What Did Paul Know About Jesus?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twenty Third Sunday in Ordinary Time September 5, 2021

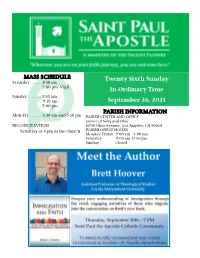

MASS SCHEDULE Twenty Sixth Sunday Saturday .......... 8:30 am 5:00 pm Vigil In Ordinary Time Sunday ............. 7:30 am 9:30 am September 26, 2021 5:00 pm PARISH INFORMATION Mon-Fri ............ 6:30 am and 5:30 pm PARISH CENTER AND OFFICE Corner of Selby and Ohio RECONCILIATION 10750 Ohio Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90024 Saturday at 4 pm in the church PARISH OFFICE HOURS Monday-Friday 9:00 am—4:00 pm Saturday 9:00 am-12:00 pm Sunday Closed Page 2 September 26, 2021 Dear Sisters and Brothers in Christ – The Annual Fall Festival is here! The theme is One Love, a response to the pandemic – one love that flows from God. Our Festival Team led by Wanda Ahmadi have taken every precaution in this time of COVID. To attend in person, full vaccination is strongly recommended and/or a COVID test within 72 hours of attending; masks are to be worn at all times except when eating or drinking; practice physical distancing; and, wash hands fre- quently. See you on the Ferris wheel! Our next faith formation program is a special presentation of a new book, “Immigration and Faith: Cultural, Biblical, and Theological Narratives” by professor of theology at Loyola Marymount University, Brett Hoo- ver on Thursday, September 30 at 7 PM in the Church. Brett utilizes vivid and engaging narratives of those who migrate to see migration through the lens of our faith. The book is available for purchase at the Parish Office and will be available at the presentation. You may attend online at St. -

St. Paul the Apostle1 by Kenneth John Paul Pomeisl2

St. Paul the Apostle1 by Kenneth John Paul Pomeisl2 St. Paul was born in the town of Tarsus in Cilicia which we today call Turkey around the year 3 A.D. His original name was actually Saul. He was a Pharisee which were a group of very devout Jews who were very serious about “the Law”. After Pentecost the Church, known then as “the Way”, slowly began to grow. As it did many of the Jews did not like this. They thought these newcomers were heretics. Saul was involved with putting these people in prison. He was at the execution of the first martyr, St. Stephen, who died by stoning. As he died St. Stephen asked God to forgive those who were killing him. Saul would continue to arrest every follower of the Way he could find. Some people believe that because of what St. Stephen did and how these people acted Saul started to have doubts about what he was doing but he would not change his mind. Then one day Saul was struck by a great light and blinded. As he was down here heard a voice asking “Saul, Saul, Why do you persecute me?” Saul asked this voice who he was and the reply was “I am Jesus, who you are persecuting”. After this Saul has his sight restored and becomes a Christian himself. After a while he is sent on missions to preach the Gospel to the Gentiles (non-Jews). St. Paul endures many hardships but creates many Churches and during this time writes many of his letters which we know today as Epistles in the New Testament. -

A:Cts of the Apostles (Revised Version)

THE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE EDITION. A:CTS OF THE APOSTLES (REVISED VERSION) (CHAPTERS I.-XVI.) WITH BY THK REV. F. MARSHALL, M.A., (Lau Ezhibition,r of St, John's College, Camb,idge)• Recto, of Mileham, formerly Principal of the Training College, Ca11narthffl. and la1ely Head- Master of Almondbury Grammar School, First Edition 1920. Ten Impressions to 1932. Jonb.on: GEORGE GILL & SONS, Ln., MINERVA HOUSE, PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.4. MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ACTS OPTBE APOSTLES . <t. ~ -li .i- C-4 l y .A. lO 15 20 PREFACE. 'i ms ~amon of the first Sixteen Chapters of the Acts of the Apostles is intended for the use of Students preparing for the Local Examina tions of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and similar examinations. The Syndicates of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities often select these chapters as the subject for examination in a particular year. The Editor has accordingly drawn up the present Edition for the use of Candidates preparing for such Examinations. The Edition is an abridgement of the Editor's Acts of /ht Apostles, published by Messrs. Gill and Sons. The Introduction treats fully of the several subjects with which the Student should be acquainted. These are set forth in the Table of Contents. The Biographical and Geographical Notes, with the complete series of Maps, will be found to give the Student all necessary information, thns dispensing with the need for Atlas, Biblical Lictionary, and other aids. The text used in this volume is that of the Revised Version and is printed by permission of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but all editorial responsibility rests with the editor of the present volume. -

