Front and Center: a 5-Year Equity Plan for Central Baltimore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Profile for the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Theatre

Khamar Hopkins Sunday, February 24, 2019 AAD 612 - Marketing and the Arts Michael Crowley Community Profile for The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Theatre The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Theatre, or better known as the Parkway, is a historic theatre located in the heart of Baltimore’s Station North Arts and Entertainment District that recently reopened its doors in the spring of 2017. The Parkway first opened its doors on October 23rd, 1915, with the feature premiere of Zaza, directed by Hugh Ford and Edwin S. Porter, and starring Pauline Fredrick.i During its first decade the Parkway would screen Paramount movies, had an orchestra, an organ, a cameraman, and could seat up to 1100 patrons. In 1926 the theatre was purchased and remodeled by Loews Incorporated, also known as Loew’s Cineplex Entertainment Corporation (as of January 26, 2006, Loews was acquired by AMC Entertainment Inc.)ii and 2 years later it got rid of its orchestra for Vitaphone and Movietone sound systems, and could now only seat 950 customers. The theatre would continue to function as a Loews theatre until it closed during the summer of 1952. With its next owner, Morris Mechanic, the Parkway had a short-lived season as a live theatre before it closed again. On May 24th, 1956, the Parkway reopened under the new name, 5 West, with the premiere of Ladykillers, and started rebranding itself as an art-house cinema. The new 5 West cinema could only hold 435 guests and provided great entertainment to the local community along with its neighboring theatres, but it started to struggle in the late 1970’s and then closed its doors again in the winter of 1978. -

SG the Fitzgerald Brochure New.Indd

FOR LEASE Maryland DC • Virginia Online 605 South Eden Street, Ste 200 1600 Wilson Boulevard, Ste 930 www.segallgroup.com Baltimore, MD 21231 Arlington, VA 22209 Member of 410.753.3000 202.833.3830 Where the Midtown neighborhoods of Mt Vernon, Station North and Bolton The Opportunity Hill meet, you will fi nd The Fitzgerald. Inspired by F. Scott Fitzgerald and Approximately 19,000 square feet of prime space is available on the energy of his era, this Baltimore development offers more than just two levels – 14,359 on the ground fl oor and 5,069 square feet on a somewhere to hang your hat. The developer, Bozzuto Group, blended Mezzanine level open to the fl oor below. These two areas are currently connected by elevator and escalator and, due to Oliver Street’s rising stunning features with fantastic amenities in a culturally rich environment. slope, both at street grade. Entertainment, grocery or fi tness uses are Sandwiched between the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) and the sought for the larger portion or the entirety, while the smaller area can University of Baltimore, The Fitzgerald is a mixed use project consisting of be demised for a café that caters to this culturally rich party of the City. almost 25,000 square feet of dynamic urban retail space, 275 residential units and a 1,250 space parking garage that serves University of Baltimore Quick Facts students as well as area visitors. The project’s retail component is ideal for LLocationocation Retail space in Luxury Apartment Building entertainment, service, retail and restaurant uses to serve students and faculty, 19,428 square feet SSizeize neighborhood residents, out of town visitors, local offi ce workers and patrons (14,359 lower level and 5,069 Mezzanine) of the great local entertainment and cultural venues including the Lyric Opera DDeliveryelivery Immediate House & Theater, The Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, and the Parkway, Centre and RRentalental RRateate Negotiable Charles Theatres in the nearby “Station North” Arts District. -

Before the Washington, DC 20554 See Petition of the California Public

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of Petition of the California Public Utilities CC Docket No. 99-200 Commission for Delegated Authority to Implement Specialized Transitional Overlays VERIZON’S’ COMMENTS SUPPORTING PETITIONS FOR RECONSIDERATION OF THE COMMISSION’S SEPTEMBER 9,2005 ORDER PERMITTING CALIFORNIA TO IMPLEMENT A SPECIALIZED OVERLAY The Federal Communications Commission (“Commission”) should grant the petitions for reconsideration filed by Pac-West Telecomm, Inc. (“Pac-West”)* and the California Cable & Telecommunications Association (“CCTA”).3 The specialized overlay plan proposed by the California Public Utilities Commission (“California PUP) is unworkable, would impede local number portability, and would waste, rather than preserve, valuable numbering resources. The Commission should therefore reconsider and withdraw its Order4 permitting the California PUC to implement specialized overlays in California. 1 The Verizon telephone companies (“Verizon”) are the companies affiliated with Verizon Communications Inc. that are listed in Attachment A. 2 Petition for Reconsideration of Pac-West Telecomm, Inc., CC Docket No. 99-200 (filed Oct. 11,2005) (“Pac- West Petition”). 3 Petition of the California Cable & Telecommunications Association for Reconsideration, CC Docket No. 99-200 (filed Oct. 11, 2005) (“CCTA Petition”). 4 See Petition of the California Public Utilities Commissionfor Delegated Authority to Zmplement Specialized Transitional Overlays, 20 FCC Rcd 14624 (2005) (“Order”). -

