An Analysis of Olmec Iconography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miguel Covarrubias

Miguel Covarrubias: An Inventory of the Adriana and Tom Williams Art Collection of Miguel Covarrubias at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Covarrubias, Miguel, 1904-1957 Title: Adriana and Tom Williams Art Collection of Miguel Covarrubias Dates: 1917-2006, undated Extent: 6 boxes, 12 flat file folders, 1 oversize print (184 items) Abstract: The Ransom Center's Adriana and Tom Williams Art Collection of Miguel Covarrubias is part of a larger collection of research material compiled by Covarrubias' biographer, Adriana Williams, and her husband Tom and is comprised of 169 original works and 15 posters. Call Number: Art Collection AR-00383 Language: English and Spanish Access: Open for research. Please note that a minimum of 24 hours notice is required to pull Art Collection materials to the Ransom Center's Reading and Viewing Room. Some materials may be restricted from viewing. To make an appointment or to reserve Art Collection materials, please contact the Center's staff at [email protected]. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. Use Policies: Ransom Center collections may contain material with sensitive or confidential information that is protected under federal or state right to privacy laws and regulations. Researchers are advised that the disclosure of certain information pertaining to identifiable living individuals represented in the collections without the consent of those individuals may have legal ramifications (e.g., a cause of action under common law for invasion of privacy may arise if facts concerning an individual's private life are published that would be deemed highly offensive to a reasonable person) for which the Ransom Center and The University of Texas at Austin assume no responsibility. -

The Olmec, Toltec, and Aztec

Mesoamerican Ancient Civilizations The Olmec, Toltec, and Aztec Olmecs of Teotihuacán -“The People of the Land of Rubber…” -Large stone heads -Art found throughout Mesoamerica Olmec Civilization Origin and Impact n The Olmec civilization was thought to have originated around 1500 BCE. Within the next three centuries of their arrival, the people built their capital at Teotihuacán n This ancient civilization was believed by some historians to be the Mother-culture and base of Mesoamerica. “The city may well be the basic civilization out of which developed such high art centers as those of Maya, Zapotecs, Toltecs, and Totonacs.” – Stirling Cultural Practices n The Olmec people would bind wooden planks to the heads of infants to create longer and flatter skulls. n A game was played with a rubber ball where any part of the body could be used except for hands. Religion and Art n The Olmecs believed that celestial phenomena such as the phases of the moon affected daily life. n They worshipped jaguars, were-jaguars, and sometimes snakes. n Artistic figurines and toys were found, consisting of a jaguar with a tube joining its front and back feet, with clay disks forming an early model of the wheel. n Large carved heads were found that were made from the Olmecs. Olmec Advancements n The Olmecs were the first of the Mesoamerican societies, and the first to cultivate corn. n They built pyramid type structures n The Olmecs were the first of the Mesoamerican civilizations to create a form of the wheel, though it was only used for toys. -

The Archaeology of Early Formative Chalcatzingo, Morelos, Mexico, 1995

FAMSI © 2000: Maria Aviles The Archaeology of Early Formative Chalcatzingo, Morelos, México, 1995 Research Year : 1995 Culture: Olmec Chronology: Early Pre-Classic Location: Morelos, México Site: Chalcatzingo Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Introduction Results of Field Investigations Excavations of the Platform Mound Excavation of the Test Units Excavation of New Monument Results of Laboratory Investigations Conclusion: Significance of Research and Future Plans List of Figures Sources Cited Abstract This research project reports on the earliest monumental constructions at the site of Chalcatzingo, Morelos. The site of Chalcatzingo, located 120 kilometers southeast of México City in the state of Morelos, is situated at the base of two large hills on the only good expanse of agricultural land for many miles. Resumen Este proyecto de investigación informa sobre las construcciones monumentales más tempranas en el sitio de Chalcatzingo, Morelos. El sitio de Chalcatzingo, ubicado a 120 kilómetros al sureste de la Ciudad de México en el estado de Morelos, está situado en la base de dos colinas grandes en la única extensión de tierra agrícola buena por muchas millas. Submitted 12/01/1997 by: Maria Aviles Introduction Monumental architecture, consisting of earthen platform mounds sometimes faced with stone, began appearing in Mesoamerica around 1300 B.C. during the Early Formative Period (1500-900 B.C.). Monumental architecture has been identified at several sites, but rarely in Central México, a region which later saw the first development of urbanism and the largest pyramids in México. This research project reports on the earliest monumental constructions at the site of Chalcatzingo, Morelos. The site of Chalcatzingo, located 120 kilometers southeast of México City in the state of Morelos, is situated at the base of two large hills on the only good expanse of agricultural land for many miles ( Figure 1 ). -

