Paul and Asceticism in 1 Corinthians 9:27A Kent L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Problem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The rP oblem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions Edward Matusek University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Matusek, Edward, "The rP oblem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3733 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Problem of Evil in Augustine’s Confessions by Edward A. Matusek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Thomas Williams, Ph.D. Roger Ariew, Ph.D. Joanne Waugh, Ph.D. Charles B. Guignon, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 14, 2011 Keywords: theodicy, privation, metaphysical evil, Manichaeism, Neo-Platonism Copyright © 2011, Edward A. Matusek i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iii Chapter One: Introduction to Augustine’s Confessions and the Present Study 1 Purpose and Background of the Study 2 Literary and Historical Considerations of Confessions 4 Relevance of the Study for Various -

SELF-FLAGELLATION in the EARLY MODERN ERA Patrick

SELF-FLAGELLATION IN THE EARLY MODERN ERA Patrick Vandermeersch Self-fl agellation is often understood as self-punishment. History teaches us, however, that the same physical act has taken various psychologi- cal meanings. As a mass movement in the fourteenth century, it was primarily seen as an act of protest whereby the fl agellants rejected the spiritual authority and sacramental power of the clergy. In the sixteenth century, fl agellation came to be associated with self-control, and a new term was coined in order to designate it: ‘discipline’. Curiously, in some religious orders this shift was accompanied by a change in focus: rather than the shoulders or back, the buttocks were to be whipped instead. A great controversy immediately arose but was silenced when the possible sexual meaning of fl agellation was realized – or should we say, constructed? My hypothesis is that the change in both the name and the way fl agellation was performed indicates the emergence of a new type of modern subjectivity. I will suggest, furthermore, that this requires a further elaboration of Norbert Elias’s theory of the ‘civiliz- ing process’. A Brief Overview of the History of Flagellation1 Let us start with the origins of religious self-fl agellation. Although there were many ascetic practices in the monasteries at the time of the desert fathers, self-fl agellation does not seem to have been among them. With- out doubt many extraordinary rituals were performed. Extreme degrees 1 The following historical account summarizes the more detailed historical research presented in my La chair de la passion. -

Twenty Third Sunday in Ordinary Time September 5, 2021

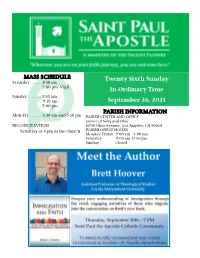

MASS SCHEDULE Twenty Sixth Sunday Saturday .......... 8:30 am 5:00 pm Vigil In Ordinary Time Sunday ............. 7:30 am 9:30 am September 26, 2021 5:00 pm PARISH INFORMATION Mon-Fri ............ 6:30 am and 5:30 pm PARISH CENTER AND OFFICE Corner of Selby and Ohio RECONCILIATION 10750 Ohio Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90024 Saturday at 4 pm in the church PARISH OFFICE HOURS Monday-Friday 9:00 am—4:00 pm Saturday 9:00 am-12:00 pm Sunday Closed Page 2 September 26, 2021 Dear Sisters and Brothers in Christ – The Annual Fall Festival is here! The theme is One Love, a response to the pandemic – one love that flows from God. Our Festival Team led by Wanda Ahmadi have taken every precaution in this time of COVID. To attend in person, full vaccination is strongly recommended and/or a COVID test within 72 hours of attending; masks are to be worn at all times except when eating or drinking; practice physical distancing; and, wash hands fre- quently. See you on the Ferris wheel! Our next faith formation program is a special presentation of a new book, “Immigration and Faith: Cultural, Biblical, and Theological Narratives” by professor of theology at Loyola Marymount University, Brett Hoo- ver on Thursday, September 30 at 7 PM in the Church. Brett utilizes vivid and engaging narratives of those who migrate to see migration through the lens of our faith. The book is available for purchase at the Parish Office and will be available at the presentation. You may attend online at St. -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

Idol Meat and Evangelization

Chapter 4 Idol Meat and Evangelization 1 Corinthians 8–9 UNDERSTANDING Pages 52 - 57 DISCUSSION Pages 58 - 64 Understanding / Idol Meat and Evangelization UNDERSTANDING WHAT DO I NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THIS PASSAGE? Read 1 Corinthians 8–9 The Big Picture As the Corinthians struggled with the problem of eating meat sacrificed to idols, St. Paul will use love and his own example to persuade them. At first, it doesn’t seem that the Corinthians’ problem with eating meat sacrificed to idols has much to do with us in the 21st century. But St. Paul’s words 2,000 years ago still have much to teach us today about care for fellow Christians and evangelizing others. Love and Knowledge (1 Corinthian 8:1–6) Continuing his responses to the Corinthians, St. Paul addresses the following question: Should Christians eat meat from animals slaughtered in the pagan temples during religious ceremonies? First, we must realize how ingrained this practice was in the lives of the Corinthians. Because of the large number of temples, and thus animal sacrifices, in Corinth, most meat was bought from a temple. Plus, the temples were the center of the social scene in Corinth. Weddings, birthdays, and other celebrations were celebrated in the temple with a meal. Business networking and success came through attending and hosting parties in the temple. To attend the party but not to eat the food offered would have been an offense to the host. It is mostly likely that the ones who wrote to St. Paul were okay with eating idol meat. -

