(1991) 17 Faraday's Election to the Royal Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optical Timeline by Tony Oursler

Optical Timeline by Tony Oursler 1 Iris is thought to be derived from the RED Symyaz leads the fallen angels. Archimedes (c. 287212 b.c.) is said to Greek word for speaker or messenger. According to Enoch, they came to earth have used a large magnifying lens or Seth, the Egyptian god most associated of their own free will at Mount Hermon, burning-glass, which focused the suns Fifth century b.c. Chinese philosopher with evil, is depicted in many guises: descending like stars. This description rays, to set fire to Roman ships off Mo Ti, in the first description of the gives rise to the name Lucifer, “giver of Syracuse. camera obscura, refers to the pinhole as a black pig, a tall, double-headed figure light.” “collection place” and “locked treasure with a snout, and a serpent. Sometimes And now there is no longer any “I have seen Satan fall like lightning room.” he is black, a positive color for the difficulty in understanding the images in from heaven.” (Luke 10:1820) Egyptians, symbolic of the deep tones of mirrors and in all smooth and bright Platos Cave depicts the dilemma of fertile river deposits; at other times he is surfaces. The fires from within and from the uneducated in a graphic tableau of red, a negative color reflected by the without communicate about the smooth light and shadow. The shackled masses parched sands that encroach upon the surface, and from one image which is are kept in shadow, unable to move crops. Jeffrey Burton Russell suggests variously refracted. -

Formal and Informal Networks of Knowledge and Etheldred Benett's

Journal of Literature and Science Volume 8, No. 1 (2015) ISSN 1754-646X Susan Pickford, “Social Authorship, Networks of Knowledge”: 69-85 “I have no pleasure in collecting for myself alone”:1 Social Authorship, Networks of Knowledge and Etheldred Benett’s Catalogue of the Organic Remains of the County of Wiltshire (1831) Susan Pickford As with many other fields of scientific endeavour, the relationship between literature and geology has proved a fruitful arena for research in recent years. Much of this research has focused on the founding decades of the earth sciences in the early- to mid-nineteenth century, with recent articles by Gowan Dawson and Laurence Talairach-Vielmas joining works such as Noah Heringman’s Romantic Rocks, Aesthetic Geology (2003), Ralph O’Connor’s The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (2007), Virginia Zimmerman’s Excavating Victorians (2008) and Adelene Buckland’s Novel Science: Fiction and the Invention of Nineteenth-Century Geology (2013), to explore the rhetorical and narrative strategies of writings in the early earth sciences. It has long been noted that the most institutionally influential early geologists formed a cohort of eager young men who, having no tangible interests in the economic and practical applications of their chosen field, were in a position to develop a passionately Romantic engagement with nature, espousing an apocalyptic rhetoric of catastrophes past and borrowing epic imagery from Milton and Dante (Buckland 9, 14-15). However, as Buckland further notes, this argument – though persuasive as far as it goes – fails to take into account the broad social range of participants in the construction of early geological knowledge. -

Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary Journal Item How to cite: Stenhouse, Brigitte (2020). Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary. The Mathematical Intelligencer (Early Access). For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2020 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1007/s00283-020-09998-6 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary BRIGITTE STENHOUSE ary Somerville’s life as a mathematician and mathematician). Although no scientific learned society had a savant in nineteenth-century Great Britain was formal statute barring women during Somerville’s lifetime, MM heavily influenced by her gender; as a woman, there was nonetheless a great reluctance even toallow women her access to the ideas and resources developed and into the buildings, never mind to endow them with the rights circulated in universities and scientific societies was highly of members. Except for the visit of the prolific author Margaret restricted. However, her engagement with learned institu- Cavendish in 1667, the Royal Society of London did not invite tions was by no means nonexistent, and although she was women into their hallowed halls until 1876, with the com- 90 before being elected a full member of any society mencement of their second conversazione [15, 163], which (Societa` Geografica Italiana, 1870), Somerville (Figure 1) women were permitted to attend.1 As late as 1886, on the nevertheless benefited from the resources and social nomination of Isis Pogson as a fellow, the Council of the Royal networks cultivated by such institutions from as early as Astronomical Society chose to interpret their constitution as 1812. -

