Maxwell's Equations Lindsay Guilmette (Class of 2012) Sacred Heart University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

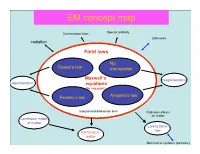

EM Concept Map

EM concept map Conservation laws Special relativity EM waves radiation Field laws No Gauss’s law monopoles ConservationMaxwell’s laws magnetostatics electrostatics equations (In vacuum) Faraday’s law Ampere’s law Integral and differential form Radiation effects on matter Continuum model of matter Lorenz force law EM fields in matter Mechanical systems (particles) Electricity and Magnetism PHYS-350: (updated Sept. 9th, (1605-1725 Monday, Wednesday, Leacock 109) 2010) Instructor: Shaun Lovejoy, Rutherford Physics, rm. 213, local Outline: 6537, email: [email protected]. 1. Vector Analysis: Tutorials: Tuesdays 4:15pm-5:15pm, location: the “Boardroom” Algebra, differential and integral calculus, curvilinear coordinates, (the southwest corner, ground floor of Rutherford physics). Office Hours: Thursday 4-5pm (either Lhermitte or Gervais, see Dirac function, potentials. the schedule on the course site). 2. Electrostatics: Teaching assistant: Julien Lhermitte, rm. 422, local 7033, email: Definitions, basic notions, laws, divergence and curl of the electric [email protected] potential, work and energy. Gervais, Hua Long, ERP-230, [email protected] 3. Special techniques: Math background: Prerequisites: Math 222A,B (Calculus III= Laplace's equation, images, seperation of variables, multipole multivariate calculus), 223A,B (Linear algebra), expansion. Corequisites: 314A (Advanced Calculus = vector 4. Electrostatic fields in matter: calculus), 315A (Ordinary differential equations) Polarization, electric displacement, dielectrics. Primary Course Book: "Introduction to Electrodynamics" by D. 5. Magnetostatics: J. Griffiths, Prentice-Hall, (1999, third edition). Lorenz force law, Biot-Savart law, divergence and curl of B, vector Similar books: potentials. -“Electromagnetism”, G. L. Pollack, D. R. Stump, Addison and 6. Magnetostatic fields in matter: Wesley, 2002. -

James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell JAMES CLERK MAXWELL Perspectives on his Life and Work Edited by raymond flood mark mccartney and andrew whitaker 3 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries c Oxford University Press 2014 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2014 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2013942195 ISBN 978–0–19–966437–5 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Electricity Outline

Electricity Outline A. Electrostatics 1. Charge q is measured in coulombs 2. Three ways to charge something. Charge by: Friction, Conduction and Induction 3. Coulomb’s law for point or spherical charges: q1 q2 2 FE FE FE = kq1q2/r r 9 2 2 where k = 9.0 x 10 Nm /Coul 4. Electric field E = FE/qo (qo is a small, + test charge) F = qE Point or spherically symmetric charge distribution: E = kq/r2 E is constant above or below an ∞, charged sheet. 5. Faraday’s Electric Lines of Force rules: E 1. Lines originate on + and terminate on - _ 2. The E field vector is tangent to the line of force + 3. Electric field strength is proportional to line density 4. Lines are ┴ to conducting surfaces. 5. E = 0 inside a hollow or solid conductor 6. Electric potential difference (voltage): ΔV = W/qo We usually drop the Δ and just write V. Sometimes the voltage provided by a battery is know as the electromotive force (emf) ε 7. Potential Energy due to point charges or spherically symmetric charge distribution V= kQ/r 8. Equipotential surfaces are surfaces with constant voltage. The electric field vector is always to an equipotential surface. 9. Emax Air = 3,000,000 N/coul = 30,000 V/cm. If you exceed this value, you will create a conducting path by ripping e-s off air molecules. B. Capacitors 1. Capacitors A. C = q/V; unit of capacitance is the Farad = coul/volt B. For Parallel plate capacitors: V = E d C is proportional to A/d where A is the area of the plates and d is the plate separation. -

