The PARI Journal Vol. XII, No. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Importance of La Corona1 Marcello A

La Corona Notes 1(1) The Importance of La Corona1 Marcello A. Canuto Middle American Research Institute / Tulane University Tomás Barrientos Q. Universidad del Valle de Guatemala In 2008, the Proyecto Regional Arqueológico monuments led to the realization that these texts La Corona (PRALC; directed by Marcello A. contained several terms not only common in, but Canuto and Tomás Barrientos Q.) was established also unique to the texts of Site Q (Stuart 2001). to coordinate archaeological research in the The locative term thought to be the ancient Maya northwestern sector of the Guatemalan Peten. name of Site Q (sak nikte’), the name of a Site Q ruler Centered at the site of La Corona (N17.52 W90.38), (Chak Ak’aach Yuk), titles characteristic of Site Q PRALC initiated the first long-term scientific rulers (sak wayis), and references to Site Q’s most research of both the site and the surrounding important ally (Kaanal), were all present in the region. To a large extent, however, La Corona texts found at La Corona. Despite expressed doubts was well known long before PRALC began its regarding the identification of La Corona as Site Q investigations, since it was ultimately revealed to (Graham 2002), petrographic similarities between be the mysterious “Site Q.” As the origin of over stone samples from a Site Q monument and from two dozen hieroglyphic panels looted in the 1960s exemplars collected at the site of La Corona led and attributed to the as-yet-unidentified “Site Q” Stuart (2001) to suggest that La Corona was Site Q. -

With the Protection of the Gods: an Interpretation of the Protector Figure in Classic Maya Iconography

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography Tiffany M. Lindley University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lindley, Tiffany M., "With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2148. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2148 WITH THE PROTECTION OF THE GODS: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE PROTECTOR FIGURE IN CLASSIC MAYA ICONOGRAPHY by TIFFANY M. LINDLEY B.A. University of Alabama, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 © 2012 Tiffany M. Lindley ii ABSTRACT Iconography encapsulates the cultural knowledge of a civilization. The ancient Maya of Mesoamerica utilized iconography to express ideological beliefs, as well as political events and histories. An ideology heavily based on the presence of an Otherworld is visible in elaborate Maya iconography. Motifs and themes can be manipulated to convey different meanings based on context. -

Investigaciones Arqueológicas En La Región De Holmul, Petén: Cival, Y K’O

INVESTIGACIONES ARQUEOLÓGICAS EN LA REGIÓN DE HOLMUL, PETÉN: CIVAL, Y K’O. INFORME PRELIMINAR DE LA TEMPORADA 2008 Francisco Estrada-Belli, Director Pendiente en forma de hacha-efigie del dios Chaak. Cival, ofrenda CIV.T.64.05. Preclásico Tardío Proyecto Arqueológico Holmul Boston University Archaeology Department 675 Commonwealth Avenue Boston MA 02215 Email: [email protected] URL http://www.bu.edu/holmul/reports/informe_08_layout.pdf Informe Proyecto Holmul 2008 INDICE Capitulo 1 Resumen de la temporada de campo de 2008 del Proyecto Arqueológico Holmul................................................................................................................................ 7 Capitulo 2 Hill Group 45 CIV.L. 03.............................................................................. 21 Capitulo 3 Hill-Group 10 CIV.T.53 ............................................................................. 22 Capitulo 4 Hill Group 45 CIV.T.51............................................................................... 26 Capitulo 5 Hill Group 38................................................................................................ 31 Capitulo 6 Hill Group 45 L.01 ....................................................................................... 35 Capitulo 7 Hill Group 4 L. 04 ........................................................................................ 36 Capitulo 8 Hill Group 36 CIV.T. 62.............................................................................. 37 Capitulo 9 Hill Group 37, Excavación CIV.T. -

Universidad De San Carlos De Guatemala Escuela De Historia Carrera De Arqueología

UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA ESCUELA DE HISTORIA CARRERA DE ARQUEOLOGÍA “Hunahpu, un complejo conmemorativo del Preclásico Medio del sitio arqueológico San Bartolo, Flores, Petén” BORIS FERNANDO BELTRÁN MORÁN Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción, Guatemala, C.A. Septiembre de 2015 UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA ESCUELA DE HISTORIA CARRERA DE ARQUEOLOGÍA “Hunahpu, un complejo conmemorativo del Preclásico Medio del sitio arqueológico San Bartolo, Flores, Petén” T E S I S Presentada por: BORIS FERNANDO BELTRÁN MORÁN Previo a conferírsele el título de ARQUEÓLOGO En el grado académico de: LICENCIADO Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción, Guatemala, C.A. Septiembre de 2015 UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA ESCUELA DE HISTORIA AUTORIDADES UNIVERSITARIAS RECTOR: Dr. Carlos Guillermo Alvarado Cerezo SECRETARIO: Dr. Carlos Camey AUTORIDADES DE LA ESCUELA DE HISTORIA DIRECTOR: Dra. Artemis Torres Valenzuela SECRETARIO: Licda. Olga Pérez CONSEJO DIRECTIVO DIRECTOR: Dra. Artemis Torres Valenzuela SECRETARIO: Licda. Olga Pérez VOCAL I: Dra. Tania Sagastume VOCAL II: Licda. María Laura Jiménez Chacón VOCAL III: Licda. Zoila Rodríguez Girón VOCAL IV: Amalia Judith Tzunux Sanic VOCAL V: Byron Anderson Chivalán ASESORA DE TESIS Licda. Mónica Claudina Urquizú Sánchez COMITÉ DE TESIS Dr. Héctor Escobedo Lic. Héctor Mejía “Los autores serán responsables de las opiniones o criterios expresados en su obra”. Capítulo V, Arto. 11 del Reglamento del Consejo Editorial de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Dedicatoria A mis Padres Fernando Beltrán y Reginalda Morán (+) por guiarme en la vida, enseñarme a dar sin esperar recibir, de hacer cosas buenas porque a la postre vendrán cosas buenas y a disfrutar de lo maravilloso que es compartir la vida sin importar la situación. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

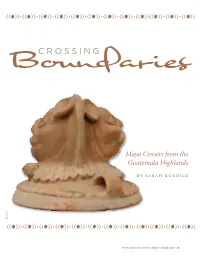

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

The PARI Journal Vol. IV, No. 4

The PARI Journal A quarterly publication of the Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute Volume IV, No 4, Spring 2004 In This Issue: Glyphs for “Handspan” and “Strike” in Glyphs for “Handspan” and Classic Maya Ballgame Texts1 “Strike” in Classic Maya Ballgame Texts MARC ZENDER Peabody Museum, Harvard University by Marc Zender PAGES 1-9 • Part ritual, part recreation, and almost wholly mysterious, the ancient Maya ballgame has Sport, Spectacle long been regarded as an enigmatic entity. Literally dozens of ballcourts are known; untold and Political hundreds of pieces of ballgame paraphernalia are housed in Museums; and yet we know Theater: frustratingly little for certain about the rules of the ancient game, its purpose or its origins. New Views of Recently, however, the veil of obscurity has begun to lift from these most intriguing of all the Classic Maya relics of the Mesoamerican past. Archaeological investigations have revealed the construc- Ballgame tion history of ballcourts, disclosing their Preclassic origins and convincingly embedding by Marc Zender them in cultural, historical and political trajectories of which they form an integral part. PAGES 10-12 Further, anthropologists’ and historians’ diligent sifting of ethnohistoric documents and • careful comparison with surviving ballgame traditions have begun to reveal something of Return to the the rules, purpose and underlying rationale of the game. Great Forests The aim of this paper is to further refine our understanding of Classic Maya ballgames Frans Blom's (ca. A.D. 250-900) through an exploration of two previously undeciphered logographs. The Letters from first represents a right hand shown palm down and with thumb and forefinger spread Palenque: (Figures 1b, 1c, 5a and 5b). -