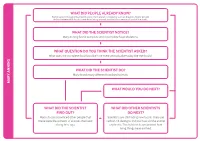

What Did the Scientist Notice? What Question Do You Think

WHAT DID PEOPLE ALREADY KNOW? Some people thought that fossils came from ancient creatures such as dragons. Some people did not believe that fossils came from living animals or plants but were just part of the rocks. WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST NOTICE? Mary Anning found complete and incomplete fossil skeletons. WHAT QUESTION DO YOU THINK THE SCIENTIST ASKED? What does the complete fossil look like? Are there animals alive today like the fossils? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST DO? Mary found many different fossilised animals. MARY ANNING MARY WHAT WOULD YOU DO NEXT? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST WHAT DID OTHER SCIENTISTS FIND OUT? DO NEXT? Mary’s fossils convinced other people that Scientists are still finding new fossils. They use these were the remains of animals that lived carbon-14 dating to find out how old the animal a long time ago. or plant is. This helps us to understand how living things have evolved. s 1823 / 1824 1947 Mary Anning (1823) discovered a nearly complete plesiosaur Carbon-14 dating enables scientists to determine the age of a formerly skeleton at Lyme Regis. living thing more accurately. When a Tail fossils of a baby species William Conybeare (1824) living organism dies, it stops taking in of Coelurosaur, fully People often found fossils on the beach described Mary’s plesiosaur to the new carbon. Measuring the amount preserved in amber including and did not know what they were, so Geographical Society. They debated of 14C in a fossil sample provides soft tissue, were found in 2016 BEFORE 1800 BEFORE gave them interesting names such as whether it was a fake, but Mary was information that can be used to Myanmar. -

A Short History of the Royal Aeronautical Society

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE ROYAL AERONAUTICAL SOCIETY Royal Aeronautical Society Council Dinner at the Science Museum on 26 May 1932 with Guest of Honour Miss Amelia Earhart. Edited by Chris Male MRAeS Royal Aeronautical Society www.aerosociety.com Afterburner Society News RAeS 150th ANNIVERSARY www.aerosociety.com/150 The Royal Aeronautical Society: Part 1 – The early years The Beginning “At a meeting held at Argyll Lodge, Campden Hill, Right: The first Aeronautical on 12 January 1866, His Grace The Duke of Argyll Exhibition, Crystal Palace, 1868, showing the presiding; also present Mr James Glaisher, Dr Hugh Stringfellow Triplane model W. Diamond, Mr F.H. Wenham, Mr James Wm. Butler and other exhibits. No fewer and Mr F.W. Brearey. Mr Glaisher read the following than 77 exhibits were address: collected together, including ‘The first application of the Balloon as a means of engines, lighter- and heavier- than-air models, kites and ascending into the upper regions of the plans of projected machines. atmosphere has been almost within the recollection A special Juror’s Report on on ‘Aerial locomotion and the laws by which heavy of men now living but with the exception of some the exhibits was issued. bodies impelled through air are sustained’. of the early experimenters it has scarcely occupied Below: Frederick W Brearey, Wenham’s lecture is now one of the aeronautical Secretary of the the attention of scientific men, nor has the subject of Aeronautical Society of Great classics and was the beginning of the pattern of aeronautics been properly recognised as a distinct Britain, 1866-1896. -

Humphry Davy: Science, Authorship, and the Changing Romantic

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2010-11-29 Humphry Davy: Science, Authorship, and the Changing Romantic Marianne Lind Baker Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Baker, Marianne Lind, "Humphry Davy: Science, Authorship, and the Changing Romantic" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 2647. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2647 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Page Humphry Davy: Science, Authorship, and the Changing ―Romantic I‖ Marianne Lind Baker A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Nicholas Mason, Chair Leslee Thorne-Murphy Paul Westover Department of English Brigham Young University December 2010 Copyright © 2010 Marianne Baker All Rights Reserved Abstract ABSTRACT Humphry Davy: Science, Authorship, and the Changing ―Romantic I‖ Marianne Lind Baker Department of English Master of Arts In the mid to late 1700s, men of letters became more and more interested in the natural world. From studies in astronomy to biology, chemistry, and medicine, these ―philosophers‖ pioneered what would become our current scientific categories. While the significance of their contributions to these fields has been widely appreciated historically, the interconnection between these men and their literary counterparts has not. A study of the ―Romantic man of science‖ reveals how much that figure has in common with the traditional ―Romantic‖ literary figure embodied by poets like William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. -