Olmec Mirrors: an Example of Archaeological American Mirrors

1 Olmec mirrors: an example of archaeological American mirrors José J. Lunazzi Universidade Estadual de Campinas - Instituto de Física 13083-970 - Campinas - SP - Brazil [email protected] ABSTRACT Archaeological mirrors from the Olmec civilization are described according to bibliographic references and to personal observations and photographs. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. APPEARANCE OF THE MIRRORS 3. HOW TO FIND THEM 4. THEIR SIGNIFICANCE IN THE CULTURAL CONTEXT OF THE OLMECS 5. TYPES OF MIRRORS 6. ON THE QUALITY OF REFRACTIVE ELEMENTS 7. CONCLUSIONS 8. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 9. REFERENCES 2 1. INTRODUCTION This report was not intended to give all the available information on the subject, but just a simple description that may be valuable for improving the knowledge that the optical community may have on it. The author believes to have consulted most of the available scientific bibliography as it can be traced through cross-referencing from the most recent papers. Olmec mirrors are the most ancient archaeological mirrors from Mexico and constitute a very good example of ancient American mirrors. The oldest mirrors found in America are from the Incas, made about 800 years before the Olmecs, dated from findings in archaeological sites in Peru. How this technology would have been extended to the north, appearing within the Olmecs, later within the Teotihuacan civilization, a few centuries before the Spanish colonization, is an interesting matter. Mirrors are important also within the Aztec civilization, that appeared in the proximity of the Olmec and Teotihuacan domains at about the time of their extintion. The extension of the geographic area where these mirrors were employed seems to us not entirely well-known. -

Religious Advisement Resources Part Ii

RELIGIOUS ADVISEMENT RESOURCES 2020 PART II Notice Regarding External Resources: The listed resources are provided in this document are operated by other government organizations, commercial firms, educational institutions, and private parties. We have no control over the information of these resources which may contain information that could be objectionable or which may not otherwise conform to Department of Defense policies. These listings are offered as a convenience and for informational purposes only. Their inclusion here does not constitute an endorsement or an approval by the Department of Defense of any of the products, services, or opinions of the external providers. The Department of Defense bears no responsibility for the accuracy or the content of these resources. 1 FAITH AND BELIEF SYSTEMS U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Religious Beliefs and Practices http://www.acfsa.org/documents/dietsReligious/FederalGuidelinesInmateReligiousBeliefsandPractices032702.pdf Buddhism Native American Eastern Rite Catholicism Odinism/Asatru Hinduism Protestant Christianity Islam Rastfari Judaism Roman Catholic Christianity Moorish Science Temple of America Sikh Dharma Nation of Islam Wicca U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Religious Literacy Primer https://crcc.usc.edu/files/2015/02/Primer-HighRes.pdf Baha’i Earth-Based Spirituality Buddhism Hinduism Christianity: Anabaptist Humanism Anglican/Episcopal Islam Christian Science Jainism Evangelical Judaism Jehovah’s Witnesses -

