Magnetic Immunity of the MRAM Devices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Covariant Representation of Integral Equations of the Electromagnetic Field

On the covariant representation of integral equations of the electromagnetic field Sergey G. Fedosin PO box 614088, Sviazeva str. 22-79, Perm, Perm Krai, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Gauss integral theorems for electric and magnetic fields, Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction, magnetic field circulation theorem, theorems on the flux and circulation of vector potential, which are valid in curved spacetime, are presented in a covariant form. Covariant formulas for magnetic and electric fluxes, for electromotive force and circulation of the vector potential are provided. In particular, the electromotive force is expressed by a line integral over a closed curve, while in the integral, in addition to the vortex electric field strength, a determinant of the metric tensor also appears. Similarly, the magnetic flux is expressed by a surface integral from the product of magnetic field induction by the determinant of the metric tensor. A new physical quantity is introduced – the integral scalar potential, the rate of change of which over time determines the flux of vector potential through a closed surface. It is shown that the commonly used four-dimensional Kelvin-Stokes theorem does not allow one to deduce fully the integral laws of the electromagnetic field and in the covariant notation requires the addition of determinant of the metric tensor, besides the validity of the Kelvin-Stokes theorem is limited to the cases when determinant of metric tensor and the contour area are independent from time. This disadvantage is not present in the approach that uses the divergence theorem and equation for the dual electromagnetic field tensor. -

Units and Magnitudes (Lecture Notes)

physics 8.701 topic 2 Frank Wilczek Units and Magnitudes (lecture notes) This lecture has two parts. The first part is mainly a practical guide to the measurement units that dominate the particle physics literature, and culture. The second part is a quasi-philosophical discussion of deep issues around unit systems, including a comparison of atomic, particle ("strong") and Planck units. For a more extended, profound treatment of the second part issues, see arxiv.org/pdf/0708.4361v1.pdf . Because special relativity and quantum mechanics permeate modern particle physics, it is useful to employ units so that c = ħ = 1. In other words, we report velocities as multiples the speed of light c, and actions (or equivalently angular momenta) as multiples of the rationalized Planck's constant ħ, which is the original Planck constant h divided by 2π. 27 August 2013 physics 8.701 topic 2 Frank Wilczek In classical physics one usually keeps separate units for mass, length and time. I invite you to think about why! (I'll give you my take on it later.) To bring out the "dimensional" features of particle physics units without excess baggage, it is helpful to keep track of powers of mass M, length L, and time T without regard to magnitudes, in the form When these are both set equal to 1, the M, L, T system collapses to just one independent dimension. So we can - and usually do - consider everything as having the units of some power of mass. Thus for energy we have while for momentum 27 August 2013 physics 8.701 topic 2 Frank Wilczek and for length so that energy and momentum have the units of mass, while length has the units of inverse mass. -

Weberˇs Planetary Model of the Atom

Weber’s Planetary Model of the Atom Bearbeitet von Andre Koch Torres Assis, Gudrun Wolfschmidt, Karl Heinrich Wiederkehr 1. Auflage 2011. Taschenbuch. 184 S. Paperback ISBN 978 3 8424 0241 6 Format (B x L): 17 x 22 cm Weitere Fachgebiete > Physik, Astronomie > Physik Allgemein schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Weber’s Planetary Model of the Atom Figure 0.1: Wilhelm Eduard Weber (1804–1891) Foto: Gudrun Wolfschmidt in der Sternwarte in Göttingen 2 Nuncius Hamburgensis Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften Band 19 Andre Koch Torres Assis, Karl Heinrich Wiederkehr and Gudrun Wolfschmidt Weber’s Planetary Model of the Atom Ed. by Gudrun Wolfschmidt Hamburg: tredition science 2011 Nuncius Hamburgensis Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften Hg. von Gudrun Wolfschmidt, Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Mathematik und Technik, Universität Hamburg – ISSN 1610-6164 Diese Reihe „Nuncius Hamburgensis“ wird gefördert von der Hans Schimank-Gedächtnisstiftung. Dieser Titel wurde inspiriert von „Sidereus Nuncius“ und von „Wandsbeker Bote“. Andre Koch Torres Assis, Karl Heinrich Wiederkehr and Gudrun Wolfschmidt: Weber’s Planetary Model of the Atom. Ed. by Gudrun Wolfschmidt. Nuncius Hamburgensis – Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 19. Hamburg: tredition science 2011. Abbildung auf dem Cover vorne und Titelblatt: Wilhelm Weber (Kohlrausch, F. (Oswalds Klassiker Nr. 142) 1904, Frontispiz) Frontispiz: Wilhelm Weber (1804–1891) (Feyerabend 1933, nach S. -

