H. C. Ørsted and the Discovery of Electromagnetism During a Lecture Given in the Spring of 1820 Hans Christian Ørsted De- Cided to Perform an Experiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optical Timeline by Tony Oursler

Optical Timeline by Tony Oursler 1 Iris is thought to be derived from the RED Symyaz leads the fallen angels. Archimedes (c. 287212 b.c.) is said to Greek word for speaker or messenger. According to Enoch, they came to earth have used a large magnifying lens or Seth, the Egyptian god most associated of their own free will at Mount Hermon, burning-glass, which focused the suns Fifth century b.c. Chinese philosopher with evil, is depicted in many guises: descending like stars. This description rays, to set fire to Roman ships off Mo Ti, in the first description of the gives rise to the name Lucifer, “giver of Syracuse. camera obscura, refers to the pinhole as a black pig, a tall, double-headed figure light.” “collection place” and “locked treasure with a snout, and a serpent. Sometimes And now there is no longer any “I have seen Satan fall like lightning room.” he is black, a positive color for the difficulty in understanding the images in from heaven.” (Luke 10:1820) Egyptians, symbolic of the deep tones of mirrors and in all smooth and bright Platos Cave depicts the dilemma of fertile river deposits; at other times he is surfaces. The fires from within and from the uneducated in a graphic tableau of red, a negative color reflected by the without communicate about the smooth light and shadow. The shackled masses parched sands that encroach upon the surface, and from one image which is are kept in shadow, unable to move crops. Jeffrey Burton Russell suggests variously refracted. -

EM Concept Map

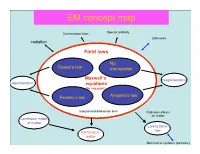

EM concept map Conservation laws Special relativity EM waves radiation Field laws No Gauss’s law monopoles ConservationMaxwell’s laws magnetostatics electrostatics equations (In vacuum) Faraday’s law Ampere’s law Integral and differential form Radiation effects on matter Continuum model of matter Lorenz force law EM fields in matter Mechanical systems (particles) Electricity and Magnetism PHYS-350: (updated Sept. 9th, (1605-1725 Monday, Wednesday, Leacock 109) 2010) Instructor: Shaun Lovejoy, Rutherford Physics, rm. 213, local Outline: 6537, email: [email protected]. 1. Vector Analysis: Tutorials: Tuesdays 4:15pm-5:15pm, location: the “Boardroom” Algebra, differential and integral calculus, curvilinear coordinates, (the southwest corner, ground floor of Rutherford physics). Office Hours: Thursday 4-5pm (either Lhermitte or Gervais, see Dirac function, potentials. the schedule on the course site). 2. Electrostatics: Teaching assistant: Julien Lhermitte, rm. 422, local 7033, email: Definitions, basic notions, laws, divergence and curl of the electric [email protected] potential, work and energy. Gervais, Hua Long, ERP-230, [email protected] 3. Special techniques: Math background: Prerequisites: Math 222A,B (Calculus III= Laplace's equation, images, seperation of variables, multipole multivariate calculus), 223A,B (Linear algebra), expansion. Corequisites: 314A (Advanced Calculus = vector 4. Electrostatic fields in matter: calculus), 315A (Ordinary differential equations) Polarization, electric displacement, dielectrics. Primary Course Book: "Introduction to Electrodynamics" by D. 5. Magnetostatics: J. Griffiths, Prentice-Hall, (1999, third edition). Lorenz force law, Biot-Savart law, divergence and curl of B, vector Similar books: potentials. -“Electromagnetism”, G. L. Pollack, D. R. Stump, Addison and 6. Magnetostatic fields in matter: Wesley, 2002. -

Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary Journal Item How to cite: Stenhouse, Brigitte (2020). Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary. The Mathematical Intelligencer (Early Access). For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2020 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1007/s00283-020-09998-6 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary BRIGITTE STENHOUSE ary Somerville’s life as a mathematician and mathematician). Although no scientific learned society had a savant in nineteenth-century Great Britain was formal statute barring women during Somerville’s lifetime, MM heavily influenced by her gender; as a woman, there was nonetheless a great reluctance even toallow women her access to the ideas and resources developed and into the buildings, never mind to endow them with the rights circulated in universities and scientific societies was highly of members. Except for the visit of the prolific author Margaret restricted. However, her engagement with learned institu- Cavendish in 1667, the Royal Society of London did not invite tions was by no means nonexistent, and although she was women into their hallowed halls until 1876, with the com- 90 before being elected a full member of any society mencement of their second conversazione [15, 163], which (Societa` Geografica Italiana, 1870), Somerville (Figure 1) women were permitted to attend.1 As late as 1886, on the nevertheless benefited from the resources and social nomination of Isis Pogson as a fellow, the Council of the Royal networks cultivated by such institutions from as early as Astronomical Society chose to interpret their constitution as 1812. -

