Marcion and the Corruption of Paul's Gospel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fathers of the Church, Part 2: the Latin (Or Western) Fathers

Fathers of the Church, Part 2: The Latin (or Western) Fathers A previous In Focus explored some of the great Fathers of the Eastern, or Greek, Church. This week the Latin (Western) Fathers are highlighted. While there is no official list of the Fathers, since the fifth century the criteria for selection has been that the individuals lived holy lives, were orthodox in their teachings and writings, lived during antiquity (the first through seventh centuries) and have been approved by the Church. According to some historians, there are more than 100 total Church Fathers (East and West); many of the same names are found on the different lists. The Fathers helped define, establish and promote the dogmas of the Catholic faith. They not only explained and advanced Christianity, but they stood against those who would defame, deny or exploit our Lord, Jesus Christ. This author is not able to adequately measure or describe the sanctity of these men, who were popes, bishops, theologians, apologists and writers. Some are saints, and all gave themselves in the service of the Lord. Here are a handful among the giants from the Western Church who have the title Church Father. They are categorized by those who lived just before the Council of Nicea, those in the era of Nicea and those after the council, up through the seventh century. Part one about the Greek (Eastern) Church Fathers was published Jan. 21 and can be found at: bit.ly/fatherspart1. Ante-Nicea Fathers Tertullian (c. 155-220) Tertullian Public domain The Fathers of the Western Church begin with Tertullian in the second century. -

Twenty Third Sunday in Ordinary Time September 5, 2021

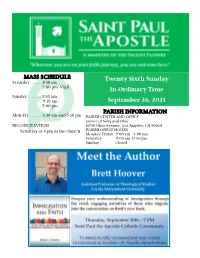

MASS SCHEDULE Twenty Sixth Sunday Saturday .......... 8:30 am 5:00 pm Vigil In Ordinary Time Sunday ............. 7:30 am 9:30 am September 26, 2021 5:00 pm PARISH INFORMATION Mon-Fri ............ 6:30 am and 5:30 pm PARISH CENTER AND OFFICE Corner of Selby and Ohio RECONCILIATION 10750 Ohio Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90024 Saturday at 4 pm in the church PARISH OFFICE HOURS Monday-Friday 9:00 am—4:00 pm Saturday 9:00 am-12:00 pm Sunday Closed Page 2 September 26, 2021 Dear Sisters and Brothers in Christ – The Annual Fall Festival is here! The theme is One Love, a response to the pandemic – one love that flows from God. Our Festival Team led by Wanda Ahmadi have taken every precaution in this time of COVID. To attend in person, full vaccination is strongly recommended and/or a COVID test within 72 hours of attending; masks are to be worn at all times except when eating or drinking; practice physical distancing; and, wash hands fre- quently. See you on the Ferris wheel! Our next faith formation program is a special presentation of a new book, “Immigration and Faith: Cultural, Biblical, and Theological Narratives” by professor of theology at Loyola Marymount University, Brett Hoo- ver on Thursday, September 30 at 7 PM in the Church. Brett utilizes vivid and engaging narratives of those who migrate to see migration through the lens of our faith. The book is available for purchase at the Parish Office and will be available at the presentation. You may attend online at St. -

The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus by Philip Schaff About ANF01

ANF01. The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus by Philip Schaff About ANF01. The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus by Philip Schaff Title: ANF01. The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.html Author(s): Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: The Ante-Nicene Christian library is meant to comprise translations into English of all the extant works of the Fathers down to the date of the first General Council held at Nice in A.D. 325. The sole provisional exception is that of the more bulky writings of Origen. It is intended at present only to embrace in the scheme the Contra Celsum and the De Principiis of that voluminous author; but the whole of his works will be included should the undertaking prove successful. Publication History: Text edited by Rev. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson and first published in Edinburgh, 1867. Additional introductionary material and notes provided for the American edition by A. Cleveland Coxe 1886. Print Basis: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, reprint 2001 Source: Logos Research Systems, Inc. Rights: Public Domain Date Created: 2002-10 Status: Proof reading, ThML markup and subject index for Version 3.0 by Timothy Lanfear General Comments: Hebrew and Greek were checked against page scans of the 1995 Hendrickson reprint by SLK; errors in the hard copy have not been corrected in this digitized text. Contributor(s): Timothy Lanfear (Markup) CCEL Subjects: All; Early Church; Classic; Proofed; LC Call no: BR60 LC Subjects: Christianity Early Christian Literature. -