Doctorat Honoris Causa

DOCTORAT HONORIS CAUSA Acord núm. 204/2007 del Consell de Govern, pel qual s’aprova la concessió del doctorat Honoris Causa al Professor Sir Michael Atiyah. Document aprovat per la Comissió Permanent del dia 3/12/2007. Document aprovat pel Consell de Govern del dia 17/12/2007. DOCUMENT CG 14/12 2007 Secretaria General Desembre de 2007 PROPOSTA D’ACORD DEL CONSELL DE GOVERN PER A CONCEDIR EL DOCTORAT HONORIS CAUSA PER LA UNIVERSITAT POLITÈCNICA DE CATALUNYA, AL PROFESSOR SIR MICHAEL ATIYAH ANTECEDENTS: 1. El professor Sir Michael Atiyah ha estat guardonat, entre d’altres distincions, amb la Medalla Fields (1966), atorgada per la Unió Matemàtica Internacional, i el Premi Abel (2004), atorgat per l’Acadèmia de Ciències de Noruega, ambdues reconegudes com un Premi Nobel de les Matemàtiques. També ha estat un dels impulsors més decisius de la Societat Matemàtica Europea. 2. En relació amb Catalunya i Barcelona, i més concretament, amb la UPC, el professor Sir Michael Atiyah ha estat president del Comitè Científic del 3r Congrés Europeu de Matemàtiques celebrat a Barcelona l’any 2000. 3. El prestigi internacional del professor Sir Michael Atiyah el fa un candidat idoni com a primer doctor honoris causa per la UPC en un àrea en la qual la nostra Universitat compta amb una comunitat nombrosa i amb un gran prestigi i reconeixement internacionals. 4. El rector ha rebut una proposta formal per a investir el professor Sir Michael Atiyah com a doctor honoris causa per la Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, signada pel degà de la Facultat de Matemàtiques i Estadística, el director del departament de Matemàtica Aplicada I, el director del departament de Matemàtica Aplicada II, el director del departament de Matemàtica Aplicada III, el director del departament de Matemàtica Aplicada IV, i el director del departament d’Estadística i Investigació Operativa. -

Philosophical Transactions, »

INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS, » S e r ie s A, FOR THE YEAR 1898 (VOL. 191). A. Absorption, Change of, produced by Fluorescence (B urke), 87. Aneroid Barometers, Experiments on.—Elastic After-effect; Secular Change; Influence of Temperature (Chree), 441. B. Bolometer, Surface, Construction of (Petavel), 501. Brilliancy, Intrinsic, Law of Variation of, with Temperature (Petavel), 501. Burke (John). On the Change of Absorption produced by Fluorescence, 87. C. Chree (C.). Experiments on Aneroid Barometers at Kew Observatory, and their Discussion, 441. Correlation and Variation, Influence of Random Selection on (Pearson and Filon), 229. Crystals, Thermal Expansion Coefficients, by an Interference Method (Tutton), 313. D. Differential Equations of the Second Order, &c., Memoir on the Integration of; Characteristic Invariant of (Forsyth), 1. 526 INDEX. E. Electric Filters, Testing Efficiency of; Dielectrifying Power of (Kelvin, Maclean, and Galt), 187. Electricity, Diffusion of, from Carbonic Acid Gas to Air; Communication of, from Electrified Steam to Air (Kelvin, Maclean, and Galt), 187. Electrification of Air by Water Jet, Electrified Needle Points, Electrified Flame, &c., at Different Air-pressures; at Different Electrifying Potentials; Loss of Electrification (Kelvin, Maclean, and Galt), 187. Electrolytic Cells, Construction and Calibration of (Veley and Manley), 365. Emissivity of Platinum in Air and other Gases (Petavel), 501. Equations, Laplace's and other, Some New Solutions of, in Mathematical Physics (Forsyth), 1. Evolution, Mathematical Contributions to Theory o f; Influence of Random Selection on the Differentiation of Local Races (Pearson and Filon), 229. F. Filon (L. N. G.) and Pearson (Karl). Mathematical Contributions to the Theory of Evolution.—IV. On the Probable Errors of Frequency Constants and on the Influence of Random Selection on Variation and Correlation, 229. -

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1 CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 2 License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy Author: George Biddell Airy Release Date: January 9, 2004 [EBook #10655] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR GEORGE AIRY *** Produced by Joseph Myers and PG Distributed Proofreaders AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., M.A., LL.D., D.C.L., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., HONORARY FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, ASTRONOMER ROYAL FROM 1836 TO 1881. EDITED BY WILFRID AIRY, B.A., M.Inst.C.E. 1896 PREFACE. The life of Airy was essentially that of a hard-working, business man, and differed from that of other hard-working people only in the quality and variety of his work. It was not an exciting life, but it was full of interest, and his work brought him into close relations with many scientific men, and with many men high in the State. -