1 Corinthians 9:19-23 a Model for Those Who Seek to Win Souls

Restoration Quarterly Volume 29 Number 3 Article 1 7-1-1987 1 Corinthians 9:19-23 A Model for Those Who Seek to Win Souls Kenneth V. Neller Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Neller, Kenneth V. (1987) "1 Corinthians 9:19-23 A Model for Those Who Seek to Win Souls," Restoration Quarterly: Vol. 29 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly/vol29/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Restoration Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ ACU. ISSN 0486-5642 ResLouaLton _ aauLeRl&' I Corinthians 9119-23 A Model for Those 'Who Seek to Wm Souls KENNE1H V. NELLER Lexington, Kentucky Only since the Second World War, perhaps from the impetus of a growing missions awareness, has modem scholarship given 1 Corinthians 9: 19-23 much attention. Scholars priorl o this time generally viewed these verses as having no exegetical significance other than a simple statement of Paul's missionary technique. Little work was done to relate these verses to the context of the epistle. This is no doubt why even as late as 1953, Clarence Tucker Craig could say of chapter 9 as a whole, "It does not directly advance the discussion of the immediate issue." 1 Recent scholars, however, have begun to recognize the significance of these verses.2 Chadwick goes so far as to use this passage in an attempt to understand Paul's method of dealing with all of the problems addressed in 1 Corinthians. -

The Virtue of Penance in the United States, 1955-1975

THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Maria Christina Morrow UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2013 THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Name: Morrow, Maria Christina APPROVED BY: _______________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Chair _______________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Member Mary Ann Spearin Chair in Catholic Theology _______________________________________ Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________________ Jana M. Bennett, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________________ William C. Mattison, III, Ph.D. Committee Member iii ABSTRACT THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Name: Morrow, Maria Christina University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation examines the conception of sin and the practice of penance among Catholics in the United States from 1955 to 1975. It begins with a brief historical account of sin and penance in Christian history, indicating the long tradition of performing penitential acts in response to the identification of one’s self as a sinner. The dissertation then considers the Thomistic account of sin and the response of penance, which is understood both as a sacrament (which destroys the sin) and as a virtue (the acts of which constitute the matter of the sacrament but also extend to include non-sacramental acts). This serves to provide a framework for understanding the way Catholics in the United States identified sin and sought to amend for it by use of the sacrament of penance as well as non-sacramental penitential acts of the virtue of penance. -

Charisma, Medieval and Modern

Charisma, Medieval and Modern Edited by Peter Iver Kaufman and Gary Dickson Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Peter Iver Kaufman and Gary Dickson (Eds.) Charisma, Medieval and Modern This book is a reprint of the special issue that appeared in the online open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) in 2012 (available at: http://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special_issues/charisma_medieval). Guest Editors Peter Iver Kaufman Jepson School, University of Richmond Richmond, VA, USA Gary Dickson School of History, Classics, and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh Edinburgh, EH, Scotland, UK Editorial Office MDPI AG Klybeckstrasse 64 Basel, Switzerland Publisher Shu-Kun Lin Production Editor Jeremiah R. Zhang 1. Edition 2014 0'3,%DVHO%HLMLQJ ISBN 978-3-03842-007-1 © 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. All articles in this volume are Open Access distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. However, the dissemination and distribution of copies of this book as a whole is restricted to MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. III Table of Contents List of Contributors ............................................................................................................... V Preface -

