Humphry Davy: Science, Authorship, and the Changing Romantic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optical Timeline by Tony Oursler

Optical Timeline by Tony Oursler 1 Iris is thought to be derived from the RED Symyaz leads the fallen angels. Archimedes (c. 287212 b.c.) is said to Greek word for speaker or messenger. According to Enoch, they came to earth have used a large magnifying lens or Seth, the Egyptian god most associated of their own free will at Mount Hermon, burning-glass, which focused the suns Fifth century b.c. Chinese philosopher with evil, is depicted in many guises: descending like stars. This description rays, to set fire to Roman ships off Mo Ti, in the first description of the gives rise to the name Lucifer, “giver of Syracuse. camera obscura, refers to the pinhole as a black pig, a tall, double-headed figure light.” “collection place” and “locked treasure with a snout, and a serpent. Sometimes And now there is no longer any “I have seen Satan fall like lightning room.” he is black, a positive color for the difficulty in understanding the images in from heaven.” (Luke 10:1820) Egyptians, symbolic of the deep tones of mirrors and in all smooth and bright Platos Cave depicts the dilemma of fertile river deposits; at other times he is surfaces. The fires from within and from the uneducated in a graphic tableau of red, a negative color reflected by the without communicate about the smooth light and shadow. The shackled masses parched sands that encroach upon the surface, and from one image which is are kept in shadow, unable to move crops. Jeffrey Burton Russell suggests variously refracted. -

Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary Journal Item How to cite: Stenhouse, Brigitte (2020). Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary. The Mathematical Intelligencer (Early Access). For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2020 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1007/s00283-020-09998-6 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary BRIGITTE STENHOUSE ary Somerville’s life as a mathematician and mathematician). Although no scientific learned society had a savant in nineteenth-century Great Britain was formal statute barring women during Somerville’s lifetime, MM heavily influenced by her gender; as a woman, there was nonetheless a great reluctance even toallow women her access to the ideas and resources developed and into the buildings, never mind to endow them with the rights circulated in universities and scientific societies was highly of members. Except for the visit of the prolific author Margaret restricted. However, her engagement with learned institu- Cavendish in 1667, the Royal Society of London did not invite tions was by no means nonexistent, and although she was women into their hallowed halls until 1876, with the com- 90 before being elected a full member of any society mencement of their second conversazione [15, 163], which (Societa` Geografica Italiana, 1870), Somerville (Figure 1) women were permitted to attend.1 As late as 1886, on the nevertheless benefited from the resources and social nomination of Isis Pogson as a fellow, the Council of the Royal networks cultivated by such institutions from as early as Astronomical Society chose to interpret their constitution as 1812. -

H. C. Ørsted and the Discovery of Electromagnetism During a Lecture Given in the Spring of 1820 Hans Christian Ørsted De- Cided to Perform an Experiment

H. C. Ørsted and the Discovery of Electromagnetism During a lecture given in the spring of 1820 Hans Christian Ørsted de- cided to perform an experiment. As he described it years later, \The plan of the first experiment was, to make the current of a little galvanic trough apparatus, commonly used in his lectures, pass through a very thin platina wire, which was placed over a compass covered with glass. The preparations for the experiments were made, but some accident having hindered him from trying it before the lec- ture, he intended to defer it to another opportunity; yet during the lecture, the probability of its success appeared stronger, so that he made the first experiment in the presence of the audience. The mag- netical needle, though included in a box, was disturbed; but as the effect was very feeble, and must, before its law was discovered, seem very irregular, the experiment made no strong impression on the au- dience. It may appear strange, that the discoverer made no further experiments upon the subject during three months; he himself finds it difficult enough to conceive it; but the extreme feebleness and seeming confusion of the phenomena in the first experiment, the remembrance of the numerous errors committed upon this subject by earlier philoso- phers, and particularly by his friend Ritter, the claim such a matter has to be treated with earnest attention, may have determined him to delay his researches to a more convenient time. In the month of July 1820, he again resumed the experiment, making use of a much more considerable galvanical apparatus."1 The effect that Ørsted observed may have been \very feeble". -

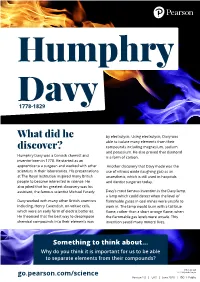

What Did He Discover?