Printer Tech Tips—Cause & Effects of Static Electricity in Paper

Printer Tech Tips Cause & Effects of Static Electricity in Paper Problem The paper has developed a static electrical charge causing an abnormal sheet-to- sheet or sheet-to-material attraction which is difficult to separate. This condition may result in feeder trip-offs, print voids from surface contamination, ink offset, Sappi Printer Technical Service or poor sheet jog in the delivery. 877 SappiHelp (727 7443) Description Static electricity is defined as a non-moving, non-flowing electrical charge or in simple terms, electricity at rest. Static electricity becomes visible and dynamic during the brief moment it sparks a discharge and for that instant it’s no longer at rest. Lightning is the result of static discharge as is the shock you receive just before contacting a grounded object during unusually dry weather. Matter is composed of atoms, which in turn are composed of protons, neutrons, and electrons. The number of protons and neutrons, which make up the atoms nucleus, determine the type of material. Electrons orbit the nucleus and balance the electrical charge of the protons. When both negative and positive are equal, the charge of the balanced atom is neutral. If electrons are removed or added to this configuration, the overall charge becomes either negative or positive resulting in an unbalanced atom. Materials with high conductivity, such as steel, are called conductors and maintain neutrality because their electrons can move freely from atom to atom to balance any applied charges. Therefore, conductors can dissipate static when properly grounded. Non-conductive materials, or insulators such as plastic and wood, have the opposite property as their electrons can not move freely to maintain balance. -

Magnetic Fields Magnetism Magnetic Field

PHY2061 Enriched Physics 2 Lecture Notes Magnetic Fields Magnetic Fields Disclaimer: These lecture notes are not meant to replace the course textbook. The content may be incomplete. Some topics may be unclear. These notes are only meant to be a study aid and a supplement to your own notes. Please report any inaccuracies to the professor. Magnetism Is ubiquitous in every-day life! • Refrigerator magnets (who could live without them?) • Coils that deflect the electron beam in a CRT television or monitor • Cassette tape storage (audio or digital) • Computer disk drive storage • Electromagnet for Magnetic Resonant Imaging (MRI) Magnetic Field Magnets contain two poles: “north” and “south”. The force between like-poles repels (north-north, south-south), while opposite poles attract (north-south). This is reminiscent of the electric force between two charged objects (which can have positive or negative charge). Recall that the electric field was invoked to explain the “action at a distance” effect of the electric force, and was defined by: F E = qel where qel is electric charge of a positive test charge and F is the force acting on it. We might be tempted to define the same for the magnetic field, and write: F B = qmag where qmag is the “magnetic charge” of a positive test charge and F is the force acting on it. However, such a single magnetic charge, a “magnetic monopole,” has never been observed experimentally! You cannot break a bar magnet in half to get just a north pole or a south pole. As far as we know, no such single magnetic charges exist in the universe, D. -

Humphry Davy: Science, Authorship, and the Changing Romantic

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2010-11-29 Humphry Davy: Science, Authorship, and the Changing Romantic Marianne Lind Baker Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Baker, Marianne Lind, "Humphry Davy: Science, Authorship, and the Changing Romantic" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 2647. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2647 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Page Humphry Davy: Science, Authorship, and the Changing ―Romantic I‖ Marianne Lind Baker A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Nicholas Mason, Chair Leslee Thorne-Murphy Paul Westover Department of English Brigham Young University December 2010 Copyright © 2010 Marianne Baker All Rights Reserved Abstract ABSTRACT Humphry Davy: Science, Authorship, and the Changing ―Romantic I‖ Marianne Lind Baker Department of English Master of Arts In the mid to late 1700s, men of letters became more and more interested in the natural world. From studies in astronomy to biology, chemistry, and medicine, these ―philosophers‖ pioneered what would become our current scientific categories. While the significance of their contributions to these fields has been widely appreciated historically, the interconnection between these men and their literary counterparts has not. A study of the ―Romantic man of science‖ reveals how much that figure has in common with the traditional ―Romantic‖ literary figure embodied by poets like William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. -