Gauss' Linking Number Revisited

October 18, 2011 9:17 WSPC/S0218-2165 134-JKTR S0218216511009261 Journal of Knot Theory and Its Ramifications Vol. 20, No. 10 (2011) 1325–1343 c World Scientific Publishing Company DOI: 10.1142/S0218216511009261 GAUSS’ LINKING NUMBER REVISITED RENZO L. RICCA∗ Department of Mathematics and Applications, University of Milano-Bicocca, Via Cozzi 53, 20125 Milano, Italy [email protected] BERNARDO NIPOTI Department of Mathematics “F. Casorati”, University of Pavia, Via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy Accepted 6 August 2010 ABSTRACT In this paper we provide a mathematical reconstruction of what might have been Gauss’ own derivation of the linking number of 1833, providing also an alternative, explicit proof of its modern interpretation in terms of degree, signed crossings and inter- section number. The reconstruction presented here is entirely based on an accurate study of Gauss’ own work on terrestrial magnetism. A brief discussion of a possibly indepen- dent derivation made by Maxwell in 1867 completes this reconstruction. Since the linking number interpretations in terms of degree, signed crossings and intersection index play such an important role in modern mathematical physics, we offer a direct proof of their equivalence. Explicit examples of its interpretation in terms of oriented area are also provided. Keywords: Linking number; potential; degree; signed crossings; intersection number; oriented area. Mathematics Subject Classification 2010: 57M25, 57M27, 78A25 1. Introduction The concept of linking number was introduced by Gauss in a brief note on his diary in 1833 (see Sec. 2 below), but no proof was given, neither of its derivation, nor of its topological meaning. Its derivation remained indeed a mystery. -

Advanced Magnetism and Electromagnetism

ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY SERIES ADVANCED MAGNETISM AND ELECTROMAGNETISM i/•. •, / .• ;· ... , -~-> . .... ,•.,'. ·' ,,. • _ , . ,·; . .:~ ~:\ :· ..~: '.· • ' ~. 1. .. • '. ~:;·. · ·!.. ., l• a publication $2 50 ADVANCED MAGNETISM AND ELECTROMAGNETISM Edited by Alexander Schure, Ph.D., Ed. D. - JOHN F. RIDER PUBLISHER, INC., NEW YORK London: CHAPMAN & HALL, LTD. Copyright December, 1959 by JOHN F. RIDER PUBLISHER, INC. All rights reserved. This book or parts thereof may not be reproduced in any form or in any language without permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 59-15913 Printed in the United States of America PREFACE The concepts of magnetism and electromagnetism form such an essential part of the study of electronic theory that the serious student of this field must have a complete understanding of these principles. The considerations relating to magnetic theory touch almost every aspect of electronic development. This book is the second of a two-volume treatment of the subject and continues the attention given to the major theoretical con siderations of magnetism, magnetic circuits and electromagnetism presented in the first volume of the series.• The mathematical techniques used in this volume remain rela tively simple but are sufficiently detailed and numerous to permit the interested student or technician extensive experience in typical computations. Greater weight is given to problem solutions. To ensure further a relatively complete coverage of the subject matter, attention is given to the presentation of sufficient information to outline the broad concepts adequately. Rather than attempting to cover a large body of less important material, the selected major topics are treated thoroughly. Attention is given to the typical practical situations and problems which relate to the subject matter being presented, so as to afford the reader an understanding of the applications of the principles he has learned. -

The Concept of Field in the History of Electromagnetism

The concept of field in the history of electromagnetism Giovanni Miano Department of Electrical Engineering University of Naples Federico II ET2011-XXVII Riunione Annuale dei Ricercatori di Elettrotecnica Bologna 16-17 giugno 2011 Celebration of the 150th Birthday of Maxwell’s Equations 150 years ago (on March 1861) a young Maxwell (30 years old) published the first part of the paper On physical lines of force in which he wrote down the equations that, by bringing together the physics of electricity and magnetism, laid the foundations for electromagnetism and modern physics. Statue of Maxwell with its dog Toby. Plaque on E-side of the statue. Edinburgh, George Street. Talk Outline ! A brief survey of the birth of the electromagnetism: a long and intriguing story ! A rapid comparison of Weber’s electrodynamics and Maxwell’s theory: “direct action at distance” and “field theory” General References E. T. Wittaker, Theories of Aether and Electricity, Longam, Green and Co., London, 1910. O. Darrigol, Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einste in, Oxford University Press, 2000. O. M. Bucci, The Genesis of Maxwell’s Equations, in “History of Wireless”, T. K. Sarkar et al. Eds., Wiley-Interscience, 2006. Magnetism and Electricity In 1600 Gilbert published the “De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure” (On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on That Great Magnet the Earth). ! The Earth is magnetic ()*+(,-.*, Magnesia ad Sipylum) and this is why a compass points north. ! In a quite large class of bodies (glass, sulphur, …) the friction induces the same effect observed in the amber (!"#$%&'(, Elektron). Gilbert gave to it the name “electricus”. -