Humphry Davy 1778-1829 What did he by electrolysis. Using electrolysis, Davy was able to isolate many elements from their discover? compounds including magnesium, sodium and potassium. He also proved that diamond Humphry Davy was a Cornish chemist and is a form of carbon. inventor born in 1778. He started as an apprentice to a surgeon and worked with other Another discovery that Davy made was the scientists in their laboratories. His presentations use of nitrous oxide (laughing gas) as an at The Royal Institution inspired many British anaesthetic, which is still used in hospitals people to become interested in science. He and dentist surgeries today. also joked that his greatest discovery was his assistant, the famous scientist Michael Farady. Davy’s most famous invention is the Davy lamp, a lamp which could detect when the level of Davy worked with many other British scientists flammable gases in coal mines were unsafe to including, Henry Cavendish, on voltaic cells, work in. The lamp would burn with a tall blue which were an early form of electric batteries. flame, rather than a short orange flame, when He theorised that the best way to decompose the flammable gas levels were unsafe. This chemical compounds into their elements was invention saved many miners’ lives. Something to think about... Why do you think it is important for us to be able to separate elements from their compounds? PEUK A1929 go.pearson.com/science ©123rf/Jakub Gojda Version 1.0 | UKS | Jan 2020 | DCL1: Public Version 1.0 | UKS | June 2020 | DCL1:PEUK Public A1479 © Teodoro Ortiz Tarrascusa. -

Contributions of Maxwell to Electromagnetism

GENERAL I ARTICLE Contributions of Maxwell to Electromagnetism P V Panat Maxwell, one of the greatest physicists of the nineteenth century, was the founder ofa consistent theory ofelectromag netism. However, it must be noted that significant discov eries and intelligent efforts of Coulomb, Volta, Ampere, Oersted, Faraday, Gauss, Poisson, Helmholtz and others preceded the work of Maxwell, enhancing a partial under P V Panat is Professor of standing of the connection between electricity and magne Physics at the Pune tism. Maxwell, by sheer logic and physical understanding University, His main of the earlier discoveries completed the unification of elec research interests are tricity and magnetism. The aim of this article is to describe condensed matter theory and quantum optics. Maxwell's contribution to electricity and magnetism. Introduction Historically, the phenomenon of magnetism was known at least around the 11th century. Electrical charges were discovered in the mid 17th century. Since then, for a long time, these phenom ena were studied separately since no connection between them could be seen except by analogies. It was Oersted's discovery, in July 1820, that a voltaic current-carrying wire produces a mag netic field, which connected electricity and magnetism. An other significant step towards establishing this connection was taken by Faraday in 1831 by discovering the law of induction. Besides, Faraday was perhaps the first proponent of, what we call in modern language, field. His ideas of the 'lines of force' and the 'tube of force' are akin to the modern idea of a field and flux, respectively. Maxwell was backed by the efforts of these and other pioneers. -

Visions of Volcanoes David M

Visions of Volcanoes David M. Pyle Introduction Since antiquity, volcanoes have been associated with fire, heat, and sulphur, or linked to fiery places — the burning hearth, the blacksmith’s forge, or the underworld. Travellers returned from distant shores with tales of burning mountains, and the epithet stuck. In his dictionary of 1799, Samuel Johnson defined a volcano as ‘a burning mountain that emits flames, stones, &c’, and fire as ‘that which has the power of burning, flame, light, lustre’.1 ‘Fire mountains’ are found around the world, from Fogo (the Azores and Cape Verde Islands) to Fuego (Guatemala, Mexico, and the Canary Islands) and Gunung Api (multiple volcanoes in Indonesia). Similar analogies with fire pervade the technical language of volcanology. Rocks associated with volcanoes are igneous rocks; the fragmental deposits of past volcanic eruptions are pyroclastic rocks; the dark gravel-sized fragments ejected during eruptions are often called cinders, and the finest grain sizes of ejecta are called ash. Specific styles of volcanic activity likewise attract fiery names: from the ‘fire fountains’ that light up the most vigorous eruptions of Kilauea, on Hawaii, to the nuées ardentes that laid waste to the town of St Pierre in Martinique in 1902. However, as became clear to nineteenth-century observers, the action of eruption is not usually associated with combustion: the materials ejected from volcanoes are not usually burning, but glow red or orange because they are hot, and it is this radiant heat that provides the illumination during eruptions. The nineteenth century marked an important transition in the under- standing of the nature of combustion and fire, and of volcanoes and the interior of the earth.2 The early part of the century was also a period when 1 Samuel Johnson, Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language, in Miniature, 11th edn (London: Longman and Rees, 1799), pp. -