| 1 Corinthians | Week 14 Scripture Guide | 1 Corinthians 9:1-27

| 1 Corinthians | Week 14 Scripture Guide | 1 Corinthians 9:1-27 Biblical Context Paul has been writing about Christians not allowing their “right” (ἐξουσία, exousia , “authority”) to become a stumbling block to someone else (1 Cor 8:9). He ended chapter 8 with his assertion, “Therefore, if food makes my brother stumble, I will never eat meat, lest I make my brother stumble” (8:13).1 Paul now further shares how he surrenders his “rights” for the sake of the gospel.2 He opens by asking a series of rhetorical questions using his apostleship as the basis for what follows.3 Some in Corinth doubt his apostleship (9:2a) while Paul shows how the existence of the church in Corinth is evidence of his “apostleship in the Lord” (9:1-2; 2 Cor 3:1-3; Acts 18). If anyone has “rights” or spiritual authority in Corinth, it is Paul and other apostles. While he has asked Christians in Corinth to give up their rights for the sake of the gospel, he shows how he has done the same. In chapter 1, Paul addressed divisions in the church which had their root in the Corinthians viewing the teachers in terms of popular contemporary philosophy—involving the form and content of teaching (cf. 1:17; 2:1-5), but also their teachers’ means of support.4 “Philosophers and wandering missionaries in the Greco-Roman world made their living in one of four ways: fees, patronage, begging, and working. Each of these had both proponents and detractors, who viewed rival forms as not worthy of philosophy.”5 In 9:4-14, Paul explains that he is fully aware of his rights as a teacher and an apostle, which include the meeting of basic sustenance (9:4), taking a believing wife (9:5),6 and refraining from having to work for his own support (9:6). -

The Impact of Pilgrimage Upon the Faith and Faith-Based Practice of Catholic Educators

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators Rachel Capets The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Capets, R. (2018). The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Education)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/219 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE FAITH AND FAITH-BASED PRACTICE OF CATHOLIC EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy, Education The University of Notre Dame, Australia Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P. 23 August 2018 THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE CATHOLIC EDUCATOR Declaration of Authorship I, Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P., declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Education, University of Notre Dame Australia, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. -

Life with Augustine

Life with Augustine ...a course in his spirit and guidance for daily living By Edmond A. Maher ii Life with Augustine © 2002 Augustinian Press Australia Sydney, Australia. Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people: ► the Augustinian Province of Our Mother of Good Counsel, Australia, for support- ing this project, with special mention of Pat Fahey osa, Kevin Burman osa, Pat Codd osa and Peter Jones osa ► Laurence Mooney osa for assistance in editing ► Michael Morahan osa for formatting this 2nd Edition ► John Coles, Peter Gagan, Dr. Frank McGrath fms (Brisbane CEO), Benet Fonck ofm, Peter Keogh sfo for sharing their vast experience in adult education ► John Rotelle osa, for granting us permission to use his English translation of Tarcisius van Bavel’s work Augustine (full bibliography within) and for his scholarly advice Megan Atkins for her formatting suggestions in the 1st Edition, that have carried over into this the 2nd ► those generous people who have completed the 1st Edition and suggested valuable improvements, especially Kath Neehouse and friends at Villanova College, Brisbane Foreword 1 Dear Participant Saint Augustine of Hippo is a figure in our history who has appealed to the curiosity and imagination of many generations. He is well known for being both sinner and saint, for being a bishop yet also a fellow pilgrim on the journey to God. One of the most popular and attractive persons across many centuries, his influence on the church has continued to our current day. He is also renowned for his influ- ence in philosophy and psychology and even (in an indirect way) art, music and architecture. -

A Man Named Martin Part 1: the Man Session One Session

A Man Named Martin Part 1: The Man Session One Comprehensive Reformation Website: Concordia Seminary (St. Louis) has developed a great website on the Reformation. Luther's Formative Years: In this Concordia Theological Monthly article (April 1946), E. G. Schweibert offers a fascinating account of Luther’s formative years, up through his completion of elementary school. The Plague: This article describes the cause, transmission and symptoms of the plague that killed two of Luther’s colleagues at Erfurt. Observant Augustinians: The monastic movement called the Order of Saint Augustine traced its founding to Saint Augustine (d. 430). Before Luther’s time an observant movement started among the Augustinians to focus on increased spirituality. Welcome to a Day in the Life of a Monk: Experience a day in the life of a monk, from his early rising, to his praying, labor, and the overall austerity that marks a man’s monastic decision. Session Two In the Monastery The Flagellants: This fanatical and heretical sect took self-flagellation to an extreme 200 years before Luther’s time; their activities help explain the purposes of self-flagellation among monks like Luther. Of the Awful Judgment: For Awakening Fear in Oneself: Centuries before Luther, St. Anselm wrote about sin and righteousness. His meditations on the depth of our sinfulness help explain why Luther’s monastic period made his feelings of guilt and unworthiness increase. Johann von Staupitz: This is a biographical sketch of Luther’s Augustinian supervisor. Luther’s Trip to Rome Rome and Romans - - Martin Luther: This writing by Pastor Tom Browning certainly carries a Presbyterian bent, but its focus on historical detail helps explain the backdrop and particulars of Luther’s first trip to Rome, which greatly discouraged him.