Further Reading: Michael Faraday

Further Reading: Michael Faraday General reading Geoffrey Cantor, Michael Faraday: Sandemanian and Scientist. A Study of Science and Religion in the Nineteenth Century, (London, 1991). David Gooding, Experiment and the Making of Meaning: Human Agency in Scientific Observation and Experiment, (Dordrecht, 1991). David Gooding and Frank A.J.L. James (eds.), Faraday Rediscovered: Essays on the Life and Work of Michael Faraday, 1791‐1867, (London, 1985). Frank A.J.L. James (ed.), ‘The Common Purposes of Life’: Science and society at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, (Aldershot, 2002). Frank A.J.L. James, Michael Faraday: A very short Introduction. (Oxford, 2010) Alan E. Jeffreys, Michael Faraday: A List of His Lectures and Published Writings, (London, 1960). Published books by Faraday, mainly collections of papers and lecture notes, some published after his death: Chemical Manipulation, Being Instructions to Students in Chemistry. (1827). Experimental Researches in Electricity, Vol I, II& III (1837, 1844, 1855) Experimental Researches in Chemistry and Physics (1859). W. Crookes. ed. A Course of six lectures on the Various Forces of Matter (1860) W. Crookes. ed. A Course of six lectures on the Chemical History of a Candle, (1861) W. Crookes. ed. On the Various Forces in Nature. (1873) The liquefaction of gases (1896.) Published texts by Faraday The vast majority of Faraday’s manuscripts, apart from letters, have been published on microfilm and cd. Frank A.J.L. James, Guide to the Microfilm edition of the Manuscripts of Michael Faraday (1791‐1867) from the Collections of the Royal Institution, The Institution of Electrical Engineers, The Guildhall Library [and] The Royal Society, (2nd ed., Wakefield, 2001). -

Evidence Synthesis on the EU-UK Relationship on Research and Innovation January 2018

Evidence synthesis on the EU-UK relationship on research and innovation January 2018 1. Introduction The Royal Society and the Wellcome Trust have undertaken a rapid evidence synthesis on the EU-UK research and innovation relationship as part of their Future Partnership Project. Organisations and individuals were invited to submit evidence and analyses for inclusion. Evidence was also gathered through internet searches to ensure an inclusive approach. The Annex is a summary of the methods. Two questions were used in gathering evidence and in determining the material in scope: 1. What incentives, infrastructure and mechanisms can be accessed by research and innovation organisations, funders and individuals in Member States to support collaborations? 2. How do Member States currently use and benefit from these and how might they be affected by Brexit? This paper is a synthesis of the evidence and covers funding, infrastructures, mobility, collaboration and regulation, with a focus on links between the EU and the UK. 2. Overview of the evidence base A few major reports were of particular relevance; the Royal Society’s three reports on the role of the EU in UK research and innovation and two reports commissioned from Technopolis Group by UK organisations, on the role of EU funding in UK research and innovation and the impact of collaboration: the value of UK medical research to EU science and health1,2. These documents were often referenced in other submissions. A report from the Lords Science and Technology Committee’s inquiry on EU Membership and UK Science also summarises many sources of evidence relevant to this synthesis. -

Common Acronyms Engineers SOE Society of Operations Engineers Licensed Members TWI the Welding Institute BCS the Chartered Institute for IT

SEE Society of Environmental Common Acronyms Engineers SOE Society of Operations Engineers Licensed Members TWI The Welding Institute BCS The Chartered Institute for IT BINDT British Institute of Non-Destructive Testing Professional Affiliates CIBSE Chartered Institution of Building ACostE Association of Cost Engineers Services Engineers APM Association for Project CIHT Chartered Institution of Highways Management and Transportation CABE Chartered Association of Building CIPHE Chartered Institute of Plumbing and Engineers Heating Engineering CQI Chartered Quality Institute CIWEM Chartered Institution of Water and IAEA Institute of Automotive Engineer Environmental Management Assessors EI Energy Institute IAT Institute of Asphalt Technology IAgrE Institution of Agricultural Engineers ICES Chartered Institution of Civil ICE Institution of Civil Engineers Engineering Surveyors IChemE Institution of Chemical Engineers ICorr Institute of Corrosion ICME Institute of Cast Metals Engineers ICT Institute of Concrete Technology IED Institution of Engineering IDE Institute of Demolition Engineers Designers IDGTE Institution of Diesel and Gas IET Institution of Engineering and Turbine Engineers Technology IExpE Institute of Explosives Engineers IFE Institution of Fire Engineers IMA Institute of Mathematics and its IGEM Institution of Gas Engineers and Applications Managers IMF Institute of Materials Finishing IHE Institute of Highway Engineers INCOSE UK International Council on Systems Engineering (UK Chapter) IHEEM Institute of Healthcare Engineering