Art and Culture As an Urban Development Tool a Diachronic Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Profile for the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Theatre

Khamar Hopkins Sunday, February 24, 2019 AAD 612 - Marketing and the Arts Michael Crowley Community Profile for The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Theatre The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Theatre, or better known as the Parkway, is a historic theatre located in the heart of Baltimore’s Station North Arts and Entertainment District that recently reopened its doors in the spring of 2017. The Parkway first opened its doors on October 23rd, 1915, with the feature premiere of Zaza, directed by Hugh Ford and Edwin S. Porter, and starring Pauline Fredrick.i During its first decade the Parkway would screen Paramount movies, had an orchestra, an organ, a cameraman, and could seat up to 1100 patrons. In 1926 the theatre was purchased and remodeled by Loews Incorporated, also known as Loew’s Cineplex Entertainment Corporation (as of January 26, 2006, Loews was acquired by AMC Entertainment Inc.)ii and 2 years later it got rid of its orchestra for Vitaphone and Movietone sound systems, and could now only seat 950 customers. The theatre would continue to function as a Loews theatre until it closed during the summer of 1952. With its next owner, Morris Mechanic, the Parkway had a short-lived season as a live theatre before it closed again. On May 24th, 1956, the Parkway reopened under the new name, 5 West, with the premiere of Ladykillers, and started rebranding itself as an art-house cinema. The new 5 West cinema could only hold 435 guests and provided great entertainment to the local community along with its neighboring theatres, but it started to struggle in the late 1970’s and then closed its doors again in the winter of 1978. -

Artists Are a Tool for Gentrification’: Maintaining Artists and Creative Production in Arts Districts

International Journal of Cultural Policy ISSN: 1028-6632 (Print) 1477-2833 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gcul20 ‘Artists are a tool for gentrification’: maintaining artists and creative production in arts districts Meghan Ashlin Rich To cite this article: Meghan Ashlin Rich (2017): ‘Artists are a tool for gentrification’: maintaining artists and creative production in arts districts, International Journal of Cultural Policy, DOI: 10.1080/10286632.2017.1372754 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2017.1372754 Published online: 06 Sep 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 263 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gcul20 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CULTURAL POLICY, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2017.1372754 ‘Artists are a tool for gentrification’: maintaining artists and creative production in arts districts Meghan Ashlin Rich Department of Sociology/Criminal Justice, University of Scranton, Scranton, PA, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This study investigates the relationship between arts-themed development Received 7 June 2017 and the strategies used by neighborhood stakeholders, including artists Accepted 16 August 2017 and other marginalized populations, to maintain their place in gentrifying KEYWORDS arts and cultural districts. Using a case study of a state-sanctioned Arts & Artist communities; creative Entertainment District in Baltimore, MD (U.S.A.), I find that the organizations placemaking; gentrification; that are ‘thoughtful’ in their development actively seek to maintain the urban planning and policy production of arts and the residency of artists in the neighborhood into perpetuity. -

Front and Center: a 5-Year Equity Plan for Central Baltimore

AUGUST 2017 A 5-year Equity Plan for Central Baltimore TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary Chapter 1: Introduction A. Purpose of Plan B. Central Baltimore Partnership C. Homewood Community Partners Initiative D. Progress To Date E. Why a New Plan F. Making Equity Front and Center G. Planning Process: 1. Front and Center Plan Goal 2. Phase 1: Understanding Existing Conditions 3. Phase 2: Preliminary Recommendations 4. Phase 3: Finalizing the Front and Center Plan Chapter 2: Planning Context H. Central Baltimore History I. Existing Conditions Chapter 3: Recommendations and Implementation Plan J. Recommendations • Social Fabric: Youth and Families • Economic Mobility: Workforce Development and Opportunities • Community Health: Physical and Mental Health, Safety, Public Space • Housing Access: Preserving Affordability, Improving Quality, Expanding Choices 2 CREDITS Planning Team: Keswick Multi-Care Center Joe McNeely, Planning Consultant Lovely Lane United Methodist Church Neighborhood Design Center, Design Consultant Maryland Bay Construction Maryland New Directions Planning Partners: Mosaic Community Services, Inc. 29th Street Community Center Open Works AHC, Inc. Greater Baltimore - Workforce Program People’s Homesteading Group Annie E. Casey Foundation Strong City Baltimore Association of Baltimore Area Grantmakers Telesis Baltimore Corporation (ABAG) Wells Fargo Regional Foundation Baltimore City Department of Housing and Community Development Data Work Group Members: Baltimore City Department of Planning Assistant Commissioner, Maryland -

