SI and CGS Units in Electromagnetism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix A: Symbols and Prefixes

Appendix A: Symbols and Prefixes (Appendix A last revised November 2020) This appendix of the Author's Kit provides recommendations on prefixes, unit symbols and abbreviations, and factors for conversion into units of the International System. Prefixes Recommended prefixes indicating decimal multiples or submultiples of units and their symbols are as follows: Multiple Prefix Abbreviation 1024 yotta Y 1021 zetta Z 1018 exa E 1015 peta P 1012 tera T 109 giga G 106 mega M 103 kilo k 102 hecto h 10 deka da 10-1 deci d 10-2 centi c 10-3 milli m 10-6 micro μ 10-9 nano n 10-12 pico p 10-15 femto f 10-18 atto a 10-21 zepto z 10-24 yocto y Avoid using compound prefixes, such as micromicro for pico and kilomega for giga. The abbreviation of a prefix is considered to be combined with the abbreviation/symbol to which it is directly attached, forming with it a new unit symbol, which can be raised to a positive or negative power and which can be combined with other unit abbreviations/symbols to form abbreviations/symbols for compound units. For example: 1 cm3 = (10-2 m)3 = 10-6 m3 1 μs-1 = (10-6 s)-1 = 106 s-1 1 mm2/s = (10-3 m)2/s = 10-6 m2/s Abbreviations and Symbols Whenever possible, avoid using abbreviations and symbols in paragraph text; however, when it is deemed necessary to use such, define all but the most common at first use. The following is a recommended list of abbreviations/symbols for some important units. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Measuring in Metric Units BEFORE Now WHY? You Used Metric Units

Measuring in Metric Units BEFORE Now WHY? You used metric units. You’ll measure and estimate So you can estimate the mass using metric units. of a bike, as in Ex. 20. Themetric system is a decimal system of measurement. The metric Word Watch system has units for length, mass, and capacity. metric system, p. 80 Length Themeter (m) is the basic unit of length in the metric system. length: meter, millimeter, centimeter, kilometer, Three other metric units of length are themillimeter (mm) , p. 80 centimeter (cm) , andkilometer (km) . mass: gram, milligram, kilogram, p. 81 You can use the following benchmarks to estimate length. capacity: liter, milliliter, kiloliter, p. 82 1 millimeter 1 centimeter 1 meter thickness of width of a large height of the a dime paper clip back of a chair 1 kilometer combined length of 9 football fields EXAMPLE 1 Using Metric Units of Length Estimate the length of the bandage by imagining paper clips laid next to it. Then measure the bandage with a metric ruler to check your estimate. 1 Estimate using paper clips. About 5 large paper clips fit next to the bandage, so it is about 5 centimeters long. ch O at ut! W 2 Measure using a ruler. A typical metric ruler allows you to measure Each centimeter is divided only to the nearest tenth of into tenths, so the bandage cm 12345 a centimeter. is 4.8 centimeters long. 80 Chapter 2 Decimal Operations Mass Mass is the amount of matter that an object has. The gram (g) is the basic metric unit of mass. -

S.I. and Cgs Units

Some Notes on SI vs. cgs Units by Jason Harlow Last updated Feb. 8, 2011 by Jason Harlow. Introduction Within “The Metric System”, there are actually two separate self-consistent systems. One is the Systme International or SI system, which uses Metres, Kilograms and Seconds for length, mass and time. For this reason it is sometimes called the MKS system. The other system uses centimetres, grams and seconds for length, mass and time. It is most often called the cgs system, and sometimes it is called the Gaussian system or the electrostatic system. Each system has its own set of derived units for force, energy, electric current, etc. Surprisingly, there are important differences in the basic equations of electrodynamics depending on which system you are using! Important textbooks such as Classical Electrodynamics 3e by J.D. Jackson ©1998 by Wiley and Classical Electrodynamics 2e by Hans C. Ohanian ©2006 by Jones & Bartlett use the cgs system in all their presentation and derivations of basic electric and magnetic equations. I think many theorists prefer this system because the equations look “cleaner”. Introduction to Electrodynamics 3e by David J. Griffiths ©1999 by Benjamin Cummings uses the SI system. Here are some examples of units you may encounter, the relevant facts about them, and how they relate to the SI and cgs systems: Force The SI unit for force comes from Newton’s 2nd law, F = ma, and is the Newton or N. 1 N = 1 kg·m/s2. The cgs unit for force comes from the same equation and is called the dyne, or dyn. -