St. Paul the Apostle1 by Kenneth John Paul Pomeisl2

St. Paul the Apostle1 by Kenneth John Paul Pomeisl2 St. Paul was born in the town of Tarsus in Cilicia which we today call Turkey around the year 3 A.D. His original name was actually Saul. He was a Pharisee which were a group of very devout Jews who were very serious about “the Law”. After Pentecost the Church, known then as “the Way”, slowly began to grow. As it did many of the Jews did not like this. They thought these newcomers were heretics. Saul was involved with putting these people in prison. He was at the execution of the first martyr, St. Stephen, who died by stoning. As he died St. Stephen asked God to forgive those who were killing him. Saul would continue to arrest every follower of the Way he could find. Some people believe that because of what St. Stephen did and how these people acted Saul started to have doubts about what he was doing but he would not change his mind. Then one day Saul was struck by a great light and blinded. As he was down here heard a voice asking “Saul, Saul, Why do you persecute me?” Saul asked this voice who he was and the reply was “I am Jesus, who you are persecuting”. After this Saul has his sight restored and becomes a Christian himself. After a while he is sent on missions to preach the Gospel to the Gentiles (non-Jews). St. Paul endures many hardships but creates many Churches and during this time writes many of his letters which we know today as Epistles in the New Testament. -

Thomas Aquinas and Irenaeus on the Divine and Natural Law

Randall B. Smith University of St. Thomas, Houston, Texas [email protected] 13 (2020) 2: 175–187 ORCID: 0000-0003-4262-4279 ISSN (print) 1689-5150 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12775/BPTh.2020.007 ISSN (online) 2450-7059 Thomas Aquinas and Irenaeus on the Divine and Natural Law Abstract. Thomas’s account of the natural law owes a large debt to Aristotle and other early Greek philosophers back to Heraclitus. This debt has long been known and dis- cussed. Largely unrecognized, however, are the crucial influences of the early Greek Fathers of the Church who mediated this classical philosophical heritage to the Chris- tian world. They were the first to set out the relationship between the natural law, the Old Law, and grace which would have a decisive influence on Aquinas’s famous “trea- tise on law” in the Summa of Theology. In this paper, I analyze Thomas’s mature work on the natural law in STh I–II, qq. 90–108 and show how the roots of this view can be traced to the earliest Church, especially in the writings of the second century bishop and martyr, St. Irenaeus of Lyons. Of special interest is how Irenaeus transformed the Greek-Aristotelian notion of physis and “natural law” within the context of his discus- sion of the goodness of creation and the Mosaic Law, contrary to the popular Gnostic views of his day. Keywords: Thomas Aquinas; Ireneaus; natural law; divine law; Mosaic Law; Old Law; Adversus Haereses. 1. A Common Narrative about the Natural Law: The Missing Historical Piece common narrative about the natural law divides its development -

FR. WILLIAM B. GOLDIN, S.T.D. Intro to St. Thomas Aquinas the Sources of Catholic Theology

FR. WILLIAM B. GOLDIN, S.T.D. CLASS 2, SACRA DOCTRINA: INTRODUCTION TO THEOLOGY 3 SEPTEMBER 2020 ST. IRENAEUS CHURCH—CYPRESS, CALIFORNIA Intro to St. Thomas Aquinas The Sources of Catholic Theology Finishing Class 1: Faith and Reason in the Scholastic Period I. Theology as Scientia: Intro to Saint Thomas Aquinas Class 2, Part I: Theology as Scientia: Intro to Saint Thomas Aquinas I. The Contribution of St. Thomas Aquinas to Theology II. How to Read Aquinas ST Ia, q. 1, aa. 1, 2, and 8: Article 1. Whether, besides philosophy, any further doctrine is required? Objection 1. It seems that, besides philosophical science, we have no need of any further knowledge. For man should not seek to know what is above reason: "Seek not the things that are too high for thee" (Sirach 3:22). But whatever is not above reason is fully treated of in philosophical science. Therefore any other knowledge besides philosophical science is superfluous. Objection 2. Further, knowledge can be concerned only with being, for nothing can be known, save what is true; and all that is, is true. But everything that is, is treated of in philosophical science—even God Himself; so that there is a part of philosophy called theology, or the divine science, as Aristotle has proved (Metaph. vi). Therefore, besides philosophical science, there is no need of any further knowledge. On the contrary, It is written (2 Timothy 3:16): "All Scripture, inspired of God is profitable to teach, to reprove, to correct, to instruct in justice." Now Scripture, inspired of God, is no part of philosophical science, which has been built up by human reason. -

