xibalba. latereditions). Surelyhemusthave noted shadow-puppet plays and ballets per the striking fact that in both Quiche and formed in both villages and royal courts. The performance opened with the ap Ixil, thenamefor the dayAhau, last ofthe Indeed, the actions ofKing Rama and his pearnnce oftwo youths in the plaza, wearing twentynamed days in the 260-daycount, monkey army in winning back his queen tight-fitting garments and great black is Hunahpu -- first-born ofthe Hero Twins. are as alive to Balinese children as events masks with horns. They proceeded to a Thompson was in many respects the ofmodern Indonesian political history. platform covered with clean mats and greatest Mayanist of all, with a deep adorned with artlfidal trees; a small knowledge of mythology and ethnohis Similar dramatic performances almost brushpile covered a hidden exit. -

The Mayan Gods: an Explanation from the Structures of Thought

Journal of Historical Archaeology & Anthropological Sciences Review Article Open Access The Mayan gods: an explanation from the structures of thought Abstract Volume 3 Issue 1 - 2018 This article explains the existence of the Classic and Post-classic Mayan gods through Laura Ibarra García the cognitive structure through which the Maya perceived and interpreted their world. Universidad de Guadalajara, Mexico This structure is none other than that built by every member of the human species during its early ontogenesis to interact with the outer world: the structure of action. Correspondence: Laura Ibarra García, Centro Universitario When this scheme is applied to the world’s interpretation, the phenomena in it and de Ciencias Sociales, Mexico, Tel 523336404456, the world as a whole appears as manifestations of a force that lies behind or within Email [email protected] all of them and which are perceived similarly to human subjects. This scheme, which finds application in the Mayan worldview, helps to understand the personality and Received: August 30, 2017 | Published: February 09, 2018 character of figures such as the solar god, the rain god, the sky god, the jaguar god and the gods of Venus. The application of the cognitive schema as driving logic also helps to understand the Maya established relationships between some animals, such as the jaguar and the rattlesnake and the highest deities. The study is part of the pioneering work that seeks to integrate the study of cognition development throughout history to the understanding of the historical and cultural manifestations of our country, especially of the Pre-Hispanic cultures. -

By ROBERT L. RANDS

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology BuUetin 157 Anthropological Papers, No. 48 Some ManifestatioDs of Water in Mesoamerican Art By ROBERT L. RANDS 265 1 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 27 The better established occurrences of water 273 Types of associations 273 The Maya codices 277 The Mexican codices 280 Aztec and Teotihuacdn murals, sculptures, and ceramics 285 Summary 291 The proposed identifications of water 292 Artistic approach to the identifications 292 Non-Maya murals, sculptures, and ceramics 293 Maya murals, sculptures, and ceramics 298 General considerations 298 Highest probability (A) 302 Probability B : paraphernalia and secondary associations 315 Probability B : fang, tongue, or water (?) 320 Artistic typology and miscellany 322 Water and the water lily 330 Conclusions 333 Appendix A. Nonartistic data and current reconstructions 342 Direct water associations : physiological data 342 Water from container 344 Water from mouth 348 Water from eye 348 Water from breast 350 Water from between legs 350 Water from body (pores ?) 350 Water from hand 352 Water from other object held in hand 354 Waterlike design from head 355 Glyph in water 365 Object in water 359 Tlaloc 359 Anthropomorphic Long-nosed God 359 Female water deity 369 Black god (M, B) 360 Miscellaneous anthropomorphic figures 360 Frog 360 Serpent 361 Jaguar (ocelot) 361 Bird 363 Miscellaneous animal 363 Serpentine-saurian monster 364 Detached rear head of monster 364 Other grotesque head, face 365 267 268 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY [Bull. 157 Appendix A. Nonartistic data and current reconstructions—Con. page Death, misfortune, destruction _. 365 Water descending on surface water 365 Water descending on figure 366 The bending-over rainmaker 366 The sky monster and its affiliates 366 Balanced water and vegetation 367 Summary 367 Appendix B. -