Philosophy and the Chemical Revolution After Kant

This material has been published in The Cambridge Companion to German Idealism edited by K.Ameriks. This version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Michela Massimi Philosophy and the Chemical Revolution after Kant Michela Massimi 1. Introduction The term Naturphilosophie denotes a philosophical movement that developed in post- Kantian Germany at the end of the eighteenth century. Fichte and Schelling belonged to this intellectual movement, which had strong cultural links both with Romanticism (including Goethe, Novalis, and Hölderlin) and post-Kantian Idealism. As with any hybrid and transient cultural movement, it is difficult to define Naturphilosophie in terms of a specific manifesto or well-defined cultural program. The term came to denote a fairly broad range of philosophical ideas, whose seeds can be traced back, in various ways, to Kant’s philosophy of nature. Yet, Naturphilosophen gave a completely new twist to Kant’s philosophy of nature, a twist that eventually paved the way to Idealism. The secondary literature on Naturphilosophie has emphasized the role that the movement played for the exact sciences of the early nineteenth century. In a seminal paper (1959/1977, 66-104) on the discovery of energy conservation Thomas Kuhn gave Naturphilosophie(and, in particular, F. W. J. Schelling, credit for stressing the philosophical importance of conversion and transformation processes. These ideas played an important role in the nineteenth-century discovery (carried out independently by Mayer, Joule, and Helmholtz) of the interconvertibility of thermal energy into mechanical work, as well of electricity into magnetism (by Ørsted and Faraday). -

Contents List Somerville

ON THE CONNECTION OF THE PHYSICAL SCIENCES BY MARY SOMERVILLE Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ..………………...1 Section I. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………. …………………..4 Attraction of a Sphere Form of Celestial Bodies Terrestrial Gravitation retains the Moon in her Orbit The Heavenly Bodies move in Conic Sections Gravitation proportional to Mass Gravitation of the Particles of Matter Figure of the Planets How it affects the Motions of their Satellites Rotation and Translation impressed by the same Impulse Motion of the Sun and Solar System Section II. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… …………..………8 Elliptical Motion Mean and True Motion Equinoctial Ecliptic Equinoxes Mean and True Longitude Equation of Center Inclination of the Orbits of Planets Celestial Latitude Nodes Elements of an Orbit Undisturbed or Elliptical Orbits Great Inclination of the Orbits of the new Planets Universal Gravitation the Cause of Perturbations in the Motions of the Heavenly Bodies Problem of the Three Bodies Stability of Solar System depends upon the Primitive Momentum of the Bodies 1 Section III. ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. …………………12 Perturbations, Periodic and Circular Disturbing Action equivalent to three Partial Forces Tangential force the Cause of the Periodic Inequalities in Longitude, and Secular Inequalities in the Form and Position of the Orbit in its own Plane Radial Force the Cause of Variations in the Planet’s distance from the Sun It combines with the Tangential Force to produce the Secular Variations in the Form and Position of the Orbit in its own Plane Perpendicular Force the Cause of Periodic Perturbations in Latitude, and Secular Variations in the Position of the Orbit with regard to the Plane of the Ecliptic Mean Motion and Major Axis Invariable Stability of System Effects of a Resisting Medium Invariable Plane of the Solar System and of the Universe Great Inequality of Jupiter and Saturn Section IV. -

The 100 Most Influential Scientists of All Time / Edited by Kara Rogers.—1St Ed

Published in 2010 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010. Copyright © 2010 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved. Rosen Educational Services materials copyright © 2010 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services. For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932. First Edition Britannica Educational Publishing Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition Kara Rogers: Senior Editor, Biomedical Sciences Rosen Educational Services Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor Nelson Sá: Art Director Introduction by Kristi Lew Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The 100 most influential scientists of all time / edited by Kara Rogers.—1st ed. p. cm.—(The Britannica guide to the world’s most influential people) “In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.” Includes index. ISBN 978-1-61530-040-2 (eBook) 1. Science—Popular works. 2. Science—History—Popular works. 3. Scientists— Biography—Popular works. I. Rogers, Kara. -