Metric System.Pdf

METRIC SYSTEM THE METRIC SYSTEM The metric system is much easier. All metric units are related by factors of 10. Nearly the entire world (95%), except the United States, now uses the metric system. Metric is used exclusively in science. Because the metric system uses units related by factors of ten and the types of units (distance, area, volume, mass) are simply-related, performing calculations with the metric system is much easier. METRIC CHART Prefix Symbol Factor Number Factor Word Kilo K 1,000 Thousand Hecto H 100 Hundred Deca Dk 10 Ten Base Unit Meter, gram, liter 1 One Deci D 0.1 Tenth Centi C 0.01 Hundredth Milli M 0.001 Thousandth The metric system has three units or bases. Meter – the basic unit used to measure length Gram – the basic unit used to measure weight Liter – the basic unit used to measure liquid capacity (think 2 Liter cokes!) The United States, Liberia and Burma (countries in black) have stuck with using the Imperial System of measurement. You can think of “the metric system” as a nickname for the International System of Units, or SI. HOW TO REMEMBER THE PREFIXES Kids Kilo Have Hecto Dropped Deca Over base unit (gram, liter, meter) Dead Deci Converting Centi Metrics Milli Large Units – Kilo (1000), Hecto (100), Deca (10) Small Units – Deci (0.1), Centi (0.01), Milli (0.001) Because you are dealing with multiples of ten, you do not have to calculate anything. All you have to do is move the decimal point, but you need to understand what you are doing when you move the decimal point. -

DIMENSIONS and UNITS to Get the Value of a Quantity in Gaussian Units, Multiply the Value Ex- Pressed in SI Units by the Conversion Factor

DIMENSIONS AND UNITS To get the value of a quantity in Gaussian units, multiply the value ex- pressed in SI units by the conversion factor. Multiples of 3 intheconversion factors result from approximating the speed of light c =2.9979 1010 cm/sec × 3 1010 cm/sec. ≈ × Dimensions Physical Sym- SI Conversion Gaussian Quantity bol SI Gaussian Units Factor Units t2q2 Capacitance C l farad 9 1011 cm ml2 × m1/2l3/2 Charge q q coulomb 3 109 statcoulomb t × q m1/2 Charge ρ coulomb 3 103 statcoulomb 3 3/2 density l l t /m3 × /cm3 tq2 l Conductance siemens 9 1011 cm/sec ml2 t × 2 tq 1 9 1 Conductivity σ siemens 9 10 sec− 3 ml t /m × q m1/2l3/2 Current I,i ampere 3 109 statampere t t2 × q m1/2 Current J, j ampere 3 105 statampere 2 1/2 2 density l t l t /m2 × /cm2 m m 3 3 3 Density ρ kg/m 10− g/cm l3 l3 q m1/2 Displacement D coulomb 12π 105 statcoulomb l2 l1/2t /m2 × /cm2 1/2 ml m 1 4 Electric field E volt/m 10− statvolt/cm t2q l1/2t 3 × 2 1/2 1/2 ml m l 1 2 Electro- , volt 10− statvolt 2 motance EmfE t q t 3 × ml2 ml2 Energy U, W joule 107 erg t2 t2 m m Energy w, ϵ joule/m3 10 erg/cm3 2 2 density lt lt 10 Dimensions Physical Sym- SI Conversion Gaussian Quantity bol SI Gaussian Units Factor Units ml ml Force F newton 105 dyne t2 t2 1 1 Frequency f, ν hertz 1 hertz t t 2 ml t 1 11 Impedance Z ohm 10− sec/cm tq2 l 9 × 2 2 ml t 1 11 2 Inductance L henry 10− sec /cm q2 l 9 × Length l l l meter (m) 102 centimeter (cm) 1/2 q m 3 Magnetic H ampere– 4π 10− oersted 1/2 intensity lt l t turn/m × ml2 m1/2l3/2 Magnetic flux Φ weber 108 maxwell tq t m m1/2 Magnetic -

