THE APOSTLE PAUL and the INTROSPECTIVE CONSCIENCE of the WEST * KRISTER STENDAHL HARVARD DIVINITY SCHOOL to Henry J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

God's Repentance-Enabling Forgiveness

64 Copyright © 2001 The Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University God’s Repentance-Enabling Forgiveness BY RALPH C. WOOD It is the Easter event—the Father’s gracious rejection of our dreadful rejection, the Son’s awful assumption of the world’s entire burden of sin, the Holy Spirit’s infusion of forgiveness into our lives—that provides our only hope for repentance. A Flannery O’Connor short story shows this extravagant claim is not mere theological word-play, but a matter of life and death. oltaire famously declared, “God forgives because it’s his business.” The great atheist could refer blithely to the God in whom he did Vnot believe because he also had contempt for the chief Christian virtue. Mercy and pity and forgiveness are not the traits of heroic peoples and cultures. The Greeks, for example, sanctioned pity only for the weak and the helpless, never for the strong and the guilty. Thus did Voltaire aim to trivialize forgiveness by turning it into something automatic, making it a matter of rote, thus denying it any real significance. Yet the old skeptic spoke more truly than he knew. In the profound original sense of the word, forgiveness is indeed God’s business: his essential occupation, his constant activity, his diligent engagement—indeed, his very nature. Thus it is meant to form our fundamental character as Christians. GOD’S FORGIVENESS PRECEDES REPENTANCE The common assumption, found even in the most standard textbooks and dictionaries of theology, is that our forgiveness remains conditional God’s Repentance-Enabling Forgiveness 65 upon our repentance: first we repent, and then God forgives. -

Twenty Third Sunday in Ordinary Time September 5, 2021

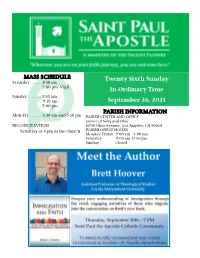

MASS SCHEDULE Twenty Sixth Sunday Saturday .......... 8:30 am 5:00 pm Vigil In Ordinary Time Sunday ............. 7:30 am 9:30 am September 26, 2021 5:00 pm PARISH INFORMATION Mon-Fri ............ 6:30 am and 5:30 pm PARISH CENTER AND OFFICE Corner of Selby and Ohio RECONCILIATION 10750 Ohio Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90024 Saturday at 4 pm in the church PARISH OFFICE HOURS Monday-Friday 9:00 am—4:00 pm Saturday 9:00 am-12:00 pm Sunday Closed Page 2 September 26, 2021 Dear Sisters and Brothers in Christ – The Annual Fall Festival is here! The theme is One Love, a response to the pandemic – one love that flows from God. Our Festival Team led by Wanda Ahmadi have taken every precaution in this time of COVID. To attend in person, full vaccination is strongly recommended and/or a COVID test within 72 hours of attending; masks are to be worn at all times except when eating or drinking; practice physical distancing; and, wash hands fre- quently. See you on the Ferris wheel! Our next faith formation program is a special presentation of a new book, “Immigration and Faith: Cultural, Biblical, and Theological Narratives” by professor of theology at Loyola Marymount University, Brett Hoo- ver on Thursday, September 30 at 7 PM in the Church. Brett utilizes vivid and engaging narratives of those who migrate to see migration through the lens of our faith. The book is available for purchase at the Parish Office and will be available at the presentation. You may attend online at St. -

Reconciliation

RECONCILIATION a Short Guide The sacrament of Reconciliation is the story of God's love that never turns away from us. What is Reconciliation? Reconciliation (also known as Confession or Penance) is a sacrament instituted by Jesus Christ in His love and mercy to offer sinners forgiveness for offenses committed against God. At the same time, sinners reconcile with the Church because it is also wounded by our sins. Every time we sin, we hurt ourselves, other people and God. In Reconciliation, we acknowledge our sins before God and His Church. We express our sorrow in a meaningful way, receive the forgiveness of Christ and His Church, make reparation for what we have done and resolve to do better in the future. The forgiveness of sins involves four parts: • Contrition : a sincere sorrow for having offended God, and the most important act of the penitent. There can be no forgiveness of sin if we do not have sorrow and a firm resolve not to repeat our sin. The Return of the Prodigal Son Rembrandt - 1669 • Confession : confronting our sins in a profound way to God by speaking about them —aloud— to the priest. • Penance : an important part of our healing is the “penance” the priest imposes in reparation for our sins. Absolution • : the priest speaks the words by which “God, the Father of Mercies” reconciles a sinner to Himself through the merits of the Cross. Rite of Reconciliation Reconciliation may be face-to-face or anonymous, with a screen between you and the priest. Choose the option that is the most comfortable for you. -

