Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix A: Symbols and Prefixes

Appendix A: Symbols and Prefixes (Appendix A last revised November 2020) This appendix of the Author's Kit provides recommendations on prefixes, unit symbols and abbreviations, and factors for conversion into units of the International System. Prefixes Recommended prefixes indicating decimal multiples or submultiples of units and their symbols are as follows: Multiple Prefix Abbreviation 1024 yotta Y 1021 zetta Z 1018 exa E 1015 peta P 1012 tera T 109 giga G 106 mega M 103 kilo k 102 hecto h 10 deka da 10-1 deci d 10-2 centi c 10-3 milli m 10-6 micro μ 10-9 nano n 10-12 pico p 10-15 femto f 10-18 atto a 10-21 zepto z 10-24 yocto y Avoid using compound prefixes, such as micromicro for pico and kilomega for giga. The abbreviation of a prefix is considered to be combined with the abbreviation/symbol to which it is directly attached, forming with it a new unit symbol, which can be raised to a positive or negative power and which can be combined with other unit abbreviations/symbols to form abbreviations/symbols for compound units. For example: 1 cm3 = (10-2 m)3 = 10-6 m3 1 μs-1 = (10-6 s)-1 = 106 s-1 1 mm2/s = (10-3 m)2/s = 10-6 m2/s Abbreviations and Symbols Whenever possible, avoid using abbreviations and symbols in paragraph text; however, when it is deemed necessary to use such, define all but the most common at first use. The following is a recommended list of abbreviations/symbols for some important units. -

The Concept of Field in the History of Electromagnetism

The concept of field in the history of electromagnetism Giovanni Miano Department of Electrical Engineering University of Naples Federico II ET2011-XXVII Riunione Annuale dei Ricercatori di Elettrotecnica Bologna 16-17 giugno 2011 Celebration of the 150th Birthday of Maxwell’s Equations 150 years ago (on March 1861) a young Maxwell (30 years old) published the first part of the paper On physical lines of force in which he wrote down the equations that, by bringing together the physics of electricity and magnetism, laid the foundations for electromagnetism and modern physics. Statue of Maxwell with its dog Toby. Plaque on E-side of the statue. Edinburgh, George Street. Talk Outline ! A brief survey of the birth of the electromagnetism: a long and intriguing story ! A rapid comparison of Weber’s electrodynamics and Maxwell’s theory: “direct action at distance” and “field theory” General References E. T. Wittaker, Theories of Aether and Electricity, Longam, Green and Co., London, 1910. O. Darrigol, Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einste in, Oxford University Press, 2000. O. M. Bucci, The Genesis of Maxwell’s Equations, in “History of Wireless”, T. K. Sarkar et al. Eds., Wiley-Interscience, 2006. Magnetism and Electricity In 1600 Gilbert published the “De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure” (On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on That Great Magnet the Earth). ! The Earth is magnetic ()*+(,-.*, Magnesia ad Sipylum) and this is why a compass points north. ! In a quite large class of bodies (glass, sulphur, …) the friction induces the same effect observed in the amber (!"#$%&'(, Elektron). Gilbert gave to it the name “electricus”. -

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1. A. Pre-1820. (1) Electrostatics (frictional electricity) • 1780s. Coulomb's description: ! Two electric fluids: positive and negative. ! Inverse square law: It follows therefore from these three tests, that the repulsive force that the two balls -- [which were] electrified with the same kind of electricity -- exert on each other, Charles-Augustin de Coulomb follows the inverse proportion of (1736-1806) the square of the distance."" (2) Magnetism: Coulomb's description: • Two fluids ("astral" and "boreal") obeying inverse square law. • No magnetic monopoles: fluids are imprisoned in molecules of magnetic bodies. (3) Galvanism • 1770s. Galvani's frog legs. "Animal electricity": phenomenon belongs to biology. • 1800. Volta's ("volatic") pile. Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) • Pile consists of alternating copper and • Charged rod connected zinc plates separated by to inner foil. brine-soaked cloth. • Outer foil grounded. • A "battery" of Leyden • Inner and outer jars that can surfaces store equal spontaeously recharge but opposite charges. themselves. 1745 Leyden jar. • Volta: Pile is an electric phenomenon and belongs to physics. • But: Nicholson and Carlisle use voltaic current to decompose Alessandro Volta water into hydrogen and oxygen. Pile belongs to chemistry! (1745-1827) • Are electricity and magnetism different phenomena? ! Electricity involves violent actions and effects: sparks, thunder, etc. ! Magnetism is more quiet... Hans Christian • 1820. Oersted's Experimenta circa effectum conflictus elecrici in Oersted (1777-1851) acum magneticam ("Experiments on the effect of an electric conflict on the magnetic needle"). ! Galvanic current = an "electric conflict" between decompositions and recompositions of positive and negative electricities. ! Experiments with a galvanic source, connecting wire, and rotating magnetic needle: Needle moves in presence of pile! "Otherwise one could not understand how Oersted's Claims the same portion of the wire drives the • Electric conflict acts on magnetic poles. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