Absolute Dating of John the Baptist, the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ, and Paul the Apostle

Absolute Dating of John the Baptist, the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ, and Paul the Apostle Rainer Walter Kühne Bürgerstr. 4, 38118 Braunschweig, Germany e-mail: [email protected] I suggest the following scenario. In the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius (14-37), that is late in 28 or early in 29, John began to preach a baptism. Jesus healed and preached and was crucified on the Preparation Day, Friday 3 April 33 during a lunar eclipse. Thereafter the apostles began to preach and raising the number of believers from 120 to 5000. This caused a persecution where Saul converted to Paul late in 33. Afterwards Paul spent three years in Damascus, where Aretas IV was king. Thereafter Paul did his first travel which lasted for fourteen years, that is 36-50. This was followed by the council of the apostles late in 50. Thereafter Paul did his second travel which lasted for at least a year and six months. Then he did his third travel which lasted for at least two years and six months, that is 52-54. Afterwards he was imprisoned for two years by Antonius Felix until Porcius Festus became procurator of Judaea in 56. There is general agreement that Jesus Christ was a historical person. Experts differ in dating his crucifixion (between 27 and 34) and the council of the apostles (between 48 and 51). Here I would like to investigate these two open questions. In his Ioudaike archaiologia historian Josephus Flavius mentioned John the Baptist (Antiquitates Judaicae 18.5.2). He mentioned also that James, the brother of Jesus called Christus, was executed in 62 (Antiquitates Judaicae 20.200). -

From Permission to Prohibition: Paul and the Early Church on Mixed Marriage

From Permission to Prohibition: Paul and the Early Church on Mixed Marriage The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Cohen, Shaye J. D. 2011. From permission to prohibition: Paul and the early church on mixed marriage. In Paul's Jewish Matrix, ed. Thomas G. Casey and Justin Taylor, 259-291. Rome: Gregorian and Biblical Press. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33077876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Chapter 7 From Permission to Prohibition: Paul and the Early Church on Mixed Marriage Shaye J. D. Cohen, Harvard University Numerous ancient Jewish texts speak out against mixed marriage, the marriage of a Jew with a non-Jew. The poet Theodotus, the Temple Scroll, the book of Jubilees, the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, Philo, Josephus, and other works, written in Greek or Hebrew, in the land of Israel or the diaspora, clearly state that Jews are not to marry non-Jews. Rabbinic literature continues along the same trajectory. The reasons given for the prohibition usually reduce themselves to two: the non-Jewish spouse may turn the Jewish spouse away from the one true God and towards the worship of other, false gods; Jews constitute a ―holy‖ people that cannot tolerate foreign admixture. Some of these texts attempt to ground the prohibition in passages from the Bible, especially the Torah, while others are content to argue without scriptural support. -

Marcion and the Corruption of Paul's Gospel

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Judith M. Lieu Marcion and the Corruption of Paul’s Gospel Abstract: That Marcion’s authoritative texts were a form of the canonical Gospel of Luke and a Pauline corpus is well established, yet the relationship between these is far less certain. Although it is widely assumed that Marcion identified or authorised his gospel through a reading of Paul’s defence of his gospel in Gal 1–2, this relies heavily on Tertullian who is driven by his own rhetoric and agenda. Tracing the different defences by Irenaeus and Tertullian of the authority of the gospel and of conflict between Paul and Peter alerts us to the complex negotiations involved in the textualization of the early Christian message, and in the attempts to hold together the Pauline revolution and the remembering of Jesus traditions. Marcion represents a different stage in this process, and although we can reconstruct for him a narrative, it is one which is fragmentary and remains allusive. Contemporary attempts to get beyond the rhetoric and special pleading must always be sensitive to the ideological framing that has accompanied narratives of the past from the start. Keywords: Marcion, gospel, Paul, Irenaeus, Tertullian Judith M. Lieu: University of Cambridge, Faculty of Divinity, West Road, Cambridge CB3 9BS, United Kingdom, e-mail: [email protected] φασὶν δ᾽ὡς ἄρα τοῦ κατ᾽αὐτὸν εὐαγγελίου µνηµονεύειν ὁ Παῦλος εἴωθεν ὁπηνίκα ὡς περὶ ἰδίου τινὸς εὐαγγελίου γράφων ἔλεγεν “κατὰ τὸ εὐαγγέλιόν -