The Fifth and Sixth Trumpets (Rev 9)

THE FIFTH AND SIXTH TRUMPETS (REV 9) Read Revelation 9:1-21 (NIV) **What Scholars Say** REV 9:[1] The fifth angel sounded his trumpet, and I (John) saw a star that had fallen from the sky to the earth. The star was given the key to the shaft of the Abyss. THE FIFTH TRUMPET (9:1-11) VERSE 1 - REV 9:[1] The fifth angel sounded his trumpet, and I (John) saw a star that had fallen from the sky to the earth. "A star" sometimes signifies one in a high position or even a supernatural being. “There shall come a star out of Jacob" (Num 24:17); Angels are called "stars" (Job. 38:7); in Isa 14:12 we have Satan referred to as “How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning!" The star that had fallen from the sky to the earth. It seems, therefore, that Satan himself is referred to by this symbol. The words he in verses 2 and king in verse 11, show that this is a person rather than a literal star. The star was given the key to the shaft of the Abyss. Satan or this demonic angel was given a key to the shaft of the Abyss or the bottomless pit. The Abyss or bottomless pit is a place in the depths of the earth where evil spirits were thought to be imprisoned (Luke 8:31). Satan then is pictured as opening the lid or the door (that can be closed or locked) to this Abyss, so that demons can be released to inflict men and women on the earth. -

The Virtue of Penance in the United States, 1955-1975

THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Maria Christina Morrow UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2013 THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Name: Morrow, Maria Christina APPROVED BY: _______________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Chair _______________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Member Mary Ann Spearin Chair in Catholic Theology _______________________________________ Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________________ Jana M. Bennett, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________________ William C. Mattison, III, Ph.D. Committee Member iii ABSTRACT THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Name: Morrow, Maria Christina University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation examines the conception of sin and the practice of penance among Catholics in the United States from 1955 to 1975. It begins with a brief historical account of sin and penance in Christian history, indicating the long tradition of performing penitential acts in response to the identification of one’s self as a sinner. The dissertation then considers the Thomistic account of sin and the response of penance, which is understood both as a sacrament (which destroys the sin) and as a virtue (the acts of which constitute the matter of the sacrament but also extend to include non-sacramental acts). This serves to provide a framework for understanding the way Catholics in the United States identified sin and sought to amend for it by use of the sacrament of penance as well as non-sacramental penitential acts of the virtue of penance. -

Premillennialism in the New Testament: Five Biblically Doctrinal Truths

MSJ 29/2 (Fall 2018) 177–205 PREMILLENNIALISM IN THE NEW TESTAMENT: FIVE BIBLICALLY DOCTRINAL TRUTHS Gregory H. Harris Professor of Bible Exposition The Master’s Seminary Many scholars hold that premillennial statements are found only in Revelation 20:1–10. Although these verses are extremely important in supporting the premillen- nial doctrine, many other verses throughout the New Testament also offer support for premillennialism. Our study limits itself to five biblically doctrinal premillennial truths from the New Testament that seamlessly blend throughout the Bible with the person and work—and reign—of Jesus the Messiah on earth after His Second Com- ing. * * * * * Introduction Whenever discussions between premillennialists and amillennialists occur, Revelation 19 and 20 is usually the section of Scripture on which many base their argumentation, especially Revelation 20:1–10. Before we examine these specific pas- sages, we know that God has already made several prophecies elsewhere. And how one interprets these passages has been determined long before by how those other related futuristic biblical texts have already been interpreted, before ever approaching certain crucial biblical passages such as Revelation 20:1–10. So, as we shall see, one should actually end the argumentation for this important component of eschatological theology in Revelation 19–20, not start there. In setting forth the New Testament case for premillennialism we will present the following: (1) a presentation of three of the five premillennial biblical truths -