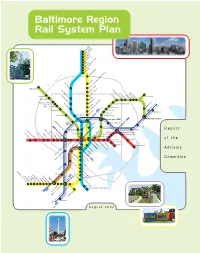

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

The Guy's Guide to Baltimore

The Guy's Guide to Baltimore 101 Ways To Be A True Baltimorean! By Christina Breda Antoniades. Edited by Ken Iglehart. Let’s assume, for argument’s sake, that you’ve mastered the Baltimore lexicon. You know that “far trucks” put out “fars” and that a “bulled aig” is something you eat. You know the best places to park for O’s games, where the speed traps are on I-83, and which streets have synchronized traffic lights. You know how to shell a steamed crab. You never, EVER attempt to go downy ocean on a Friday evening in the dead of summer. And, let’s face it, you get a little upset when your friends from D.C. call you a Baltimoro… well, you know. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Do you really know all it takes to be a true Baltimorean? ¶ Here, we’ve compiled a list of the 101 activities, quirky habits, and oddball pastimes, that, even if you only did half of them, would earn you certification as a true Baltimorean. Some have stood the test of time, some are new favorites, but all are unique to Charm City. If you’re a grizzled native, you’ll probably find our list a fun test that takes you down memory lane. And if you’re new in town, the guide below will definitely help you to pass yourself off as a local. ¶ So, whether you’ve been here 60 days or 60 years, we’re sure you’ll find something new (or long forgotten) in the pages that follow. -

B E C K E R B R O T H E

11 E. Mt. Royal Ave and 7 E. Preston St, Baltimore, MD 21201 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SALE OPPORTUNITY 11 E. MT. ROYAL AVE AND 7 E. PRESTON ST BALTIMORE, MD 21201 36,500+/- GROSS SQUARE FOOT RECENTLY REDEVELOPED OFFICE AND RETAIL BUILDING WITH ELEVATOR AND 37 PARKING SPACES BYRNES & ASSOCIATES, INC. 11 E. Mt. Royal Ave and 7 E. Preston St, Baltimore, MD 21201 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY: Built in 1920, 11 E Mount Royal Avenue previously served as a Zell Motor Car Company showroom and dealership. Today, the building is being Redeveloped and is offering ground level Retail units, traditional Office suites, 22 Coworking office suites, and a Penthouse office suite with a rooftop deck that offers sweeping city views. Modern renovations will showcase the elegant historic features of this downtown Baltimore landmark. 11 E Mount Royal is located on the bustling Mount Royal Ave just minutes from Penn Station, The University of Baltimore and across the street from The John and Frances Angelos Law Center. The building is situated in the Mt. Vernon Cultural District, a neighborhood widely considered as the Cultural and Arts epicenter in Baltimore City. Mt. Vernon is one of Baltimore's oldest and well-preserved neighborhoods and is designated as a National Historic Landmark District. Major employers in the neighborhood include: Chase Brexton Health Services, the University of Baltimore, and Agora Inc. Mt. Vernon’s central location in Baltimore City, as well as accessibility to public transportation and main city thoroughfares, makes it easily accessible to Downtown Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University, Johns Hopkins Hospital, and the suburbs of Baltimore City. -

Second Place 2010 Abell Award in Urban Policy

Second Place 2010 Abell Award in Urban Policy MARYLAND ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICTS: A PROCESS EVALUATION AND CASE STUDY OF BALTIMORE Cailin McGough Paul Messino Johns Hopkins University Institute for Policy Studies Masters in Public Policy Program The Abell Award in Urban Policy is presented annually to the student who writes the most compelling paper on a pressing problem facing the City of Baltimore and feasible strategies for addressing it. This award is co-sponsored by The Abell Foundation and the Johns Hopkins Institute for Policy Studies. Acknowledgments This research grew from the prior analysis we conducted as part of the 2008 Fall Baltimore Policy Project at John Hopkins University’s Institute for Policy Studies. We gathered subsequent interviews, observation and research for this paper through May 2010. We would like to thank Dr. Sandra Newman for the impetus to investigate the revitalization taking place in Station North and for her continued support. In addition, Dr. Curtis Ventriss provided insight that guided our research and Bonnie Wittstadt of John Hopkins University’s Milton S. Eisenhower Library aided us in the creation of A&E district maps. We would also like to thank David Bielenberg of Station North Arts and Entertainment Inc., Chris Ryer and Hillary Chester of Southeast Community Development Corporation, and all of the artists, residents, business owners and other stakeholders in Baltimore’s A&E districts who contributed to this report. Pamela Dunne of the Maryland State Arts Council and Jesse Rye of the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies provided valuable background information. We want to emphasize that this analysis is not meant to evaluate the program's impact or assess district "success." Rather, our scope is limited to the design of tax credits and the extent to which they are being used, with findings based on available data and interviews focusing on Baltimore's districts. -