11 UNDER the RULE of the SNAKE KINGS: UXUL in the 7TH and 8TH Centuries*

UNDER THE RULE OF THE SNAKE KINGS: UXUL IN THE 7th AND 8th CENTURIES Nikolai Gru B E Kai Del V endahl Nicolaus Seefeld Uxul Archaeological Project Universität Bonn Benia M ino Volta Department of Anthropology, University of California-San Diego RESUMEN : Desde el 2009, la Universidad de Bonn efectúa trabajos arqueológicos en el sitio de Uxul, una ciudad maya del Clásico en el extremo sur del estado de Campeche. El objetivo del proyecto es investigar la expansión y desintegración de los poderes hegemónicos en el área maya, con un enfoque en la zona central de las Tierras Bajas y específicamente en la estrecha relación de Uxul con los gobernantes de la poderosa dinastía Kaan de Calakmul. Evidencia novedosa confirma las hipótesis de que Uxul estuvo bajo control de Calakmul en el siglo V ii y de que su caída se puede relacionar directamente con las derrotas de los gobernantes Yukno’m Yich’aak K’ahk’ y Yukno’m Took’ K’awiil a cargo de Tikal en 695 y 736 d. C., respec- tivamente. Cuando las autoridades centrales colapsaron en la segunda mitad del siglo Viii, la población de Uxul ni siquiera fue capaz de mantener la infraestructura más importante para sobrevivir: aquella relacionada con el manejo del agua. PALAB R AS CLAVE : Uxul, Calakmul, palacio real, manejo de agua, colapso. ABST R ACT : Since 2009, the University of Bonn is conducting archaeological investigations at Uxul, a medium sized classic Maya city in the extreme south of the Mexican state of Campeche. The project’s research goal is to investigate the expansion and disintegration of hegemonic power in the Maya area, concentrating on the core area of the Maya Lowlands and especially on Uxul’s close relation to the powerful Kaan dynasty at Calakmul. -

Architecture at San Bartolo, El Peten, Guatemala: Object and Subject

Originalni nauni rad UDK: 72.031.2(=821.173)(728.1) 1 Sanja Savki& Belgrade, Serbia ARCHITECTURE AT SAN BARTOLO, EL PETEN, GUATEMALA: OBJECT AND SUBJECT Abstract: Certain ancient Maya architectural patterns had multiple meanings and symbolic functions. They were designed not simply as static monuments to demon- strate the power of their patrons, but as places for the performance of transcendent events that linked those rulers to their constituencies – ancestors and gods likewise. Moreover, when ritually activated, they could acquire existential status, by providing the object with agency, meaning, and its own point of view, thus annulling the su- bject-object dichotomy, which is in accordance with the magical-mythic beliefs of their makers. At San Bartolo, located in the north-east of the Guatemalan state El Pe- ten, around the year 100 BC there was an architectural complex that incarnated some Maya ideas regarding the universe, its cosmogony, and the role of the human beings. Key words: San Bartolo, Maya architecture, existential status of images, mountain- cave complex, quatrefoil motif. The objective of this paper2 is to substantiate that the sixth architectural pha- se3 (of eight in total) of Las Pinturas Pyramid4 or Structure 1 (ca. 100 BC) at San Bartolo, located in Guatemalan state of El Peten, can be interpreted as a co- smogram which displays the ancient Maya conceptualization of space materiali- zed in a particular architectural pattern. This cosmogram refers to the spatial or- dering of the universe in three levels (as seen vertically), perceived as the under- world, the Earth’s surface, and the upper or celestial world. -

Manufactured Light Mirrors in the Mesoamerican Realm

Edited by Emiliano Gallaga M. and Marc G. Blainey MANUFACTURED MIRRORS IN THE LIGHT MESOAMERICAN REALM COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables xiii Chapter 1: Introduction Emiliano Gallaga M. 3 Chapter 2: How to Make a Pyrite Mirror: An Experimental Archaeology Project Emiliano Gallaga M. 25 Chapter 3: Manufacturing Techniques of Pyrite Inlays in Mesoamerica Emiliano Melgar, Emiliano Gallaga M., and Reyna Solis 51 Chapter 4: Domestic Production of Pyrite Mirrors at Cancuén,COPYRIGHTED Guatemala MATERIAL Brigitte KovacevichNOT FOR DISTRIBUTION73 Chapter 5: Identification and Use of Pyrite and Hematite at Teotihuacan Julie Gazzola, Sergio Gómez Chávez, and Thomas Calligaro 107 Chapter 6: On How Mirrors Would Have Been Employed in the Ancient Americas José J. Lunazzi 125 Chapter 7: Iron Pyrite Ornaments from Middle Formative Contexts in the Mascota Valley of Jalisco, Mexico: Description, Mesoamerican Relationships, and Probable Symbolic Significance Joseph B. Mountjoy 143 Chapter 8: Pre-Hispanic Iron-Ore Mirrors and Mosaics from Zacatecas Achim Lelgemann 161 Chapter 9: Techniques of Luminosity: Iron-Ore Mirrors and Entheogenic Shamanism among the Ancient Maya Marc G. Blainey 179 Chapter 10: Stones of Light: The Use of Crystals in Maya Divination John J. McGraw 207 Chapter 11: Reflecting on Exchange: Ancient Maya Mirrors beyond the Southeast Periphery Carrie L. Dennett and Marc G. Blainey 229 Chapter 12: Ritual Uses of Mirrors by the Wixaritari (Huichol Indians): Instruments of Reflexivity in Creative Processes COPYRIGHTEDOlivia Kindl MATERIAL 255 NOTChapter FOR 13: Through DISTRIBUTION a Glass, Brightly: Recent Investigations Concerning Mirrors and Scrying in Ancient and Contemporary Mesoamerica Karl Taube 285 List of Contributors 315 Index 317 vi contents 1 “Here is the Mirror of Galadriel,” she said. -