The Concept of Field in the History of Electromagnetism

The concept of field in the history of electromagnetism Giovanni Miano Department of Electrical Engineering University of Naples Federico II ET2011-XXVII Riunione Annuale dei Ricercatori di Elettrotecnica Bologna 16-17 giugno 2011 Celebration of the 150th Birthday of Maxwell’s Equations 150 years ago (on March 1861) a young Maxwell (30 years old) published the first part of the paper On physical lines of force in which he wrote down the equations that, by bringing together the physics of electricity and magnetism, laid the foundations for electromagnetism and modern physics. Statue of Maxwell with its dog Toby. Plaque on E-side of the statue. Edinburgh, George Street. Talk Outline ! A brief survey of the birth of the electromagnetism: a long and intriguing story ! A rapid comparison of Weber’s electrodynamics and Maxwell’s theory: “direct action at distance” and “field theory” General References E. T. Wittaker, Theories of Aether and Electricity, Longam, Green and Co., London, 1910. O. Darrigol, Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einste in, Oxford University Press, 2000. O. M. Bucci, The Genesis of Maxwell’s Equations, in “History of Wireless”, T. K. Sarkar et al. Eds., Wiley-Interscience, 2006. Magnetism and Electricity In 1600 Gilbert published the “De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure” (On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on That Great Magnet the Earth). ! The Earth is magnetic ()*+(,-.*, Magnesia ad Sipylum) and this is why a compass points north. ! In a quite large class of bodies (glass, sulphur, …) the friction induces the same effect observed in the amber (!"#$%&'(, Elektron). Gilbert gave to it the name “electricus”. -

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1. A. Pre-1820. (1) Electrostatics (frictional electricity) • 1780s. Coulomb's description: ! Two electric fluids: positive and negative. ! Inverse square law: It follows therefore from these three tests, that the repulsive force that the two balls -- [which were] electrified with the same kind of electricity -- exert on each other, Charles-Augustin de Coulomb follows the inverse proportion of (1736-1806) the square of the distance."" (2) Magnetism: Coulomb's description: • Two fluids ("astral" and "boreal") obeying inverse square law. • No magnetic monopoles: fluids are imprisoned in molecules of magnetic bodies. (3) Galvanism • 1770s. Galvani's frog legs. "Animal electricity": phenomenon belongs to biology. • 1800. Volta's ("volatic") pile. Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) • Pile consists of alternating copper and • Charged rod connected zinc plates separated by to inner foil. brine-soaked cloth. • Outer foil grounded. • A "battery" of Leyden • Inner and outer jars that can surfaces store equal spontaeously recharge but opposite charges. themselves. 1745 Leyden jar. • Volta: Pile is an electric phenomenon and belongs to physics. • But: Nicholson and Carlisle use voltaic current to decompose Alessandro Volta water into hydrogen and oxygen. Pile belongs to chemistry! (1745-1827) • Are electricity and magnetism different phenomena? ! Electricity involves violent actions and effects: sparks, thunder, etc. ! Magnetism is more quiet... Hans Christian • 1820. Oersted's Experimenta circa effectum conflictus elecrici in Oersted (1777-1851) acum magneticam ("Experiments on the effect of an electric conflict on the magnetic needle"). ! Galvanic current = an "electric conflict" between decompositions and recompositions of positive and negative electricities. ! Experiments with a galvanic source, connecting wire, and rotating magnetic needle: Needle moves in presence of pile! "Otherwise one could not understand how Oersted's Claims the same portion of the wire drives the • Electric conflict acts on magnetic poles. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