Science I, Scope & Sequence

Science I—Weekly Subject List Week Subject History Reference Aerodynamic shapes; engineering; Force = surface area * pressure * coef- 1 Thales / Aristotle Leads the Way, pp. 36-43 ficient of drag; Newtons Atomic structure; electron shells; static electricity; electron affinity; fric- 2 Thales / Aristotle, p. 38 tion; electron transfer; hypotheses Mass; weight; F=m*a; gravity; g=9.8m/s²; the effect of horizontal motion 3 Aristotle, Newton / Aristotle, pp. 94-105 on a freefalling object 4 Hydraulics; mechanical advantage; Pressure = Force / Area Hero of Alexandria / Aristotle, pp. 130-135 Basic machines; lever, pulley, wedge, wheel and axle, screw, inclined plane; 5 Mechanical Advantage of Wheel and Axle = Radius of Wheel/Radius of Hero of Alexandria / Aristotle, pp. 130-135 Axle Basic machines; First-class levers; mechanical advantage; Mass 1 * Distance 6 Archimedes / Aristotle, pp. 146-159 1 = Mass 2 * Distance 2 7 Compound Machines; inclined plan and screw; Archimedes’ Screw; Archimedes / Aristotle, pp. 146-159 Density = Mass / Volume; intrinsic value of coins; finding volume using 8 Archimedes / Aristotle, pp. 150-153 water displacement; reading a meniscus Compound Machines; wheel and axle; inclined plane; Work = Force * Filippo Brunelleschi / Newton at the Center, 9 Distance p. 7 10 Bridge efficiency; Da Vinci self-supporting bridge Leonardo Da Vinci / Newton p. 33 Pendulums; periods and cycles; effect of weight and length of pendulum 11 Galileo Galilei / Newton pp. 65-66 on the period; Period = 2 * ∏ l/g Telescopes; concave and convex lenses; radius of a lens; focus of a lens; 12 Galileo, Newton, Digges / Newton p. 108 angles of incidence and refraction Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation; F = G * (m1*m2/r2); F=m*a; g = 9.8 13 m/s²; although objects drop at the same rate, objects with more mass can Isaac Newton / Newton pp. -

(1991) 17 Faraday's Election to the Royal Society

ll. t. Ch. ( 17 References and Notes ntbl pnt n th lhtt dplnt ll th prtl thr t rd fr r pprh 0. It hld b phzd tht, fr 1. H. n n, The Life and Letters of Faraday, 2 l,, vh, th t r fndntl prtl nd tht hl nn, Grn C,, ndn, 86, t r pnd f th h plx pttrn f fr 2. , ndll, Faraday as a Discoverer, nn, Grn ld b d t nt fr "ltv ffnt" nd fr th rlrt C., ndn, 868, f rtl. , Gldtn, Michael Faraday, Mlln, ndn, . A, Faraday as a Natural Philosopher, Unvrt f 82, Ch, Ch, I, , 4. Sn I rd th ppr t th ACS, I hv xnd ll th 2. Gdn nd , , d., Faraday Rediscovered, vl f th Mechanics Magazine nd d nt fnd th lttr Mlln, ndn, 8, Gldtn ntnd. t hv nfd th zn th . G, Cntr, Michael Faraday: Sandemanian and Scientist, nthr jrnl tht I hv nt dvrd. Mlln, ndn, , . S, , hpn, Michael Faraday: His Life and Work, Mlln, Yr, Y, 88, 6. Mrtn, d,, Faraday's Diary (1820-1862),7 l., ll, L, Pearce Williams is John Stambaugh Professor of the ndn, 6. History of Science at Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850 . Wll, Michael Faraday, A Biography, Chpn and is author of "Michael Faraday, A Biography" and "The ll, ndn, 6, Origins of Field Theory" He has also edited two volumes of 8. M. rd, Experimental Researches in Electricity, l,, "The Selected Correspondence of Michael Faraday" Qrth, ndn, 88, l , p, . 9. Ibid., l, 2, p. -

– by Julia Cipo, Holger Kersten –

THE GAS DISCHARGE PHYSICS IN THE 19th CENTURY (PART I) – by Julia Cipo, Holger Kersten – Sir Vasily Humphry Petrov * July 19th, 1761 in Oboyan, Russia Davy † August 5th, 1834 in Saint Petersburg, Russia * December 17th, 1778 in Penzance, Cornwall in England Vasily Vladimirovich Petrov was a russian physicist and member of the Russian † May 29th, 1829 in Genf, Switzerland *4 Academy of Sciences. After A.Volta introduced his voltaic battery in the year *1 1800, Petrov began constructing a larger battery by using 4200 copper and zinc Sir Humphry Davy was an english chemist, inventor and presi- discs, stowed in four huge boxes. The boxes were about 3 m long and placed dent of the Royal Society. Unaware of Petrov’s work, Davy con- parallel to each other. They alternately ended with zinc and copper, so when structed a larger voltaic battery with an electrode area of 80 m2. connected they could be used as a serial circuit of Using his huge battery in 1807 he could decompose potash and 4200 electric cells. The motivation of building an soda by gaining the metals potassium and sodium. Later he could “enormous” battery as called by Petrov was the obtain barium, calcium, strontium and magnesium. During these observation of new effects. In his report of the experiments he experienced new gas discharge phenomena such year 1803 “Announcements on Galvano-Volta- as continuous arcs, which he presented often in front of a large ic experiments” he describes the observation of aristocratic audience. In his Bakerian Lecture he writes: “By the ar- *5 the fi rst continuous arc discharge.