Exhibit 1.0 (Smith)

STATE OF ILLINOIS ILLINOIS COMMERCE COMMISSION NANPA, on behalf of the Illinois ) Telecommunications Industry ) ) Docket No. 00-0677 Petition for Approval of Numbering Plan ) Area Relief Planning for the 618 Area Code ) DIRECT TESTIMONY OF DANA SMITH ON BEHALF OF VERIZON WIRELESS January 15, 2002 Verizon Wireless Testimony Docket No. 00-0677 Exhibit 1.0 (Smith) 1 Introduction 2 Please state your name and business address. 3 A. My name is Dana Smith and my business address is Six Campus Circle, Westlake, Texas 4 76262. 5 Q. By whom are you employed and in what capacity? 6 A. I am employed by Verizon Wireless (“VZW”) as a Member of the Technical Staff in the 7 Numbering Policy and Standards group within VZW’s Network Planning Organization. 8 Q. Please summarize your education and work experience. 9 A. I received a Bachelor’s of Business Administration degree from the University of North 10 Texas in Denton, Texas in 1992. I have been employed with Verizon Wireless and its 11 predecessor companies since 1995, holding several positions within the Network 12 organization. I have worked exclusively on numbering issues for the past four years, 13 supporting fifteen states in the South and Midwest. My responsibilities have included 14 code administration, area code relief planning and implementation, and representing the 15 company’s interests at several national forums, including the Industry Numbering 16 Committee. 17 Q. Have you previously testified before this Commission? 18 A. Although I have not testified before this Commission, I have testified before other state 19 commissions as an expert on numbering issues. -

Artists Are a Tool for Gentrification’: Maintaining Artists and Creative Production in Arts Districts

International Journal of Cultural Policy ISSN: 1028-6632 (Print) 1477-2833 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gcul20 ‘Artists are a tool for gentrification’: maintaining artists and creative production in arts districts Meghan Ashlin Rich To cite this article: Meghan Ashlin Rich (2017): ‘Artists are a tool for gentrification’: maintaining artists and creative production in arts districts, International Journal of Cultural Policy, DOI: 10.1080/10286632.2017.1372754 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2017.1372754 Published online: 06 Sep 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 263 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gcul20 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CULTURAL POLICY, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2017.1372754 ‘Artists are a tool for gentrification’: maintaining artists and creative production in arts districts Meghan Ashlin Rich Department of Sociology/Criminal Justice, University of Scranton, Scranton, PA, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This study investigates the relationship between arts-themed development Received 7 June 2017 and the strategies used by neighborhood stakeholders, including artists Accepted 16 August 2017 and other marginalized populations, to maintain their place in gentrifying KEYWORDS arts and cultural districts. Using a case study of a state-sanctioned Arts & Artist communities; creative Entertainment District in Baltimore, MD (U.S.A.), I find that the organizations placemaking; gentrification; that are ‘thoughtful’ in their development actively seek to maintain the urban planning and policy production of arts and the residency of artists in the neighborhood into perpetuity. -

Upcoming Community Events Fall 2017 As of October 19, 2017

Upcoming Community Events Fall 2017 As of October 19, 2017 Community Education/Awareness Immunizations Program Tuesday 9:30 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. BCHD Eastern Health District 620 N. Caroline Street Baltimore, Maryland 21205 Wednesday 10:00 a.m. – 2:00 p.m. BCHD Immunization Office 1800 N. Charles Street, Suite 600 Baltimore, Maryland 21201 Thursday 9:30 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. Eastern Health District 620 N. Caroline Street Baltimore, Maryland 21205 A Healthy Approach to Your Career - (Guest Speaker) Weekly on Tuesday (subject to schedule change based on class size) 11:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. America Works of Maryland 22 Light Street, 5th Floor Baltimore, Maryland 21202 Line Dance for A Cause (Breast Cancer Awareness Event) October 21, 2017 1:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. Glenarden Community Center 8615 McLain Avenue Glenarden, MD 20706 Annual Forest Park Senior Center Health & Wellness Fair October 24, 2017 10:00 a.m. – 3:00 p.m. Forest Park Senior Center 4801 Liberty Heights Avenue Baltimore, Maryland 21207 Mayor Catherine Pugh's Fall Festival and Winter Coat Giveaway October 27, 2017 4:00 a.m. – 7:00 p.m. War Memorial Plaza N. Holiday Street Baltimore, Maryland 21202 Re-Entry Expungement & Community Resources Fair October 28, 2017 10:00 a.m. – 3:00 p.m. Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Epsilon Omega Chapter 3515 Dolfield Avenue Baltimore, Maryland 21215 The Family Tree’s Brent A. Rosenberg FamFest (MedStar Health partnership) October 28, 2017 12:30 p.m. – 3:30 p.m. Weinberg Y in Waverly on 33rd Street East 33rd Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218 "The Hip-Hope Festival" October 28, 2017 12:00 p.m. -