SI and CGS Units in Electromagnetism

SI and CGS Units in Electromagnetism Jim Napolitano January 7, 2010 These notes are meant to accompany the course Electromagnetic Theory for the Spring 2010 term at RPI. The course will use CGS units, as does our textbook Classical Electro- dynamics, 2nd Ed. by Hans Ohanian. Up to this point, however, most students have used the International System of Units (SI, also known as MKSA) for mechanics, electricity and magnetism. (I believe it is easy to argue that CGS is more appropriate for teaching elec- tromagnetism to physics students.) These notes are meant to smooth the transition, and to augment the discussion in Appendix 2 of your textbook. The base units1 for mechanics in SI are the meter, kilogram, and second (i.e. \MKS") whereas in CGS they are the centimeter, gram, and second. Conversion between these base units and all the derived units are quite simply given by an appropriate power of 10. For electromagnetism, SI adds a new base unit, the Ampere (\A"). This leads to a world of complications when converting between SI and CGS. Many of these complications are philosophical, but this note does not discuss such issues. For a good, if a bit flippant, on- line discussion see http://info.ee.surrey.ac.uk/Workshop/advice/coils/unit systems/; for a more scholarly article, see \On Electric and Magnetic Units and Dimensions", by R. T. Birge, The American Physics Teacher, 2(1934)41. Electromagnetism: A Preview Electricity and magnetism are not separate phenomena. They are different manifestations of the same phenomenon, called electromagnetism. One requires the application of special relativity to see how electricity and magnetism are united. -

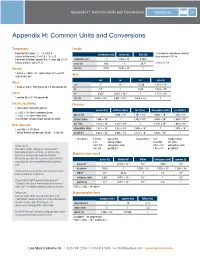

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215 Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Temperature Length Fahrenheit to Celsius: °C = (°F-32)/1.8 1 micrometer (sometimes referred centimeter (cm) meter (m) inch (in) Celsius to Fahrenheit: °F = (1.8 × °C) + 32 to as micron) = 10-6 m Fahrenheit to Kelvin: convert °F to °C, then add 273.15 centimeter (cm) 1 1.000 × 10–2 0.3937 -3 Celsius to Kelvin: add 273.15 meter (m) 100 1 39.37 1 mil = 10 in Volume inch (in) 2.540 2.540 × 10–2 1 –3 3 1 liter (l) = 1.000 × 10 cubic meters (m ) = 61.02 Area cubic inches (in3) cm2 m2 in2 circ mil Mass cm2 1 10–4 0.1550 1.974 × 105 1 kilogram (kg) = 1000 grams (g) = 2.205 pounds (lb) m2 104 1 1550 1.974 × 109 Force in2 6.452 6.452 × 10–4 1 1.273 × 106 1 newton (N) = 0.2248 pounds (lb) circ mil 5.067 × 10–6 5.067 × 10–10 7.854 × 10–7 1 Electric resistivity Pressure 1 micro-ohm-centimeter (µΩ·cm) pascal (Pa) millibar (mbar) torr (Torr) atmosphere (atm) psi (lbf/in2) = 1.000 × 10–6 ohm-centimeter (Ω·cm) –2 –3 –6 –4 = 1.000 × 10–8 ohm-meter (Ω·m) pascal (Pa) 1 1.000 × 10 7.501 × 10 9.868 × 10 1.450 × 10 = 6.015 ohm-circular mil per foot (Ω·circ mil/ft) millibar (mbar) 1.000 × 102 1 7.502 × 10–1 9.868 × 10–4 1.450 × 10–2 2 0 –3 –2 Heat flow rate torr (Torr) 1.333 × 10 1.333 × 10 1 1.316 × 10 1.934 × 10 5 3 2 1 1 watt (W) = 3.413 Btu/h atmosphere (atm) 1.013 × 10 1.013 × 10 7.600 × 10 1 1.470 × 10 1 British thermal unit per hour (Btu/h) = 0.2930 W psi (lbf/in2) 6.897 × 103 6.895 × 101 5.172 × 101 6.850 × 10–2 1 1 torr (Torr) = 133.332 pascal (Pa) 1 pascal (Pa) = 0.01 millibar (mbar) 1.33 millibar (mbar) 0.007501 torr (Torr) –6 A Note on SI 0.001316 atmosphere (atm) 9.87 × 10 atmosphere (atm) 2 –4 2 The values in this catalog are expressed in 0.01934 psi (lbf/in ) 1.45 × 10 psi (lbf/in ) International System of Units, or SI (from the Magnetic induction B French Le Système International d’Unités). -

Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1970 Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System Herman G. Hamre Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Hamre, Herman G., "Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System" (1970). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3780. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/3780 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUTOMATIC IRRIGATION: SENSORS AND SYSTEM BY HERMAN G. HAMRE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science, Major in Electrical Engineering, South Dakota State University 1970 SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY AUTOMATIC IRRIGATION: SENSORS AND SYSTEM This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investi gation by a candidate for the degree, Master of Science, and is accept able as meeting the thesis requirements for this degree, but without implying that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. �--- -"""'" _ _ -���--- - _ _ _ _____ -A>� - 7 7 T b � s/./ifjvisor ate Head, Electrical -r-oate Engineering Department ACKNOWLE GEMENTS The author wishes to express his sincere appreciation to Dr. A. J. Kurtenbach for his patient guidance and helpful suggestions, and to the Water Resources Institute for their support of this research. -

Electricity and Magnetism

Lecture 10 Fundamentals of Physics Phys 120, Fall 2015 Electricity and Magnetism A. J. Wagner North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58102 Fargo, September 24, 2015 Overview • Unexplained phenomena • Charges and electric forces revealed • Currents and circuits • Electricity and Magnetism are related! 1 Newton’s dream I wish we could derive the rest of the phenomena of Nature by the same kind of reasoning from mechanical principles, for I am induced by many reasons to suspect that they may all depend upon certain forces by which the particles of bodies, by some cause hitherto unknown, are either mutually impelled towards one another, and cohere in regular figures, or are repelled and recede from one another. from the preface of Newton’s Principia 2 What were those mysterious phenomena? 900 BC: Magnus, a Greek shepherd, walks across a field of black stones which pull the iron nails out of his sandals and the iron tip from his shepherd’s staff (authenticity not guaranteed). This region becomes known as Magnesia. 600 BC: Thales of Miletos(Greece) discovered that by rubbing an ’elektron’ (a hard, fossilized resin that today is known as amber) against a fur cloth, it would attract particles of straw and feathers. This strange effect remained a mystery for over 2000 years. 1269 AD: Petrus Peregrinus of Picardy, Italy, discovers that natural spherical magnets (lodestones) align needles with lines of longitude pointing between two pole positions on the stone. 3 ca. 1600: Dr.William Gilbert (court physician to Queen Elizabeth) discovers that the earth is a giant magnet just like one of the stones of Peregrinus, explaining how compasses work. -

Physics and Technology System of Units for Electrodynamics

PHYSICS AND TECHNOLOGY SYSTEM OF UNITS FOR ELECTRODYNAMICS∗ M. G. Ivanov† Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology Dolgoprudny, Russia Abstract The contemporary practice is to favor the use of the SI units for electric circuits and the Gaussian CGS system for electromagnetic field. A modification of the Gaussian system of units (the Physics and Technology System) is suggested. In the Physics and Technology System the units of measurement for electrical circuits coincide with SI units, and the equations for the electromagnetic field are almost the same form as in the Gaussian system. The XXIV CGMP (2011) Resolution ¾On the possible future revision of the International System of Units, the SI¿ provides a chance to initiate gradual introduction of the Physics and Technology System as a new modification of the SI. Keywords: SI, International System of Units, electrodynamics, Physics and Technology System of units, special relativity. 1. Introduction. One and a half century dispute The problem of choice of units for electrodynamics dates back to the time of M. Faraday (1822–1831) and J. Maxwell (1861–1873). Electrodynamics acquired its final form only after geometrization of special relativity by H. Minkowski (1907–1909). The improvement of contemporary (4-dimentional relativistic covariant) formulation of electrodynamics and its implementation in practice of higher education stretched not less than a half of century. Overview of some systems of units, which are used in electrodynamics could be found, for example, in books [2, 3] and paper [4]. Legislation and standards of many countries recommend to use in science and education The International System of Units (SI). -

