The Concept of Field in the History of Electromagnetism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implementation of the Fizeau Aether Drag Experiment for An

Implementation of the Fizeau Aether Drag Experiment for an Undergraduate Physics Laboratory by Bahrudin Trbalic Submitted to the Department of Physics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Physics at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May 2020 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2020. All rights reserved. ○ Author................................................................ Department of Physics May 8, 2020 Certified by. Sean P. Robinson Lecturer of Physics Thesis Supervisor Certified by. Joseph A. Formaggio Professor of Physics Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . Nergis Mavalvala Associate Department Head, Department of Physics 2 Implementation of the Fizeau Aether Drag Experiment for an Undergraduate Physics Laboratory by Bahrudin Trbalic Submitted to the Department of Physics on May 8, 2020, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Physics Abstract This work presents the description and implementation of the historically significant Fizeau aether drag experiment in an undergraduate physics laboratory setting. The implementation is optimized to be inexpensive and reproducible in laboratories that aim to educate students in experimental physics. A detailed list of materials, experi- mental setup, and procedures is given. Additionally, a laboratory manual, preparatory materials, and solutions are included. Thesis Supervisor: Sean P. Robinson Title: Lecturer of Physics Thesis Supervisor: Joseph A. Formaggio Title: Professor of Physics 3 4 Acknowledgments I gratefully acknowledge the instrumental help of Prof. Joseph Formaggio and Dr. Sean P. Robinson for the guidance in this thesis work and in my academic life. The Experimental Physics Lab (J-Lab) has been the pinnacle of my MIT experience and I’m thankful for the time spent there. -

Simple Circuit Theory and the Solution of Two Electricity Problems from The

Simple circuit theory and the solution of two electricity problems from the Victorian Age A C Tort ∗ Departamento de F´ısica Te´orica - Instituto de F´ısica Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Caixa Postal 68.528; CEP 21941-972 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil May 22, 2018 Abstract Two problems from the Victorian Age, the subdivision of light and the determination of the leakage point in an undersea telegraphic cable are discussed and suggested as a concrete illustrations of the relationships between textbook physics and the real world. Ohm’s law and simple algebra are the only tools we need to discuss them in the classroom. arXiv:0811.0954v1 [physics.pop-ph] 6 Nov 2008 ∗e-mail: [email protected]. 1 1 Introduction Some time ago, the present author had the opportunity of reading Paul J. Nahin’s [1] fascinating biog- raphy of the Victorian physicist and electrician Oliver Heaviside (1850-1925). Heaviside’s scientific life unrolls against a background of theoretical and technical challenges that the scientific and technological developments fostered by the Industrial Revolution presented to engineers and physicists of those times. It is a time where electromagnetic theory as formulated by James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879) was un- derstood by only a small group of men, Lodge, FitzGerald and Heaviside, among others, that had the mathematical sophistication and imagination to grasp the meaning and take part in the great Maxwellian synthesis. Almost all of the electrical engineers, or electricians as they were called at the time, considered themselves as “practical men”, which effectively meant that most of them had a working knowledge of the electromagnetic phenomena spiced up with bits of electrical theory, to wit, Ohm’s law and the Joule effect. -

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1. A. Pre-1820. (1) Electrostatics (frictional electricity) • 1780s. Coulomb's description: ! Two electric fluids: positive and negative. ! Inverse square law: It follows therefore from these three tests, that the repulsive force that the two balls -- [which were] electrified with the same kind of electricity -- exert on each other, Charles-Augustin de Coulomb follows the inverse proportion of (1736-1806) the square of the distance."" (2) Magnetism: Coulomb's description: • Two fluids ("astral" and "boreal") obeying inverse square law. • No magnetic monopoles: fluids are imprisoned in molecules of magnetic bodies. (3) Galvanism • 1770s. Galvani's frog legs. "Animal electricity": phenomenon belongs to biology. • 1800. Volta's ("volatic") pile. Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) • Pile consists of alternating copper and • Charged rod connected zinc plates separated by to inner foil. brine-soaked cloth. • Outer foil grounded. • A "battery" of Leyden • Inner and outer jars that can surfaces store equal spontaeously recharge but opposite charges. themselves. 1745 Leyden jar. • Volta: Pile is an electric phenomenon and belongs to physics. • But: Nicholson and Carlisle use voltaic current to decompose Alessandro Volta water into hydrogen and oxygen. Pile belongs to chemistry! (1745-1827) • Are electricity and magnetism different phenomena? ! Electricity involves violent actions and effects: sparks, thunder, etc. ! Magnetism is more quiet... Hans Christian • 1820. Oersted's Experimenta circa effectum conflictus elecrici in Oersted (1777-1851) acum magneticam ("Experiments on the effect of an electric conflict on the magnetic needle"). ! Galvanic current = an "electric conflict" between decompositions and recompositions of positive and negative electricities. ! Experiments with a galvanic source, connecting wire, and rotating magnetic needle: Needle moves in presence of pile! "Otherwise one could not understand how Oersted's Claims the same portion of the wire drives the • Electric conflict acts on magnetic poles. -