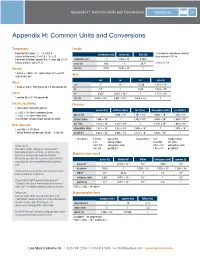

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215 Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Temperature Length Fahrenheit to Celsius: °C = (°F-32)/1.8 1 micrometer (sometimes referred centimeter (cm) meter (m) inch (in) Celsius to Fahrenheit: °F = (1.8 × °C) + 32 to as micron) = 10-6 m Fahrenheit to Kelvin: convert °F to °C, then add 273.15 centimeter (cm) 1 1.000 × 10–2 0.3937 -3 Celsius to Kelvin: add 273.15 meter (m) 100 1 39.37 1 mil = 10 in Volume inch (in) 2.540 2.540 × 10–2 1 –3 3 1 liter (l) = 1.000 × 10 cubic meters (m ) = 61.02 Area cubic inches (in3) cm2 m2 in2 circ mil Mass cm2 1 10–4 0.1550 1.974 × 105 1 kilogram (kg) = 1000 grams (g) = 2.205 pounds (lb) m2 104 1 1550 1.974 × 109 Force in2 6.452 6.452 × 10–4 1 1.273 × 106 1 newton (N) = 0.2248 pounds (lb) circ mil 5.067 × 10–6 5.067 × 10–10 7.854 × 10–7 1 Electric resistivity Pressure 1 micro-ohm-centimeter (µΩ·cm) pascal (Pa) millibar (mbar) torr (Torr) atmosphere (atm) psi (lbf/in2) = 1.000 × 10–6 ohm-centimeter (Ω·cm) –2 –3 –6 –4 = 1.000 × 10–8 ohm-meter (Ω·m) pascal (Pa) 1 1.000 × 10 7.501 × 10 9.868 × 10 1.450 × 10 = 6.015 ohm-circular mil per foot (Ω·circ mil/ft) millibar (mbar) 1.000 × 102 1 7.502 × 10–1 9.868 × 10–4 1.450 × 10–2 2 0 –3 –2 Heat flow rate torr (Torr) 1.333 × 10 1.333 × 10 1 1.316 × 10 1.934 × 10 5 3 2 1 1 watt (W) = 3.413 Btu/h atmosphere (atm) 1.013 × 10 1.013 × 10 7.600 × 10 1 1.470 × 10 1 British thermal unit per hour (Btu/h) = 0.2930 W psi (lbf/in2) 6.897 × 103 6.895 × 101 5.172 × 101 6.850 × 10–2 1 1 torr (Torr) = 133.332 pascal (Pa) 1 pascal (Pa) = 0.01 millibar (mbar) 1.33 millibar (mbar) 0.007501 torr (Torr) –6 A Note on SI 0.001316 atmosphere (atm) 9.87 × 10 atmosphere (atm) 2 –4 2 The values in this catalog are expressed in 0.01934 psi (lbf/in ) 1.45 × 10 psi (lbf/in ) International System of Units, or SI (from the Magnetic induction B French Le Système International d’Unités). -

Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 151. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/151 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 30 Magnetic Fields of Currents 30-1 Magnetic Field around an Electric Current The first evidence for the existence of a magnetic field around an electric current was observed in 1820 by Hans Christian Oersted (1777-1851). He found that a wire carrying current caused a freely pivoted compass needle B D N rDirection I of current D II. • ~ I I In wire ' \ N I I c , I s c (a) (b) Fig. 30-1 Oersted's experiment. Compass needle is deflected toward the west when the wire CD carrying current is placed above it and the direction of the current is toward the north, from C to D. in its vicinity to be deflected. If the current in a long straight wire is directed from C to D, as shown in Figure 30-1, a compass needle below it, whose initial orientation is shown in dotted lines, will have its north pole deflected to the left and its south pole deflected to the right. -

20 Coulomb's Law Of

Coulomb’s Law of 20 Electrostatic Forces Charge Interactions Are Described by Coulomb’s Law Electrical interactions between charges govern much of physics, chemistry, and biology. They are the basis for chemical bonding, weak and strong. Salts dis- solve in water to form the solutions of charged ions that cover three-quarters of the Earth’s surface. Salt water forms the working fluid of living cells. pH and salts regulate the associations of proteins, DNA, cells, and colloids, and the conformations of biopolymers. Nervous systems would not function without ion fluxes. Electrostatic interactions are also important in batteries, corrosion, and electroplating. Charge interactions obey Coulomb’s law. When more than two charged par- ticles interact, the energies are sums of Coulombic interactions. To calculate such sums, we introduce the concepts of the electric field, Gauss’s law, and the electrostatic potential. With these tools, you can determine the electrostatic force exerted by one charged object on another, as when an ion interacts with a protein, DNA molecule, or membrane, or when a charged polymer changes conformation. Coulomb’s law was discovered in careful experiments by H Cavendish (1731–1810), J Priestley (1733–1804), and CA Coulomb (1736–1806) on macro- scopic objects such as magnets, glass rods, charged spheres, and silk cloths. Coulomb’s law applies to a wide range of size scales, including atoms, molecules, and biological cells. It states that the interaction energy u(r ) 385 between two charges in a vacuum is Cq q u(r ) = 1 2 , (20.1) r where q1 and q2 are the magnitudes of the two charges, r is the distance sep- arating them, and C = 1/4πε0 is a proportionality constant (see box below). -