CAR-ANS PART 05 Issue No. 2 Units of Measurement to Be Used In

CIVIL AVIATION REGULATIONS AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES Part 5 Governing UNITS OF MEASUREMENT TO BE USED IN AIR AND GROUND OPERATIONS CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY OF THE PHILIPPINES Old MIA Road, Pasay City1301 Metro Manila INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK CAR-ANS PART 5 Republic of the Philippines CIVIL AVIATION REGULATIONS AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES (CAR-ANS) Part 5 UNITS OF MEASUREMENTS TO BE USED IN AIR AND GROUND OPERATIONS 22 APRIL 2016 EFFECTIVITY Part 5 of the Civil Aviation Regulations-Air Navigation Services are issued under the authority of Republic Act 9497 and shall take effect upon approval of the Board of Directors of the CAAP. APPROVED BY: LT GEN WILLIAM K HOTCHKISS III AFP (RET) DATE Director General Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines Issue 2 15-i 16 May 2016 CAR-ANS PART 5 FOREWORD This Civil Aviation Regulations-Air Navigation Services (CAR-ANS) Part 5 was formulated and issued by the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines (CAAP), prescribing the standards and recommended practices for units of measurements to be used in air and ground operations within the territory of the Republic of the Philippines. This Civil Aviation Regulations-Air Navigation Services (CAR-ANS) Part 5 was developed based on the Standards and Recommended Practices prescribed by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) as contained in Annex 5 which was first adopted by the council on 16 April 1948 pursuant to the provisions of Article 37 of the Convention of International Civil Aviation (Chicago 1944), and consequently became applicable on 1 January 1949. The provisions contained herein are issued by authority of the Director General of the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines and will be complied with by all concerned. -

Magnetic Immunity of the MRAM Devices

APPLICATION NOTE AN-MEM-003 Magnetic Immunity of the MRAM Devices Table 1: Cross Reference of Applicable Products Product Name Manufacturer Part Number SMD # Device Type Internal PIC# 16Mb MRAM Device UT8MR2M8 5962-12227 01 WP01 64Mb MRAM Device UT8MR8M8 5962-13207 01 MQ09 *PIC = Product Identification Code 1.0 Overview CAES Colorado Springs offers a 16Mb and 64Mb Non-Volatile Magnetoresistive Random Access Memory (MRAM) device. The MRAM devices are designed specifically for operation in both HiRel and Space environments. This application note addresses concerns with the magnetic immunity of these devices. CAES has determined that the MRAM devices have no magnetic risk in the space environment and recommends proper handling to address terrestrial environments. 2.0 Magnetic Fields All magnetic fields are caused by electrical charge in motion. Even the fields from a stationary permanent magnet RELEASED RELEASED are the result of the rotation (quantum spin) of electrons within the material. There are two "components" of a magnetic field which are both commonly called "magnetic field." They are the B field (historically called Magnetic Induction) and the H field (historically called Magnetic Field). They are related by the equation B = H + 4pM where M is a term called "Magnetization" or "Magnetic Polarization" and is a property of the materials through which the 11 fields pass. Technically, M is the magnetic moment of the material per unit volume. To obtain the total B field, if considering the field in a volume of space, the free (unbound field) H plus the bound fields (magnetic dipoles) M / 13 must be known. -

Magnetic Units

Magnetic Units Magnetic poles, moments and magnetic dipoles The famous inverse square force law between two poles p1 and p2 separated by a distance r was discovered by the English scientist John Michell (1750), and the French scientist Charles Coulomb (1785): In the cgs (electromagnetic) system, k = 1, and the interaction force between two poles each of unit strength (in emu) separated by 1 cm is equal to 1 dyne. Alternatively, one can visualize this force as an interaction force between the pole p0 and the field H produced by another other pole of strength p: Therefore, the field produced by p at the location of p0 a distance r away is given by: The unit of the magnetic field, the Oersted (Oe), is defined as the strength of the field produced by a unit pole at a point 1 cm away (by eq. 3). Alternatively, it is the strength of the field which exerts a force of 1 dyne of a unit pole (by eq. 2). Faraday’s representation Michael Faraday represented the field strength in terms of “lines of force” (1 line of force = 1 maxwell (= 1 Mx)). In this representation, the field strength is defined as the number of lines of force passing through a unit area normal to the field. Therefore: 1 Oe = 1 line of force/cm2 = 1 Mx/cm2 (4) A bar magnet has a magnetic moment given in terms of the pole strength and length of the magnet by: The unit of the magnetic moment in cgs system is emu = erg/Oe. It is worth mentioning that the magnetic pole does not exist, neither can the distance between the two poles be determined accurately due to non-localization of the pole.