Faraday's Law Da

Faraday's Law dA B B r r Φ≡B •d A B ∫ dΦ ε= − B dt Faraday’s Law of Induction r r Recall the definition of magnetic flux is ΦB =B∫ ⋅ d A Faraday’s Law is the induced EMF in a closed loop equal the negative of the time derivative of magnetic flux change in the loop, d r r dΦ ε= −B∫ d ⋅= A − B dt dt Constant B field, changing B field, no induced EMF causes induced EMF in loop in loop Getting the sign EMF in Faraday’s Law of Induction Define the loop and an area vector, A, who magnitude is the Area and whose direction normal to the surface. A The choice of vector A direction defines the direction of EMF with a right hand rule. Your thumb in A direction and then your fingers point to positive EMF direction. Lenz’s Law – easier way! The direction of any magnetic induction effect is such as to oppose the cause of the effect. ⇒ Convenient method to determine I direction Heinrich Friedrich Example if an external magnetic field on a loop Emil Lenz is increasing, the induced current creates a field opposite that reduces the net field. (1804-1865) Example if an external magnetic field on a loop is decreasing, the induced current creates a field parallel to the that tends to increase the net field. Incredible shrinking loop: a circular loop of wire with a magnetic flux is shrinking with time. In which direction is the induced current? (a) There is none. (b) CW. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Speed Limit: How the Search for an Absolute Frame of Reference in the Universe Led to Einstein’S Equation E =Mc2 — a History of Measurements of the Speed of Light

Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, vol. 152, part 2, 2019, pp. 216–241. ISSN 0035-9173/19/020216-26 Speed limit: how the search for an absolute frame of reference in the Universe led to Einstein’s equation 2 E =mc — a history of measurements of the speed of light John C. H. Spence ForMemRS Department of Physics, Arizona State University, Tempe AZ, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article describes one of the greatest intellectual adventures in the history of mankind — the history of measurements of the speed of light and their interpretation (Spence 2019). This led to Einstein’s theory of relativity in 1905 and its most important consequence, the idea that matter is a form of energy. His equation E=mc2 describes the energy release in the nuclear reactions which power our sun, the stars, nuclear weapons and nuclear power stations. The article is about the extraordinarily improbable connection between the search for an absolute frame of reference in the Universe (the Aether, against which to measure the speed of light), and Einstein’s most famous equation. Introduction fixed speed with respect to the Aether frame n 1900, the field of physics was in turmoil. of reference. If we consider waves running IDespite the triumphs of Newton’s laws of along a river in which there is a current, it mechanics, despite Maxwell’s great equations was understood that the waves “pick up” the leading to the discovery of radio and Boltz- speed of the current. But Michelson in 1887 mann’s work on the foundations of statistical could find no effect of the passing Aether mechanics, Lord Kelvin’s talk1 at the Royal wind on his very accurate measurements Institution in London on Friday, April 27th of the speed of light, no matter in which 1900, was titled “Nineteenth-century clouds direction he measured it, with headwind or over the dynamical theory of heat and light.” tailwind. -

Faraday's Law Da

Faraday's Law dA B B r r Φ≡B •d A B ∫ dΦ ε= − B dt Applications of Magnetic Induction • AC Generator – Water turns wheel Æ rotates magnet Æ changes flux Æ induces emf Æ drives current • “Dynamic” Microphones (E.g., some telephones) – Sound Æ oscillating pressure waves Æ oscillating [diaphragm + coil] Æ oscillating magnetic flux Æ oscillating induced emf Æ oscillating current in wire Question: Do dynamic microphones need a battery? More Applications of Magnetic Induction • Tape / Hard Drive / ZIP Readout – Tiny coil responds to change in flux as the magnetic domains (encoding 0’s or 1’s) go by. 2007 Nobel Prize!!!!!!!! Giant Magnetoresistance • Credit Card Reader – Must swipe card Æ generates changing flux – Faster swipe Æ bigger signal More Applications of Magnetic Induction • Magnetic Levitation (Maglev) Trains – Induced surface (“eddy”) currents produce field in opposite direction Æ Repels magnet Æ Levitates train S N rails “eddy” current – Maglev trains today can travel up to 310 mph Æ Twice the speed of Amtrak’s fastest conventional train! – May eventually use superconducting loops to produce B-field Æ No power dissipation in resistance of wires! Faraday’s Law of Induction r r Recall the definition of magnetic flux is ΦB =B∫ ⋅ d A Faraday’s Law is the induced EMF in a closed loop equal the negative of the time derivative of magnetic flux change in the loop, d r r dΦ ε= −B∫ d ⋅= A − B dt dt Constant B field, changing B field, no induced EMF causes induced EMF in loop in loop Getting the sign EMF in Faraday’s Law of Induction Define the loop and an area vector, A, who magnitude is the Area and whose direction normal to the surface. -