Scientists on Currencies

“For making the world a wealthier place” TOP 10 ___________________________________________________________________________________ SCIENTISTS ON BANKNOTES 1. Isaac Newton 2. Charles Darwin 3. Michael Faraday 4. Copernicus 5. Galileo 6. Marie Curie 7. Leonardo da Vinci 8. Albert Einstein 9. Hideyo Noguchi 10. Nikola Tesla Will Philip Emeagwali be on the Nigerian Money? “Put Philip Emeagwali on Nigeria’s Currency,” Central Bank of Nigeria official pleads. See Details Below Physicist Albert Einstein is honored on Israeli five pound currency. Galileo Gallilei on the Italian 2000 Lire. Isaac Newton honored on the British pound. Bacteriologist Hideyo Noguchi honored on the Japanese banknote. The image of Carl Friedrich Gauss on Germany's 10- mark banknote inspired young Germans to become mathematicians. Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519), the Italian polymath, is honored on their banknote. Maria Sklodowska–Curie is honoured on the Polish banknote. Carl Linnaeus is honored on the Swedish banknote (100 Swedish Krona) Nikola Tesla is honored on Serbia’s banknote. Note actual equation on banknote (Serbia’s 100-dinar note) Honorable Mentions Developing Story Banker Wanted Emeagwali on Nigerian Currency In early 2000s, the Central Bank of Nigeria announced that new banknotes will be commissioned. An economist of the Central Bank of Nigeria commented: “In Europe, heroes of science are portrayed on banknotes. In Africa, former heads of state are portrayed on banknotes. Why is that so?” His logic was that the Central Bank of Nigeria should end its era of putting only Nigerian political leaders on the money. In Africa, only politicians were permitted by politicians to be on the money. Perhaps, you’ve heard of the one-of-a-kind debate to put Philip Emeagwali on the Nigerian money. -

Gauss' Linking Number Revisited

October 18, 2011 9:17 WSPC/S0218-2165 134-JKTR S0218216511009261 Journal of Knot Theory and Its Ramifications Vol. 20, No. 10 (2011) 1325–1343 c World Scientific Publishing Company DOI: 10.1142/S0218216511009261 GAUSS’ LINKING NUMBER REVISITED RENZO L. RICCA∗ Department of Mathematics and Applications, University of Milano-Bicocca, Via Cozzi 53, 20125 Milano, Italy [email protected] BERNARDO NIPOTI Department of Mathematics “F. Casorati”, University of Pavia, Via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy Accepted 6 August 2010 ABSTRACT In this paper we provide a mathematical reconstruction of what might have been Gauss’ own derivation of the linking number of 1833, providing also an alternative, explicit proof of its modern interpretation in terms of degree, signed crossings and inter- section number. The reconstruction presented here is entirely based on an accurate study of Gauss’ own work on terrestrial magnetism. A brief discussion of a possibly indepen- dent derivation made by Maxwell in 1867 completes this reconstruction. Since the linking number interpretations in terms of degree, signed crossings and intersection index play such an important role in modern mathematical physics, we offer a direct proof of their equivalence. Explicit examples of its interpretation in terms of oriented area are also provided. Keywords: Linking number; potential; degree; signed crossings; intersection number; oriented area. Mathematics Subject Classification 2010: 57M25, 57M27, 78A25 1. Introduction The concept of linking number was introduced by Gauss in a brief note on his diary in 1833 (see Sec. 2 below), but no proof was given, neither of its derivation, nor of its topological meaning. Its derivation remained indeed a mystery. -

Alessandro Volta and the Discovery of the Battery

1 Primary Source 12.2 VOLTA AND THE DISCOVERY OF THE BATTERY1 Alessandro Volta (1745–1827) was born in the Duchy of Milan in a town called Como. He was raised as a Catholic and remained so throughout his life. Volta became a professor of physics in Como, and soon took a significant interest in electricity. First, he began to work with the chemistry of gases, during which he discovered methane gas. He then studied electrical capacitance, as well as derived new ways of studying both electrical potential and charge. Most famously, Volta discovered what he termed a Voltaic pile, which was the first electrical battery that could continuously provide electrical current to a circuit. Needless to say, Volta’s discovery had a major impact in science and technology. In light of his contribution to the study of electrical capacitance and discovery of the battery, the electrical potential difference, voltage, and the unit of electric potential, the volt, were named in honor of him. The following passage is excerpted from an essay, written in French, “On the Electricity Excited by the Mere Contact of Conducting Substances of Different Kinds,” which Volta sent in 1800 to the President of the Royal Society in London, Joseph Banks, in hope of its publication. The essay, described how to construct a battery, a source of steady electrical current, which paved the way toward the “electric age.” At this time, Volta was working as a professor at the University of Pavia. For the excerpt online, click here. The chief of these results, and which comprehends nearly all the others, is the construction of an apparatus which resembles in its effects viz. -