ATLANTE 3-Manuel Álvarez Bravo

1 Manuel Álvarez Bravo et la photographie contemporaine Nus, plantes, paysages Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Fruit défendu (1976) © Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, SC Coordination Paul-Henri Giraud Atlante. Revue d’études romanes, automne 2015 2 Paul-Henri GIRAUD Imprévisible profondeur du visible. En guise d’avant-propos 4 Dossier José Antonio RODRIGUEZ La buena fama durmiendo: otro acercamiento 18 Jacques TERRASA Chevelures et pilosités dans l’œuvre de Manuel Álvarez Bravo 25 Juan Carlos BAEZA SOTO Écorcher l’absolu. Corps et identité de l’âme dans les nus de Manuel Álvarez Bravo 48 Daniel HAUTELIN Patience, obstination, révélation. Manuel Álvarez Bravo et Bertrand Hugues face au monde végétal 80 Annexes Vivienne Silver Manuel Álvarez Bravo. Clefs pour une œuvre 104 (Traduction de « A Guide to Viewing Manuel Alvarez Bravo », Exposure, 19:2, 1981, p. 42-49, par les étudiants du parcours « Traduction juridique et technique (JET) » du Master « Métiers du Lexique et de la Traduction (français-anglais) – MéLexTra » de l’Université Lille 3, promotion 2015-2016). Paul-Henri Giraud “Trato de simplificar al máximo lo representado” Entrevista con el fotógrafo Rafael Navarro 119 Paul-Henri Giraud « J’essaye de simplifier au maximum ce qui est représenté » Entretien avec le photographe Rafael Navarro (traduit par P.-H. Giraud) 125 Jacques Terrasa Micropaysages, portraits, nus Entretien avec le photographe Pierre-Jean Amar 131 Atlante. Revue d’études romanes, automne 2015 3 Eduardo Ramos-Izquierdo Suite de desnudos femeninos 147 Marcos Zimmermann Un encuentro con Manuel Álvarez Bravo en Arles y su Colección para la Fundación Televisa 153 Marcos Zimmermann Une rencontre avec Manuel Álvarez Bravo en Arles et sa Collection pour la Fundación Televisa (traduit par Michèle Guillemont) 156 Marcos Zimmermann Desnudos sudamericanos 159 Marcos Zimmermann Nus sud-américains (traduit par Michèle Guillemont) 165 Compte rendu Michele Carini Sur Promessi sposi d’autore. -

Problems in Interpreting the Form and Meaning of Mesoamerican Tomple Platforms

Problems in Interpreting the Form and Meaning of Mesoamerican Tomple Platforms Richard 8. Wright Perhaps the primary fascination of Pre-Columbian art the world is founded and ordered, it acquires meaning. We for art historians lies in the congruence of image and con can then have a sense of place in it. " 2 cept; lacking a widely-used fonn of written language, art In lhe case of the Pyramid of lhe Sun, its western face fonns were employed to express significant concepts, often is parallel to the city's most prominent axis, the avenue to peoples of different languages. popularly known as the Street of the Dead. Tllis axis is Such an extremely logographic role for art should oriented 15°28' east of true nonh for some (as yet) un condition research in a fundamental way. For example, to defined reason (although many other Mesoamcriean sites the extent that Me.wamerican an-fonns literally embody have similar orientations). Offered in explanation arc a concepts, !here can be no real separation of image and variety of hypotheses that often intenningle calendrical, meaning. To interpret such an in the Jjght of Western topographical and celestial elements.' conventions, where meaning can be indirectly perceived (as It should not be surprising to see similar practices in in allegory or the imitation of nature), is to project mislead other Mesoamerican centers, given the religious con• ing expectations which !hen hinder understanding. servatism of ancient cultures in general. Through the One of the most obvious blendings of form and common orientations and orientation techniques of many meaning in Pre-Columbian art is the temple, with its Mesoamerican sites, we can detect specific manifestations supponing platfonn. -