What Happened in the First Century -- Creation of New Testament Writings; Spread of Christianity; Rise of Persecutions

What Happened in the First Century -- Creation of New Testament Writings; Spread of Christianity; Rise of Persecutions • The words and sayings of Jesus are collected and preserved. New Testament writings are completed. • A new generation of leaders succeeds the apostles. Nevertheless, expectation still runs high that the Lord may return at any time. The end must be close. • The Gospel taken through a great portion of the known world of the Roman empire and even to regions beyond. • New churches at first usually begin in Jewish synagogues around the empire and Christianity is seen at first as a part of Judaism. • The Church faces a major crisis in understanding itself as a universal faith and how it is to relate to its Jewish roots. • Christianity begins to emerge from its Jewish womb. A key transition takes place at the time of Jewish Revolt against Roman authority. In 70 AD Christians do not take part in the revolt and relocate to Pella in Jordan. • The Jews at Jamnia in 90 AD confirm the canon of the Hebrew Scriptures. The same books are recognized as authoritative by Christians. • Persecutions test the church. Jewish historian Josephus seems to express surprise that they are still in existence in his Antiquities in latter part of first century. • Key persecutions include Nero at Rome who blames Christians for a devastating fire that ravages the city in 64 AD He uses Christians as human torches to illumine his gardens. • Emperor Domitian demands to be worshiped as "Lord and God." During his reign the book of Revelation is written and believers cannot miss the reference when it proclaims Christ as the one worthy of our worship. -

A:Cts of the Apostles (Revised Version)

THE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE EDITION. A:CTS OF THE APOSTLES (REVISED VERSION) (CHAPTERS I.-XVI.) WITH BY THK REV. F. MARSHALL, M.A., (Lau Ezhibition,r of St, John's College, Camb,idge)• Recto, of Mileham, formerly Principal of the Training College, Ca11narthffl. and la1ely Head- Master of Almondbury Grammar School, First Edition 1920. Ten Impressions to 1932. Jonb.on: GEORGE GILL & SONS, Ln., MINERVA HOUSE, PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.4. MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ACTS OPTBE APOSTLES . <t. ~ -li .i- C-4 l y .A. lO 15 20 PREFACE. 'i ms ~amon of the first Sixteen Chapters of the Acts of the Apostles is intended for the use of Students preparing for the Local Examina tions of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and similar examinations. The Syndicates of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities often select these chapters as the subject for examination in a particular year. The Editor has accordingly drawn up the present Edition for the use of Candidates preparing for such Examinations. The Edition is an abridgement of the Editor's Acts of /ht Apostles, published by Messrs. Gill and Sons. The Introduction treats fully of the several subjects with which the Student should be acquainted. These are set forth in the Table of Contents. The Biographical and Geographical Notes, with the complete series of Maps, will be found to give the Student all necessary information, thns dispensing with the need for Atlas, Biblical Lictionary, and other aids. The text used in this volume is that of the Revised Version and is printed by permission of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but all editorial responsibility rests with the editor of the present volume. -

Trinitarian & Christological Orthodoxy

A Brief Overview of Christian Orthodoxy: Trinitarian and Christological Controversies By Charles Williams Last revised: August 9, 2009 The Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed (381 A.D.) Concerning Against Text God the Father Gnosticism & We believe in one God Marcionism The Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, Valentinianism And of all things visible and invisible; God the Son And in one Lord Jesus Christ The only-begotten Son of God, Adoptionism Begotten of his Father before all time, God of God, Light of Light, Arianism Very God of very God, Begotten, not created, Being of one substance with the Father, By whom all things were made; Who for us and our salvation Came down from heaven, Adoptionism And was incarnate by the Holy Ghost Of the virgin Mary, Apollinarianism And was made man; Docetism And was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate; He suffered and was buried; And the third day he rose again According to the Scriptures, And ascended into heaven, And sits at the right hand of the Father; Modalism And he shall come again, with glory, To judge both the quick and the dead; Whose kingdom shall have no end. God the Holy Spirit Macedonianism And we believe in the Holy Ghost the Lord And Giver of Life Who proceeds from the Father [and the Son]*; Who with the Father and the Son Together is worshiped and glorified; Marcionism Who spake by the Prophets. The Church And we believe in one holy Catholic & Last Things And Apostolic Church; Donatism We acknowledge one Baptism For the remission of sins; Gnosticism And we look for the resurrection of the dead, And the life of the world to come. -