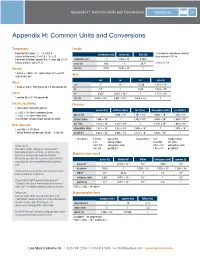

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215 Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Temperature Length Fahrenheit to Celsius: °C = (°F-32)/1.8 1 micrometer (sometimes referred centimeter (cm) meter (m) inch (in) Celsius to Fahrenheit: °F = (1.8 × °C) + 32 to as micron) = 10-6 m Fahrenheit to Kelvin: convert °F to °C, then add 273.15 centimeter (cm) 1 1.000 × 10–2 0.3937 -3 Celsius to Kelvin: add 273.15 meter (m) 100 1 39.37 1 mil = 10 in Volume inch (in) 2.540 2.540 × 10–2 1 –3 3 1 liter (l) = 1.000 × 10 cubic meters (m ) = 61.02 Area cubic inches (in3) cm2 m2 in2 circ mil Mass cm2 1 10–4 0.1550 1.974 × 105 1 kilogram (kg) = 1000 grams (g) = 2.205 pounds (lb) m2 104 1 1550 1.974 × 109 Force in2 6.452 6.452 × 10–4 1 1.273 × 106 1 newton (N) = 0.2248 pounds (lb) circ mil 5.067 × 10–6 5.067 × 10–10 7.854 × 10–7 1 Electric resistivity Pressure 1 micro-ohm-centimeter (µΩ·cm) pascal (Pa) millibar (mbar) torr (Torr) atmosphere (atm) psi (lbf/in2) = 1.000 × 10–6 ohm-centimeter (Ω·cm) –2 –3 –6 –4 = 1.000 × 10–8 ohm-meter (Ω·m) pascal (Pa) 1 1.000 × 10 7.501 × 10 9.868 × 10 1.450 × 10 = 6.015 ohm-circular mil per foot (Ω·circ mil/ft) millibar (mbar) 1.000 × 102 1 7.502 × 10–1 9.868 × 10–4 1.450 × 10–2 2 0 –3 –2 Heat flow rate torr (Torr) 1.333 × 10 1.333 × 10 1 1.316 × 10 1.934 × 10 5 3 2 1 1 watt (W) = 3.413 Btu/h atmosphere (atm) 1.013 × 10 1.013 × 10 7.600 × 10 1 1.470 × 10 1 British thermal unit per hour (Btu/h) = 0.2930 W psi (lbf/in2) 6.897 × 103 6.895 × 101 5.172 × 101 6.850 × 10–2 1 1 torr (Torr) = 133.332 pascal (Pa) 1 pascal (Pa) = 0.01 millibar (mbar) 1.33 millibar (mbar) 0.007501 torr (Torr) –6 A Note on SI 0.001316 atmosphere (atm) 9.87 × 10 atmosphere (atm) 2 –4 2 The values in this catalog are expressed in 0.01934 psi (lbf/in ) 1.45 × 10 psi (lbf/in ) International System of Units, or SI (from the Magnetic induction B French Le Système International d’Unités). -

Apparatus Named After Our Academic Ancestors, III

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange Faculty Publications Physics 2014 Apparatus Named After Our Academic Ancestors, III Tom Greenslade Kenyon College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/physics_publications Part of the Physics Commons Recommended Citation “Apparatus Named After Our Academic Ancestors III”, The Physics Teacher, 52, 360-363 (2014) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Physics at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Apparatus Named After Our Academic Ancestors, III Thomas B. Greenslade Jr. Citation: The Physics Teacher 52, 360 (2014); doi: 10.1119/1.4893092 View online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.4893092 View Table of Contents: http://scitation.aip.org/content/aapt/journal/tpt/52/6?ver=pdfcov Published by the American Association of Physics Teachers Articles you may be interested in Crystal (Xal) radios for learning physics Phys. Teach. 53, 317 (2015); 10.1119/1.4917450 Apparatus Named After Our Academic Ancestors — II Phys. Teach. 49, 28 (2011); 10.1119/1.3527751 Apparatus Named After Our Academic Ancestors — I Phys. Teach. 48, 604 (2010); 10.1119/1.3517028 Physics Northwest: An Academic Alliance Phys. Teach. 45, 421 (2007); 10.1119/1.2783150 From Our Files Phys. Teach. 41, 123 (2003); 10.1119/1.1542054 This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AAPT content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. -

Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1970 Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System Herman G. Hamre Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Hamre, Herman G., "Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System" (1970). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3780. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/3780 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUTOMATIC IRRIGATION: SENSORS AND SYSTEM BY HERMAN G. HAMRE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science, Major in Electrical Engineering, South Dakota State University 1970 SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY AUTOMATIC IRRIGATION: SENSORS AND SYSTEM This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investi gation by a candidate for the degree, Master of Science, and is accept able as meeting the thesis requirements for this degree, but without implying that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. �--- -"""'" _ _ -���--- - _ _ _ _____ -A>� - 7 7 T b � s/./ifjvisor ate Head, Electrical -r-oate Engineering Department ACKNOWLE GEMENTS The author wishes to express his sincere appreciation to Dr. A. J. Kurtenbach for his patient guidance and helpful suggestions, and to the Water Resources Institute for their support of this research. -

Electricity and Magnetism

Lecture 10 Fundamentals of Physics Phys 120, Fall 2015 Electricity and Magnetism A. J. Wagner North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58102 Fargo, September 24, 2015 Overview • Unexplained phenomena • Charges and electric forces revealed • Currents and circuits • Electricity and Magnetism are related! 1 Newton’s dream I wish we could derive the rest of the phenomena of Nature by the same kind of reasoning from mechanical principles, for I am induced by many reasons to suspect that they may all depend upon certain forces by which the particles of bodies, by some cause hitherto unknown, are either mutually impelled towards one another, and cohere in regular figures, or are repelled and recede from one another. from the preface of Newton’s Principia 2 What were those mysterious phenomena? 900 BC: Magnus, a Greek shepherd, walks across a field of black stones which pull the iron nails out of his sandals and the iron tip from his shepherd’s staff (authenticity not guaranteed). This region becomes known as Magnesia. 600 BC: Thales of Miletos(Greece) discovered that by rubbing an ’elektron’ (a hard, fossilized resin that today is known as amber) against a fur cloth, it would attract particles of straw and feathers. This strange effect remained a mystery for over 2000 years. 1269 AD: Petrus Peregrinus of Picardy, Italy, discovers that natural spherical magnets (lodestones) align needles with lines of longitude pointing between two pole positions on the stone. 3 ca. 1600: Dr.William Gilbert (court physician to Queen Elizabeth) discovers that the earth is a giant magnet just like one of the stones of Peregrinus, explaining how compasses work. -

HISTORICAL SURVEY SOME PIONEERS of the APPLICATIONS of FRACTIONAL CALCULUS Duarte Valério 1, José Tenreiro Machado 2, Virginia

HISTORICAL SURVEY SOME PIONEERS OF THE APPLICATIONS OF FRACTIONAL CALCULUS Duarte Val´erio 1,Jos´e Tenreiro Machado 2, Virginia Kiryakova 3 Abstract In the last decades fractional calculus (FC) became an area of intensive research and development. This paper goes back and recalls important pio- neers that started to apply FC to scientific and engineering problems during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Those we present are, in alphabet- ical order: Niels Abel, Kenneth and Robert Cole, Andrew Gemant, Andrey N. Gerasimov, Oliver Heaviside, Paul L´evy, Rashid Sh. Nigmatullin, Yuri N. Rabotnov, George Scott Blair. MSC 2010 : Primary 26A33; Secondary 01A55, 01A60, 34A08 Key Words and Phrases: fractional calculus, applications, pioneers, Abel, Cole, Gemant, Gerasimov, Heaviside, L´evy, Nigmatullin, Rabotnov, Scott Blair 1. Introduction In 1695 Gottfried Leibniz asked Guillaume l’Hˆopital if the (integer) order of derivatives and integrals could be extended. Was it possible if the order was some irrational, fractional or complex number? “Dream commands life” and this idea motivated many mathematicians, physicists and engineers to develop the concept of fractional calculus (FC). Dur- ing four centuries many famous mathematicians contributed to the theo- retical development of FC. We can list (in alphabetical order) some im- portant researchers since 1695 (see details at [1, 2, 3], and posters at http://www.math.bas.bg/∼fcaa): c 2014 Diogenes Co., Sofia pp. 552–578 , DOI: 10.2478/s13540-014-0185-1 SOME PIONEERS OF THE APPLICATIONS . 553 • Abel, Niels Henrik (5 August 1802 - 6 April 1829), Norwegian math- ematician • Al-Bassam, M. A. (20th century), mathematician of Iraqi origin • Cole, Kenneth (1900 - 1984) and Robert (1914 - 1990), American physicists • Cossar, James (d.