The Blue House: the Intimate Universe of Frida Kahlo

The Blue House: The Intimate Universe of Frida Kahlo “Never in life will I forget your presence. You found me torn apart and you took me back full and complete.” Frida Kahlo By delving into the knowledge of Frida Kahlo's legacy, one discovers the intense relationship that exists between Frida, her work and her home. Her creative universe is to be found in the Blue House, the place where she was born and where she died. Following her marriage to Diego Rivera, Frida lived in different places in Mexico City and abroad, but she always returned to her family home in Coyoacan. Located in one of the oldest and most beautiful neighborhoods in Mexico City, the Blue House was made into a museum in 1958, four years after the death of the painter. Today it is one of the most visited museums in the Mexican capital. Popularly known as the Casa Azul (the ‘Blue House’), the Museo Frida Kahlo preserves the personal objects that reveal the private universe of Latin America’s most celebrated woman artist. The Blue House also contains some of the painter’s most important works: Long Live Life (1954), Frida and the Caesarian Operation (1931), and Portrait of My Father Wilhelm Kahlo (1952), among others. In the room she used during the day is the bed with the mirror on the ceiling, set up by her mother after the bus accident in which Frida was involved on her way home from the National Preparatory School. During her long convalescence, while she was bedridden for nine months, Frida began to paint portraits. -

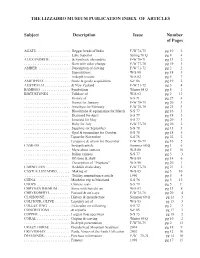

List of Articles

THE LIZZADRO MUSEUM PUBLICATION INDEX OF ARTICLES Subject Description Issue Number of Pages AGATE. .. Beggar beads of India F-W 74-75 pg 10 2 . Lake Superior Spring 70 Q pg 8 4 ALEXANDRITE . & Synthetic alexandrite F-W 70-71 pg 13 2 . Gem with color change F-W 77-78 pg 19 1 AMBER . Description of carving F-W 71-72 pg 2 2 . Superstitions W-S 80 pg 18 5 . in depth treatise W-S 82 pg 5 7 AMETHYST . Stone & geode acquisitions S-F 86 pg 19 2 AUSTRALIA . & New Zealand F-W 71-72 pg 3 4 BAMBOO . Symbolism Winter 68 Q pg 8 1 BIRTHSTONES . Folklore of W-S 93 pg 2 13 . History of S-S 71 pg 27 4 . Garnet for January F-W 78-79 pg 20 3 . Amethyst for February F-W 78-79 pg 22 3 . Bloodstone & aquamarine for March S-S 77 pg 16 3 . Diamond for April S-S 77 pg 18 3 . Emerald for May S-S 77 pg 20 3 . Ruby for July F-W 77-78 pg 20 2 . Sapphire for September S-S 78 pg 15 3 . Opal & tourmaline for October S-S 78 pg 18 5 . Topaz for November S-S 78 pg 22 2 . Turquoise & zircon for December F-W 78-79 pg 16 5 CAMEOS . In-depth article Summer 68 Q pg 1 6 . More about cameos W-S 80 pg 5 10 . Italian cameos S-S 77 pg 3 3 . Of stone & shell W-S 89 pg 14 6 . Description of “Neptune” W-S 90 pg 20 1 CARNELIAN . -

Chalcatzingo:Abrief Introduction Special DAVID C

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute Volume IX, No. 1, Summer 2008 Chalcatzingo:ABrief Introduction Special DAVID C. GROVE Chalcatzingo Issue University of Florida containing: In 1934 archaeologist Eulalia Guzmán trav- bas-relief carvings. The largest of them Chalcatzingo: A eled to the remote hamlet of Chalcatzingo (Monument 1), nicknamed “El Rey” by Brief Introduction near Jonacatepec in the Amatzinac valley the villagers, depicts a personage seated of eastern Morelos state to investigate re- in a cave-like niche above which are rain by ports of “stones with reliefs.” The village clouds and falling raindrops (Guzmán David Grove sits near two conjoined granodiorite hills 1934:Fig. 3) (Figure 2). In addition, in a PAGES 1-7 or cerros—the Cerro Delgado and the larg- small barranca that cuts through the site er Cerro Chalcatzingo (also known as the Guzmán was shown a unique three di- • Cerro de la Cantera)—that jut out starkly mensional sculpture—a “mutilated stat- against the relatively flat landscape of the ue” of a seated personage, minus its head. Chalcatzingo valley (Figure 1). The archaeological site Guzmán also found pot sherds dating to Monument 34: A that Guzmán viewed is situated just at both the “Archaic” (Preclassic or Forma- Formative Period the base of those cerros where they meet tive) and “Teotihuacan” (Classic) periods, “Southern Style” to form a V-shaped cleft. The ancient oc- leaving her uncertain as to the date of the Stela in the Central cupation extended across a series of ter- carvings (Grove 1987c:1). Mexican Highlands races below the twin cerros. -