NB 377 Transcript

Naked Bible Podcast Episode 377: Revelation 9 Naked Bible Podcast Transcript Episode 377 Revelation 9 May 22, 2021 Teacher: Dr. Michael S. Heiser (MH) Host: Trey Stricklin (TS) Episode Summary Revelation 9 reveals John’s vision of the fifth and six trumpet judgments. Several interpretive issues are immediately apparent. What is the nature of the angel with the key to the bottomless pit (Rev 9:1)? Is this angel the same or different than that in Rev 9:11 or Abbadon/Apollyon? Who or what is being released from the bottomless pit (Rev 9:3-11)? These questions take the reader into the wider question of whether Revelation’s apocalyptic descriptions should be read in terms of modern analogies. In this episode we discern how the release of evil supernatural beings from the bottomless pit has clear connections to how Second Temple Jewish texts and 2 Peter describe the imprisoned Watchers, the sons of God of Genesis 6:1-4 infamy, and how the odd descriptions of those beings in insect and animal form have clear, abundant antecedents in the Old Testament. Transcript TS: Welcome to the Naked Bible Podcast, Episode 377: Revelation 9. I’m the layman, Trey Stricklin, and he’s the scholar, Dr. Michael Heiser. Hey, Mike! What's going on? MH: Well, I have a pug update. The pugs have now been introduced to the pool properly. TS: With life jackets? MH: With life jackets, of course. And their attitude toward the pool has moved from hysteria to mild hysteria. [laughter] They didn’t like it. -

St. Paul the Apostle1 by Kenneth John Paul Pomeisl2

St. Paul the Apostle1 by Kenneth John Paul Pomeisl2 St. Paul was born in the town of Tarsus in Cilicia which we today call Turkey around the year 3 A.D. His original name was actually Saul. He was a Pharisee which were a group of very devout Jews who were very serious about “the Law”. After Pentecost the Church, known then as “the Way”, slowly began to grow. As it did many of the Jews did not like this. They thought these newcomers were heretics. Saul was involved with putting these people in prison. He was at the execution of the first martyr, St. Stephen, who died by stoning. As he died St. Stephen asked God to forgive those who were killing him. Saul would continue to arrest every follower of the Way he could find. Some people believe that because of what St. Stephen did and how these people acted Saul started to have doubts about what he was doing but he would not change his mind. Then one day Saul was struck by a great light and blinded. As he was down here heard a voice asking “Saul, Saul, Why do you persecute me?” Saul asked this voice who he was and the reply was “I am Jesus, who you are persecuting”. After this Saul has his sight restored and becomes a Christian himself. After a while he is sent on missions to preach the Gospel to the Gentiles (non-Jews). St. Paul endures many hardships but creates many Churches and during this time writes many of his letters which we know today as Epistles in the New Testament. -

Repentance, Penance, & the Forgiveness of Sins

REPENTANCE, PENANCE, & THE FORGIVENESS OF SINS Catholic translations of the Bible have often used the words “repentance” and “penance” interchangeably. Compare the Douay- Rheims Version with the New American Catholic Bible at Acts 2:38 and Acts 26:20 and you will see that these words (repentance & penance) are synonymous, words carrying the same meaning as the another. The Catholic Dictionary published by “Our Sunday Visitor”, a Catholic publication defines these words in the following ways: Repentance = Contrition for sins and the resulting embrace of Christ in conformity to Him. Penance or Penitence = Spiritual change that enables a sinner to turn away from sin. The virtue that enables human beings to acknowledge their sins with true contrition and a firm purpose of amendment. If there is any difference of meaning, I would suggest from pondering Greek definitions, that repentance (from the New Testament) 1 focuses on a change of heart, a change of mind and penance centers on the works of faith that this change of heart has produced. But both the change of heart and the works of faith go together; they are part of the same package. The Church has always taught that Christ’s death and resurrection brought reconciliation between God and humanity and that “the Lord entrusted the ministry of reconciliation to the Church.”1 The catechism teaches that because sin often wrongs the neighbor, while absolution forgives sin, “it does not remedy all the disorders sin has caused,”2 therefore the sinner must still recover his full spiritual health by doing works meet for repentance, that is, prove your repentance by what you do. -

A:Cts of the Apostles (Revised Version)