Ronnie Kroell Time,” Paul Liller, the GLCCB’S De- Velopment Associate, Told Outloud

May 08, 2009 | Volume VII, Issue 10 | LGBT Life in Maryland Pride 2009 Off and Running An By Steve Charing With the recent crowning of King and Queen of Pride (see inside), Interview Baltimore Pride is off and running and is on target for another fun-filled celebration that officially takes place with the weekend of June 20-21. It rep- resents the 34th time that the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Super- Community Center of Baltimore and Central Maryland (GLCCB) has run the annual event in Baltimore. model “Pride has evolved from an ac- tivist event to one where the commu- nity can celebrate and have a good Ronnie Kroell time,” Paul Liller, the GLCCB’s De- velopment Associate, told OUTloud. This is Liller’s first year as the official Pride coordinator, but he has done By Josh Aterovis similar work as a volunteer in previ- ous years’ Pride celebrations. Ronnie Kroell is more than just a Where at one time Baltimore’s pretty face. He’s best known for Pride was confined to either one day appearing on the first season of or two days in June, over the past Bravo’s Make Me A Supermod- several years, the celebration be- el, where his cuddly bromance gan earlier with a series of events with fellow model and straight that lead up to the big day. Following friend, Ben, sent gay viewers the King and Queen of Pride Pag- — and many women, too — into eant held on April 24, a succession convulsions of ecstasy. They of other pre-Pride events has been even got one of those sickening- scheduled. -

Baltimore Regional Housing Partnership

Baltimore Regional Housing Partnership BALTIMORE Gans, Gans & Associates 7445 Quail Meadow Road, Plant City, FL 33565 813-986-4441 www.gansgans.com The Baltimore Regional Housing Partnership seeks an innovative, energetic, experienced, and passionate individual to serve as Executive Director. BRHP manages one of the nation’s most successful housing mobility programs, which has improved the quality of life for over 3,800 families using Housing Choice Vouchers. Created as a result of the civil rights case Thompson v. HUD, BRHP provides access to housing in opportunity areas across Central Maryland. These housing opportunities open educational and economic pathways to a better future for disadvantaged families and compensate for the legacy of housing segregation in public and assisted housing. In 2018, BRHP will assist several hundred families to move to communities of opportunity, and it will continue to serve at least 4,400 families thereafter. Under contract with the Housing Authority of Baltimore City, BRHP has an annual budget of approximately $70 million and employs 50 full-time staff. In addition to using Housing Choice Vouchers to expand housing opportunities, BRHP has used capital grants, worked for housing authorities, and has pursued other innovative strategies to improve the market for mobility. As a result of BRHP’s success, the organization has a responsibility not only to expand and enhance housing choices in Maryland but also to advocate for housing mobility and advise agencies throughout the country on how to provide quality, affordable, accessible housing outside areas of concentrated poverty. BRHP seeks an Executive Director who can continue the high-quality services it currently offers and also contribute to and implement a strategic vision to expand BRHP’s impact locally and nationally. -