Manual of Style

Manual Of Style 1 MANUAL OF STYLE TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS ...............3 101.0 Scope .............................................. 3 102.0 Codes and Standards..................... 3 103.0 Code Division.................................. 3 104.0 Table of Contents ........................... 4 CHAPTER 2 ADMINISTRATION .........................6 201.0 Administration ................................. 6 202.0 Chapter 2 Definitions ...................... 6 203.0 Referenced Standards Table ......... 6 204.0 Individual Chapter Administrative Text ......................... 6 205.0 Appendices ..................................... 7 206.0 Installation Standards ..................... 7 207.0 Extract Guidelines .......................... 7 208.0 Index ............................................... 9 CHAPTER 3 TECHNICAL STYLE .................... 10 301.0 Technical Style ............................. 10 302.0 Technical Rules ............................ 10 Table 302.3 Possible Unenforceable and Vague Terms ................................ 10 303.0 Health and Safety ........................ 11 304.0 Rules for Mandatory Documents .................................... 11 305.0 Writing Mandatory Requirements ............................... 12 Table 305.0 Typical Mandatory Terms............. 12 CHAPTER 4 EDITORIAL STYLE ..................... 14 401.0 Editorial Style ................................ 14 402.0 Definitions ...................................... 14 403.0 Units of Measure ............................ 15 404.0 Punctuation -

Introduction to Electrostatics

Introduction to Electrostatics Charles Augustin de Coulomb (1736 - 1806) December 23, 2000 Contents 1 Coulomb's Law 2 2 Electric Field 4 3 Gauss's Law 7 4 Di®erential Form of Gauss's Law 9 5 An Equation for E; the Scalar Potential 10 r £ 5.1 Conservative Potentials . 11 6 Poisson's and Laplace's Equations 13 7 Energy in the Electric Field; Capacitance; Forces 15 7.1 Conductors . 20 7.2 Forces on Charged Conductors . 22 1 8 Green's Theorem 27 8.1 Green's Theorem . 29 8.2 Applying Green's Theorem 1 . 30 8.3 Applying Green's Theorem 2 . 31 8.3.1 Greens Theorem with Dirichlet B.C. 34 8.3.2 Greens Theorem with Neumann B.C. 36 2 We shall follow the approach of Jackson, which is more or less his- torical. Thus we start with classical electrostatics, pass on to magneto- statics, add time dependence, and wind up with Maxwell's equations. These are then expressed within the framework of special relativity. The remainder of the course is devoted to a broad range of interesting and important applications. This development may be contrasted with the more formal and el- egant approach which starts from the Maxwell equations plus special relativity and then proceeds to work out electrostatics and magneto- statics - as well as everything else - as special cases. This is the method of e.g., Landau and Lifshitz, The Classical Theory of Fields. The ¯rst third of the course, i.e., Physics 707, deals with physics which should be familiar to everyone; what will perhaps not be familiar are the mathematical techniques and functions that will be introduced in order to solve certain kinds of problems. -

Physics and Technology System of Units for Electrodynamics

PHYSICS AND TECHNOLOGY SYSTEM OF UNITS FOR ELECTRODYNAMICS∗ M. G. Ivanov† Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology Dolgoprudny, Russia Abstract The contemporary practice is to favor the use of the SI units for electric circuits and the Gaussian CGS system for electromagnetic field. A modification of the Gaussian system of units (the Physics and Technology System) is suggested. In the Physics and Technology System the units of measurement for electrical circuits coincide with SI units, and the equations for the electromagnetic field are almost the same form as in the Gaussian system. The XXIV CGMP (2011) Resolution ¾On the possible future revision of the International System of Units, the SI¿ provides a chance to initiate gradual introduction of the Physics and Technology System as a new modification of the SI. Keywords: SI, International System of Units, electrodynamics, Physics and Technology System of units, special relativity. 1. Introduction. One and a half century dispute The problem of choice of units for electrodynamics dates back to the time of M. Faraday (1822–1831) and J. Maxwell (1861–1873). Electrodynamics acquired its final form only after geometrization of special relativity by H. Minkowski (1907–1909). The improvement of contemporary (4-dimentional relativistic covariant) formulation of electrodynamics and its implementation in practice of higher education stretched not less than a half of century. Overview of some systems of units, which are used in electrodynamics could be found, for example, in books [2, 3] and paper [4]. Legislation and standards of many countries recommend to use in science and education The International System of Units (SI).