A Mat of Serpents: Aztec Strategies of Control from an Empire in Decline

A Mat of Serpents: Aztec Strategies of Control from an Empire in Decline Jerónimo Reyes On my honor, Professors Andrea Lepage and Elliot King mark the only aid to this thesis. “… the ruler sits on the serpent mat, and the crown and the skull in front of him indicate… that if he maintained his place on the mat, the reward was rulership, and if he lost control, the result was death.” - Aztec rulership metaphor1 1 Emily Umberger, " The Metaphorical Underpinnings of Aztec History: The Case of the 1473 Civil War," Ancient Mesoamerica 18, 1 (2007): 18. I dedicate this thesis to my mom, my sister, and my brother for teaching me what family is, to Professor Andrea Lepage for helping me learn about my people, to Professors George Bent, and Melissa Kerin for giving me the words necessary to find my voice, and to everyone and anyone finding their identity within the self and the other. Table of Contents List of Illustrations ………………………………………………………………… page 5 Introduction: Threads Become Tapestry ………………………………………… page 6 Chapter I: The Sum of its Parts ………………………………………………… page 15 Chapter II: Commodification ………………………………………………… page 25 Commodification of History ………………………………………… page 28 Commodification of Religion ………………………………………… page 34 Commodification of the People ………………………………………… page 44 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………... page 53 Illustrations ……………………………………………………………………... page 54 Appendices ……………………………………………………………………... page 58 Bibliography ……………………………………………………………………... page 60 …. List of Illustrations Figure 1: Statue of Coatlicue, Late Period, 1439 (disputed) Figure 2: Peasant Ritual Figurines, Date Unknown Figure 3: Tula Warrior Figure Figure 4: Mexica copy of Tula Warrior Figure, Late Aztec Period Figure 5: Coyolxauhqui Stone, Late Aztec Period, 1473 Figure 6: Male Coyolxauhqui, carving on greenstone pendant, found in cache beneath the Coyolxauhqui Stone, Date Unknown Figure 7: Vessel with Tezcatlipoca Relief, Late Aztec Period, ca. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Modern Monumentality: Art, Science, and the Making of Southern Mexico Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2fg292mm Author Kett, Robert John Publication Date 2015 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2fg292mm#supplemental Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Modern Monumentality: Art, Science, and the Making of Southern Mexico DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Anthropology by Robert John Kett Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Mei Zhan, Chair Professor George Marcus Professor Bill Maurer Associate Professor Rachel O’Toole 2015 Earlier version of Chapter 1 © 2014 California Academy of Sciences Earlier version of Chapter 5 © 2015 University of California Press All other material © 2015 Robert John Kett Dedication For Sue, Dwight, and Albert and in memory of Bob and Peggy. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 Ornithologists in Olman: Epistemological Ecologies in the Field and the Museum 20 CHAPTER 2 Pan-American Itineraries: Incorporating the Southern Mexican Frontier 44 CHAPTER 3 Modern Frictions: Plays for Territory at La Venta 74 CHAPTER 4 Monumentality as Method: Archaeology and Land Art in the Cold War 103 CHAPTER 5 Archiving Oil: The Practice and Politics of Information 142 BIBLIOGRAPHY 171 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation has benefitted from the kindness of many mentors, friends, family members, and collaborators. I would first like to thank my advisor, Mei Zhan, for being such a sympathetic guide during the conception and execution of this project.