About Baltimore—Charm City

Baltimore, Maryland - Charm City, USA Baltimore is the principal city and port of entry of Maryland and is the 13th largest city in the US, with a metropolitan area population in excess of 2.5 million. More than 100,000 students live in the Baltimore metropolitan area. Baltimore was named for the first Lord Baltimore, George Calvert, who was granted a charter key by King Charles in 1632 to establish an English colony in the New World. The first settlement on the site was made in 1662, and the town of Baltimore was laid out in 1730. The city owes its existence to the natural, deep- water harbor formed where the Patapsco River empties into the mammoth Chesapeake Bay. From its 1730 founding to the present, Baltimore has been a vital shipbuilding center and one of the nation’s largest commercial ports. Baltimore is centrally located and is only 40 miles away from Washington D.C., 70 miles away from Philadelphia, and is about 180 miles away from the New York City. By Maryland’s MARC train it costs about $5 and takes less than an hour to reach Washington, D.C. and by Amtrak train it costs about $60 and takes about 2.5 hours to Reach New York City. You can also reach New York by Greyhound bus for $25-35 (about 4-hour trip). Baltimore–Washington International Airport is one of the biggest and busiest airports in the nation and is a hub for US Airways, Southwest and United Airlines. One can catch a direct flight from Baltimore to almost any major city in America. -

Curriculum Vitae 2003-2019

CURRICULUM VITAE 2003-2019 TIMOTHY NOHE EDUCATION: MFA 1996 University of California, San Diego, Visual Arts, terminal degree, studies with George Lewis, Jerome Rothenberg, Sheldon Brown, Phel Steinmetz BFA 1989 Maryland Institute, College of Art, Photography CREATIVE WORKS: MUSICAL COMPOSITIONS: 2019 Space Structure, Baltimore Dance Project, choreography by Carol Hess. Physical modelling synthesis, percussion, ebow guitar performed and recorded by Nohe, live trombone by Sarah Manley. Presented at the SPARK Gallery at Light City, Columbus Center, Baltimore, November 10. In To and Out Of, dance score, choreography by Ann Sofie Clemmensen, work selected as part of the 2019 Local Dance Commissioning Project, REACH expansion of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, performed October 18 and 19. Physical modelling synthesis, percussion, ebow guitar performed and recorded by Nohe, reproduced on 4 Bluetooth speakers, in the round in the Welcome Pavilion. Tours to SPARK Gallery at Light City, Columbus Center, Baltimore, November 10. Biosphere, LucidBeings Dance, choreography Jeanna Riscigno and Franki Graham, presented at Maryland Council for Dance Professional Artists' Concert, Kraushaar Auditoritum- Goucher College. Dance score performed by Nohe on percussion, modular synthesizer, guitar, mezzo soprano voice by Dharna Noor, October 12. ART/SOUND/NOW, The Walters Art Museum, music commissioned by curator Alexander Jarman, electro-acoustic event for two sopranos and Bluetooth speakers. Physical modelling synthesis, percussion, ebow guitar performed and recorded by Nohe, August 22. The Edge Effect, evening length work in 7 movements, LucidBeings Dance, UMBC Dance Cube, April 28. Choreographers Frank Graham and Jeanna Roscigno. Nohe sequencing, synthesizers, field recordings, Dharna Noor and Bonnie Lander, sopranos, and James David Young, bassoon. -

Look Around Because Fine Film Abou-Nds Baltimore's Diverse

PAGE 18 THE RETRIEVER WEEKLY FOCUS APRIL 4, 2000 Baltimore's Diverse push some boundaries artisti memory lane. Remember cally; they aren't films manipu when you were a child and you lated by major motion picture Contribution to Cinema watched the Pee Wee Herman companies, and they're usual LEANNE CURTIN AND NICK BECKER naming February 7, 1985 John Waters Day. show, when you adored Pee ly created by unknowns. Retriever Weekly Staff Edith Massey, one of the regulars in Wee before he got caught These days, unknowns are Waters' early films, best know as the Egg playing with his pee wee? He being pushed to the forefront What do transvestites, UMBC, spiders Lady, owned a thrift store in Fells Point. ran a segment with a Word of of pop culture and becoming and Dom Delouise have in common? No, It's still open, now called Flashback, at 728 the Day theme. Well, today's "somebodys." This is valuable they're not from the lyrics of an Eddie S. Broadway, run by Bob Adams (Ernie word, kiddies, is "indie." lndie because it gives society Money song; they are all related to famous from Female Trouble). John Waters still seems to be the new catch access to new, creative ideas and not-so-famous local filmmakers. lives in Baltimore to this day; you can spot phrase to describe under and scripts. A lot of indie films First and most important of all, John him at local haunts such as the Ottobar and ground, edgy and cool. It's a out there are really horrid, but Waters hails from Baltimore, delights even attending UMBC drama productions.