Resource-Inventory-Cbsa-Jhh-Jhbmc.Pdf

Using the zip codes which define the Johns Hopkins Institutions community (21202, 21205, 21206, 21213, 21218, 21219, 21222, 21224, and 21231) more than 400 community resources were identified with the capacity to meet the community health needs identified in the Johns Hopkins Institutions CHNA. (Please refer to the Community Health Needs Assessment Report to review the detailed community needs.) Note: The astericks in the columns represent the top priority areas that were identified. They include: improving socioeconomic factors, access to livable environments, access to behavioral health services, and access to health services. An "x" in the columns are subcategories that further illustrate the identified need. INVENTORY OF COMMUNITY RESOURCES AVAILABLE TO ADDRESS COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS IDENTIFIED IN THE JOHNS HOPKINS CHNA Internet Organization/Provider Column1 Counties Served Contact Information Zip Code Information Population Served Services Provided IMPROVING SOCIOECONOMIC FACTORS Education Employment ACCESS TO LIVABLE ENVIRONMENTS Housing Food Environment Crime and Safety ACCESS TO BEHAVIORAL Mental Health Substance Abuse ACCESS TO HEALTH SERVICES Dental Services Uninsured Chronic Disease 2‐1‐1 MARYLAND AT UNITED WAY OF CENTRAL MARYLAND ADDED 4/18/16 Baltimore, 100 South Charles St., 5th Floor 21203 More Information No Restrictions 2‐1‐1 Maryland is partnership of four agencies working together to provide simple access to Baltimore City Bank of America Center health and human services information. 2‐1‐1 is an easy to remember telephone number that Baltimore, MD 21203 connects people with important community services. Our specially trained call specialists answer Phone: 443‐573‐5908 calls 24 hours a day, every day of the year. -

Baltimore New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 2Q20

Baltimore New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 2Q20 51 47 112 113 102 114 111 49 101 110 48 16 116 52 117 115 109 6 98 53 11 54 103 12 50 ID PROPERTY UNITS 52 East of Market Phase II 50 100 1 The Wexley at 100 392 53 Hamilton Station 80 6 The View at Mill Run Phase II 157 54 Meadow Road & Old National Pike 600 Total Lease Up 549 Total Planned 1,807 99 94 105 95 11 Avalon Foundry Row 437 108 45 94 47 West Avenue 173 104 12 The Warfield at Historic Sykesville 180 95 Lyon Homes Phase II 90 107 106 46 1 13 The Refinery 250 98 Village of Cross Keys 318 16 Riverwoods at Tollgate Phase II 57 13 99 Promenade 250 Total Under Construction 924 100 Johnnycake Road 318 101 Hunt Valley Towne Center Redevelopment 500 43 Lofts at Eastport Landing 98 102 Timonium Square 100 44 Newtowne 86 103 The Enclave at Lyons Mill 54 111 Bel Air Overlook 201 45 Ellicott Gardens Phase II 70 104 Riverwatch Phase II 58 112 Crossroads at Hickory 184 46 Long Reach Village Center 252 105 Dorsey Overlook 133 113 830-858 Gilbert Road 322 47 Harbour Hills 60 106 Artist Flats 53 114 Residences at Greenway Farms Phase II & III 480 48 James Run Project 300 107 Clarksville Commons Phase II 100 115 Catoctin Manor Redevelopment 76 49 Village at Blenheim Run 51 108 Downtown Columbia Lakefront Core 509 116 Free and Medwid 100 50 Mount Airy Senior 60 43 109 New Hope Commons 50 117 Sycamore Ridge 124 44 51 Taneytown Crossing 100 110 Aumar Village Residential Subdivision 86 Total Prospective 4,279 5 mi Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up Under Construction Planned Prospective -

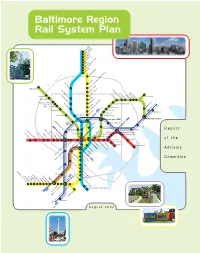

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

Approval of a Relief Plan for the 2?0 Area Code ("270 NPA"). Neustar Functions As The

COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY BEFORE THE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION In the Matter of: APPLICATION OF THE NORTH AMERICAN ) NUMBERING PLAN ADMINISTRATOR, ON ) ADMINISTRATIVE BEHALF OF THE KENTUCKY ) CASE NO. TELECOMMUNICATIONS INDUSTRY, FOR ) 2012-00129 RELIEF OF THE 270 NUMBERING PLAN AREA ) ORDER On April 2, 2012, Neustar, lnc. ("Neustar") submitted to the Commission an application on behalf of the Kentucky telecommunications industry ("Industry" ) for approval of a relief plan for the 2?0 Area Code ("270 NPA"). Neustar functions as the North American Numbering Plan Administrator ("NANPA") pursuant to a contract with the Federal Communications Commission ("FCC"), which has ultimate authority over the North American Numbering Plan. In its filing with the Commission, NANPA estimated that the supply of Central Office ("CO") prefixes available within the 270 NPA would be exhausted by the first quarter of 2015." The application filed by NANPA reflected Industry's consensus decision to recommend an alt-services distributed overlay plan as its preferred method of relief for the 270 area code. Thus, on August 30, 2012, the Commission opened this administrative case to develop a 270 NPA relief plan. Since the filing of its application, NANPA released the October 2012 Numbering Resource Utilization Forecast, which now estimates that the 270 NPA will be exhausted during the first quarter of 2014. BACKGROUND NANPA first submitted an application for relief of the 270 NPA on July 25, 2001.'umbering conservation measures taken by the FCC and the Commission, along with reduced historical and projected demand for numbering resources by industry members, contributed to extending the projected exhaust date, which led to the Commission's closing of the matter. -

Baltimore City Arts & Entertainment District Report

B A LTIMORE’ S A R T S & ENT E R TAINMEN T DIS TRIC T S W ORKIN G G R OUP REP O R T MARCH 2015 BALTIMORE’S ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICTS WORKING GROUP REPORT MARCH 2015 MEMBERS CONTENTS City of Baltimore 02 Casey Brent, Special Assistant, Mayor’s Office - Economic Executive Summary and Neighborhood Development Laura Larsen, Budget Management Analyst I 04 Dan Taylor, Central Team Director, Baltimore Develop- I. Introduction ment Corporation 06 Maryland State Arts Council II. Background Pamela Dunne, Program Director, Arts & Entertainment Districts 08 III. The State of Baltimore’s A&E Districts Baltimore Office of Promotion & the Arts Bill Gilmore, Executive Director 18 Krista D. Green, Cultural Affairs Assistant Director IV. Moving Forward Bromo Tower Arts & Entertainment District Priya Bhayana, Director, Bromo Tower Arts & 21 Entertainment District Appendix A: A&E District Profiles Jim French, French Companies Jessica Lanzillotti, Everyman Theatre 29 Jeffrey Kent, Subbasement Studios Appendix B: Memorandum Highlandtown Arts & Entertainment District 32 Chris Ryer, Director, Southeast CDC Appendix C: A&E District Legislation Sandra Abbott, Acting Secretary of ha! Gina Caruso, Creative Alliance Margaret Footner, Creative Alliance Kari Snyder, Southeast CDC Station North Arts & Entertainment District Ben Stone, Executive Director, Station North Arts & Entertainment, Inc. Rebecca Chan, Program Director, Station North Arts & Entertainment, Inc. Jane Brown, Robert W. Deutsch Foundation Marian Glebes, Guppy Management, artist + curator Mike Molla, Maryland Institute College of Art EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Baltimore’s three designated Arts & Entertainment (A&E) Districts lead the city’s cultural renaissance and serve as a national model for cultural districts. The Bromo Tower, Highlandtown, and Station North Arts & Entertainment Districts produce outstanding art installations and performances, host international festivals, convene national conferences, and earn nationally competitive grants for creative placemaking and arts based community development. -

The Guy's Guide to Baltimore

The Guy's Guide to Baltimore 101 Ways To Be A True Baltimorean! By Christina Breda Antoniades. Edited by Ken Iglehart. Let’s assume, for argument’s sake, that you’ve mastered the Baltimore lexicon. You know that “far trucks” put out “fars” and that a “bulled aig” is something you eat. You know the best places to park for O’s games, where the speed traps are on I-83, and which streets have synchronized traffic lights. You know how to shell a steamed crab. You never, EVER attempt to go downy ocean on a Friday evening in the dead of summer. And, let’s face it, you get a little upset when your friends from D.C. call you a Baltimoro… well, you know. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Do you really know all it takes to be a true Baltimorean? ¶ Here, we’ve compiled a list of the 101 activities, quirky habits, and oddball pastimes, that, even if you only did half of them, would earn you certification as a true Baltimorean. Some have stood the test of time, some are new favorites, but all are unique to Charm City. If you’re a grizzled native, you’ll probably find our list a fun test that takes you down memory lane. And if you’re new in town, the guide below will definitely help you to pass yourself off as a local. ¶ So, whether you’ve been here 60 days or 60 years, we’re sure you’ll find something new (or long forgotten) in the pages that follow.