Manufactured Light Mirrors in the Mesoamerican Realm

Edited by Emiliano Gallaga M. and Marc G. Blainey MANUFACTURED MIRRORS IN THE LIGHT MESOAMERICAN REALM COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables xiii Chapter 1: Introduction Emiliano Gallaga M. 3 Chapter 2: How to Make a Pyrite Mirror: An Experimental Archaeology Project Emiliano Gallaga M. 25 Chapter 3: Manufacturing Techniques of Pyrite Inlays in Mesoamerica Emiliano Melgar, Emiliano Gallaga M., and Reyna Solis 51 Chapter 4: Domestic Production of Pyrite Mirrors at Cancuén,COPYRIGHTED Guatemala MATERIAL Brigitte KovacevichNOT FOR DISTRIBUTION73 Chapter 5: Identification and Use of Pyrite and Hematite at Teotihuacan Julie Gazzola, Sergio Gómez Chávez, and Thomas Calligaro 107 Chapter 6: On How Mirrors Would Have Been Employed in the Ancient Americas José J. Lunazzi 125 Chapter 7: Iron Pyrite Ornaments from Middle Formative Contexts in the Mascota Valley of Jalisco, Mexico: Description, Mesoamerican Relationships, and Probable Symbolic Significance Joseph B. Mountjoy 143 Chapter 8: Pre-Hispanic Iron-Ore Mirrors and Mosaics from Zacatecas Achim Lelgemann 161 Chapter 9: Techniques of Luminosity: Iron-Ore Mirrors and Entheogenic Shamanism among the Ancient Maya Marc G. Blainey 179 Chapter 10: Stones of Light: The Use of Crystals in Maya Divination John J. McGraw 207 Chapter 11: Reflecting on Exchange: Ancient Maya Mirrors beyond the Southeast Periphery Carrie L. Dennett and Marc G. Blainey 229 Chapter 12: Ritual Uses of Mirrors by the Wixaritari (Huichol Indians): Instruments of Reflexivity in Creative Processes COPYRIGHTEDOlivia Kindl MATERIAL 255 NOTChapter FOR 13: Through DISTRIBUTION a Glass, Brightly: Recent Investigations Concerning Mirrors and Scrying in Ancient and Contemporary Mesoamerica Karl Taube 285 List of Contributors 315 Index 317 vi contents 1 “Here is the Mirror of Galadriel,” she said. -

Runggaldier Curriculum Vitae August 2019

ASTRID M. RUNGGALDIER Department of Art and Art History, University of Texas at Austin 2301 San Jacinto Blvd., STOP D1300, ART 1.412C, Austin, TX 78712 Tel: 617-780-7826, [email protected] EDUCATION AND DEGREES Boston University, Department of Archaeology Boston MA • Ph.D. in Mesoamerican Archaeology, May 2009. Dissertation: Memory and Materiality in Monumental Architecture: Construction and Reuse of a Late Preclassic Maya Palace at San Bartolo, Guatemala (published by ProQuest/UMI, Ann Arbor, 2009. Publication No. AAT 3363637) • M.A. in Archaeology, Sept. 2002. Thesis: The Louisville Stuccoes: Recontextualizing Maya Architectural Sculptures from Northern Belize (published by BAR, Oxford, 2004) • B.A. in Archaeological Studies, Department of Archaeology; Minor in Geology, Department of Earth and Environment, January 1997 PROFESSIONAL RECORD HIGHER EDUCATION APPOINTMENTS: UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN, AUSTIN, TX 2012–PRESENT • Assistant Director of The Mesoamerica Center, Department of Art and Art History http://www.utmesoamerica.org/. Oversee current initiatives and develop new Center programming and special projects (including organizing yearly conferences and speaker series; updating website, social media and publications; collaborating with non-profit organizations; designing public outreach programs; and creating and implementing new digital initiatives for both campus Center and Casa Herrera in Guatemala); oversee budgets and financial procedures; manage all aspects of Casa Herrera including contracts, personnel, maintenance, -

Undergraduate Survey Project

PROYECTO ARQUEOLÓGICO REGIONAL SAN BARTOLO Proposal Acceptance Letter The undersigned, appointed by the Guatemalan Department of Archaeology, have examined a project proposal entitled “Xultun Tree, Mapping, and Excavation Project” presented by Alex Kara and hereby certify that it is worthy of acceptance. Signature______________________ Co-director William Saturno Signature______________________ Co-director Patricia Castillo Xultun Tree, Mapping, and Excavation Project an archaeological survey proposal by Alex Kara Boston University Boston, Massachusetts December 17th, 2012 Introduction The ancient Maya emerged from a dense tropical forest to establish a civilization that has long captivated the modern imagination. The Maya lowlands featured a population that numbed in the millions during its Classic Period fluorescence, which is impressive considering the seasonal droughts and lack of permanent, natural water sources that characterize the region. Prolific excavations of their urban centers have revealed much about ancient Maya culture, including their cosmological, artistic, political, and scientific institutions. On the other hand, comparatively little is known about larger Maya population dynamics or land use. The dense vegetation that characterizes this region prevents the kind of intensive archaeological survey that has revolutionized landscape archaeology in more arid regions during the late twentieth century. To further complicate studies of ancient demography, the soil in the Peten is usually very acidic; most organic matter, such as human and plant remains, does not appear the archaeological record. Despite these obstacles to studying the material remains of past societies at a large spatial scale, these broader questions cannot be ignored. Archaeology needs to dissect evidence of human behavior as completely as possible in any given environmental context, and local emphases on geographically convenient data types will skew holistic analyses of how things work.