High-Precision Radiocarbon Dating of Political Collapse and Dynastic Origins at the Maya Site of Ceibal, Guatemala

High-precision radiocarbon dating of political collapse and dynastic origins at the Maya site of Ceibal, Guatemala Takeshi Inomata (猪俣 健)a,1, Daniela Triadana, Jessica MacLellana, Melissa Burhama, Kazuo Aoyama (青山 和夫)b, Juan Manuel Palomoa, Hitoshi Yonenobu (米延 仁志)c, Flory Pinzónd, and Hiroo Nasu (那須 浩郎)e aSchool of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0030; bFaculty of Humanities, Ibaraki University, Mito, 310-8512, Japan; cGraduate School of Education, Naruto University of Education, Naruto, 772-8502, Japan; dCeibal-Petexbatun Archaeological Project, Guatemala City, 01005, Guatemala; and eSchool of Advanced Sciences, Graduate University for Advanced Studies, Hayama, 240-0193, Japan Edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff, Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, NM, and approved December 19, 2016 (received for review October 30, 2016) The lowland Maya site of Ceibal, Guatemala, had a long history of resolution chronology may reveal a sequence of rapid transformations occupation, spanning from the Middle Preclassic period through that are comprised within what appears to be a slow, gradual transi- the Terminal Classic (1000 BC to AD 950). The Ceibal-Petexbatun tion. Such a detailed understanding can provide critical insights into Archaeological Project has been conducting archaeological inves- the nature of the social changes. Our intensive archaeological inves- tigations at this site since 2005 and has obtained 154 radiocarbon tigations at the center of Ceibal, Guatemala, have produced 154 ra- dates, which represent the largest collection of radiocarbon assays diocarbon dates, which represent the largest set of radiocarbon assays from a single Maya site. The Bayesian analysis of these dates, ever collected at a Maya site. -

59 San Bartolo, Petén: Late Preclassic Techniques Of

59 SAN BARTOLO, PETÉN: LATE PRECLASSIC TECHNIQUES OF MURAL PAINTING Heather Hurst Keywords: Maya archaeology, Maya art, Guatemala, Petén, San Bartolo, mural painting, artistic techniques, painters, artists, Late Preclassic period Like the artist in charge of drawings for the San Bartolo Archaeological Project, the murals of San Bartolo have been documented as faithfully as possible through scale drawings and watercolor paintings. The illustration process presented me with the opportunity to conduct a very detailed observation of both the pictorial technique and the style of the San Bartolo artists. Just like modern artists copy the works of Rembrandt and Michelangelo to get acquainted with their techniques, in the San Bartolo murals every line, color, figure and even paint drops were copied, providing an opportunity to study the Maya masters of the Late Preclassic period. Now, all observations will be presented in regard to the preparation of walls, the design, the composition, the pictorial technique and the style of the San Bartolo murals. PREPARATION OF WALLS Structure Sub-1 in Las Pinturas was conceived and built as a unitary addition to the east side of the mound (Figure 1). The structure was specifically designed to be painted with murals and intended to be easily seen. Las Pinturas Sub-1 is a single, open room with three main doorways in the façade and two secondary ones at the sides. The walls climb until they form a curvature similar to the springing of a vault, but it is known that this room was not vaulted. Instead, the walls continue climbing vertically until they form a frieze that protrudes slightly from the walls and surrounds the four sides of the room, and on which the murals were painted.