1 St Cyprian Treatise IX. on the Advantage of Patience (In Vol V, ANF)

St Cyprian Treatise IX. On the Advantage of Patience1 (in Vol V, ANF) Argument. -Cyprian Himself Briefly Sets Forth the Occasion of This Treatise at the Conclusion of His Epistle to Jubaianus as Follows: “Charity of Spirit, the Honour of Our College, the Bond of Faith, and Priestly Concord, are Maintained by Us with Patience and Gentleness. For This Reason, Moreover, We Have, with the Best of Our Poor Abilities, by the Permission and Inspiration of the Lord, Written a Pamphlet on the Benefit of Patience, “Which, for the Sake of Our Mutual Love, We Have Transmitted to You.” a.d. 256. 1. As I am about to speak, beloved brethren, of patience, and to declare its advantages and benefits, from what point should I rather begin than this, that I see that even at this time, for your audience of me, patience is needful, as you cannot even discharge this duty of hearing and learning without patience? For wholesome discourse and reasoning are then effectually learnt, if what is said be patiently heard. Nor do I find, beloved brethren, among the rest of the ways of heavenly discipline wherein the path of our hope and faith is directed to the attainment of the divine rewards, anything of more advantage, either as more useful for life or more helpful to glory, than that we who are labouring in the precepts of the Lord with the obedience of fear and devotion, should especially, with our whole watchfulness, be careful of patience.2 2. Philosophers also profess that they pursue this virtue; but in their case the patience is as false as their wisdom also is. -

As a Fisher of Men, Patience Is a Must I Have Been Fishing a Total of One Time in My Life, and It Was Among the Longest Three Ho

As A Fisher of Men, Patience is a Must I have been fishing a total of one time in my life, and it was among the longest three hours that I have ever had. It was on a summer day in 2006. I was serving as a transitional deacon, as priests become deacons first, and that summer was spent at a suburban parish, Saint Hubert’s in Chanhassen. It’s kind of a “get your feet wet” summer for what parish life will be like before you are ordained the following summer. An elderly parishioner got in touch with me and asked if I’d like to go fishing. Having never been, I thought sure, why not. After getting a one-day license, we headed to a local lake. After some struggles backing the boat into the lake (I kept shouting “turn” at the top of my lungs but he did not hear me, but that is another story), we went out onto the lake for a few hours that morning. Though he had some type of radar gizmo to let us know where fish might be, neither one of us got a thing. Hopefully though he was able to have a nice morning on the lake. Understandably, I think he knew I was a bit like a fish out of water trying this new activity, and did not call me back. Now if I liked fishing, I’m sure I could learn the sport. I’d probably read up on techniques and learn about spots and lakes, and I’m sure would eventually catch something. -

Read Book the Gospel According to Luke Kindle

THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO LUKE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James R Edwards | 859 pages | 30 May 2015 | William B Eerdmans Publishing Co | 9780802837356 | English | Grand Rapids, United States The Gospel According to Luke PDF Book Young man from Nain — It has been dated from the late 2nd century, although this dating is disputed. By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Notice. Some hold that Luke used Mark only as a complementary source for rounding out the material he took from other traditions. Gospel of Luke. The spirit of faithfulness to his material leads him to give over any attempt. Not peace, but a sword —53; — It is also very curious that the moment Paul disappears, that moment the history of Luke becomes mere surmise, confusion, and fable. All that I have said up to this point has been intended simply to prepare the way for a presentation of the general character of the Gospel according to Luke. His vocabulary is extensive and rich, and his style at times approaches that of classical Greek as in the preface, , while at other times it is quite Semitic -- -- often like the Septuagint the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT. The Character and Purpose of Luke's Christology. It is traditionally credited to St. Important Quotations Explained. Jesus Remembered. He gives it to us just as it came to him; so the Gospel according to Luke shows throughout the spirit of faithfulness to the truth, combined with a great deal of what you might call human interest, breadth of view, and love for humanity at large. -