Chapter 7 Magnetism and Electromagnetism

Chapter 7 Magnetism and Electromagnetism Objectives • Explain the principles of the magnetic field • Explain the principles of electromagnetism • Describe the principle of operation for several types of electromagnetic devices • Explain magnetic hysteresis • Discuss the principle of electromagnetic induction • Describe some applications of electromagnetic induction 1 The Magnetic Field • A permanent magnet has a magnetic field surrounding it • A magnetic field is envisioned to consist of lines of force that radiate from the north pole to the south pole and back to the north pole through the magnetic material Attraction and Repulsion • Unlike magnetic poles have an attractive force between them • Two like poles repel each other 2 Altering a Magnetic Field • When nonmagnetic materials such as paper, glass, wood or plastic are placed in a magnetic field, the lines of force are unaltered • When a magnetic material such as iron is placed in a magnetic field, the lines of force tend to be altered to pass through the magnetic material Magnetic Flux • The force lines going from the north pole to the south pole of a magnet are called magnetic flux (φ); units: weber (Wb) •The magnetic flux density (B) is the amount of flux per unit area perpendicular to the magnetic field; units: tesla (T) 3 Magnetizing Materials • Ferromagnetic materials such as iron, nickel and cobalt have randomly oriented magnetic domains, which become aligned when placed in a magnetic field, thus they effectively become magnets Electromagnetism • Electromagnetism is the production -

Chapter 22 Magnetism

Chapter 22 Magnetism 22.1 The Magnetic Field 22.2 The Magnetic Force on Moving Charges 22.3 The Motion of Charged particles in a Magnetic Field 22.4 The Magnetic Force Exerted on a Current- Carrying Wire 22.5 Loops of Current and Magnetic Torque 22.6 Electric Current, Magnetic Fields, and Ampere’s Law Magnetism – Is this a new force? Bar magnets (compass needle) align themselves in a north-south direction. Poles: Unlike poles attract, like poles repel Magnet has NO effect on an electroscope and is not influenced by gravity Magnets attract only some objects (iron, nickel etc) No magnets ever repel non magnets Magnets have no effect on things like copper or brass Cut a bar magnet-you get two smaller magnets (no magnetic monopoles) Earth is like a huge bar magnet Figure 22–1 The force between two bar magnets (a) Opposite poles attract each other. (b) The force between like poles is repulsive. Figure 22–2 Magnets always have two poles When a bar magnet is broken in half two new poles appear. Each half has both a north pole and a south pole, just like any other bar magnet. Figure 22–4 Magnetic field lines for a bar magnet The field lines are closely spaced near the poles, where the magnetic field B is most intense. In addition, the lines form closed loops that leave at the north pole of the magnet and enter at the south pole. Magnetic Field Lines If a compass is placed in a magnetic field the needle lines up with the field. -

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1. A. Pre-1820. (1) Electrostatics (frictional electricity) • 1780s. Coulomb's description: ! Two electric fluids: positive and negative. ! Inverse square law: It follows therefore from these three tests, that the repulsive force that the two balls -- [which were] electrified with the same kind of electricity -- exert on each other, Charles-Augustin de Coulomb follows the inverse proportion of (1736-1806) the square of the distance."" (2) Magnetism: Coulomb's description: • Two fluids ("astral" and "boreal") obeying inverse square law. • No magnetic monopoles: fluids are imprisoned in molecules of magnetic bodies. (3) Galvanism • 1770s. Galvani's frog legs. "Animal electricity": phenomenon belongs to biology. • 1800. Volta's ("volatic") pile. Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) • Pile consists of alternating copper and • Charged rod connected zinc plates separated by to inner foil. brine-soaked cloth. • Outer foil grounded. • A "battery" of Leyden • Inner and outer jars that can surfaces store equal spontaeously recharge but opposite charges. themselves. 1745 Leyden jar. • Volta: Pile is an electric phenomenon and belongs to physics. • But: Nicholson and Carlisle use voltaic current to decompose Alessandro Volta water into hydrogen and oxygen. Pile belongs to chemistry! (1745-1827) • Are electricity and magnetism different phenomena? ! Electricity involves violent actions and effects: sparks, thunder, etc. ! Magnetism is more quiet... Hans Christian • 1820. Oersted's Experimenta circa effectum conflictus elecrici in Oersted (1777-1851) acum magneticam ("Experiments on the effect of an electric conflict on the magnetic needle"). ! Galvanic current = an "electric conflict" between decompositions and recompositions of positive and negative electricities. ! Experiments with a galvanic source, connecting wire, and rotating magnetic needle: Needle moves in presence of pile! "Otherwise one could not understand how Oersted's Claims the same portion of the wire drives the • Electric conflict acts on magnetic poles.