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1. A. Pre-1820. (1) Electrostatics (frictional electricity) • 1780s. Coulomb's description: ! Two electric fluids: positive and negative. ! Inverse square law: It follows therefore from these three tests, that the repulsive force that the two balls -- [which were] electrified with the same kind of electricity -- exert on each other, Charles-Augustin de Coulomb follows the inverse proportion of (1736-1806) the square of the distance."" (2) Magnetism: Coulomb's description: • Two fluids ("astral" and "boreal") obeying inverse square law. • No magnetic monopoles: fluids are imprisoned in molecules of magnetic bodies. (3) Galvanism • 1770s. Galvani's frog legs. "Animal electricity": phenomenon belongs to biology. • 1800. Volta's ("volatic") pile. Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) • Pile consists of alternating copper and • Charged rod connected zinc plates separated by to inner foil. brine-soaked cloth. • Outer foil grounded. • A "battery" of Leyden • Inner and outer jars that can surfaces store equal spontaeously recharge but opposite charges. themselves. 1745 Leyden jar. • Volta: Pile is an electric phenomenon and belongs to physics. • But: Nicholson and Carlisle use voltaic current to decompose Alessandro Volta water into hydrogen and oxygen. Pile belongs to chemistry! (1745-1827) • Are electricity and magnetism different phenomena? ! Electricity involves violent actions and effects: sparks, thunder, etc. ! Magnetism is more quiet... Hans Christian • 1820. Oersted's Experimenta circa effectum conflictus elecrici in Oersted (1777-1851) acum magneticam ("Experiments on the effect of an electric conflict on the magnetic needle"). ! Galvanic current = an "electric conflict" between decompositions and recompositions of positive and negative electricities. ! Experiments with a galvanic source, connecting wire, and rotating magnetic needle: Needle moves in presence of pile! "Otherwise one could not understand how Oersted's Claims the same portion of the wire drives the • Electric conflict acts on magnetic poles. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

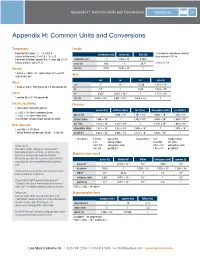

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215 Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Temperature Length Fahrenheit to Celsius: °C = (°F-32)/1.8 1 micrometer (sometimes referred centimeter (cm) meter (m) inch (in) Celsius to Fahrenheit: °F = (1.8 × °C) + 32 to as micron) = 10-6 m Fahrenheit to Kelvin: convert °F to °C, then add 273.15 centimeter (cm) 1 1.000 × 10–2 0.3937 -3 Celsius to Kelvin: add 273.15 meter (m) 100 1 39.37 1 mil = 10 in Volume inch (in) 2.540 2.540 × 10–2 1 –3 3 1 liter (l) = 1.000 × 10 cubic meters (m ) = 61.02 Area cubic inches (in3) cm2 m2 in2 circ mil Mass cm2 1 10–4 0.1550 1.974 × 105 1 kilogram (kg) = 1000 grams (g) = 2.205 pounds (lb) m2 104 1 1550 1.974 × 109 Force in2 6.452 6.452 × 10–4 1 1.273 × 106 1 newton (N) = 0.2248 pounds (lb) circ mil 5.067 × 10–6 5.067 × 10–10 7.854 × 10–7 1 Electric resistivity Pressure 1 micro-ohm-centimeter (µΩ·cm) pascal (Pa) millibar (mbar) torr (Torr) atmosphere (atm) psi (lbf/in2) = 1.000 × 10–6 ohm-centimeter (Ω·cm) –2 –3 –6 –4 = 1.000 × 10–8 ohm-meter (Ω·m) pascal (Pa) 1 1.000 × 10 7.501 × 10 9.868 × 10 1.450 × 10 = 6.015 ohm-circular mil per foot (Ω·circ mil/ft) millibar (mbar) 1.000 × 102 1 7.502 × 10–1 9.868 × 10–4 1.450 × 10–2 2 0 –3 –2 Heat flow rate torr (Torr) 1.333 × 10 1.333 × 10 1 1.316 × 10 1.934 × 10 5 3 2 1 1 watt (W) = 3.413 Btu/h atmosphere (atm) 1.013 × 10 1.013 × 10 7.600 × 10 1 1.470 × 10 1 British thermal unit per hour (Btu/h) = 0.2930 W psi (lbf/in2) 6.897 × 103 6.895 × 101 5.172 × 101 6.850 × 10–2 1 1 torr (Torr) = 133.332 pascal (Pa) 1 pascal (Pa) = 0.01 millibar (mbar) 1.33 millibar (mbar) 0.007501 torr (Torr) –6 A Note on SI 0.001316 atmosphere (atm) 9.87 × 10 atmosphere (atm) 2 –4 2 The values in this catalog are expressed in 0.01934 psi (lbf/in ) 1.45 × 10 psi (lbf/in ) International System of Units, or SI (from the Magnetic induction B French Le Système International d’Unités). -

Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1970 Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System Herman G. Hamre Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Hamre, Herman G., "Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System" (1970). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3780. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/3780 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUTOMATIC IRRIGATION: SENSORS AND SYSTEM BY HERMAN G. HAMRE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science, Major in Electrical Engineering, South Dakota State University 1970 SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY AUTOMATIC IRRIGATION: SENSORS AND SYSTEM This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investi gation by a candidate for the degree, Master of Science, and is accept able as meeting the thesis requirements for this degree, but without implying that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. �--- -"""'" _ _ -���--- - _ _ _ _____ -A>� - 7 7 T b � s/./ifjvisor ate Head, Electrical -r-oate Engineering Department ACKNOWLE GEMENTS The author wishes to express his sincere appreciation to Dr. A. J. Kurtenbach for his patient guidance and helpful suggestions, and to the Water Resources Institute for their support of this research. -

Electricity and Magnetism

Lecture 10 Fundamentals of Physics Phys 120, Fall 2015 Electricity and Magnetism A. J. Wagner North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58102 Fargo, September 24, 2015 Overview • Unexplained phenomena • Charges and electric forces revealed • Currents and circuits • Electricity and Magnetism are related! 1 Newton’s dream I wish we could derive the rest of the phenomena of Nature by the same kind of reasoning from mechanical principles, for I am induced by many reasons to suspect that they may all depend upon certain forces by which the particles of bodies, by some cause hitherto unknown, are either mutually impelled towards one another, and cohere in regular figures, or are repelled and recede from one another. from the preface of Newton’s Principia 2 What were those mysterious phenomena? 900 BC: Magnus, a Greek shepherd, walks across a field of black stones which pull the iron nails out of his sandals and the iron tip from his shepherd’s staff (authenticity not guaranteed). This region becomes known as Magnesia. 600 BC: Thales of Miletos(Greece) discovered that by rubbing an ’elektron’ (a hard, fossilized resin that today is known as amber) against a fur cloth, it would attract particles of straw and feathers. This strange effect remained a mystery for over 2000 years. 1269 AD: Petrus Peregrinus of Picardy, Italy, discovers that natural spherical magnets (lodestones) align needles with lines of longitude pointing between two pole positions on the stone. 3 ca. 1600: Dr.William Gilbert (court physician to Queen Elizabeth) discovers that the earth is a giant magnet just like one of the stones of Peregrinus, explaining how compasses work. -

Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 151. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/151 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 30 Magnetic Fields of Currents 30-1 Magnetic Field around an Electric Current The first evidence for the existence of a magnetic field around an electric current was observed in 1820 by Hans Christian Oersted (1777-1851). He found that a wire carrying current caused a freely pivoted compass needle B D N rDirection I of current D II. • ~ I I In wire ' \ N I I c , I s c (a) (b) Fig. 30-1 Oersted's experiment. Compass needle is deflected toward the west when the wire CD carrying current is placed above it and the direction of the current is toward the north, from C to D. in its vicinity to be deflected. If the current in a long straight wire is directed from C to D, as shown in Figure 30-1, a compass needle below it, whose initial orientation is shown in dotted lines, will have its north pole deflected to the left and its south pole deflected to the right.