St Paul the Apostle Parish

ST PAUL THE APOSTLE PARISH ROSTERS 9 / 10 SEPT 6.00PM VIGIL 8.00 AM 9.30 AM 6.00 PM ACOLYTES Q S I T 40 Buckleys Road, Winston Hills NSW 2153 MINISTERS OF Evelyn Brien Elly Benkovich Ken Abrahams Sean Trainor T: 9639 6516 W: www.stpaultheapostleparish.org COMMUNION Jan Francis Lesley Neylan Shani Tarrant Diana Roberts Parish Priest: Fr Raning Creta Assistant Priest: Fr Tovia Lui Deacon: Shinto Francis ALTAR SERVERS H I J K READERS Carmel Kevill Gabrielle Badaoui Veronica Reitano Esmerelda El-Bayeh 1†2 COMMENTATORS Diane Samson Emmy Cox Tony D’Souza Michael Hruby SUNDAY MASS TIMES WEEKDAY MASS TIMES PRESENTATION Maria Bisazza Saturday Evening Vigil 6.00pm (Exposition 4.30pm- 5.45pm) Monday 9.10am Volunteers Brogden Family Couples for Christ Sunday 8.00am, 9.30am and 6.00pm Tuesday 7.00pm (Exposition 6.00pm- 7.00pm) OF THE GIFTS Margaret Thomas Wednesday, Thursday & Friday 9.10am CHILDREN’S LITURGY Belinda Hamilton and Annabelle Hamilton RECONCILIATION Saturday 9.00am Saturday 4.30pm - 5.30pm CHURCH CLEANING Isabelle Badaoui, Eileen & Dennis Dunnachie, Judy Hince, Chris Leonard and Gemma Martin The Franciscan was next. He asked to touch the WINDOW CLEANING Joe & Yvonne El-Bayeh FROM FATHER RANING wounds in the hands and feet of Jesus before he Three holy, religious priests, a Dominican, a died. No sooner than Christ appeared and invited HOLY HOUR for Franciscan, and a Jesuit were in the same him, as he did Thomas, to examine His wounds. VOCATIONS hospice. All were near death. One evening, The dying priest touched Christ's hands and feet, wept with joy and was content and at peace. -

St. Paul the Apostle ~ Page 2 Paul’S Third Journey Took Place Between 52 and Illegal to Crucify Roman Citizens)

FIRST CENTURY; DIED MOST LIKELY 67 lem and became a leading persecutor of the new APOSTLE AND MARTYR Christian sect. He held the garments of those FEAST DAYS: JUNE 29 (WITH ST. PETER) who martyred St. Stephen by stoning, the event AND JANUARY�t. 25 (CONVERSION P) aul thethat sparked A�o the first greatstle persecution against the Church, and rounded up and arrested Chris- S THE APOSTLES began spreading the Good tians in Jerusalem, causing many of them to flee News to the known world, Jesus added the city. Saul, “breathing threats and murder” (Acts Aone more to their number, St. Paul, the last 9:1), obtained authority to carry the persecution apostle to whom the Risen Christ appeared: to Damascus, Syria. “Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also On this journey, Saul had one of the most to me” (1 Cor 15:8). This apparition, the thun- momentous conversion experiences in Chris- derclap event on the road to Damascus, brought tianity. A brilliant light from Heaven shone to Christianity one of the most zealous, fervent, brilliant, and holy of its saints. Saul, a Jew of the tribe of Benjamin, was “Saul had one of the most born in Tarsus, the wealthy capital of Cilicia momentous conversion (now modern south-central Turkey), which was a province of the Roman Empire. Saul thus was experiences in Christianity.” also born a Roman citizen and given the Latin name Paul, which he began to use after his or- about him and he heard a voice saying, “Saul, dination as a priest. -

50Cf82181a7fd8.49814146.Pdf

Little-known and remarkable facts about Paul and his times. MARVIN R. WILSON Tarsus, Paul’s birthplace, is at least Paul was a weaver of tent cloth living abroad in the first century. 4,000 years old. In 41 B.C., Antony from goats’ hair. The term, howev- Every major city had at least one and Cleopatra held a celebrated er, can also mean “leatherworker.” synagogue, and Rome had at least meeting there. Other early translations of Luke’s eleven. The Jewish population of term mean “maker of leather Rome alone was 40,000-50,000. At least seven of Paul’s relatives thongs” and “shoemaker.” are mentioned in the New Testa- Wine was a common drink of Paul’s ment. At the end of his letter to the Paul, the “Apostle to the Gen- day, but it was not the wine of our Romans, Paul greets as “relatives” tiles,”had plenty of opportunity to day. In the Greco-Roman world, Andronicus and Junia, Jason, Sosi- preach to Jews in his travels. There pure wine was considered strong pater, and Lucius. In addition, Acts were some four to five million Jews and unpleasant, so some Greeks mentions Paul’s sister and his neph- ew, who helped Paul in prison (Acts 23:16-22). It is possible that Paul’s “relative” Lucius is Luke, the author of the Gospel and the Acts of the Apos- tles. On his second missionary jour- ney, Paul may have gone to Troas (where Luke lived-or at least where he joined Paul) because he knew a relative he could stay with there (Acts 16:8, 11).