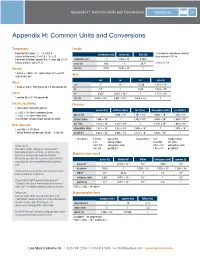

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215 Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Temperature Length Fahrenheit to Celsius: °C = (°F-32)/1.8 1 micrometer (sometimes referred centimeter (cm) meter (m) inch (in) Celsius to Fahrenheit: °F = (1.8 × °C) + 32 to as micron) = 10-6 m Fahrenheit to Kelvin: convert °F to °C, then add 273.15 centimeter (cm) 1 1.000 × 10–2 0.3937 -3 Celsius to Kelvin: add 273.15 meter (m) 100 1 39.37 1 mil = 10 in Volume inch (in) 2.540 2.540 × 10–2 1 –3 3 1 liter (l) = 1.000 × 10 cubic meters (m ) = 61.02 Area cubic inches (in3) cm2 m2 in2 circ mil Mass cm2 1 10–4 0.1550 1.974 × 105 1 kilogram (kg) = 1000 grams (g) = 2.205 pounds (lb) m2 104 1 1550 1.974 × 109 Force in2 6.452 6.452 × 10–4 1 1.273 × 106 1 newton (N) = 0.2248 pounds (lb) circ mil 5.067 × 10–6 5.067 × 10–10 7.854 × 10–7 1 Electric resistivity Pressure 1 micro-ohm-centimeter (µΩ·cm) pascal (Pa) millibar (mbar) torr (Torr) atmosphere (atm) psi (lbf/in2) = 1.000 × 10–6 ohm-centimeter (Ω·cm) –2 –3 –6 –4 = 1.000 × 10–8 ohm-meter (Ω·m) pascal (Pa) 1 1.000 × 10 7.501 × 10 9.868 × 10 1.450 × 10 = 6.015 ohm-circular mil per foot (Ω·circ mil/ft) millibar (mbar) 1.000 × 102 1 7.502 × 10–1 9.868 × 10–4 1.450 × 10–2 2 0 –3 –2 Heat flow rate torr (Torr) 1.333 × 10 1.333 × 10 1 1.316 × 10 1.934 × 10 5 3 2 1 1 watt (W) = 3.413 Btu/h atmosphere (atm) 1.013 × 10 1.013 × 10 7.600 × 10 1 1.470 × 10 1 British thermal unit per hour (Btu/h) = 0.2930 W psi (lbf/in2) 6.897 × 103 6.895 × 101 5.172 × 101 6.850 × 10–2 1 1 torr (Torr) = 133.332 pascal (Pa) 1 pascal (Pa) = 0.01 millibar (mbar) 1.33 millibar (mbar) 0.007501 torr (Torr) –6 A Note on SI 0.001316 atmosphere (atm) 9.87 × 10 atmosphere (atm) 2 –4 2 The values in this catalog are expressed in 0.01934 psi (lbf/in ) 1.45 × 10 psi (lbf/in ) International System of Units, or SI (from the Magnetic induction B French Le Système International d’Unités). -

Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1970 Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System Herman G. Hamre Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Hamre, Herman G., "Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System" (1970). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3780. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/3780 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUTOMATIC IRRIGATION: SENSORS AND SYSTEM BY HERMAN G. HAMRE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science, Major in Electrical Engineering, South Dakota State University 1970 SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY AUTOMATIC IRRIGATION: SENSORS AND SYSTEM This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investi gation by a candidate for the degree, Master of Science, and is accept able as meeting the thesis requirements for this degree, but without implying that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. �--- -"""'" _ _ -���--- - _ _ _ _____ -A>� - 7 7 T b � s/./ifjvisor ate Head, Electrical -r-oate Engineering Department ACKNOWLE GEMENTS The author wishes to express his sincere appreciation to Dr. A. J. Kurtenbach for his patient guidance and helpful suggestions, and to the Water Resources Institute for their support of this research. -

Electricity and Magnetism

Lecture 10 Fundamentals of Physics Phys 120, Fall 2015 Electricity and Magnetism A. J. Wagner North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58102 Fargo, September 24, 2015 Overview • Unexplained phenomena • Charges and electric forces revealed • Currents and circuits • Electricity and Magnetism are related! 1 Newton’s dream I wish we could derive the rest of the phenomena of Nature by the same kind of reasoning from mechanical principles, for I am induced by many reasons to suspect that they may all depend upon certain forces by which the particles of bodies, by some cause hitherto unknown, are either mutually impelled towards one another, and cohere in regular figures, or are repelled and recede from one another. from the preface of Newton’s Principia 2 What were those mysterious phenomena? 900 BC: Magnus, a Greek shepherd, walks across a field of black stones which pull the iron nails out of his sandals and the iron tip from his shepherd’s staff (authenticity not guaranteed). This region becomes known as Magnesia. 600 BC: Thales of Miletos(Greece) discovered that by rubbing an ’elektron’ (a hard, fossilized resin that today is known as amber) against a fur cloth, it would attract particles of straw and feathers. This strange effect remained a mystery for over 2000 years. 1269 AD: Petrus Peregrinus of Picardy, Italy, discovers that natural spherical magnets (lodestones) align needles with lines of longitude pointing between two pole positions on the stone. 3 ca. 1600: Dr.William Gilbert (court physician to Queen Elizabeth) discovers that the earth is a giant magnet just like one of the stones of Peregrinus, explaining how compasses work. -

Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 151. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/151 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 30 Magnetic Fields of Currents 30-1 Magnetic Field around an Electric Current The first evidence for the existence of a magnetic field around an electric current was observed in 1820 by Hans Christian Oersted (1777-1851). He found that a wire carrying current caused a freely pivoted compass needle B D N rDirection I of current D II. • ~ I I In wire ' \ N I I c , I s c (a) (b) Fig. 30-1 Oersted's experiment. Compass needle is deflected toward the west when the wire CD carrying current is placed above it and the direction of the current is toward the north, from C to D. in its vicinity to be deflected. If the current in a long straight wire is directed from C to D, as shown in Figure 30-1, a compass needle below it, whose initial orientation is shown in dotted lines, will have its north pole deflected to the left and its south pole deflected to the right. -

Units and Magnitudes (Lecture Notes)

physics 8.701 topic 2 Frank Wilczek Units and Magnitudes (lecture notes) This lecture has two parts. The first part is mainly a practical guide to the measurement units that dominate the particle physics literature, and culture. The second part is a quasi-philosophical discussion of deep issues around unit systems, including a comparison of atomic, particle ("strong") and Planck units. For a more extended, profound treatment of the second part issues, see arxiv.org/pdf/0708.4361v1.pdf . Because special relativity and quantum mechanics permeate modern particle physics, it is useful to employ units so that c = ħ = 1. In other words, we report velocities as multiples the speed of light c, and actions (or equivalently angular momenta) as multiples of the rationalized Planck's constant ħ, which is the original Planck constant h divided by 2π. 27 August 2013 physics 8.701 topic 2 Frank Wilczek In classical physics one usually keeps separate units for mass, length and time. I invite you to think about why! (I'll give you my take on it later.) To bring out the "dimensional" features of particle physics units without excess baggage, it is helpful to keep track of powers of mass M, length L, and time T without regard to magnitudes, in the form When these are both set equal to 1, the M, L, T system collapses to just one independent dimension. So we can - and usually do - consider everything as having the units of some power of mass. Thus for energy we have while for momentum 27 August 2013 physics 8.701 topic 2 Frank Wilczek and for length so that energy and momentum have the units of mass, while length has the units of inverse mass. -

Vocabulary of Magnetism

TECHNotes The Vocabulary of Magnetism Symbols for key magnetic parameters continue to maximum energy point and the value of B•H at represent a challenge: they are changing and vary this point is the maximum energy product. (You by author, country and company. Here are a few may have noticed that typing the parentheses equivalent symbols for selected parameters. for (BH)MAX conveniently avoids autocorrecting Subscripts in symbols are often ignored so as to the two sequential capital letters). Units of simplify writing and typing. The subscripted letters maximum energy product are kilojoules per are sometimes capital letters to be more legible. In cubic meter, kJ/m3 (SI) and megagauss•oersted, ASTM documents, symbols are italicized. According MGOe (cgs). to NIST’s guide for the use of SI, symbols are not italicized. IEC uses italics for the main part of the • µr = µrec = µ(rec) = recoil permeability is symbol, but not for the subscripts. I have not used measured on the normal curve. It has also been italics in the following definitions. For additional called relative recoil permeability. When information the reader is directed to ASTM A340[11] referring to the corresponding slope on the and the NIST Guide to the use of SI[12]. Be sure to intrinsic curve it is called the intrinsic recoil read the latest edition of ASTM A340 as it is permeability. In the cgs-Gaussian system where undergoing continual updating to be made 1 gauss equals 1 oersted, the intrinsic recoil consistent with industry, NIST and IEC usage. equals the normal recoil minus 1.