THE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE EDITION. A:CTS OF THE APOSTLES (REVISED VERSION) (CHAPTERS I.-XVI.) WITH BY THK REV. F. MARSHALL, M.A., (Lau Ezhibition,r of St, John's College, Camb,idge)• Recto, of Mileham, formerly Principal of the Training College, Ca11narthffl. and la1ely Head- Master of Almondbury Grammar School, First Edition 1920. Ten Impressions to 1932. Jonb.on: GEORGE GILL & SONS, Ln., MINERVA HOUSE, PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.4. MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ACTS OPTBE APOSTLES . <t. ~ -li .i- C-4 l y .A. lO 15 20 PREFACE. 'i ms ~amon of the first Sixteen Chapters of the Acts of the Apostles is intended for the use of Students preparing for the Local Examina tions of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and similar examinations. The Syndicates of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities often select these chapters as the subject for examination in a particular year. The Editor has accordingly drawn up the present Edition for the use of Candidates preparing for such Examinations. The Edition is an abridgement of the Editor's Acts of /ht Apostles, published by Messrs. Gill and Sons. The Introduction treats fully of the several subjects with which the Student should be acquainted. These are set forth in the Table of Contents. The Biographical and Geographical Notes, with the complete series of Maps, will be found to give the Student all necessary information, thns dispensing with the need for Atlas, Biblical Lictionary, and other aids. The text used in this volume is that of the Revised Version and is printed by permission of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but all editorial responsibility rests with the editor of the present volume. -

Hebrew Roots Perversion of Repentance

Hebrew Roots Heresy (Part 1) The Perversion of ‘Repentance’ By Tim Warner © www.4windsfellowships.net It is remarkable that one of the most serious errors that infected early Christianity, that was officially renounced by the Jerusalem council,1 and was so soundly refuted by the Apostle Paul in Galatians, could make the kind of come-back that we see today. Yet is spreads like cancer among God’s people. Paul’s leaving Timothy behind at Ephesus was to counter the ‘Hebrew Roots’ heresy that was continually undermining his efforts to spread the Gospel among the nations. 1 Timothy 1:1-11 1 Paul, an apostle of Jesus Christ, by the commandment of God our Savior and the Lord Jesus Christ, our hope, 2 To Timothy, a true son in the faith: Grace, mercy, and peace from God our Father and Jesus Christ our Lord. 3 As I urged you when I went into Macedonia – remain in Ephesus that you may charge some that they teach no other doctrine, 4 nor give heed to fables and endless genealogies, which cause disputes rather than godly edification which is in faith. 5 Now the purpose of the commandment is love from a pure heart, from a good conscience, and from sincere faith, 6 from which some, having strayed, have turned aside to idle talk, 7 desiring to be teachers of the law, understanding neither what they say nor the things which they affirm. 8 But we know that the law is good if one uses it lawfully, 9 knowing this: that the law is not made for a righteous person, but for the lawless and insubordinate, for the ungodly and for sinners, for the unholy and profane, for murderers of fathers and murderers of mothers, for manslayers, 10 for fornicators, for sodomites, for kidnappers, for liars, for perjurers, and if there is any other thing that is contrary to sound doctrine, 11 according to the glorious gospel of the blessed God which was committed to my trust. -

Israel's Repentance and the Kingdom of God * * *

MSJ 27/1 (Spring 2016) 161–86 ISRAEL’S REPENTANCE AND THE KINGDOM OF GOD Michael J. Vlach Professor of Theology The Master’s Seminary The exact timing of Jesus’ return and the kingdom of God is known only to God. Yet in His sovereignty God has determined that the return of Jesus the Mes- siah is closely linked with the repentance of national Israel. This article examines both Old and New Testament texts that reveal a close connection between Israel’s repentance and the coming kingdom of God. * * * * * Introduction This article examines the connection between national Israel’s repentance and the kingdom of God. The argument promoted here is that the kingdom’s coming to earth is connected with and contingent upon Israel’s repentance.1 God is sovereign over all matters, and His universal kingdom extends over all, yet He has determined that the arrival of the mediatorial kingdom2 on earth is connected with Israel’s turning from sin and unbelief. This position, that the kingdom’s timing is related to national Israel’s repentance, is not popular and is often rejected. For example, the amillennial theologian, Kim Riddlebarger states, “But the New Testament knows nothing of a kingdom offered and kingdom withdrawn according to the whims of unbelieving Is- rael.”3 Yet the biblical evidence for the kingdom’s arrival being related to Israel’s repentance is strong, with multiple passages in both testaments supporting it. This is an oft-neglected truth, even among those who affirm a future for national Israel. Yet it is an important part of the Bible’s storyline.