Early-Christianity-Timeline.Pdf

Pagan Empire Christian Empire 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 1 AD Second 'Bishop' of Rome. Pupil of Student of Polycarp. First system- Bishop of Nyssa, brother of Basil. Pope. The Last Father of the Peter. Author of a letter to Corinth, atic theologian, writing volumi- Bishop of Original and sophisticated theologi- model of St Gregory the Church. First of the St John of (1 Clement), the earliest Christian St Clement of Rome nously about the Gospels and the St Irenaeus St Cyprian Carthage. an, writing on Trinitarian doctrine Gregory of Nyssa an ideal Scholastics. Polymath, document outside the NT. church, and against heretics. and the Nicene creed. pastor. Great monk, and priest. Damascus Former disciple of John the Baptist. Prominent Prolific apologist and exegete, the Archbishop of Constantinople, St Leo the Pope. Able administrator in very Archbishop of Seville. Encyclopaedist disciple of Jesus, who became a leader of the most important thinker between Paul brother of Basil. Greatest rhetorical hard times, asserter of the prima- and last great scholar of the ancient St Peter Judean and later gentile Christians. Author of two St Justin Martyr and Origen, writing on every aspect stylist of the Fathers, noted for St Gregory Nazianzus cy of the see of Peter. Central to St Isidore world, a vital link between the learning epistles. Source (?) of the Gospel of Mark. of life, faith and worship. writing on the Holy Spirit. Great the Council of Chalcedon. of antiquity and the Middle Ages. Claimed a knowledge and vision of Jesus independent Pupil of Justin Martyr. Theologian. -

Absolute Dating of John the Baptist, the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ, and Paul the Apostle

Absolute Dating of John the Baptist, the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ, and Paul the Apostle Rainer Walter Kühne Bürgerstr. 4, 38118 Braunschweig, Germany e-mail: [email protected] I suggest the following scenario. In the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius (14-37), that is late in 28 or early in 29, John began to preach a baptism. Jesus healed and preached and was crucified on the Preparation Day, Friday 3 April 33 during a lunar eclipse. Thereafter the apostles began to preach and raising the number of believers from 120 to 5000. This caused a persecution where Saul converted to Paul late in 33. Afterwards Paul spent three years in Damascus, where Aretas IV was king. Thereafter Paul did his first travel which lasted for fourteen years, that is 36-50. This was followed by the council of the apostles late in 50. Thereafter Paul did his second travel which lasted for at least a year and six months. Then he did his third travel which lasted for at least two years and six months, that is 52-54. Afterwards he was imprisoned for two years by Antonius Felix until Porcius Festus became procurator of Judaea in 56. There is general agreement that Jesus Christ was a historical person. Experts differ in dating his crucifixion (between 27 and 34) and the council of the apostles (between 48 and 51). Here I would like to investigate these two open questions. In his Ioudaike archaiologia historian Josephus Flavius mentioned John the Baptist (Antiquitates Judaicae 18.5.2). He mentioned also that James, the brother of Jesus called Christus, was executed in 62 (Antiquitates Judaicae 20.200). -

Ecumenical Councils Preparing for Next Week (Disciple 6–Eucharist 1)

January St. Dominic’s RCIA Program Disciple The Church: 15 History & Teaching 4 Goal • Having switched the Disciple 4 & 5 weeks, we looks at an overview of the Sacraments last week (Disciple 5), and explored the Sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation. These Sacraments are two of the three that initiate us into the Church community, and into Christ’s body and mission. This week we’ll continue to unpack the meaning of Church by looking broadly at its history one the last 2000 years. We’ll also explore it’s role as Teacher. How does the Church function in and through history? How does God walk with the Church through it all? Agenda • Welcome/Housekeeping (10) • Questions & Answers • Introduction to the Rosary (15) Discussion (15): • If the Church is The Body of Christ, what does this mean for Christ’s presence in the world through history and in the world today? • What do I admire about the Catholic Church’s activity in history? Does any part of the Church’s activity in history disturb or upset me? • How do I (might I) listen to what the Church has to say today? What is my approach/attitude to the Church as “Teacher”? • Presentation: The Church: History (35) • Break (10) • Presentation: The Church: Teaching & Belief (30) • Discussion (time permitting): • What is special to this moment in history? • What is the Good News of Christ & the Church that speaks to this moment in history? • How can the body of Christ proclaim & witness the Gospel and walk with others today? Housekeeping Notes • Rite of Acceptance: February 10th at the 11:30am and 5:30 Masses.